An interview with Conor Stechschulte

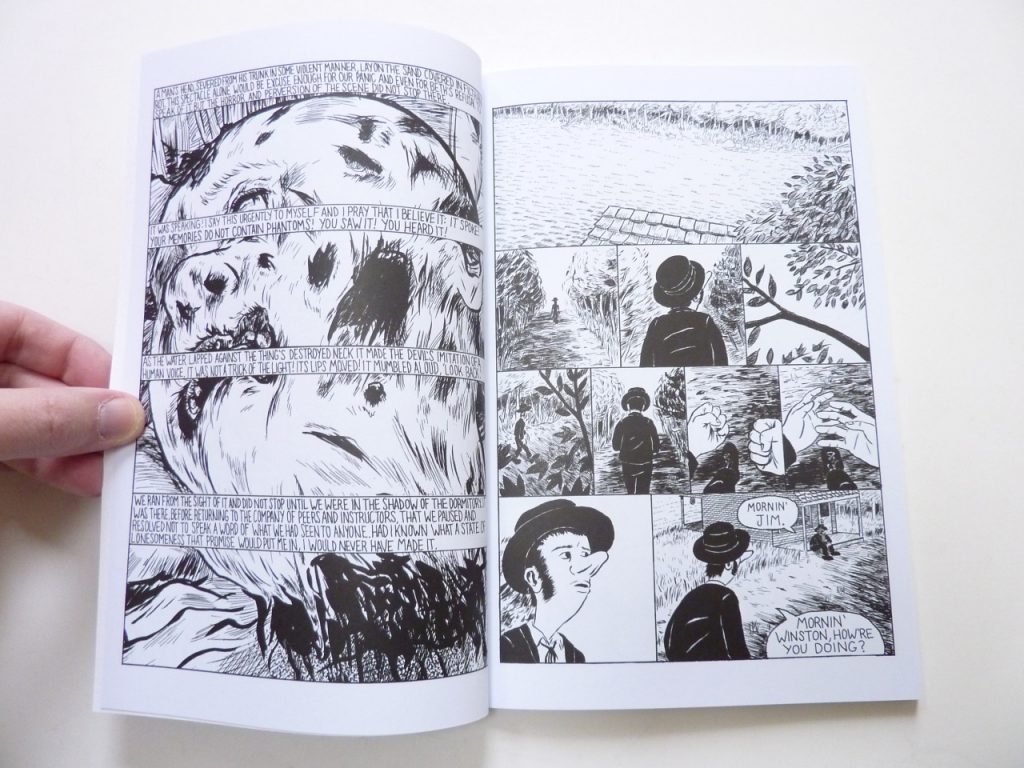

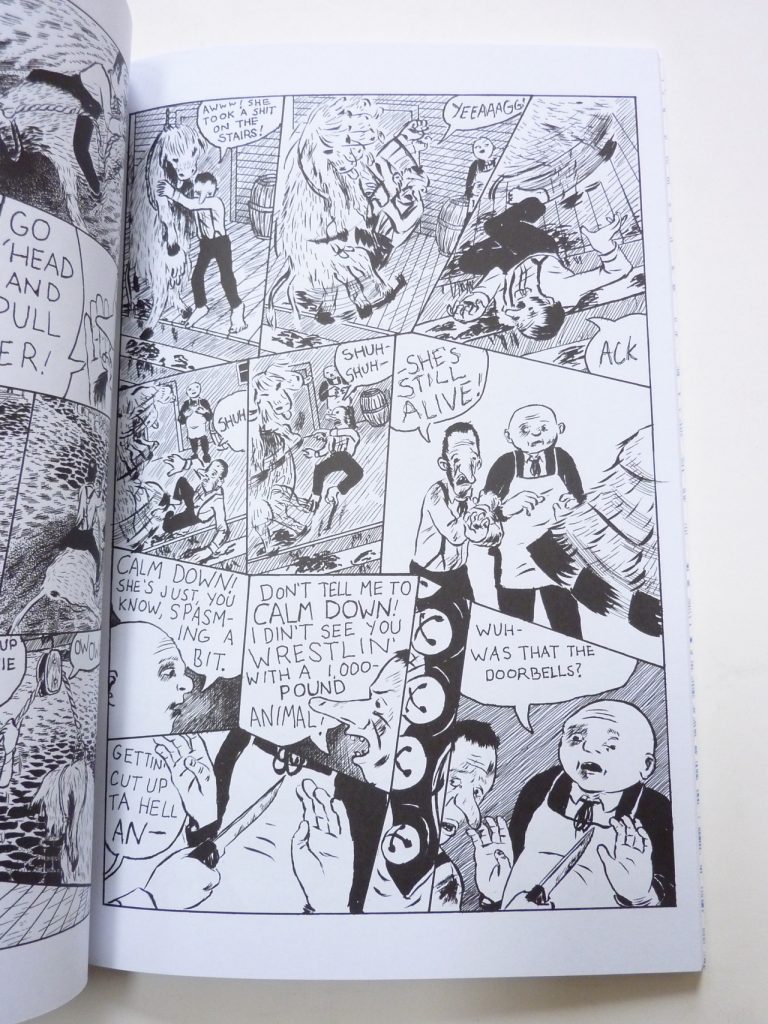

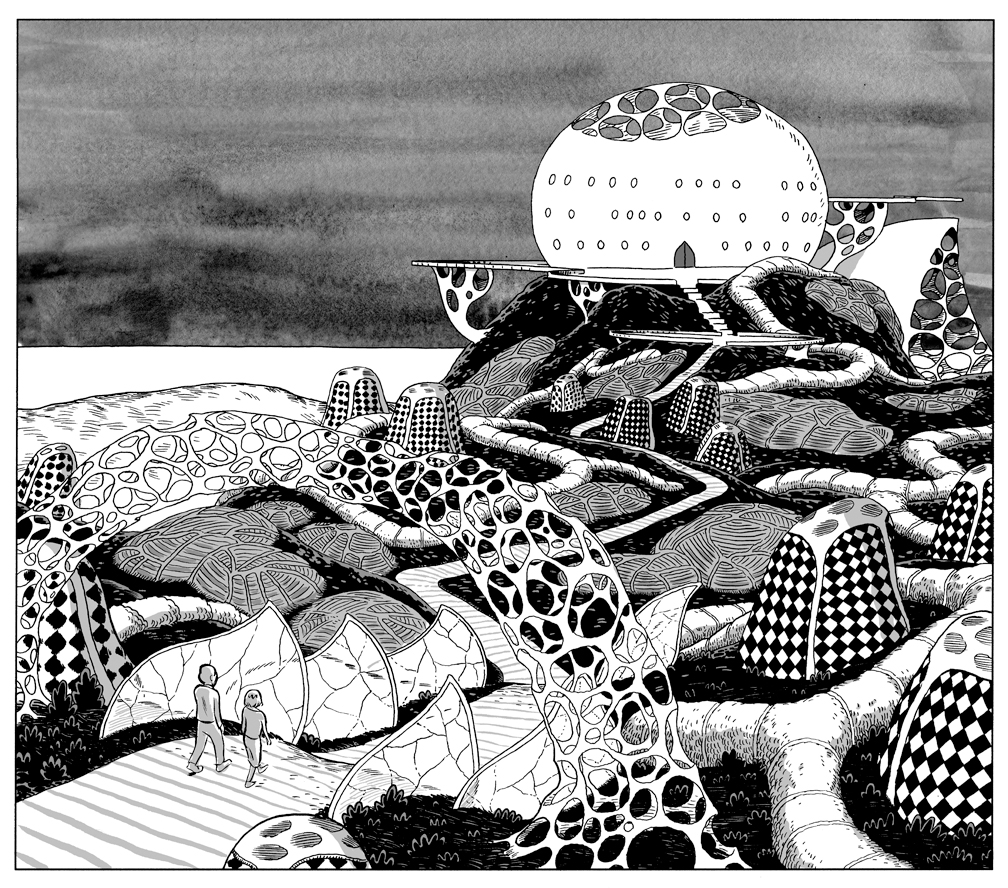

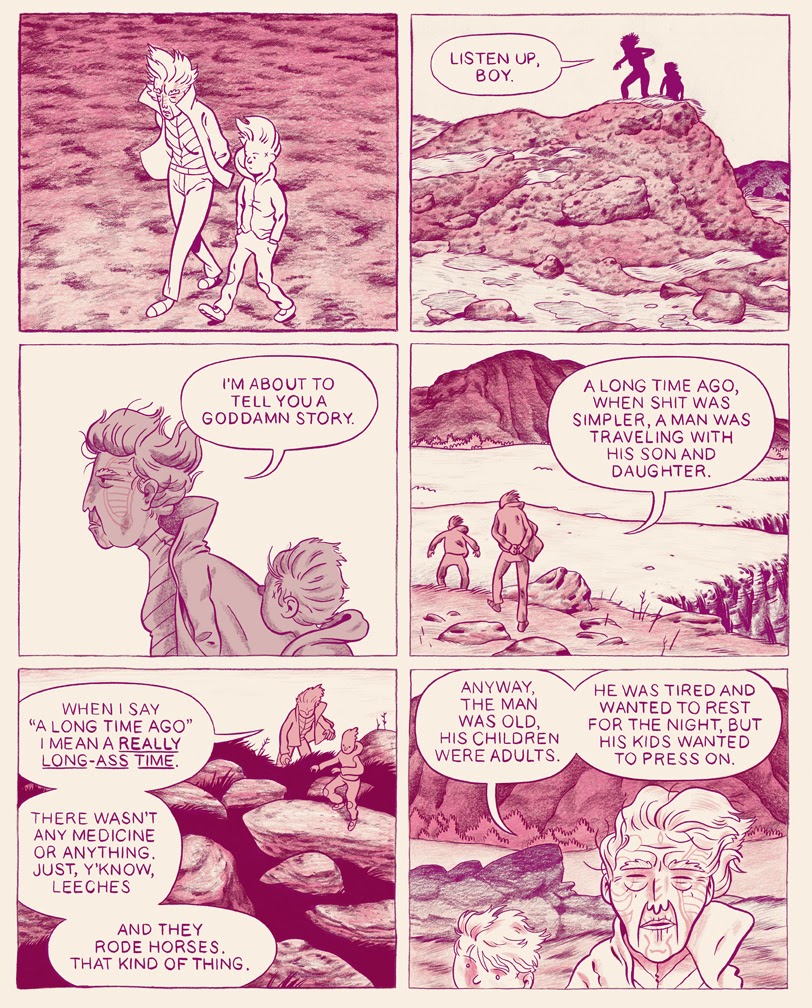

Conor Stechschulte is the author of The Amateurs, a graphic novel published by Fantagraphics in 2014, of Generous Bosom, a series for Breakdown Press now at its third installment, and of several self-published comics. Conor will be in Italy for BilBOlbul festival in Bologna, where he will have Il peso dell’acqua (The Weight of Water), an exhibition of his works open from 24th November until 20th December at the Spazio & gallery. And in the same days 001 Edizioni will publish I Dilettanti, the Italian translation of The Amateurs.

We asked some questions to Conor to introduce him to the Italian audience. The interview was conducted by e-mail between September and October 2017 by Gabriele Di Fazio, Elisabetta Mongardi and Alessio Trabacchini.

The Amateurs reflects your ability to introduce mystery in everyday life. The story seems to illustrate through the various characters (both in the main plot and in the frame) different ways to relate to the mysterious and non-rational aspect of existence. We don’t know if you agree with this interpretation, but we would like to begin this interview talking about your relationship with this element and how you think it can be communicated, displayed or evoked through art.

Fiction can help demonstrate ways to look sideways at what we’re experiencing. This is a great gift I’ve gotten from art and one I’m trying to pass on. Similarly, I really enjoy when I dream about something really banal – that I’ve moved a small object in my apartment or retrieved something from the car – and because it fits right in with reality, it’s like a weird boring time bomb that goes off with a light pop. It makes the rest of my day feel a little unreal. This just happened to me recently, I dreamt that I’d accidentally sent a bunch of pictures from my phone to a stranger and he’d replied simply, “Ha”. Several days after the dream I had a real moment of panic that this lightly embarrassing thing had actually occurred.

So, if dreams of objects from ordinary life are important for your art, it’s also true that the beginning of The Amateurs shows the opposite process, since something strange pops in everyday life. In fact the head found in the river kicks off a series of extraordinary events, as it happens with the severed ear found in the field at the beginning of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. Your comics reveal the permeability between dreams and reality, but can you tell us more about how dreaming experience goes into your work? And do you look at some artists in particular who have taken this road?

I’d really like to lucid dream, though so far I’ve not had any success with it except in the early-morning time between hitting “snooze” on the alarm. I’ve come up with a lot of solutions to story problems and images in this space (one I can recall for sure is the final image from The Dormitory of the guy smoking in the basement window).

An author that immediately springs to mind on this subject is Jesse Ball. I had the privilege of advising with Jesse during my last semester at the School of the Art Institute this past spring and I just read Sleep, Death’s Brother, his book on lucid dreaming. He has much more interesting and useful things to say about dreaming than I do but I am especially excited by his idea of the dream-space as a training ground for the will; his book on dreaming is in fact intended for children and incarcerated persons for the exercise of the will under restricted circumstances.

Most of my favorite authors and artists have “taken this road.” Kobo Abe is an important favorite of mine, I’m thinking a lot about his book Secret Rendezvous in the most recent volumes of Generous Bosom. In his journals, Werner Herzog makes no distinction between everyday events and dream imagery (though he claims not to dream at night). The originating idea for The Amateurs sprung from a scene I read in his journals where he describes inept butchers on the banks of a river in Iquitos. In comics, I think that Olivier Schrauwen is a master of dreamlike/fantasy/subjective points of view and playing with the humor of their discontinuity with outside reality. Other important books/authors/artists for me in this vein are J.G. Ballard’s Unlimited Dream Company, Solaris by Stanislaw Lem, The Journey to the East by Hermann Hesse, Wind up Bird Chronicles by Haruki Murakami, Borges of course, Philip K. Dick, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Tarkovsky, Lynch of course… And lots of others I’m forgetting.

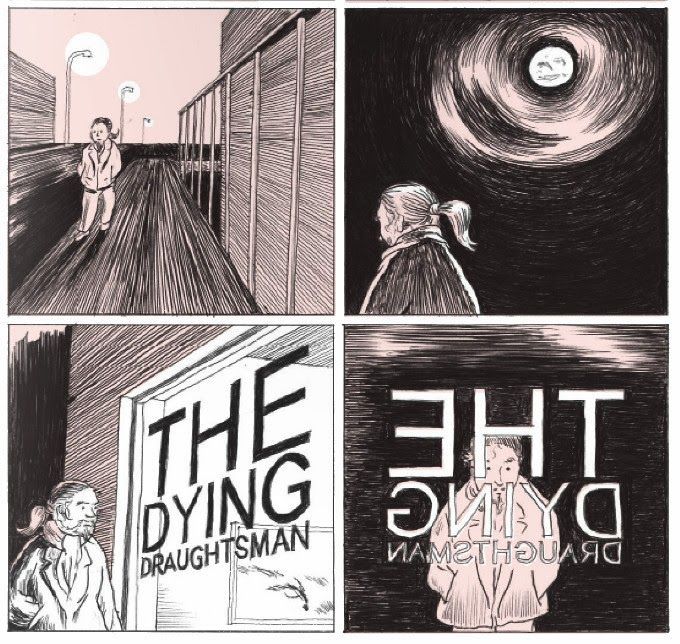

The Fantagraphics edition of The Amateurs shows some differences from the first version you self-published in 2011. The most significant is the replacement of the hand-written introduction with a completely new storyline about two schoolgirls finding a man’s head in the river, the same river where they will perform a graduation ritual along with their classmates. Why did you decide to revise the original comic and how did you create this other storyline?

It started with simple dissatisfaction with the letter visually. It was one of the last things I had added to the comic and the more I looked at it the more unconvinced I was. A couple months after I’d self-published the book, I had the idea for that second storyline and thought, “Well if I ever have the chance to reprint it, I’ll include that”. So when the opportunity came along with Fantagraphics, it was one of the first things I did.

Animals have a key role in The Amateurs, they look strong and aware, while Jim and Winston, the two butchers who are the main characters of the story, are weak and confused. This, and the use of brutal violence in some sequences where animals are considered only as food, seem to imply a condemnation of eating animal meat. It should be interesting to understand if you wanted to convey a sort of “message” or if the interpretation is more metaphorical.

I made Jim and Winston butchers because it’s a profession that deals intimately with death. I wanted to talk about how people, rather than reckoning with death, will externalize it and locate it in the body of another, this always leading to harm on both sides of the equation.

That said, at the time I made the book I’d been a vegetarian for twelve years. I’ve since starting eating meat again. Haha, not sure if that shines any kind of light on the content… If someone were to decide become vegetarian after reading the book, that’d be great.

While reading The Amateurs, the impression is that the gender of your characters is not randomly chosen. In addition to some obvious hints (the all-girls school, the two customers…), all the animals that at some point rebel against humans are female (the sow, the mare, the cow), while the male are somehow more subdued (the pig walks into the slaughter of its own accord; the turtle gets tortured in the woods). It also seems like whatever the sinister power of the river is, it doesn’t affect women: they bathe, wash their clothes and make rituals in it, and nothing seems to happen to them. On the other hand, when Winston and Jim go into the water, they get literally shredded. There is also a scene where Winston – right after he has grinded his own fingers – yells at the two customer, saying he won’t put up with a woman telling him his work is not good enough. Not to speak of the fact that he remembers the two customers dressing him up as a girl when they were all kids. It seems to me that your book is filled with subtle references to men-women relationships (or to the general opposition between masculinity and femininity). Was that intentional or we are overthinking it? And does the river have anything to do with the representation of femininity in your book?

Thank you for such a close reading. You’re absolutely right that, at least in terms of my intentions, gender was a primary thing I was trying to address.

At the risk of over-explaining and squeezing out better and more interesting interpretations, I’d say that The Amateurs is an attempt to lampoon, ridicule and take apart (literally, haha) the idea of self-reliant, non-relational masculinity – the man who has all the answers. This is the character that Jim and Winston try to perform for the women in the book.

A huge influence on The Amateurs was the book Flesh of my Flesh by Kaja Silverman. She argues for replacing the Oedipus myth with the Orpheus myth with regards to gender – a story based on mortality rather than castration. She says our mortality allows us to relate to one another analogously, through our resemblances rather than metaphorically which always presumes a hierarchy. I was trying for a lot of these ideas and borrowed imagery from the Orpheus myth (i.e. the head washed up on the shore).

Thank you for pointing out this pattern in the gender of the animals, I don’t think I consciously set that up. I think a similar sort of pattern is emerging in Generous Bosom as well, where the main character and “Hero” of the story is actually very passive.

As for the water, I think of the water as being representative of an ecstatic/transcendent/undefined state rather than being specifically gendered.

Water, of course… It is a recurring element in your comics, and sometimes plays a major role. It may be the ritual river in The Amateurs, the rain from which the facts of Generous Bosom develop, the lake of impalpable but sharp tensions in Glancing, the sea where the games of Water Phase unfold, and Christmas in Prison’s narrative stream. If we consider water as a symbol, it is necessarily multifaceted, fluid, and seems to be related to desire, change, epiphany. It is the place where things happen, stories are told, secrets come to light. Why is water so important to you?

Thank you for tracking this image so comprehensively throughout my work! You’ve done such a good job of outlining how I’ve used water that I’m not sure if I can add anything…

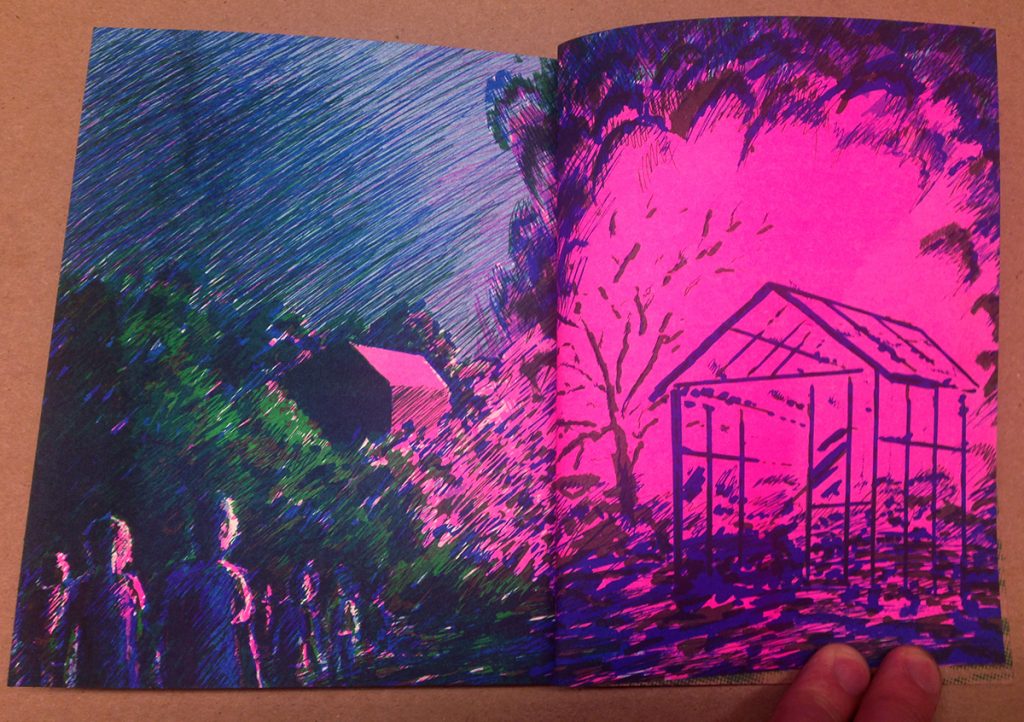

Of the symbolic meanings you’ve listed I identify most with the idea of change. Water is a place where boundaries break down, things dissolve, definitions shift.

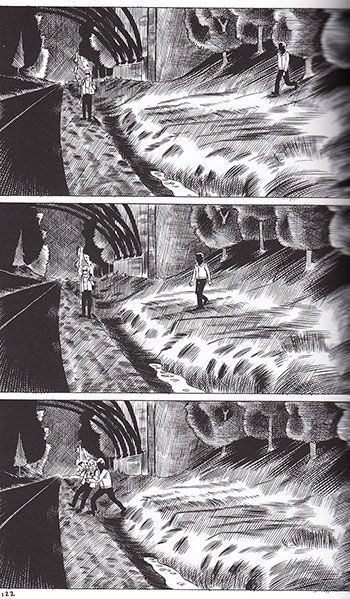

With how clear and declarative one must be in telling a story, especially with comics (here’s a guy, now here he is again, see? He’s wearing the same shoes and hat, except now he’s dropped his umbrella, and here he is again but now he’s bending to pick it up), water provides a needed space for vagueness. It’s a place where the closure occurring between each panel might be suspended (or maybe it’s a way of depicting that no-space in between). You can draw a clean, clear black-outlined character for most of your book but if you reflect the same character in a bowl of water, their lines go all wavy. They can be different.

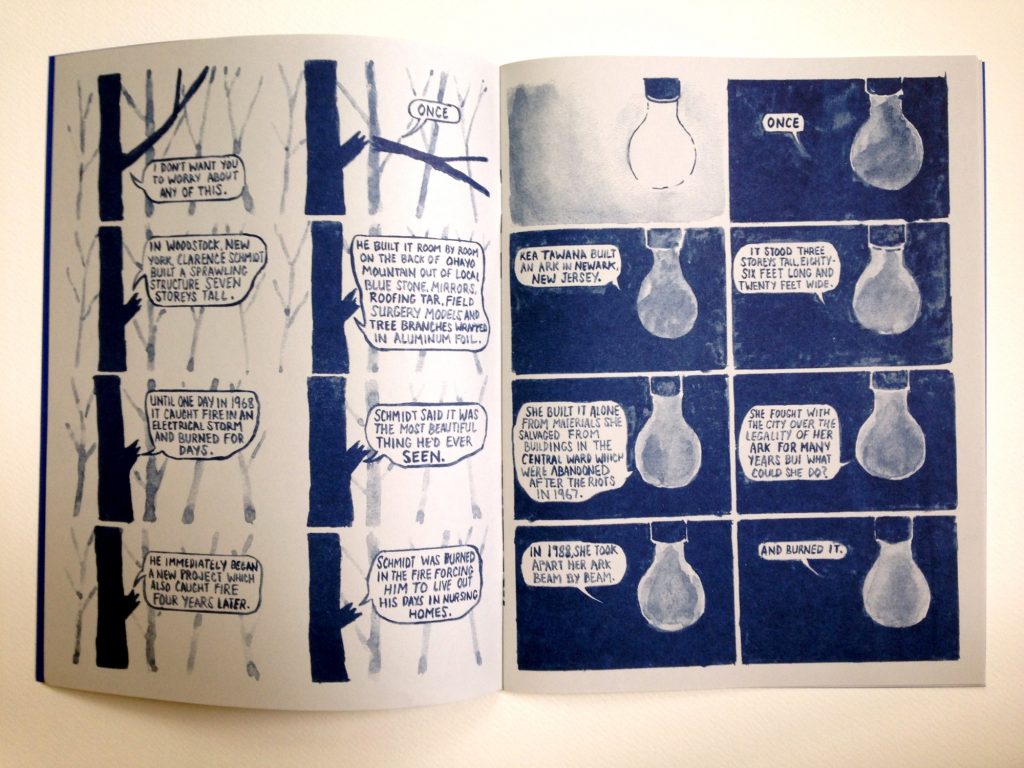

This confirms your are constantly looking for new ways of telling a story. For example another rule-breaking work is your most recent one, Tintering, where you didn’t draw characters but you told the story of five self-taught artists using different broken objects, with the single panels very similar to each other, while the content is mostly developed with text balloons. How did you come up with this, and why are you focusing your attention on objects?

The subject matter for the comic all came from an art history class I took which was taught by Lisa Stone, who is an incredible, generous, brilliant scholar on the subject of self-taught and vernacular artists. The way a lot of these artists related to objects was different from how we do (or must) in everyday life. Kea Tawana, for example, meticulously and respectfully took apart these old buildings in Newark. She had immense sensitivity to craftsmanship and couldn’t stand to see good materials go to waste. Much of the work of self-taught artists serves as a response to our culture’s massive generation, disregard and waste of objects.

I was originally thinking the comic might look like some of the stuff that I’d made for Christmas in Prison, with a character sort of delivering a monologue to the reader. I drew a guy standing behind a tree and then I thought maybe he’d reach out and break a branch off. Then it seemed more correct for the broken branch to talk. Most of the stories of these artists begin and end tragically – they undergo a loss, they make something beautiful which is itself destroyed. It seemed right that something broken would tell those stories and that they’d speak from the site of their injury.

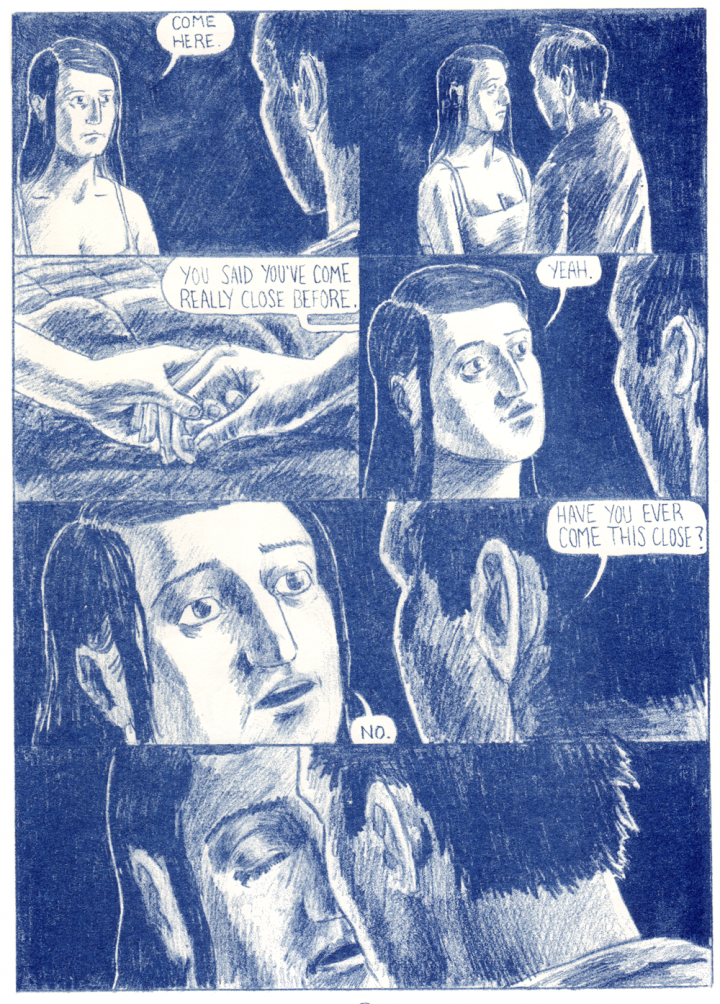

In Generous Bosom, one of your recurring themes is explored thoroughly. We could call it “voyeurism” but it would be simplistic, it is a permanent question about “who watches” and the dynamics of watching. This theme can be found in a lot of your books and is essential in the self-published short story The Dormitory. But who is the real voyeur in your comics, the author or the reader? Or who else?

This is a tough question to answer succinctly. Mostly because it’s still an open one for me since I’m still trying to work these things out…

I don’t think anyone gets to just watch anything without, knowingly or not, participating or altering whatever it is they’re watching. I’m not sure if I can say who is the “real” voyeur.

Maybe comics are based on the fact that the act of watching affects the things you watch at. Can you tell us about your experience as a reader? How do you like to read/watch comics?

I think you’re right. In a comic, there’s no escaping the fact that whatever is on the page was put there by someone and through the act of drawing there’s no difference between what is seen and how it is seen.

That said, on the reading side of it I really like that comics are an elective medium. It doesn’t happen to the audience the way movies do, the audience/reader is the one who animates the action. To answer the question above, I think Generous Bosom is about this dynamic in the reading of comics – that you can pretend that you’re watching something happen both as the reader and creator but in actual fact you are making that thing happen.

I like reading comics over and over. I like that it’s a medium that allows and encourages this; it’s always easy to find a favorite scene again, because there it is. I like that in reading a comic you can go very quickly from the what to the how of a story. The density and depth of really good comics are immediately accessible.

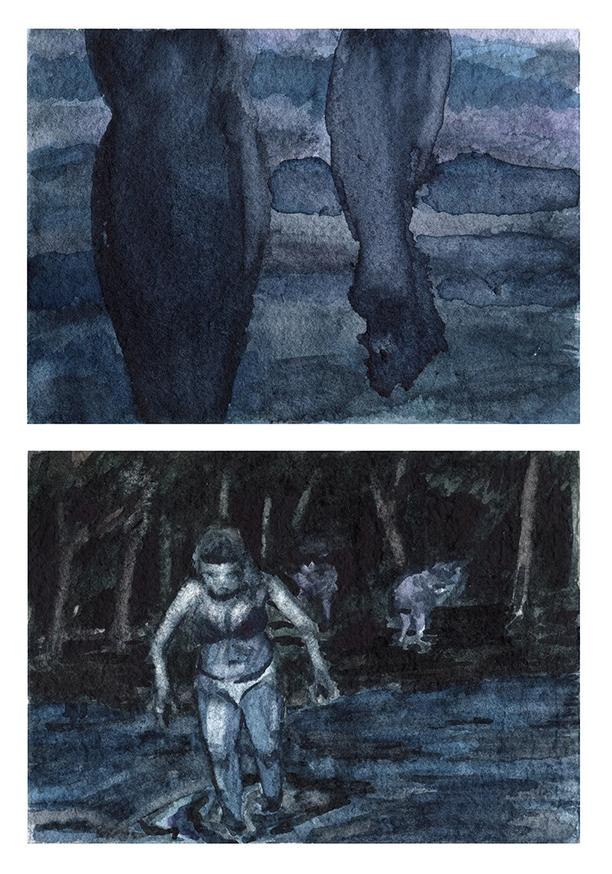

So, this is your idea of reading comics, but what about making them? Your work finds a unique and original way to balance flow and structure, and it is very difficult to understand where you started, if from the plot or from the drawings. Glancing, a work based on the juxtaposition of wordless watercolors, could be an excellent example. What is your idea of comics and narration?

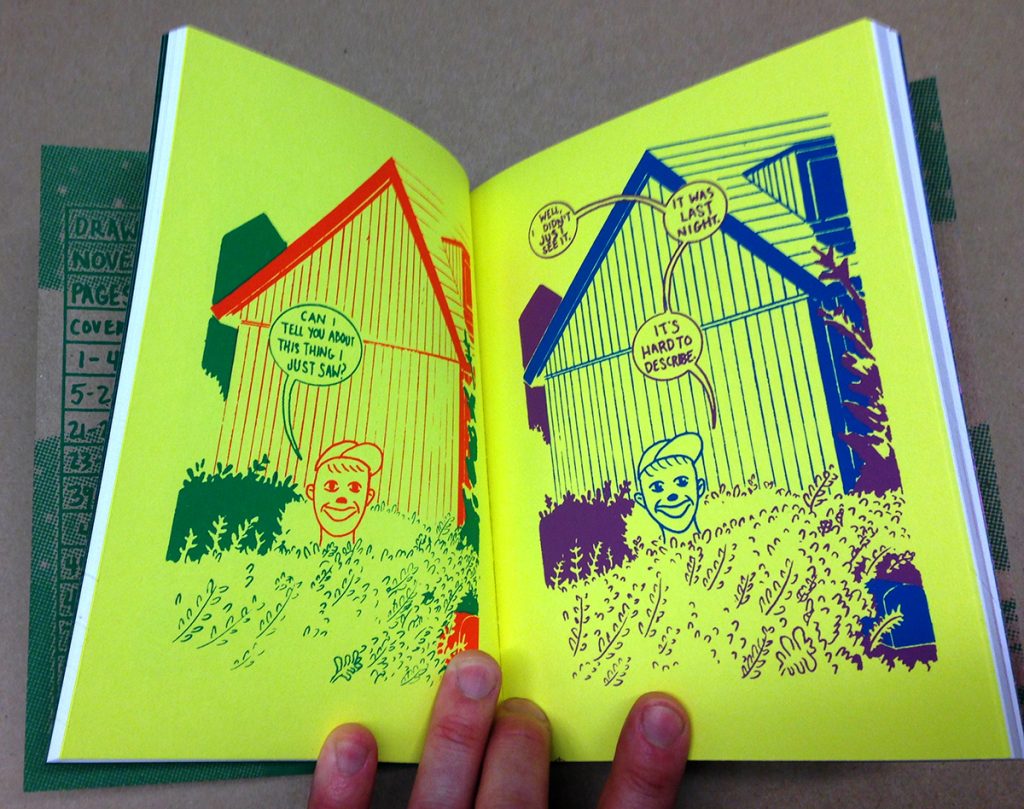

Thank you! I think my idea of comics and narration may go back to your earlier questions about water and the mysterious or irrational arriving in the everyday. Structure = The Everyday = The main narration of a comic/ consistent drawings/ Clarity, while Flow = Mystery = Water/ Change/ Irrationality.

With comics, I’m trying to get things across, to tell an actual story and to do that you have to establish rules that the reader can follow and rely on (I think this is what you mean by “Structure”). These rules start to stack up and can very quickly become impediments to freedom and to feeling like there’s possibilities in the world I’ve created which is where the energy to make more story comes from. At this sort of point it’s time for me to change the rules, insert a different story with different rules, or to maybe work on another project with different or as-yet-undecided rules.

Making Glancing felt very fun and active in this way where I made three or four drawings and then could make more drawings in between those drawings, or after them, or before. I could look at the whole thing laid out on the floor and get a feeling for it comprehensively. I want to make more comics this way.

Another reason of interest in your work is that you generally avoid the opposition between narrative and non-narrative comics – and between fiction and poetry comics – alternating the two approaches or demonstrating their substantial identity in the medium. Do you agree with this perspective?

Thank you again! Yes, I think this also relates to the answer above. I might add that decisions about the structure, whether something is “poetic” or “narrative”, etc. are made by tracking my own excitement about what I’m working on. Bringing in something mysterious/ poetic/ irrational/ non-narrative is often a solution to my becoming bored with a portion of a story or wanting to skip over a part that doesn’t feel compelling to make or to read.

Your work considers both the literary comics developed in the ‘90s and the formal experimentation diverging from the standard of the “graphic novel”, such as Fort Thunder and the output of “art comics” in general. But what is your background? And we aren’t talking only about comics, obviously.

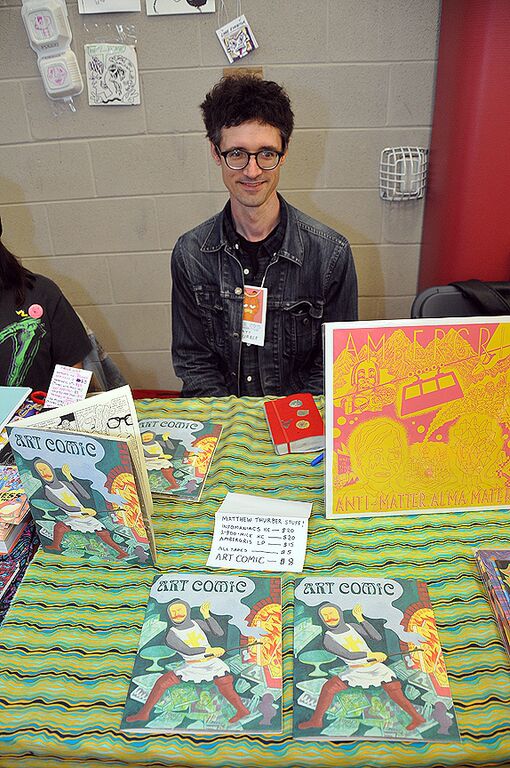

My most important influence is the group of friends that I found at the Maryland Institute College of Art, the folks that made up the Closed Caption Comics group. We all sorted out how to make comics together at a young age. This was exactly the same time that PictureBox was starting up and a lot of the stuff surrounding Fort Thunder was coming to light and that was perfect for us – the immediacy of that work and how it was really visually-oriented spoke to us. Kramers Ergot 4 & 5, the old Fort Thunder Website and meeting CF and Brian Chippendale at SPX gave us all the sense that this was an art world that we could find a place in. And for a good while, I’d say that was about the size of the art world I cared about, it was my circle of friends and those couple guiding lights outside.

Other than that, growing up in rural Pennsylvania has had a huge influence on the imaginary worlds of my books. I also read a lot of literature. I just finished a master’s degree at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago… But are you more interested in my education/influences or in my biography?

Especially your influences, but also your biography, to the extent that it has influenced your work…

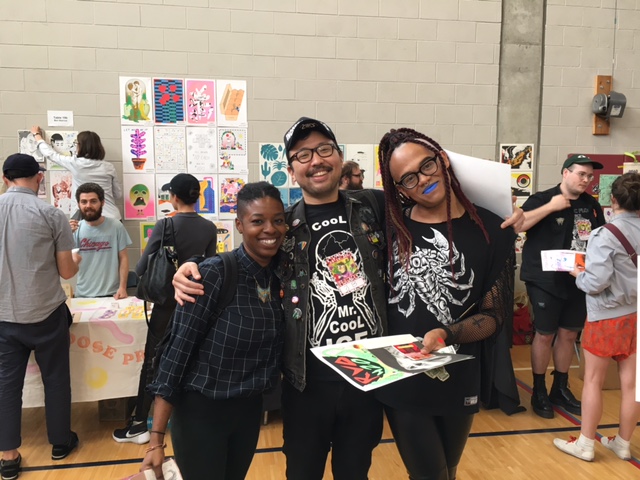

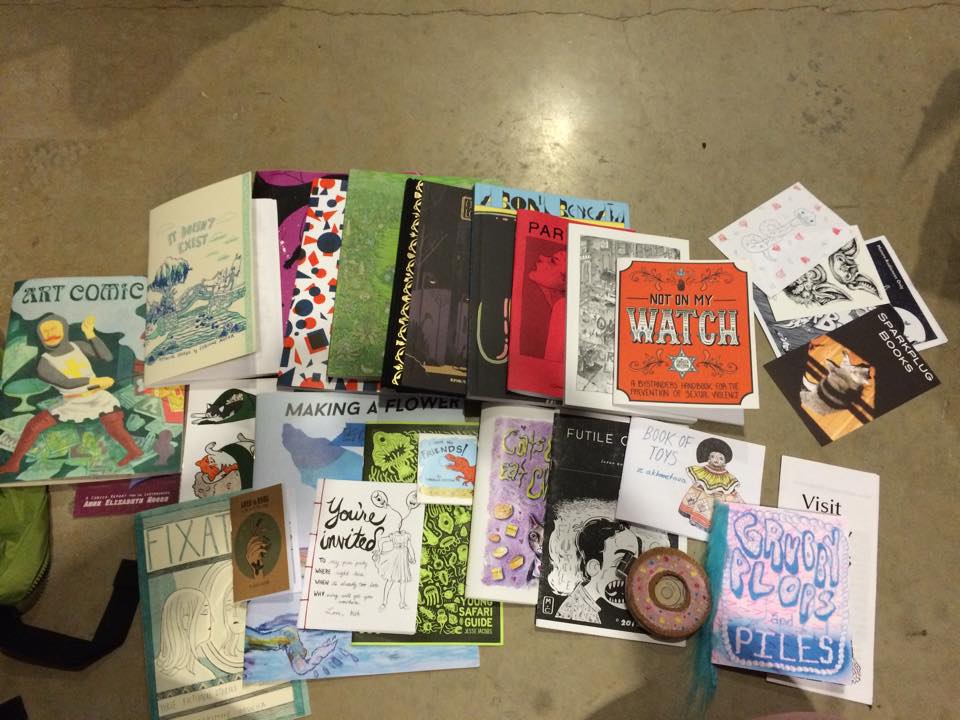

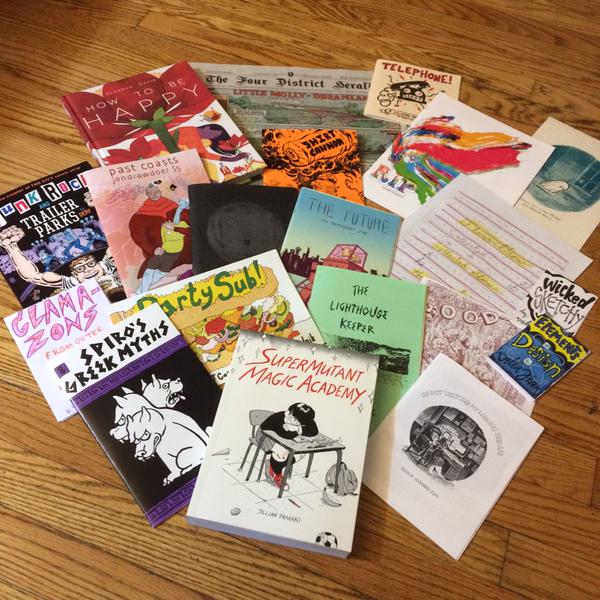

Beyond Closed Caption Comics, I’ve been involved in other collaborative art projects that have had a huge impact on my life. Shortly after school, I helped to found the Open Space gallery in Baltimore. We curated shows, held performances, established a zine library and put on a publications and multiples fair. I’m also helping to organize the first Chicago Art Book Fair here.

I was also in a band called Witch Hat for seven years which I started with Noel Freibert and Lane Milburn. Lane left the band after three years and Chris Day joined. Chris and I are in a new band called Lilac with Anya Davidson and Kenny Rasmussen here in Chicago (Chris and I moved here at the same time). When I got involved in the underground comics scene, there was a lot of crossover with the underground music scene. I met lots of musicians through comics and lots of cartoonists through music.

Do you think your art or your approach to art changed since you moved from Baltimore? Chicago has a big comic scene and a long tradition of contemporary art, we can think to Hairy Who first of all but there is probably much more we don’t know about in Europe.

My art and my approach have definitely changed a lot since moving from Baltimore. I’ve been in school the last two years, so just being exposed to tons of new work and people and ideas has been totally invigorating and overwhelming. I think I’ll be digesting all of it for years to come.

On a basic, lifestyle level, moving here and attending school has allowed me to stop working a non-art-related day job (at least for now). That’s a great gift that I didn’t previously think was within reach for me. I think I’m now more dedicated to the idea of trying to make, or at least to make and to teach, art full time.

As for Chicago, it’s an amazing city for cartoonists. There’s a beautiful supportive community and stuff like the Zine Not Dead reading series run by Matt Davis and Brad Rohloff which carries on the tradition of performative comics reading started by Lyra Hill with her Brain Frame series. I mean just in my neighborhood I’m about five blocks away from a house where Anya Davidson, Lane Milburn, Margot Ferrick and Andy Burkholder all live (Edie Fake used to live there in the attic). A couple blocks in a different direction are my dear friends Molly O’Connell and Chris Day – both of them with beautiful diverse practices that include but aren’t limited to comics and bookmaking.

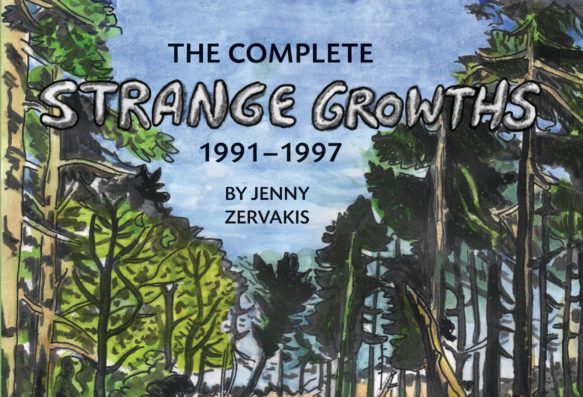

The Complete Strange Growths 1991-1997

Tra la pubblicazione dei primi numeri di Eightball, il debutto dell’Hate di Peter Bagge, la nascita della Drawn and Quarterly con il lancio di serie regolari a firma di autori come Seth, Chester Brown e Joe Matt, il periodo a cavallo degli anni ’80 e ’90 ha segnato una notevole rivoluzione per il fumetto nord-americano, trasformando definitivamente il concetto di fumetto “underground” e “indipendente” come era concepito fino a quel momento. Innanzitutto le storie di questi cartoonist si proponevano con un linguaggio nuovo e meno autoreferenziale rispetto al passato a un pubblico più vasto, e in secondo luogo alcuni di questi autori uscivano dagli schemi abituali del fumetto “alternativo” come veicolo di contenuti esclusivamente anticonvenzionali, sarcastici, iconoclasti, provocatori. Se la qualità di quel materiale rimane uno dei vertici raggiunti dal fumetto nei suoi tanti anni di storia (almeno dal limitato punto di vista di uno che quella “roba” ha cominciato a leggerla in piena adolescenza, rimanendone irrimediabilmente colpito), è doveroso dire che gli autori citati in precedenza non erano gli unici a portare nuova linfa nel panorama del fumetto a stelle e strisce. Sotto, nel più profondo dei mondi della micro-editoria di cui in Italia poco si sapeva nell’epoca pre-internet – a meno di non incappare in una pubblicità o addirittura in una recensione su The Comics Journal – si muovevano una serie di autori misconosciuti che consapevoli della rivoluzione del do it yourself applicavano i principi produttivi del punk alle loro esigenze, dando vita alla cosiddetta “zine revolution”. Tra questi una delle prime fu Jenny Zervakis, chicagoana di origini greche che nel 1991 cominciò a autoprodursi la fanzine Strange Growths, “strana” come il titolo suggerisce per il modo in cui mette in pagina senza mediazioni racconti autobiografici, aneddoti raccolti sull’autobus, poesie scritte a macchina, ritratti degli abitanti del quartiere, dettagliate descrizioni di sogni, diari di viaggio, riflessioni, saggi in forma di fumetto, disegni di animali, piante, giardini. Il tutto rappresentato con uno stile che definire scarno è poco, dato che la bozza, l’approssimazione, la semplicità erano conseguenze dirette dell’urgenza espressiva, e la ricerca della perfezione formale o della bellezza semplicemente non interessava.

Dei primi 13 numeri di Strange Growths è uscita da poco una raccolta assemblata da John Porcellino e pubblicata dalla sua Spit and a Half, prima opera di un altro autore che esce per l’etichetta (e distribuzione) dell’autore di King-Cat Comics. La scelta non è casuale, perché la Zervakis è stata una fonte di ispirazione per Porcellino e per tutto il movimento dei comics as poetry. “I suoi fumetti sembravano come una trasmissione da un altro pianeta – scrive l’editore nella sua introduzione al volume – un mondo di ironica compostezza, suggestione poetica, raffinata capacità di osservazione, a volte caldi e altre freddi, oppure tutte e due le cose insieme. Forse non c’è bisogno di dirlo, ma per chi non conosce i fumetti che venivano pubblicati in quegli anni, non c’era niente di simile. Mentre la gran parte dei fumetti “alternativi” dell’epoca erano chiassosi e sarcastici, quelli di Jenny erano calorosi, emozionanti, sinceri e sorprendentemente complessi”. “Jenny Zervakis – aggiunge Rob Clough nell’intervista all’autrice che chiude la raccolta – è nata nel 1967 nel West Side di Chicago, e fa parte di una generazione di artisti che reagì alla prima ondata di cartoonist alternativi dell’inizio degli anni ’80, oltre che di una cultura legata al punk, alle fanzine e al do it yourself che è esplosa con la nascita del desktop publishing. Le sue attente riflessioni e la propensione a rappresentare l’immobilità sulla pagina furono tra i primi esempi di comics-as-poetry”.

Come accennato, nel volume troviamo tutto il ventaglio dell’offerta della Zervakis, che alla molteplicità degli argomenti e dei toni unisce varietà nella composizione della pagina e nella costruzione dei diversi pezzi. Le storie non sono mai banali né ripetitive, anzi esprimono voglia di sperimentare e curiosità nelle mille possibilità del medium. I testi ricchi di passaggi poetici e di consapevolezza letteraria fanno capire chiaramente che la Zervakis è più scrittrice che disegnatrice, ma sua è anche una notevole capacità di mettere in scena inquadrature e soluzioni stilistiche “sorprendentemente complesse”, come scriveva Porcellino nell’introduzione, oltreché di regalarci alcune tavole più dettagliate e intense delle altre, soprattutto quando la natura diventa la vera protagonista della rappresentazione. I risultati migliori sono raggiunti quando il particolare, apparentemente insignificante, diventa occasione di riflettere sull’universale, catturando la poesia e anche la complessità delle piccole cose con una scrittura lirica, pregnante, emozionante: Passing Time è il ritratto di una donna anziana intenta a lavorare a maglia (She sits knitting as if she is done living her life and instead pours herself out, stitch by stitch, into some future generation / She has grown her hair, plaited on her head, past any usefulness, past admiration of its beauty to the sheer oddity of persistence), in Silent Passenger una coppia torna a casa di notte mentre la donna (con tutta probabilità la Zervakis stessa) viene colta contemporaneamente da meraviglia e insicurezza (Coming home it was 2 AM beautiful / Someone’s singing / It’s only humans that make music for the sheer joy, the need of it, maybe so / I wish I could seduce you, all over again), Chuparrosa guarda al mondo animale per riflettere sulla vita umana (Sometimes I feel there is a world beyond our petty concerns / While I sit, consumed with my thoughts and worries, birds fly overhead through the rows of backyards). The Complete Strange Growths non è soltanto un pezzo di storia del fumetto autoprodotto statunitense ma anche una lettura appassionante, uno sguardo su un mondo intimo e personale capace di trascende la cronaca del quotidiano per emozionare ancora, a distanza di oltre vent’anni.

Misunderstanding Comics #9

Iniziamo questa nuova puntata dell’usuale ma aperiodica rubrica di segnalazioni varie con Steam Clean, un volumetto brossurato di 84 pagine a firma Laura Ķeniņš, cartoonist metà lettone e metà canadese di cui avevo già segnalato l’ottimo mini-kuš! #42 Alien Beings. Con questa nuova uscita, stavolta targata Retrofit Comics, la Ķeniņš conferma quanto di buono fatto vedere in precedenza, trasformando una situazione apparentemente ordinaria come una sauna tra donne in una meditazione sull’identità di genere, la sessualità, i rapporti interpersonali, il conflitto tra tradizione e modernità.

La rappresentazione tutta colori pastello dell’ambiente nordico e la regolarità quasi schematica delle vignette restituiscono un’atmosfera rilassata, in cui sembra di percepire con le nostre orecchie il silenzio di sottofondo. E neanche i dialoghi fitti rompono questa sensazione di pace, inalterata persino quando si esplicitano tensioni nascoste ed emerge un’aura di sovrannaturale mistero, con un’apparizione divina e spiriti dai contorni naif che aleggiano tra i fumi del vapore. La Ķeniņš propone ancora una volta un cartooning consapevole, rigoroso e maturo, capace come pochi di raccontare personaggi in una fase di transizione. E anche di farci sentire lassù, in quella sauna tra i boschi.

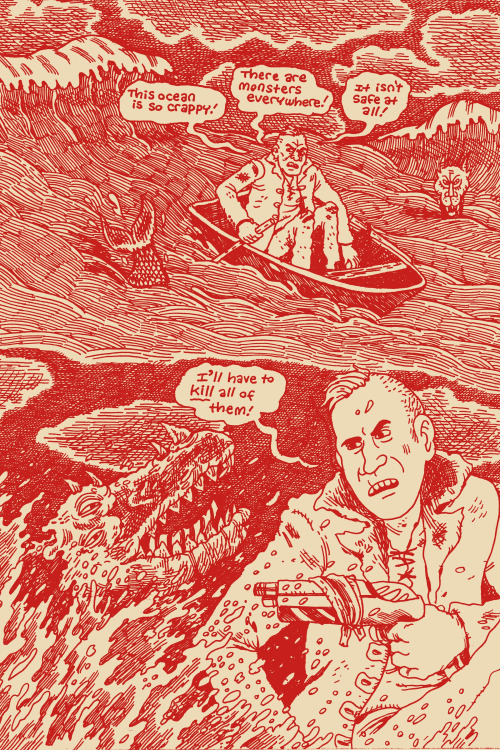

Se il volumetto della Ķeniņš sembra ricordare i film del norvegese Bent Hamer, il secondo numero dell’antologia-libro Mirror Mirror edita da 2d Cloud guarda a tutt’altro immaginario cinematografico, come la presenza di alcuni contributi a firma Clive Barker lascia intuire. Sotto la cura congiunta di Sean T. Collins e Julia Gfrorer, il volume mette in fila 230 pagine di fumetti e illustrazioni incentrate su un’idea di orrore legata al quotidiano, al corpo e infine alla pornografia. Eccellenti premesse dunque anche se l’antologia è appunto… un’antologia, con i suoi alti e i suoi bassi, e una buona metà dei lavori che risultano piuttosto ordinari, per niente disturbanti né trasgressivi come lascerebbe intendere il progetto, nel complesso troppo pretenzioso rispetto a quanto proposto. Nonostante ciò, di cose buone qui dentro ce ne sono eccome, per esempio il solito subdolo horror delle meschinità umane a firma Josh Simmons – particolarmente a suo agio con i campi lunghi, quasi a sottolineare anche graficamente l’abituale distanza emotiva – oppure Black Flame, un racconto in cui ritroviamo la Megg di Simon Hanselmann alle prese con il suo “lato oscuro” e che è l’occasione per vedere l’autore australiano confrontarsi al tempo stesso con testi altrui (Sean T. Collins) e con un bianco e nero massimalista fatto di pennellate ben più corpose del solito. Al Columbia (con i suoi Pim & Francie), Uno Moralez, Noel Freibert e Dame Darcy danno a loro volta un notevole contributo, pur attingendo ispirazione al loro rispettivo e usuale canone.

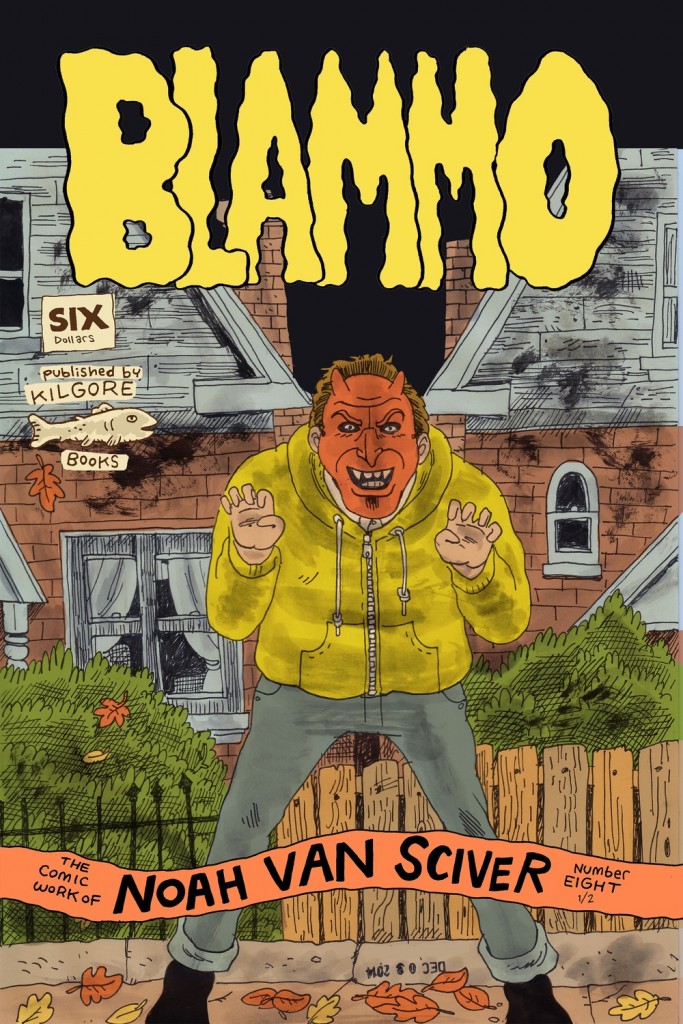

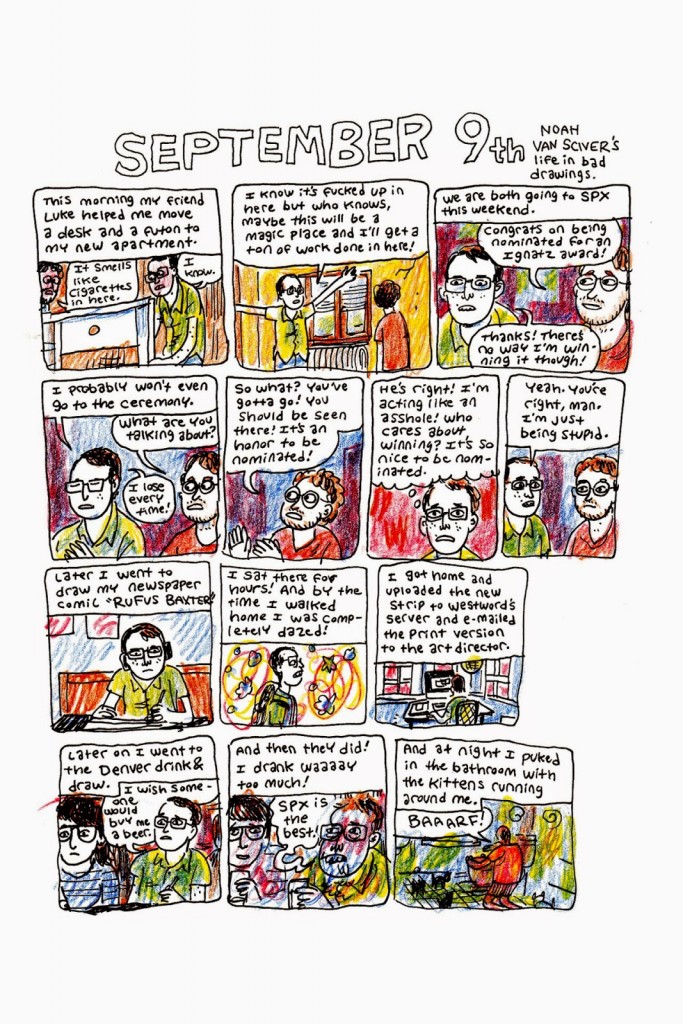

E veniamo a una nostra vecchia conoscenza, cioè Noah Van Sciver, che è tornato di recente al suo personaggio Fante Bukowski pubblicando per Fantagraphics il secondo capitolo delle sue avventure, séguito del debutto del 2015 tradotto in Italia da Coconino. Come lascia intendere lo pseudonimo che si è scelto, il protagonista è uno “scrittore” che vive nelle camere di hotel e usa ancora la matita o al massimo la macchina da scrivere, va con le prostitute e beve solo per darsi un tono. Fante non ha nessuna voglia di scrivere e soprattutto non ha talento: la sua missione è raggiungere lo status di artista, essere amato e invidiato dagli altri come lui invidia i “colleghi” che ce l’hanno fatta. Se la prima uscita originale ricalcava il formato romanzo tascabile, la seconda amplia i centimetri e sceglie una grafica retrò in odore di anni ’60, mutuata dall’edizione Black Sparrow Press di Factotum.

Ma soprattutto se nella prima parte si sorrideva, in questa si ride di gusto, e a me è sembrato di non divertirmi così tanto dai tempi dell’Hate di Peter Bagge, pietra miliare dei comics anni ’90 uscita sempre per Fantagraphics. Vi anticipo solo qualche gag iniziale per non rovinarvi troppo la lettura, come quella in cui Fante rompe una matita in due perché è “troppo gialla” e non riesce a concentrarsi sulla scrittura. E il capitolo in cui decide di pubblicarsi una fanzine di poesia (“Sì, sarò l’editor! Sarò il boss! Accetterò tutte le mie proposte!”) è esilarante. Il trasferimento del protagonista da Denver a Columbus sembra anche autobiografico, ma poi a un certo punto ecco spuntare l’autore in carne e ossa, vittima di una divertentissima auto-parodia, nonché rivale in amore di Fante. Sullo sfondo, e neanche troppo, si muovono riflessioni sulla scrittura, il successo, l’ambizione e la vanità che non lasciano affatto il tempo che trovano, rendendo questo Fante Bukowski Two una delle migliori prove a firma Van Sciver.

Quando viveva a Denver, Van Sciver lavorava da Kilgore Books, negozio di libri e fumetti che è anche una small press dedita alla stampa di mini-comics e non solo. Prodotto di punta è il Kilgore Quarterly, antologia tutt’altro che quadrimestrale uscita di recente con un settimo numero molto più ricco del solito, nascosto dietro a una bella copertina di Jason (rilettura di Le Mal du Pays di Magritte) e come sempre a cura del padrone di casa Dan Stafford.

Il volumetto, che propone in parte storie già pubblicate altrove o di prossima pubblicazione, si apre con Dappled Light di Summer Pierre, una storia di 5 pagine leggera e al tempo stesso malinconica, ritratto autobiografico di una bambina che grazie al fumetto può finalmente rifugiarsi, in senso letterale, nel mondo dei vecchi telefilm. Si prosegue con la solita intervista scritta a mano (vezzo di Stafford da sempre, come testimonia la raccolta I Hope This Finds You Well con interviste a Crumb, Tomine, Bagge ma anche a Ian MacKaye, Doug Martsch, Dan Fante e altri) al cover artist Jason e si raggiunge l’apice con Steve McQueen Has Vanished, storia “vera” della sparizione dell’attore raccontata con il solito dettagliatissimo stile da Tim Lane, anticipazione del prossimo lavoro dell’autore di Happy Hour in America e The Lonesome Go. Dopo una inaspettata quanto sintetica chiacchierata con Grace Slick, si passa a un più canonico ma validissimo pezzo underground di Joseph Remnant, tra sfighe quotidiane e ricerca dell’amor perduto, dunque ecco Sam Spina con quattro divertentissime pagine metanarrative che vedono il suo alter-ego pesce alle prese con app e sesso occasionale, e infine la riproposizione di un fumetto di Leslie Stein, The Desk, già uscito in formato mini per Oily Comics e forse il contributo meno significativo del lotto. La terza di copertina è dedicata a qualche nota autobiografica nel solco della più piacevole tradizione del self-publishing a stelle e strisce, a ricordarci che di antologie così curate e con un feeling do it yourself ne vorremmo ancora e ancora.

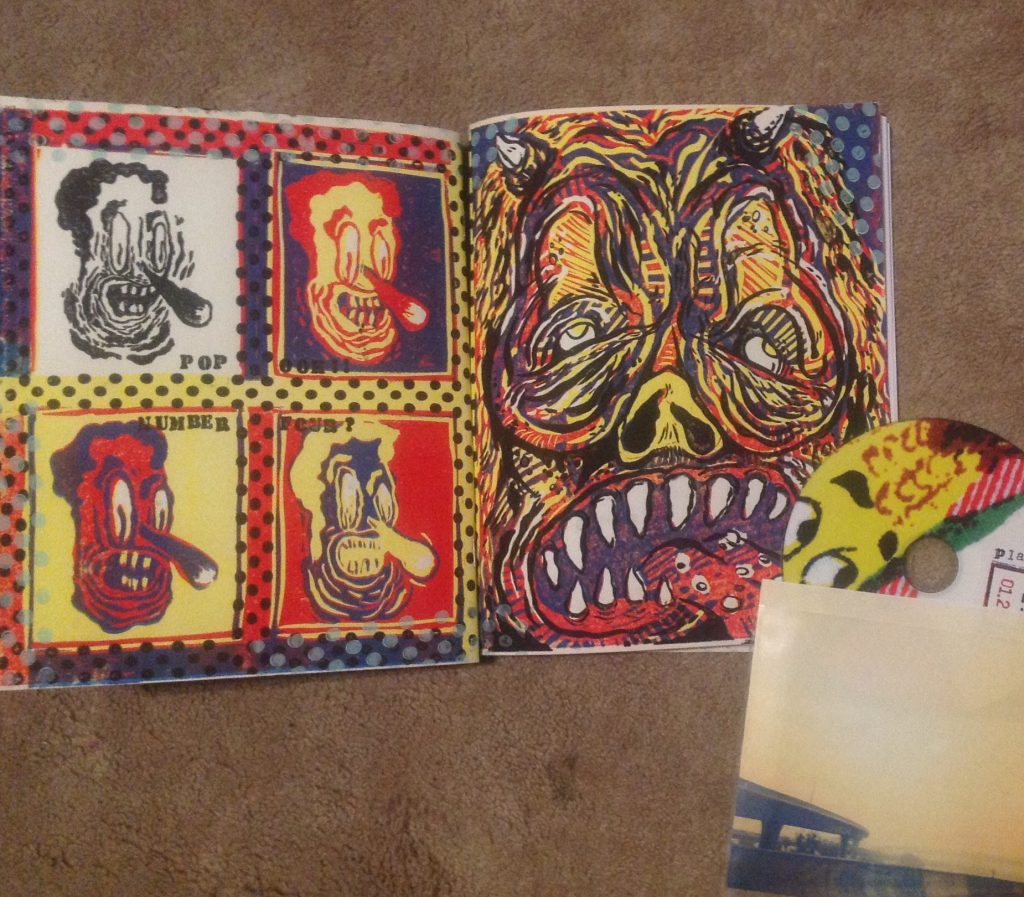

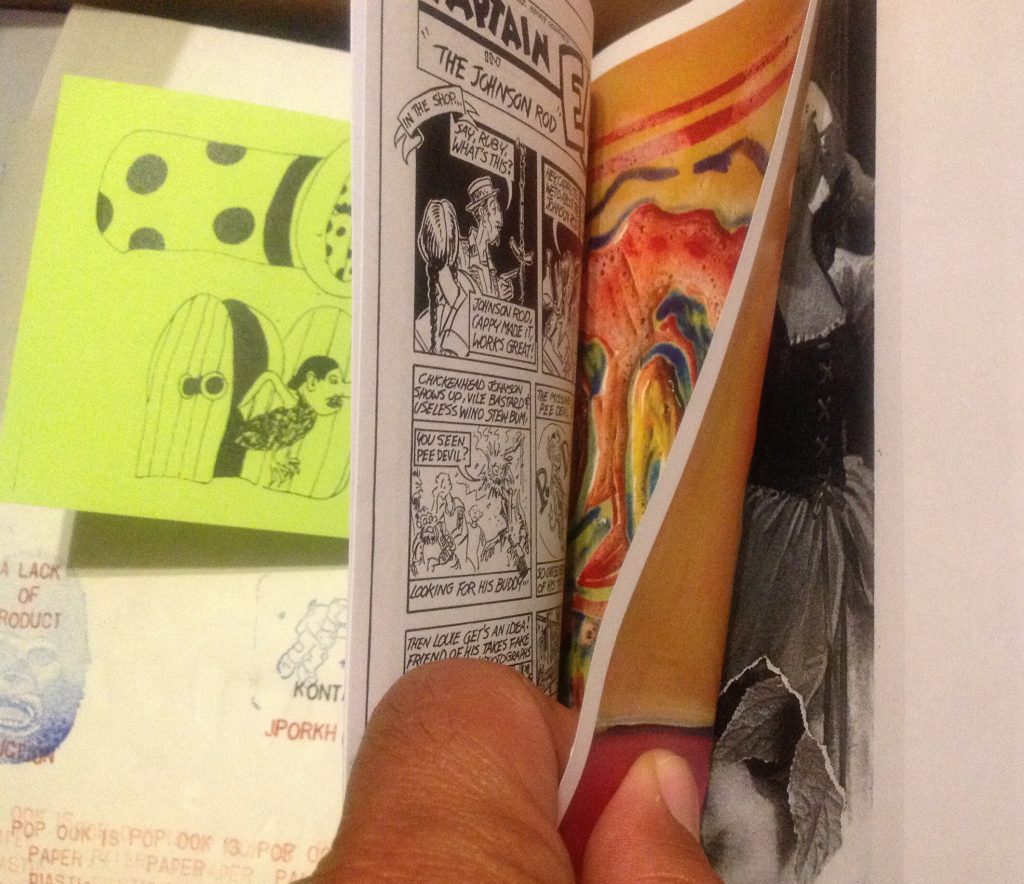

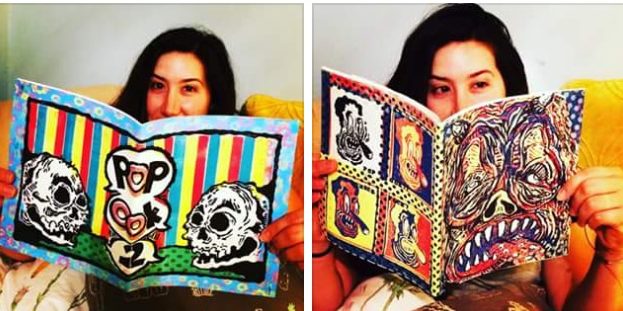

PopOok! An interview with Hamo Bahnam

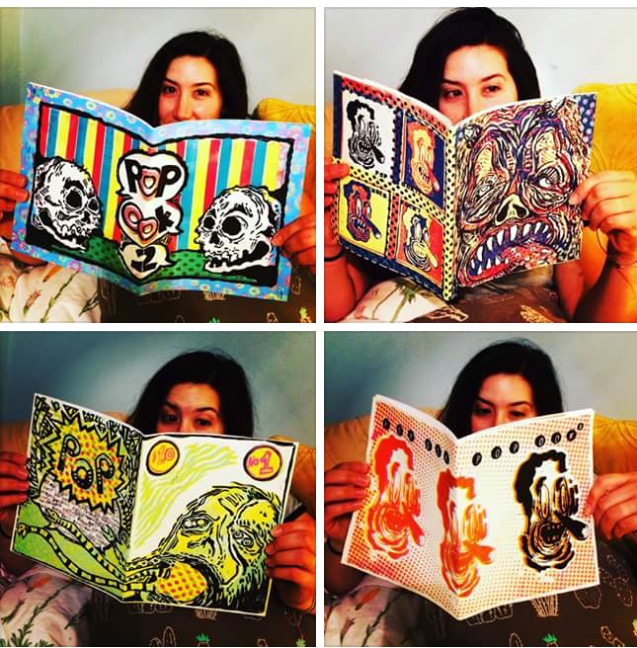

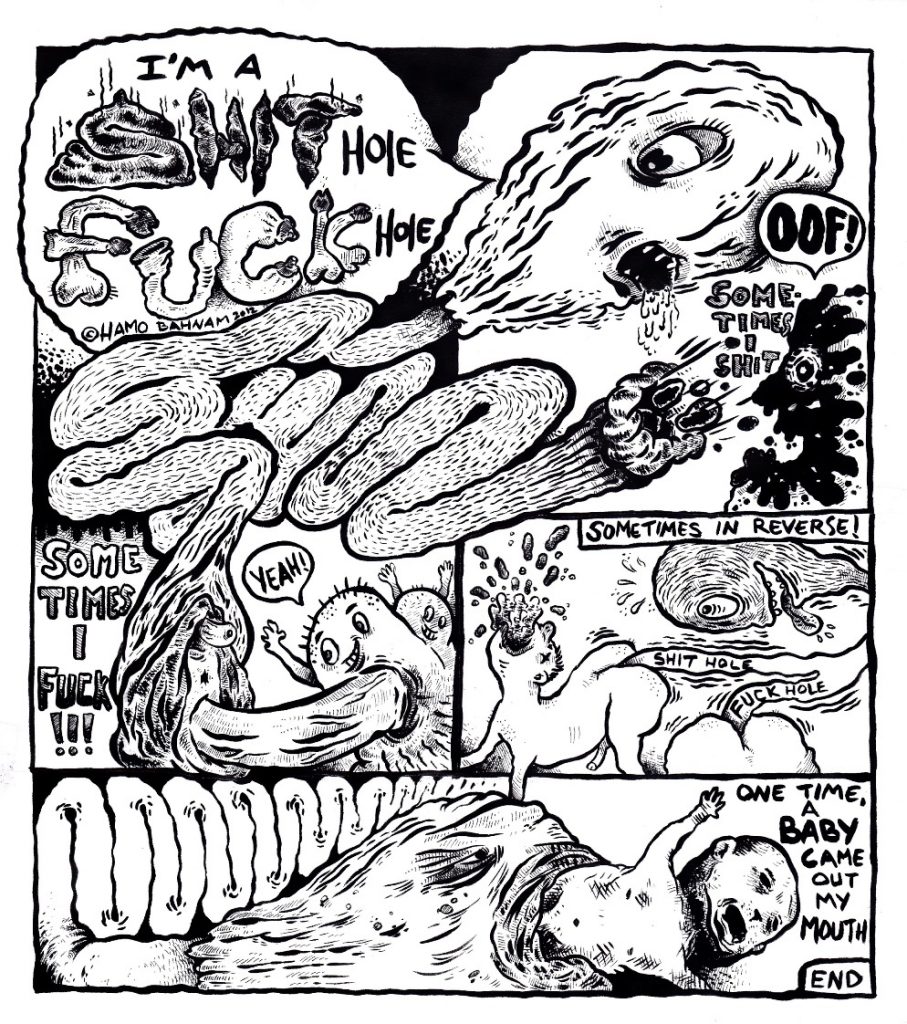

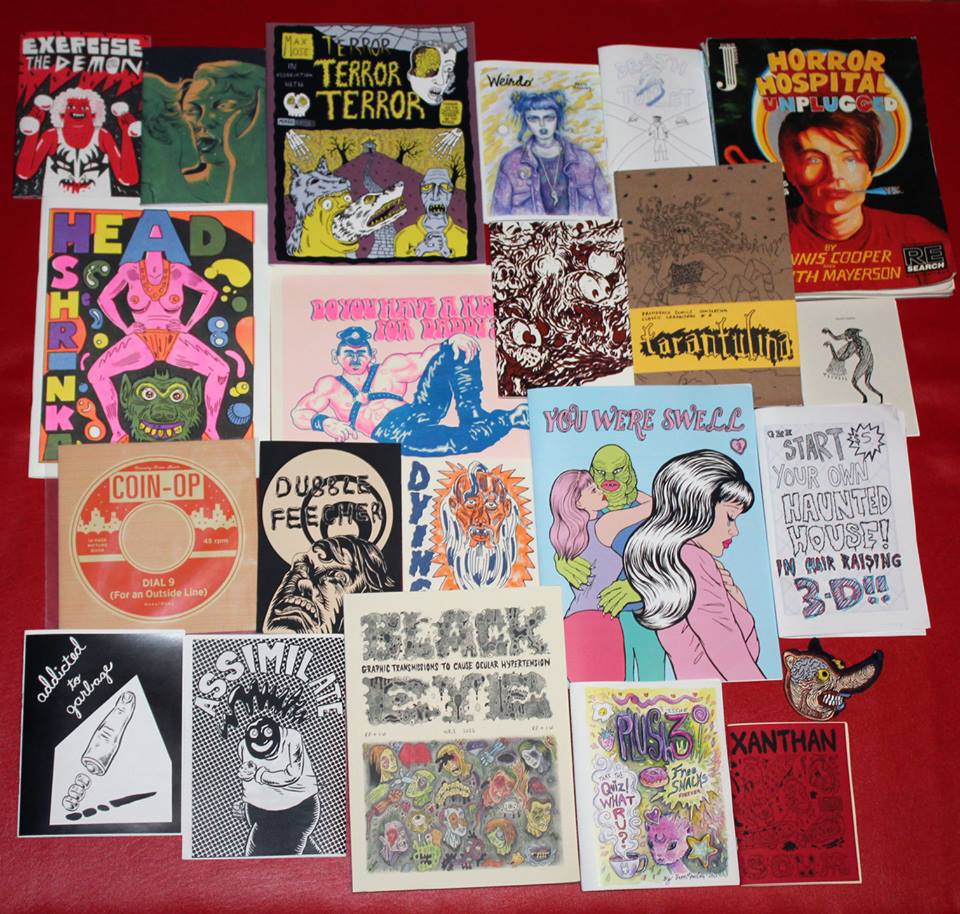

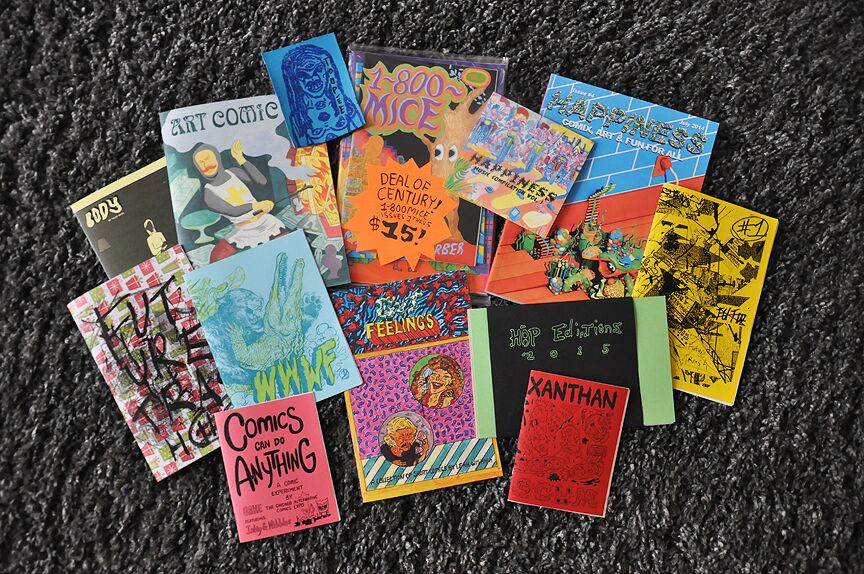

PopOok! is a Los Angeles-based zine self-published by Hamo Bahnam since 2012 and now arrived at its fourth and recent issue. When Hamo introduced me to his project, I wasn’t aware of it and I think a lot of other people really into self-publishing, zines etc. still don’t know about Pop Ook!. In fact, in a world where you can find almost everything on the social networks and in a scene where every cartoonist knows his peers, PopOok! is an exception, the kind of publication that can’t live anywhere else but on paper and whose creators don’t aggressively promote it, because they simply want to do it, without caring too much about the audience’s acceptance. Inside the issues of PopOok! there are very different contents: comics looking directly to the underground revolution like the ones created by Bahnam, the strange cartoons of Rusty Jordan already known for Alamo Value Plus published by Revival House Press (I talked about it on the old website), the nightmares of Marcel Dejure and the “wet dreams” of Yara Zair. And then collages, illustrations, inserts on colored paper, plus a cd of ambient-noise-experimental rock music coming with every issue. All this comes wrapped up in hand printed covers. Not every page is completely accomplished but there is a feeling here of something going on, a love for the subject matter that isn’t related to self-realization but only to real love for comics, music and illustration. I’ve talked about PopOok! with its master Hamo Bahnam in an interview conducted via e-mail in the latest months.

The first issue of PopOok! was published in Spring 2012 but you made comics long before. Can you tell me when you started to create comics, where you published them and how the idea of starting PopOok! was born?

Comics have always been a big part of who I am as an artist. Not really as a fan knowing the hippest books and artists but as an aesthetic, a way of working. I’m more interested in music as a fan than I am in any kind of art. But my wanting to be an artist comes from buying my first copy of Mad magazine when I was 10 years old. I put out my first comic in 1994. I called it Grow Up! (comix and funnies). That first comic was a precursor to what I’m doing with PopOok!. The idea that I could publish my own comics and zines came out of the punk/hardcore culture I grew up around. Comics and degenerate music have a long history together. From 50’s horror comics and juvenile delinquents listening to rock’n’roll to the 60’s underground comix and psychedelic music to punk (Punk magazine’s John Holmstrom and Gary Panter) to 90’s garage and even noise music has artists and cartoonists involved. Low forms of culture breads other low forms. In the early 90’s met two artists, Amos and Marcel Dejure, who were publishing books under the No (Know) information Network. They published me first in their HO! Comix. They hooked me up with other artists and that’s where the idea of Grow Up! came from. I stopped making comics for a while and concentrated on painting and printmaking, however, comics were usually a theme in the format I was working in. Around 2005 I started making comics again for a leftist newspaper in Knoxville TN. The comic came out twice a month. It was called Juicy Pork Head. About a corrupt industrialist named Harry Bowels, who hypnotized children into killing their parents, then turned the dead parents into ice cream. That scenario would fit into todays’ political climate quite well actually.

I started PopOok! in 2010 when I moved back to Los Angeles after being gone for 12 years. I needed an artistic direction and a focus after separating from my ex-wife. I met Meredith Wallace who was a co-worker with me at a local library. We began talking and it turned out she had a small zine distribution company. She eventually became instrumental in starting the L.A. Zine fest and I just figured this would be a great moment to start making comix again. I invited some old friends to contribute and met some new folks and Bingo! PopOok! was born. I took what I learned from years of printmaking, comix reading and my love for music and now I’m working on a fourth and fifth issue.

The zine is “a lack of Product production”, while the music cds coming with every issue are credited to Plastic Factory Records. Are only you behind these labels or there is someone else?

Yes, it’s just me behind those labels. Artist and musicians send me their work and I put it all together. I create comics and music too then I assemble the whole thing, I hand print the covers then cut, staple or glue. I’m the owner/publisher/editor/labor and janitorial staff. But I couldn’t do it without all the talented people who contribute to it. I make enough money from sales to cover my costs and the contributors get no salary. They do it for free and I guess they trust me to make a product they can stand behind. I love them all for believing in this project.

And so, how you select these artists? Are they people you know in the “real life” or you contact them on the internet? Because, seeing it from the outside, PopOok! seems the expression of a scene and it could seem a zine of another time, when social networks still didn’t exist. I don’t see in it “famous internet people”…

Most of the people involved are friends and acquaintances that I’ve known for some time. Some of these friendships go back 20-30 years. Others I’ve just recently met because of my doing PopOok! Or friends at work who are creative types. Some people I meet at zinefests and music spaces where I see/hear their work or they see mine. And also others are people I’ve never met that I have admired their work from seeing/hearing it on the internet. As far as a “scene” goes most of the artists/musician have never met each other! Some do know and are aware of each others work but it’s mostly a scene comprised of many cities and countries and PopOok! provides the glue that binds them together.

What are your inspirations both as an editor and as a cartoonist? Ok, you were influenced by Mad magazine but I guess you also love the underground comics from the 60’s or the 70’s, because most of the works in PopOok! can rememeber Zap Comix and sometimes they have a psychedelic style or a punk feeling. On the whole your zines seem a sort of “old school” work, as if the people who created them love the classics while they aren’t really interested in the latest tendencies of cartooning. And this is pretty strange in a world where everything looks like something else…

Yes, Punk and Underground Comix culture are two big influences on me. As a cartoonist my influences are many and they are one’s that I’ve held on to for a long time. Robert Crumb is godhead to me. He’s just an incredible talent and genius that changed me forever. Of course with Crumb comes the Zap artists: Clay Wilson is fantastic as well as Gilbert Shelton. The Harvey Kurtzman years at Mad, especially the cartoonists Will Elder and Jack Davis. Later Mad artist Don Martin was a childhood favorite only replaced when Crumb walked into my life. George Herriman and the absurdity of Krazy Kat. I love absurdity in everything! And also the raw energy of Savage Pencil and Gary Panter are always present for me.

As an editor my two influences would be Robert Crumb and Art Spiegelman. Crumb’s embrace of punk cartoonists and punk culture when he published Weirdo plays a huge part on me with PopOok! And Art Spiegelman’s RAW magazine is great too. The multifaceted aspects of Spiegelman’s work is top notch. As an editor my influences do come through in the contents of the comic and music cd. I think the old school aesthetic comes from my age and what I grew up on. I’m old enough to have been alive for those things to be new. Those artists are my teachers.

Another feature of the zine is that every issue is very “physical”, the packaging is really accurate and there are a lot of inserts, you use different paper colors, the covers are mostly printed using linoleum blocks and hand stenciling, and one is silkscreened (#3). These are books you absolutely can’t read as a PDF…

Right. And that goes back to Spieglman’s Raw. I have a copy of #7 where he tore a piece of the cover off and taped it to the inside. And the original chapters of Maus where printed and stapled inside the bigger comic as a mini book. So that playing with the medium, how he deconstructed/tore-apart comics is fascinating to me. I’m also a printmaker and make assemblage paintings so the physical object is very important to me. The human artifact speaks to me and the need to touch things to have an actual experience with art is what I’m going after. I’m strictly a 20th Century boy. PDF comics are bullshit.

Would you like to present to the readers of Just Indie Comics some of the cartoonists you’re working with for PopOok!?

Sure. All the artists are worth mentioning and there are so many but we can talk about some of them.

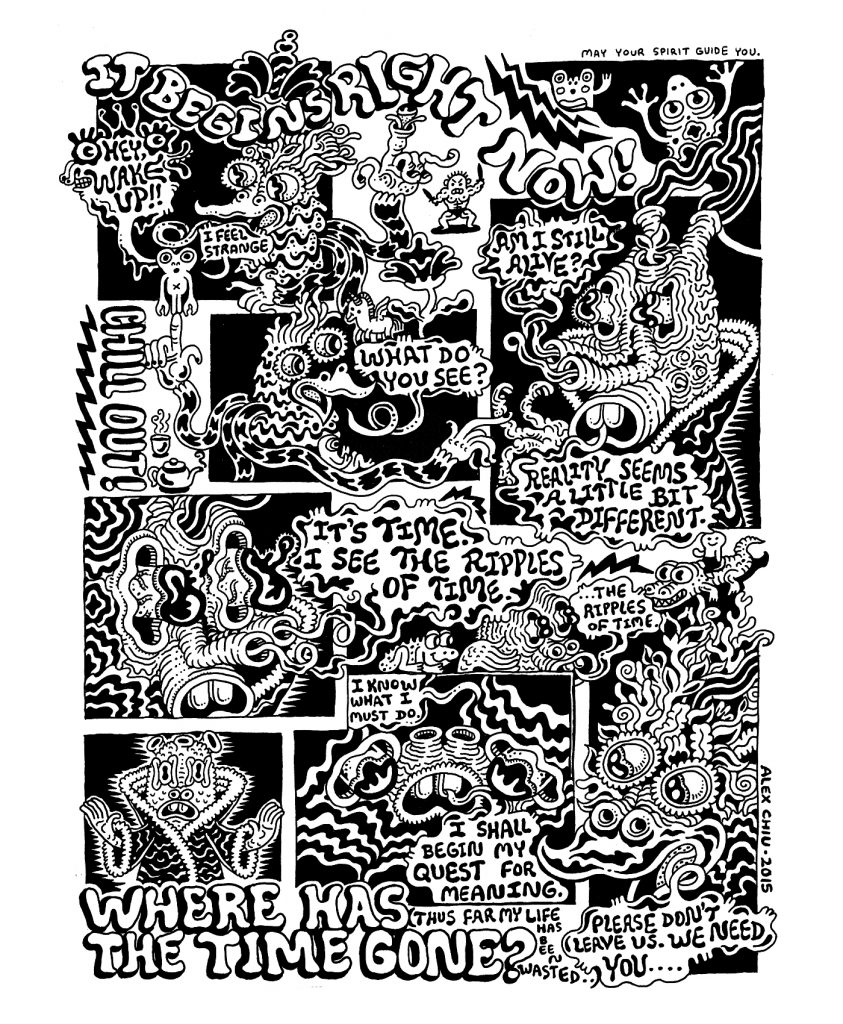

Alex Chiu and Rusty Jordan are two artists I met while they lived here in Los Angeles. They both moved up to the state of Oregon a while back. Alex is a prolific artist who creates complex, fanatical drawings in a crazed, almost a free associative, doodle style. He not only paints, teaches, does comics, runs a small publication press called Eyeball Burp but also is creating illustrations for children’s books all while having a YouTube cooking show with his daughter!

Rusty is a cartoonist whose work features characters who remind me of the people that occupy the world of writer Bohumil Hrabal. With absurdist, lonely yet loveable “everyman” losers in a very American setting. Rusty is a sign painter by trade but also publishes comics. I first saw his work in a collaborative comic named Moulger Bag Digest. He also puts out Alamo Value Plus and created the anthology series Shitbeams on the Loose.

Marcel Dejure and Amos. Marcel’s comics are claustrophobic punk rock acid trips. Roller skaters, burnouts, porno queens, meth-heads, drugged out animals and other Los Angeles dissidents make up his transgressive world. Marcel rarely makes comics anymore but when he does they’re for Popook! He spends countless hours working on a fashion line of clothing that combines the erotic with cartooning. He’s also the creator of the live puppet performance group Cinnamon Roll Gang.

Amos’ work mixes dystopian landscapes with bebop jazz and drugs. He loves his cats who once in a while make it into his comics. I’ve been a great admirer of his work for many, many years. He’s a printmaker as well and has worked for the legendary print collective Self-Help Graphics in East Los Angeles.

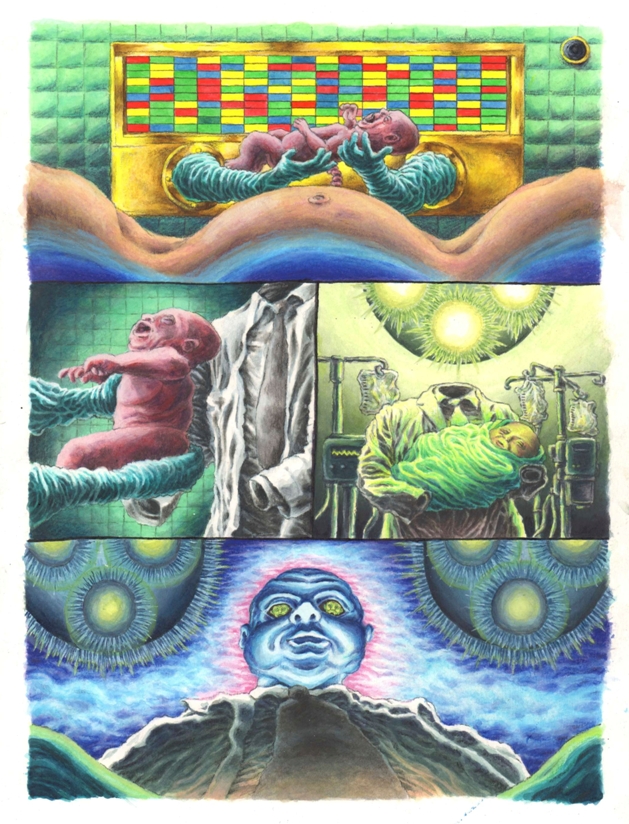

David James-Dimitrov is a Canadian cartoonist and painter. I met him online and he sent me copies of his incredible no text comic A Sunburned Heart in the Skin Celled Desert. His work is incredibly detailed and lovingly rendered. Science fiction dream stories… Mixing a weird combo of Twilight Zone and Alejandro Jodorowsky.

And what about the musicians?

Bryan Davis makes music as Bleeding Gorgon. I first met Mr. Davis in Knoxville, Tennessee when he was video taping my band for his public access show Kill Your Television. An artist and filmmaker, I never knew he made music until he submitted some prerecorded, phone called, industrial noises to the first PopOok! His more rockin’ tunes are a combination of the bands Chrome and the Humpers. He writes songs of loss, rejection, abandonment and loves horror movies and punk.

In the years 2005-2011 Grant Capes co-ran the alternative art/music space Echo Curio in Los Angeles. The Echo is where the seeds of PopOok! germinated as I met artists and musicians that would fill the pages and sounds of the comic/cd. His current project is Borne on a Train, a podcast series where he showcases live performances from some of Los Angeles’ premier experimental musicians. He has contributed to the first four issues of PopOok!, mostly under the Sleepwalkers Local moniker. Sleepwalkers Local is an improv situation involving Grant and whatever instruments are about. The set of songs included in the new issue of PopOok! comes from an old piano and a newly acquired harmonium and chord organ all processed for your enjoyment.

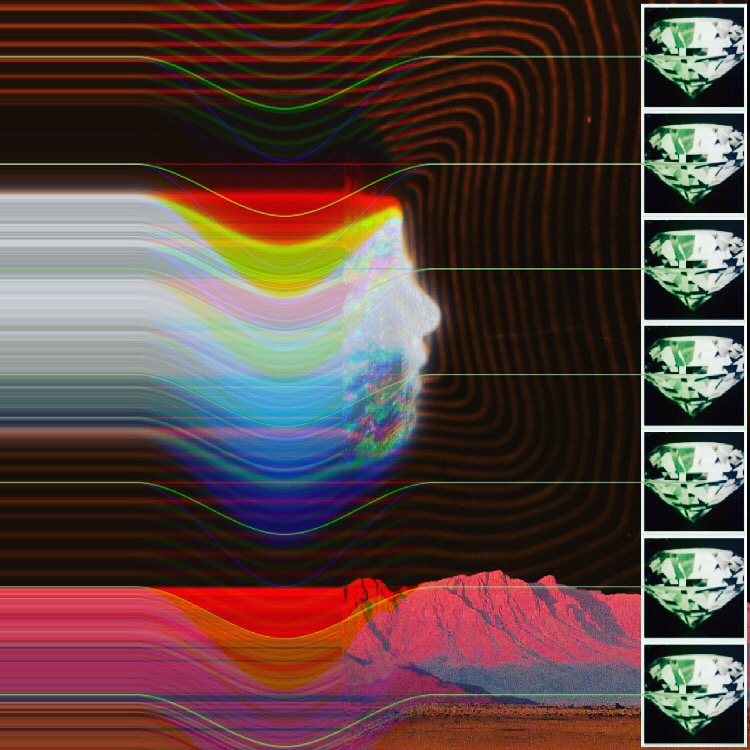

I’ve been waiting a long time now for Charlie Finch (Professor Husband) to release the vinyl debut of his The Diamond Trip multimedia project. A bit ambient, a bit spacerock, some motoric and krautrock via the American South whatever it is it’ll be monumental! Charlie is a musician and graphic designer living in Knoxville, Tennessee. The Diamond Trip consists of the Electric Jeanni and Professor Husband, who play music and visuals. They say some influences include birds, grains, grass, ghosts and mirrors…

Another Knoxvillian, Jason Bowman, is the first person I ever knew who made music with a sliver mac. A musician, filmmaker and artist, he is amassing a warehouse of “library” music: incidental soundtracks for all your living pleasure. I’m always looking forward to hearing what he creates.

Mark Cannariato is an artist and sound maker from Brooklyn, NY. I first encountered him in the swamp hell that is Tampa Florida. All black rubber and wood assemblage. Imagine yourself in the last trek of Disneyland’s train ride through the primordial landscape. Giant mosquitoes buzz passed your head in the sweltering heat and the natives are restless… all set to a crazed beat created by the roar of the train.

I’ve yet to meet Maria or Dylan, a duo known as The Vaginals. I’ve yet to see them play live. They live about 3 hours away from me in the city of San Diego. I’m afraid that if they met me they would want to beat me up. They might be street tuffs with switchblades. Their music is categorized as danceable confrontation. I love it!

I haven’t seen it yet but I know you recently published a fourth issue… What can we expect from it?

More of the same quality artwork. Lots of new people are joining the troupe. I’m reaching out to woman. I think they are under appriacted in comics. Also woman musicians are playing a bigger part in the next few issues. The ugliness and hate of the current world political climate is also effecting my work. I’m hoping to voice some truth against these hateful bastards. Hopefully some of the other artists will voice their opinions as well.

To buy PopOok or for any info, you can visit the Facebook page or contact Hamo Bahnam through his Instagram account.

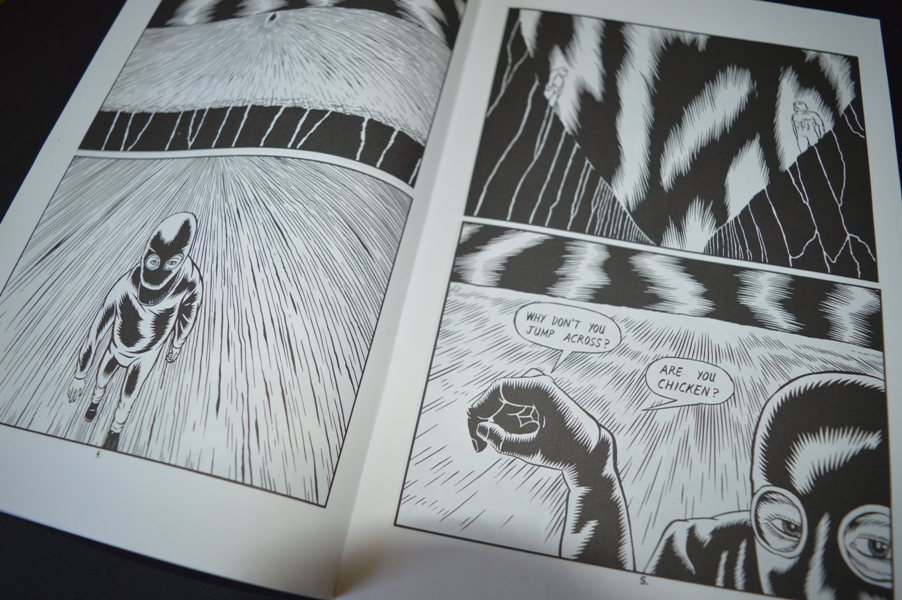

An afternoon with Steven Gilbert

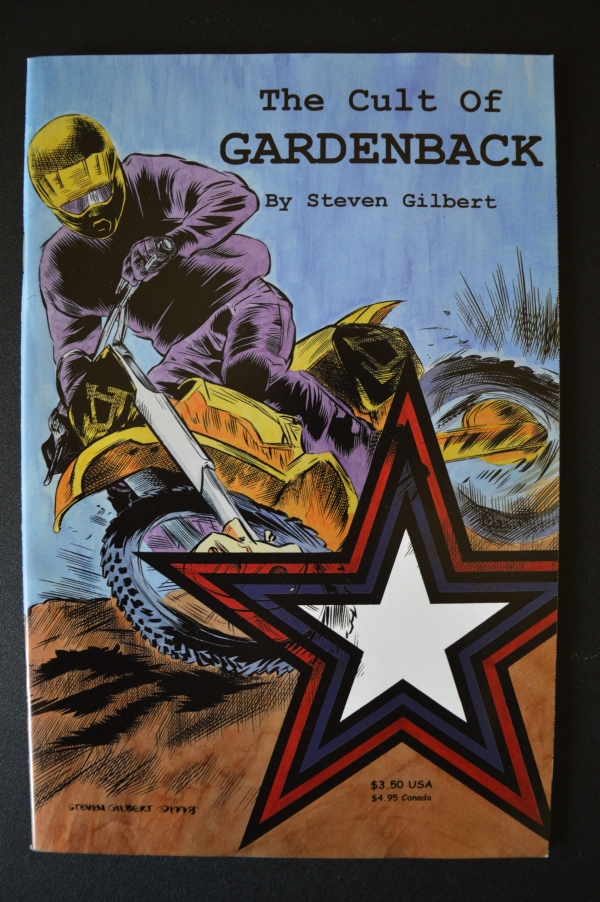

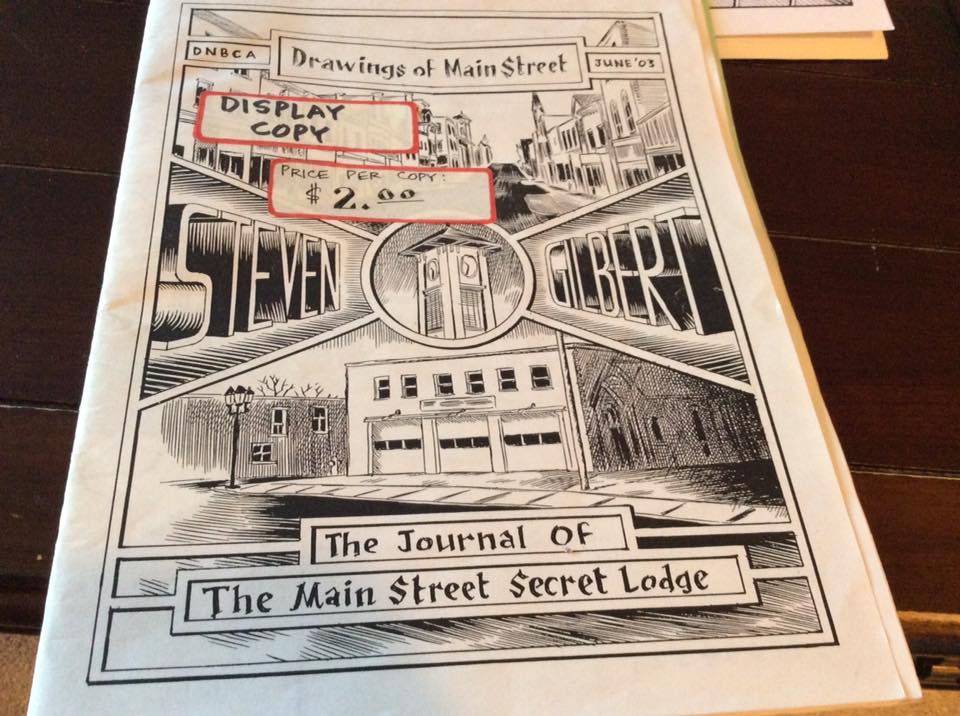

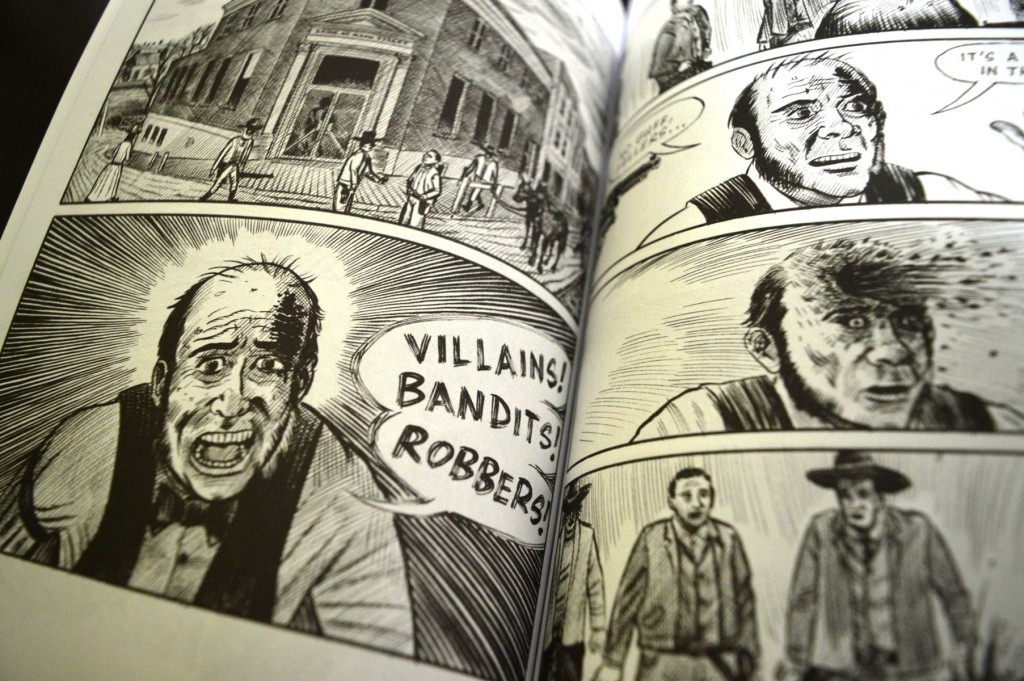

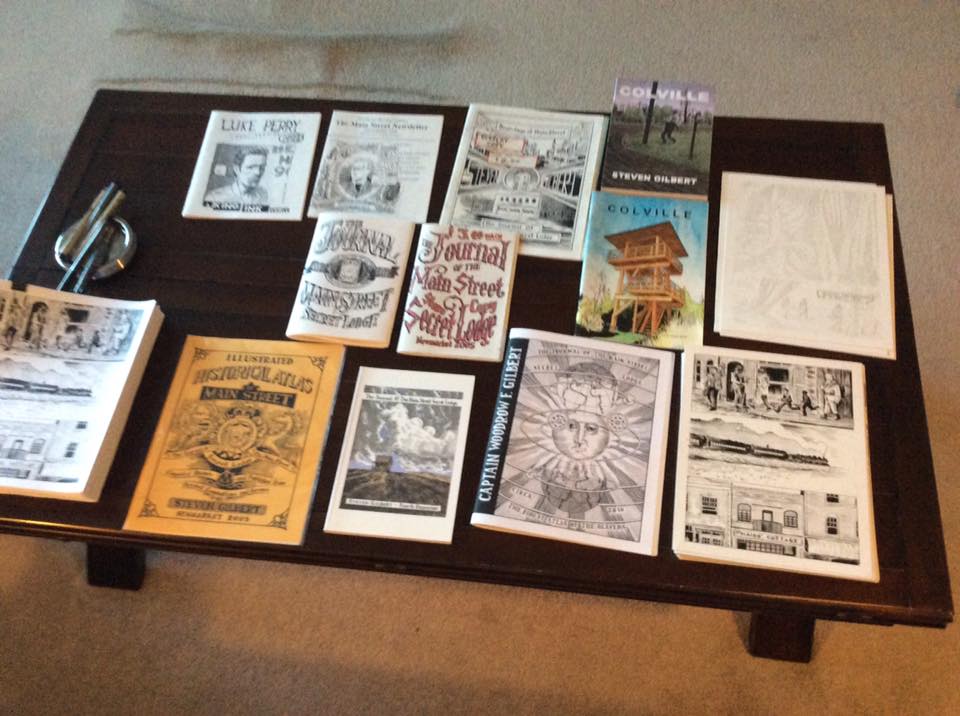

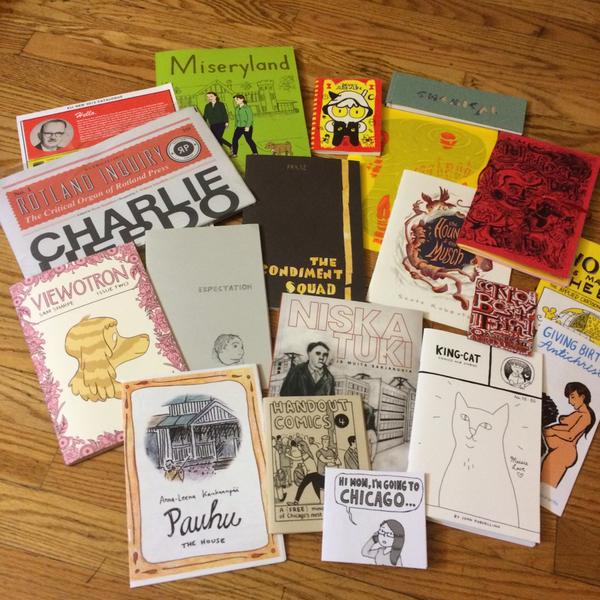

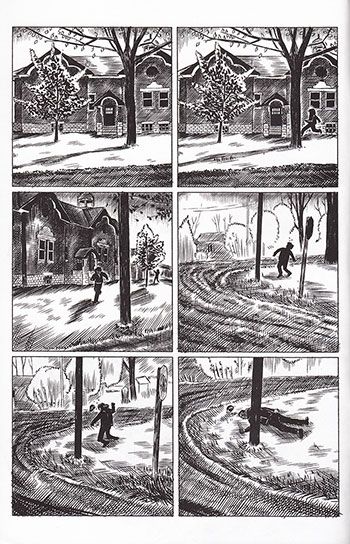

Steven Gilbert is a Canadian cartoonist author of The Journal of the Main Street Secret Lodge, a 2014 Dough Wright Awards winner, and of Colville. Back in the ’90s, he self-published six comic books of a series called I Had a Dream, plus two single issues, Gardenback and The Cult of Gardenback, where he developed the characters and the situations of the previous series. Between the two Gardenback comics, he published Colville, a 64-page comic book that received some good critics at the time. But after 1998 the world of comics lost Gilbert’s tracks and it was very difficult to find informations about him on the web until a few years ago. The most important source, if we can call it in this way, was a 2011 post at the Comics Comics website where Frank Santoro included “the guy who drew a comic from the mid-’90s called Colville” in a list of Good Cartoonists Gone. The same Gilbert contributed at the discussion writing this: “Wow, it’s nice to be remembered…I’m the guy who did the Colville comic. Glad you liked it Frank. I was an exhibitor at the SPX back in ’98 and sold a bunch of Colvilles there. I still draw comics when I can find the time, in fact, there is an entire second chapter of Colville completed (about 48 pages) plus about 25 penciled and lettered pages for a third chapter. Someday it’ll get finished and I’ll get a table at TCAF or sumthin’. Since 1999 I’ve owned and managed my own comics shop here in Newmarket, Ontario called Fourth Dimension. That takes up most of my non-sleeping time. Unfortunately, the drawing board has been back-burnered. I’m probably better at selling other peoples’ comics than I am at making my own!”. But Gilbert came back to comics in 2013 with a 128-page book, The Journal of the Main Street Secret Lodge, which won the Dough Wright Award for Best Spotlight Work the following year. And in 2015 he finally self-published, after nearly two decades in the making, the Colville book, including the original 64-page comic from 1997 and over one hundred pages of new material with the completion of the story.

I found out about Colville online and I was very curious about it for a long time, so when my friend Francesco (best known as the Italian cartoonist Ratigher) told me he had sent an e-mail to Mr. Gilbert ordering a copy of his books, I did the same and asked him if I could also sell Colville in my webshop. Ratigher wrote a review of Colville here at Just Indie Comics and from that moment a lot of people ordered the book or asked me about it. It was very funny to see a lot of Italian comic fans interested in a so obscure work, that it’s hard to find even in North America (Gilbert hasn’t a website and his books have no distribution at the moment). I exchanged some e-mails with Steven in the months after and when I went in Canada for this year’s TCAF I asked him to do an interview in Newmarket, a little town near Toronto where he lives and runs the comic shop Fourth Dimension, in 237 Main Street South. The interview took place on Monday 9th May at the presence of my friend Michele Nitri of Hollow Press and of Gilbert’s girlfriend Stacey.

Let’s start from the beginning. Are you born here in Newmarket?

I wasn’t born in Newmarket but I lived in Newmarket literally my entire life, my parents are resident in Newmarket and I always lived here.

And when did you start reading comics?

I was very young. My first recollection of comics is getting my hair cut at the barber and seeing this stack of Archie Comics and Disney Comics with the cover stripped off. But I had no affection for them at that time. When I was a kid I loved cartoons, I watched Bugs Bunny cartoons all the time. I was maybe more interested in animation at that very young age. When I was about 9 years old I had my tonsils removed at the hospital and my mom bought me a Spider-Man comic, that was kind of when I really became interested in comics.

Well, I read comics since I was very young but I was definitely hooked into them with a Spider-Man comic too, it was an issue with Doctor Octopus in the Bill Mantlo-Al Milgrom run.

Sure sure, Al Milgrom, yes… Mine was a Marvel Team-Up with Spider-Man and Doctor Strange.

Ok, and so when you started drawing?

As a young child, I remember drawing a lot before I was in the comics. I liked cartoons, so I doodled all the time. My dad used to bring home stacks of office paper, there was the letterhead on one side so I used the back of the sheets. I think at that age I was really into ninjas, I liked monster movies and I remember being obsessed by werewolves movies for quite a long time. I had tons of drawings with werewolves and monsters and stuff like that.

And this was still before comics?

Yes, and then when I discovered the comics I used to draw recreations of the cover artworks to try to figure out how that style worked. It was probably a little bit more when I was getting into twelve, thirteen, fourteen years of age that I started trying to make my own comics. When I was in high-school age I seriously started drawing comic books. My brother once wrote the script for a sequel to the Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, it was for a class project. And when I understood it would be about 30 pages I said “I won’t draw 30 pages for free”, so I charged him 200 dollars (laughs). I think my parents gave him the money to pay me, so they technically funded it.

Do you remember the story?

Oh no, it’s been a long time ago, in high school. I remember only I was trying to ink like John Totleben in Swamp Thing. It didn’t look like Frank Miller’s artwork, it looked like John Totleben from Swamp Thing. I should have the artworks somewhere at home but I never look at them and I don’t really want to look at them. The teacher made maybe a dozen of photocopies at the time and I’m petrified that somebody could have a copy of it. It was horrendously awful. Then I remember doing a comic book about the Travis Bickle character of Robert De Niro in Taxi Driver and then I drew another book with Grendel. My big dream at the time was that Matt Wagner could hire me to draw Grendel.

Were you a Matt Wagner’s fan?

Well, Grendel was a comic I read when I was fourteen-fifteen, and it was maybe the first step away from totally mainstream comics, because it was basically a super-hero comic but for grown-ups. The interesting thing is that Matt Wagner, who was a very skilled artist himself, was allowing other cartoonists to draw his character and so I thought “It can be my big chance”. I also thought to send my artworks to Matt Wagner but I never did it. My Grendel comic was a sort of remake of the movie Die Hard but with Grendel in it (laughs). I’m pretty sure the comic ended with the character blowing at the top of a building and it was totally ripped off from the end of Die Hard, I saw it like a month before and it was in my head.

And did you like also Sandman Mystery Theatre by Matt Wagner? It was one of my favorite comics back in the ’90s.

I actually read only a few pages of it, I knew at the time he was doing it because I worked in a comic shop but I never really read it. It was published in a period of my life when I didn’t read any Vertigo stuff, because alternative comics are the blast at the time for me.

So did you learn to draw by yourself, right? You didn’t take lessons or attended some school.

Well, in high school I had an art teacher who was very sympathetic to comics and encouraged me to do them. Well, he is in Colville, I drew this scene where there are my art teacher and my high school. He actually came into the store about two weeks ago, someone showed him the comic and he visited me specifically to say “Don’t put me in your comics anymore”. I think he was ok with the book until he arrived at the last 40 pages… However, in high school I was lucky to have an encouragement to draw comics but I didn’t get any specific instructions, I was purely absorbing from as many comics as I could, lots of copying and trying to figure how to put things on the page.

And what happened until I Had a Dream #1? You self-published it in June 1995 with your own imprint King Ing Empire but you created comics even before I guess, so I’m curious if you made something before that issue.

I tried several times to get a comic put together. I was in my mid-twenties when I published the first issue of I Had a Dream, so it was a lot of time after high school. In the meantime, I worked at a comic store and I also drew comics.

But only for yourself.

Yes, it was my training ground, I drew hundreds of pages of comics and illustrations but I never showed them to anybody, maybe just at few friends. There was a couple of crime comics I worked on, a sort of murder mystery stories I was trying to figure out how to develop and at a certain point the actual events that inspired Colville occurred and I immediately thought “This is the story I want to do”.

And this is before I Had a Dream.

Yes, it was long before I Had a Dream but I already drew a cover for that story, even if it was a different cover both from the one of the Colville comic book than from the one of the Colville graphic novel, but more similar to the latter. At the time I thought the comic should be called Warning Shot but I had this intuition I wasn’t still good enough to do the story I had in my head, because at the time I never drew a comic that was more than 25 pages. I needed to figure out how a comic book works. So, it happened that a friend of mine, one I knew from years without really knowing he drew comics, came in the comic shop…

What was his name?

His name is Jason Williams.

Ah ok, I thought he was him, his name recurs in your first comic books.

Yes, so he came in the shop and showed me a Spider-Man comic he drew, and maybe it was the worst comic I did ever see. It showed me also a rejection letter from Marvel. Then, he started drawing a comic called Underterra and he wanted to publish it but he wasn’t really ready to publish a comic. He also gave me the pages of the first issue asking me to edit them. I read it and it was full of mistakes, so I wrote a lot of notes and at a certain point I begged him to redraw it, proposing to co-write and ink but at the end he published the first Underterra how it was, with all the mistakes. And he printed five thousand copies per issue, distributing all the six issues with Diamond. But I think he sold only 90 copies each.

So, was that an inspiration for you? (laughs)

Well, what I got from him basically was… the name of his printer (laughs). He gave me this contact information and so I made the decision “If this guy can do a comic, I better get off my ass and do a comic”. I already had the first versions of the first three issues of I Had a Dream drew very rough because I made them like 24-hours comics. So I completely redrew them. Looking back, now I’m not satisfied with the results and probably I shouldn’t have published them but at the time they helped me learning cartooning. However I think there is a big shift in the fourth, fifth and sixth, I managed to put my ideas on the pages, the artworks got better. But with those sixth issues I felt I was done with that, I thought I was ready to do the Colville comic. But then I drew a really big picture for a friend of mine as a birthday present and it was a very big comic with like 40 panels. That became the first Gardenback comic and I published it before Colville.

But looking still at the first three issues of I Had a Dream, these follow the same patterns of the newspaper strips, there are these two “guys” in another dimension who face each other, with a lot of situations which can remind Krazy Kat or some cartoons.

I’m sure Krazy Kat didn’t have any kind of influence on me at the time, but as I said before I loved the Warner Brothers-Looney Tunes stuff, just absurd violence, things crashing together, walls being knocked down and so on… They surely influenced me. You know, the firsts I Had a Dream were very nonsensical, I was a huge Chester Brown fan and I remember reading an interview where he talked about his process of doing comics and he said he drew panel after panel, without having a precise idea of the whole…

Yes, like in Ed The Happy Clown…

Exactly, so I worked in that way too.

Then with I Had a Dream #4 you started Slipstream, a very different two-part storyline about Roswell, psychological operations, Russians, conspiracy theories. Did you plan it from the beginning?

Absolutely not. I was probably watching some X-Files episodes and reading about the Kennedy assassination, I read about 40-50 books about it. I was obsessed by conspiracy theories in my twenties, these things took a lot of my attention at the time and comics in some way are what got me out of interest. After doing those comics I never got interested anymore. That was the end of it for me.

Between Gardenback and The Cult of Gardenback you published the first issue of Colville, right? It should be from 1997…

Yes, in the beginning it should have been much smaller, like 25 pages, and it had to be only about the confrontation in the schoolyard. It was loosely based on a true crime story, I clipped the newspaper article when it was happening because I remember reading it and thinking “It could be an interesting comic”. But those were just the bare bones, the story began to grow around the episode of the shooting in the schoolyard. I thought to do a 64-pages comic and I had the bones of the story and a lot of the imagery was in my head. I went up to Keswick, a small town 20 minutes up the highway from Newmarket where the facts actually occurred. My friend Jason Williams lived there, so he knew all the neighborhoods. We drove there one day and took photo references I used for the comic.

Do you use a lot of photo references, right?

Yes, these researches are part of my methodology, because I don’t write scripts…

Never?

I tried but I never successfully wrote one, when I finish and read a traditional script with panel descriptions, dialogues and so on, usually the ideas just seem stupid and I can’t use them. The only way I can make comics is to sit down and draw. My process of writing is the creation of the comic.

The 64 pages of the Colville comic book from 1997 are exactly the first pages of the 2015 book or you changed something?

Yes, the first 64 pages of the graphic novel are the same of the comic book, except for maybe one or two extremely tiny revisions of the artworks.

That comic book was really different from I Had a Dream. There is a new feeling in it, like the inspiration came more from the movies than from other comics or conspiracy theories. I can feel the mood of some American movies from the ’70s or the early ’80s, I think to Brian De Palma, Martin Scorsese or also David Lynch of Blue Velvet.

I usually deny any influence and I don’t think for cartoonists is a good idea to look at cinematic references, because comics are their own thing. But, having said that, at that time I was a huge fan of David Lynch and of the Blue Velvet movie in particular, that was a small town perverted crime story. I was also a big fan of the Twin Peaks tv show and I can tell you a little trivia about that. I decided on the title Colville from the Canadian painter Alex Colville, even if there isn’t really any direct visual correlation to the comic, it was more about the mood and the atmosphere. But there is a scene in the Twin Peaks tv show where they’re describing the geography of where Twin Peaks is and – it’s been a long time since I watched it but the line of dialogue should say “In the North-East corner of Washington state right on the border with Montana and just below the Canadian border”. And for some reason, I decided to get out a map to look at what’s there and there is a town called Colville. You can look at a map, it isn’t a joke. This was after the Colville comic book was drawn, so I thought “Well, the force of the universe are working together…” (laughs). This is about the Lynchian influence, about Brian De Palma, well, I co-dedicated the graphic novel to Brian De Palma and Nick Cave, and the first is largely for the use of the tracking shot in his movies. I’m a bit of a sucker for tracking shots when I’m watching the movies… The second chapter of the book begins with the character recording with the video camera, so you can read the entire chapter as a long tracking shot, as if the camera never leaves.

I usually deny any influence and I don’t think for cartoonists is a good idea to look at cinematic references, because comics are their own thing. But, having said that, at that time I was a huge fan of David Lynch and of the Blue Velvet movie in particular, that was a small town perverted crime story. I was also a big fan of the Twin Peaks tv show and I can tell you a little trivia about that. I decided on the title Colville from the Canadian painter Alex Colville, even if there isn’t really any direct visual correlation to the comic, it was more about the mood and the atmosphere. But there is a scene in the Twin Peaks tv show where they’re describing the geography of where Twin Peaks is and – it’s been a long time since I watched it but the line of dialogue should say “In the North-East corner of Washington state right on the border with Montana and just below the Canadian border”. And for some reason, I decided to get out a map to look at what’s there and there is a town called Colville. You can look at a map, it isn’t a joke. This was after the Colville comic book was drawn, so I thought “Well, the force of the universe are working together…” (laughs). This is about the Lynchian influence, about Brian De Palma, well, I co-dedicated the graphic novel to Brian De Palma and Nick Cave, and the first is largely for the use of the tracking shot in his movies. I’m a bit of a sucker for tracking shots when I’m watching the movies… The second chapter of the book begins with the character recording with the video camera, so you can read the entire chapter as a long tracking shot, as if the camera never leaves.

Ok, we’ll say more about Colville later, when we’ll arrive to present days. Now I’d like to talk about your long pause if it isn’t a problem. In less than three years, from June 1995 to April 1998, you published 6 issues of I Had a Dream, Gardenback, the first issue of Colville and The Cult of Gardenback. Then between April 1998 and 2013…

Nothing!

Yes, exactly (laughs). Nothing until The Journal of the Main Street Secret Lodge came out in 2013. Fifteen years is a long break.

When I finished the 64 pages of the Colville comic book, I realized that there was room for a couple of more connections. Initially I saw Colville as a 64-pages story with completion and nothing more, but as I was maybe about two-third of the way through I started thinking about it as the first chapter of something larger. But I had also an attachment to the Gardenback comics and I got this idea I should rotate between the two and each year I would do one or the other. So I drew and self-published The Cult of Gardenback in 1998, it was a pretty quick process to draw a comic, then self-publish and sell it through Diamond…

Did you use Diamond since the first issue of I Had a Dream, right? And also Capital City Comics at the time.

Yes, at the beginning I was distributed also through Capital City but then Diamond swallowed everyone up. However, after The Cult of Gardenback was published, I started working at the second chapter of Colville. My plan was that my next book would be Colville #2. In the meantime I was working at a comic book store, The Comic Wizard here in Newmarket, just across the road from where we sit now. Yes, my whole life is in this corner basically (laughs)… As I was working there, the store changed ownership but I continued to work in the shop. The manager bought it in December of 1996 but the business was failing and the store wasn’t doing very well. He owned the store for a couple of years and he struggled to keep it alive. At a certain point I thought to buy the store but then I realized it wasn’t possible. So, I was going to be out of job and I had absolutely no marketable skills to work in the real world. The only thing I ever did at that point was selling comic books, so I decided to open my comic shop.

So, did you open Fourth Dimension after The Comic Wizard closed?

Well, it was basically at the same time. At one point it was clear that the comic shop was closing in two weeks, so I immediately signed a lease on my store and called distributors to set up accounts and everything. But the owner of The Comic Wizard attempted to keep things going and so there was actually a very weird time where I opened my store but he was still open trying to liquidate.

So, there were two comic shops? (laughs)

Yeah, within a block, in the same street. But one was closing and I was just getting things started… What happened with cartooning, well, I never worked that hard in my life, opening a business was just insane because I was doing it on my own. My plan was to put the comics aside for six months and then get back to them. But the store was so much hard work, at the end of the day I was exhausted and I couldn’t work on comics when I was at home. That period of six months turned in two years and then three, four, five… I remember pulling out those unfinished pages with the intention of completing the book but I looked at them with my pencil for twenty minutes without drawing a single line and then I put them away. And then a year would go by before I tried again. It happened in 1999, 2000, 2001 and continued for several years. I still did some drawings and caricatures of customers in the store purely for my own enjoyment, but not comics.

And landscapes? There are a lot of landscapes in The Journal of the Main Street Secret Lodge book, did you work at them in those years?

No, no landscapes. I don’t even know, they were mostly wasted drawings. At a certain point I remember having the realization “I’m not a cartoonist anymore, it’s a long time since I’ve done a comic”. But then, after some years, I did start drawing seriously again, when I invented the fanzine Journal of The Main Street Secret Lodge. It was about 2003 when I self-published one of them, just for fun, to give it to friends and customers. Maybe I photocopied a couple of them even before, they were a sort of merchant newsletters. I was interested in the historical side of Main Street, the buildings, and the atmosphere. I started to do it fairly regular, creating little stories about Captain Woodrow Gilbert and his adventures, following more or less the same formulary, usually bad guys coming in Newmarket to rob the bank and Woodrow going to fight and kill them. It was totally for my own amusement. They started to become more and more ambitious, I changed format, some were published like digest size, some had 24 pages, then 36, some 48…

How many of these zines did you publish?

I think I did five or six of them after the one of 2003. The last one was still photocopied but it had 84 pages and I took about a year to finish it. It had a ton of illustrations and a long hand-lettered short story. It was just pure insanity to do that and just photocopy. When one of my customers who used to write comics himself back in the ’80s read it, he came in the store and he gave me a three-pages letter that basically said “You’re an idiot for not doing comics because this is great but it’s not what you should be doing” (laughs). And I just laughed, because these zines were purely for my own self, I didn’t care about people reading it, I produced them only for my satisfaction, to do something creative. But I think at that point I did have the idea for The Journal of the Main Street Secret Lodge. Actually it was an idea that has been in my mind since while I was working on Colville, I thought at this western bank robbery story using Newmarket as the backdrop. And it sat there in my head for years. Then, it happened I found out that article on the website Comics Comics, probably I saw the link on another website I was on, because at the time I didn’t use so much the web, I never googled anything I guess (laughs).

So, did you know the Comics Comics website?

No, I had never seen that website before. The only thing I knew was that Comics Comics was a print publication, they did a couple of magazines I had in the store but sold out before I even read them. I didn’t know Frank Santoro was involved with them at all, I knew Santoro for his comics like Storeyville that I was a big fan of. However, I think I saw it on Heidi MacDonald’s page, The Comics Beat, there was this link saying something like “Frank Santoro at Comics Comics has an article about cartoonists from the ’90s gone”. I remember I had the mouse cursor over that on the screen thinking “If my name is on that list I’ll shit my pants”. And I clicked on it and I found “The guy who did Colville“. So, I thought “Shit, I’m on this list and that means someone remembers my comics”. And I just knew, it was like a light switch going off in my head saying “You’ve to do another comic book”. So, I immediately started working on The Journal of the Main Street Secret Lodge.

It was 2011, right?

I think so, I’m not so good at archiving things in my mind. However, I started drawing with the idea to do another photocopied zine. The previous one consisted of 21 pieces of paper put together, stapled and then folded to make 84 pages, plus the cover. I had to staple some zines three times and it really pissed me off. So I thought 84 pages were the limit and while working on the Journal I paid attention to the pages and as I got to 70, then 75, 80 and so on, I started worrying. And when I finally finished it and it was 130 pages, I showed the work to my friend Eddie and he told me “This has to be a book, it can’t be just some photocopy bullshit you put near the counter giving away to people who enter the shop”.

Did you think to propose it to a publisher or did you want to self-publish it from the beginning?

I never really thought about sending it to anyone, self-publishing was really my only idea at the time. I thought of something like print on demand or at a very small print run, because I was selling a hundred of the photocopied zines, so I thought I would need a hundred copies even this time. I did a lot of researches about print on demand but when I talked to some people at comics conventions everybody seemed not satisfied with the resulting product, they talked about problems with the binding, the glue and so on. While I was doing these researches on printing, I found somewhere the name of the printer I dealt with 15 years earlier and I thought for the first time to do a proper offset printing. I contacted the same guy I talked 15 years before but I found an old e-mail because somewhere along the line he changed printing company, but he was looking at this old e-mail once in a while and e-mailed me back. Well, I don’t know where I’m going with this answer…

Well, I think this is the point when you decided to do it in offset.

Yeah! (laughs). Well, I think a big fact was the affordability because printing in offset the minimum was typically a thousand copies, you know, it’s a bit more an investment doing that financially that a hundred print on demand copies. But I found out that the costs of print on demand were really high. It was 9 dollars per copy, plus 2 dollars to ship to Canada since it was a USA printer, so I had to pay 11 dollars per copy, plus the exchange rate while to do one thousand copies in offset I would need 2200 Canadian dollars. It was a really good deal. So, that was the point when I said “Ok, I’m going to print it, for real”.

That book won the Dough Wright Award for Best Spotlight Work, right?

Yes, things went a little bit crazy, because initially I was just selling it only on the counter here in the store. I had plans to go to TCAF the following year but I didn’t have any thoughts of submitting the book for consideration for Dough Wright Awards. Then a friend of mine, who lives in Winnipeg, had a copy of the book and told me there would be a Chester Brown signing there in a couple of days and I said him “Damn, I’d love to give Chester a copy of the book, but I couldn’t send you one in time” and he said “Well, I’ll give him my copy and you can send me another one”. So he gave a copy to Chester and he e-mailed me “Oh, Chester was so happy to hear you made a new comic”.

You already met Chester Brown at that point, I guess.

Yes, I knew Chester very formally and casually at signings and talked to him. He knew my comics from the ’90s too. I don’t know how many time passed but one day I had this phone call from Chester at the store and he was very complimentary about the comic. And he said he was on the nomination committee of the Dough Wright Awards and he asked me to submit The Journal sending five copies to the members of the committee. He even joked that he tried to buy some copies at The Beguiling in Toronto but they didn’t have it and they didn’t know how to get. I said “I know how to get copies, I’ve boxes full of them” (laughs).

So at that point you hadn’t even sent copies to The Beguiling.

No, I actually called Peter of The Beguiling right after that and I asked if he wanted some copies and he said “Yes”. When the nominations for the Dough Wright Awards came out, it was 2014, my name was on the list with some pretty awesome cartoonists. And it was very very weird to me, there was a lot of disbelief that I had my name written down with those other cartoonists. Well, you know, the Dough Wright Awards people invite you to the party at TCAF because you’re nominated and I said “Well, it would be probably bad form to not be there when you’re nominated and you’re exhibiting at the show”. And they reserve seats for you like in the front row in a sort of VIP section, but even on the day of the awards I wanted to seat in the back because I figured that it could be an easy escape afterwards. We went there with Stacey but we sat midway, we didn’t sit in the VIP section, I didn’t feel it was appropriate for whatever reason…

You found a compromise…

Yeah yeah, midway back. Then, it seemed pretty surreal to me what was going on. The category I was nominated for, there were four other cartoonists that I think they are amazing, there were Dakota McFadzean, Connor Willumsen and… Oh man, I’m drawing a blank on…

But the category Best Spotlight Work was for young cartoonists, right? (laughs)

Yes, it was for upcoming cartoonists, which was a little bit of a joke, I found it was kinda funny. But if you watch the page of the awards, there is no age specify, the category is for emerging cartoonists but they don’t have to be young. I don’t’ really have any nerves about this nomination until I was there, then it was really terrible. In the days before the awards, Stacey looked at me and told me “You’re gonna win” but this seemed totally impossible to me. But she knew it.