Al via i pre-order di Just Indie Comics

Dopo il Just Indie Comics Buyers Club arriva un’altra iniziativa che sfrutta le logiche del “gruppo d’acquisto” per far arrivare in Italia fumetti ancora più difficili da trovare, poco conosciuti, spesso autoprodotti o comunque pubblicati da piccolissime realtà editoriali. Si tratta dei pre-order di Just Indie Comics, che se tutto va bene troverete di tanto in tanto sul webshop. Il funzionamento è banale ma lo spiego per evitare fraintendimenti: prima di far arrivare questi fumetti dall’estero, sarà disponibile soltanto per qualche giorno una prenotazione (in questo caso fino al 22 gennaio). Finita la scadenza prefissata, verrà fatto l’ordine al fumettista, editore o distributore di turno per il numero di copie che sono state prenotate. Chi ha pre-ordinato questi fumetti li potrà leggere dopo qualche settimana: pagherà prima ma almeno avrà la sicurezza di ricevere albi ancor più rari e spesso più bizzarri di quelli ospitati abitualmente nel webshop. Mi sembra un’iniziativa quasi necessaria nel momento in cui parecchi degli autori che si trovavano all’inizio nel negozio di Just Indie Comics sono ormai stati pubblicati dalle case editrici nord-americane e sono accessibili a tutti, persino su Amazon. Qualcuno è stato addirittura tradotto in italiano. Ecco dunque che bisogna guardare oltre, alla ricerca non della prossima next big thing ma di una diversità stilistica che nasca da un’ispirazione autentica e non dalla semplice voglia di essere “alternativo”.

Si comincia con quattro fumetti provenienti dal sito Domino Books, casa editrice e distro curata dal fumettista/editore/critico Austin English. Della Domino si è parlato qui più volte, anche e soprattutto in occasione del Buyers Club. E infatti due dei fumetti in pre-order sono di autori già noti agli abbonati degli scorsi anni. Di Ian Sundahl, di cui gli abbonati 2017 hanno ricevuto il “best of” The Social Discipline Reader pubblicato proprio da Domino, arriva questa volta Social Discipline #10, nuovo numero della sua fanzine uscito alla fine dello scorso anno. Per qualche parola in più su Sundahl vi rimando a questo post.

Altra autrice di cui ho parlato più volte su Just Indie Comics è E.A. Bethea, il cui Book of Daze, ancora edito da Domino, è stato spedito agli abbonati 2018. La Bethea fa fumetti-non fumetti davvero unici, tanto che si potrebbe parlare di poesia illustrata. Come Sundahl, anche lei è un’artista completamente fuori dal coro, che non ha rapporti con il resto della scena, né un interesse particolare per il medium, scelto semplicemente come mezzo di espressione e piegato alle proprie esigenze. Per saperne di più vi rimando a questo breve focus su Book of Daze e alla rubrica Comics People che le dedicai qualche anno fa sul blog. E vi segnalo anche che qualche giorno fa su The Comics Journal Rob Clough ha recensito le produzioni più recenti della Bethea, tra cui l’autoprodotto All Killer No Filler ora disponibile in pre-order.

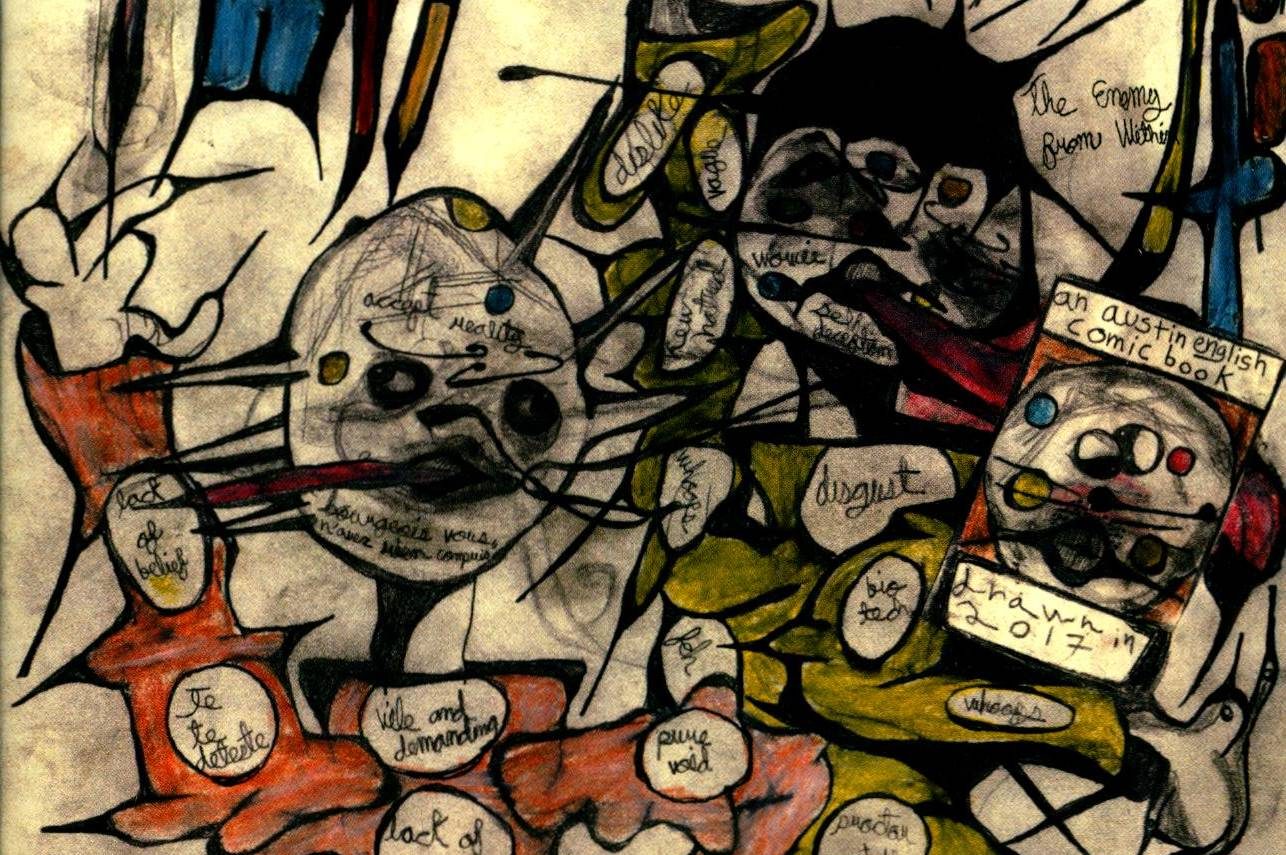

Arriviamo così a The Enemy From Within dello stesso Austin English, altra decostruzione espressionista dell’idea di fumetto, con la narrazione astratta tipica delle sue storie (si vedano quelle riunite in Gulag Casual, di cui avevo scritto qui) che lascia spazio a digressioni esistenzialiste nel racconto che dà il titolo all’albo, a mio parere uno dei suoi vertici grafici. Completano l’albetto Half-hearted Slogan Dance, danza in bianco e nero al ritmo di frasi fatte e luoghi comuni, e la mute evoluzioni del protagonista di Solo Dance #2.

Five Perennial Virtues #2 di David Tea è invece un albetto “misterioso” di qualche anno fa ristampato lo scorso anno con contenuti aggiuntivi: per me una delle sorprese migliori del 2018. Ne avevo parlato brevemente in questo report dal Cake di Chicago.

Spero di avervi abbastanza incuriosito, se non vi sono bastati i link potete cliccare su PRE-ORDER per dare un’occhiata a tutti e quattro i fumetti di cui si è parlato sin qui. E vi ricordo che per prenotarli c’è tempo fino al 22 gennaio.

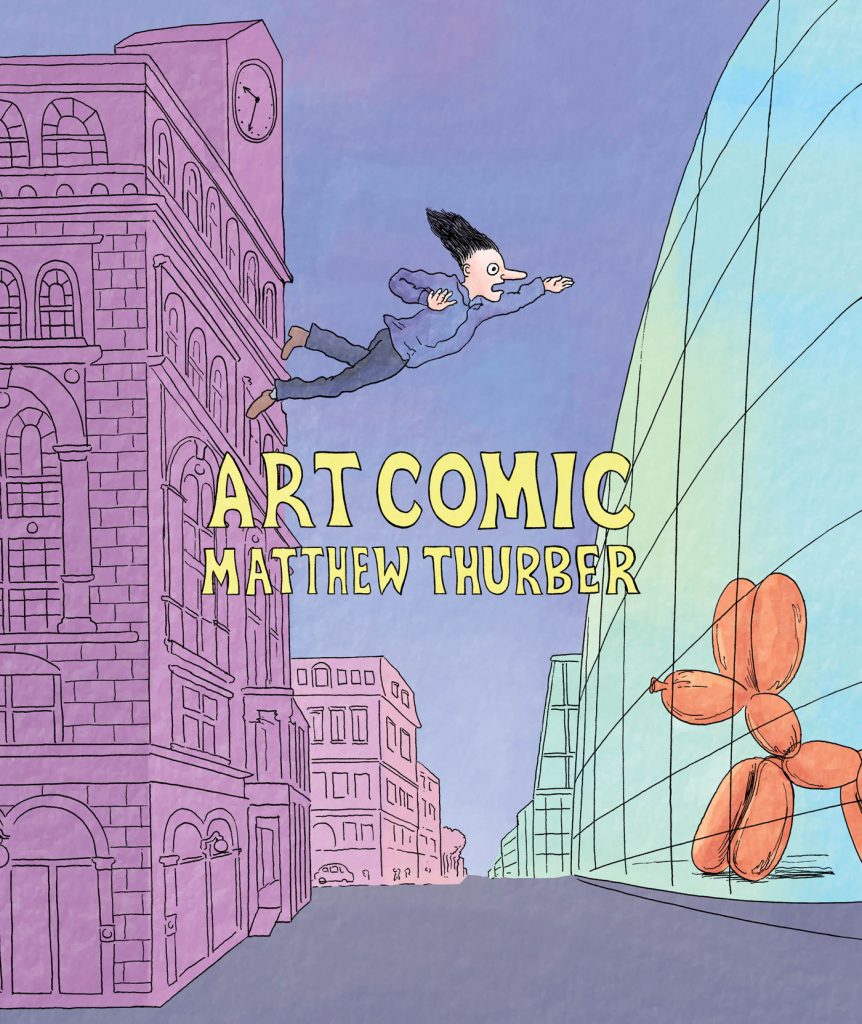

“Art Comic” by Matthew Thurber

Matthew Thurber is one of the most brilliant, crazy, stimulating, classic, experimental and funny cartoonists around. Or maybe it’s the only one who sums up all these features in one go. His 1-800-Mice, first published in comic books and then in a 2011 hardcover collection by PictureBox, was inspired from the Fort Thunder scene for the pseudo-fantasy setting – still the citadel typical of Brinkman, Chippendale & co. – but mixed it with a lot of film and literary references: first of all Thomas Pynchon, from whom Thurber takes over his obsession with secret societies, religious cults and conspiracies about which little or nothing the common man (and so the reader) can understand. The following Infomaniacs remains to this day, despite being from 2013, the most accurate essay in comic form on our digital existence. Serialized as a web-comic and then collected by PictureBox, the comic explained how the Internet has become more real than reality with a classic style – most of the pages are four panels – and without looking for far-fetched stylistic innovations that often in many comics of today, copied once on Tumblr and now on Instagram from the copy of the copy of the copy, are only empty form and no substance.

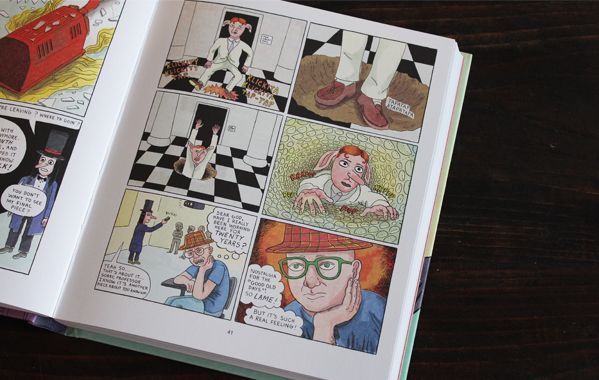

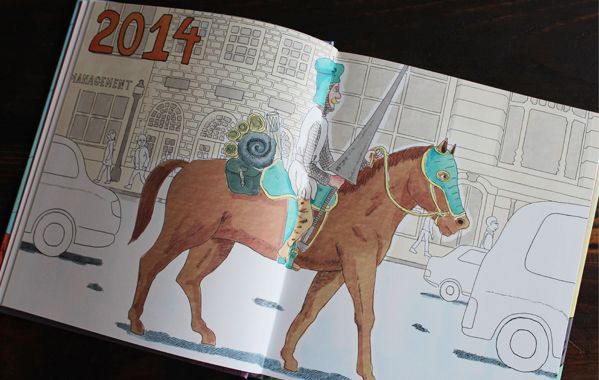

Thurber’s comics are extremely complex, yet there is always a moment when the character looks into the eyes of the reader and asks the simplest question. In Art Comic – now a full-color hardcover book out for Drawn & Quarterly after being serialized in five black and white comic books by Swimmers Group between 2014 and 2017 – the main character Cupcake asks: “Is it possible to become a great artist without turning into an asshole?”. This is a serious issue, and it’s also one of the many topics of the book. Another one is if art can still be revolutionary in a system where a single piece is worth even hundreds of thousands of dollars and where art schools are only accessible to rich people. Thurber also examines the age-old problem of what it’s art and what is not, starting from the Dadaists’ ready-made, here called “a tool of magical wealth generation” able to turn “shit into gold”, to get to Matthew Barney, with whom Thurber’s satire unleashes at the point of sadism. All serious issues taken sideways, from the beginning, from the bottom, from behind, and always with an infectious sense of humor. Just think of the first chapter of the book, where Thurber, in a sort of automatic writing trance, introduces as usual several characters, settings and in this case even time plans. So we meet Cupcake, a student of Cooper Union in 1999 (Thurber’s own college) and a big fan of Matthew Barney, only interested in creating works with references to the creative universe of the “master”. Among his colleagues, all students of the creepy Professor Password (former a Robert Rauschenberg’s disciple), stand out the promising Russian Boris Snegovoi and Tiffany Clydesdale, a Christian student who makes only works about faith. Meanwhile, the crew of the television show Drunk T.V. and a group of pigs called Free Little Pigs make a mess at the opening of Damien Hirst’s exhibition. And so we are in 2014, where a former student of Cooper calls himself Ivanhoe and rides a horse dressed in armor, followed by an intern hired for a mysterious mission. While 2014’s Tiffany summons Jesus with a prayer/work of art, in Miami a duo of bodyguards working for Zobchik, an alien from planet Qaxb, is bringing to Art Basel two robots having sex with the aim of getting the lady-robot pregnant in time for the fair. And this is only the first part. Among the various and absurd situations of the following chapters, we can’t forget the appearance of the Group, a secret society that boycotts the emerging artists through art schools, led by a certain R. Mutt, whose name could sound familiar to most of you…

The many storylines sometimes alternate with clear cuts, others converge into one another, or are resumed after pages, cross completely, only partially, not at all, and it isn’t important if something remains unresolved, unclear, vague: after all who are we to understand eveything of the silly complexity that surrounds us? It’s easier to be carried away, stunned by the flow of ideas and by the whirlwind of gags that follow each other relentlessly, while we laugh almost at every page and make our way through references to artists, groups and art movements of the last hundred and a half years, in a system of special guests and flashbacks that intertwines with narration without ever being an end in itself. Art Comic comes out for the same publisher and in the same year of Sabrina but represents its complete opposite. While in Drnaso the characters seem deliberately emotionless, nearly without facial expressions, in Thurber they look caricatural, exaggerated, hilarious and beatifully designed one by one. While Drnaso regulates everything through an obsessive logic, Thurber gives rise to an unbridled explosion of creativity: he is deeply interested in building a narrative but he likes to develop a loose structure, so that his book looks totally different from the usual “graphic novel” people are used to see in bookstores today.

Thurber’s endings are often sudden, almost cut off, and never definitive, as in the tradition of post-modern literature. In the comic book edition of Art Comic, Cupcake figured out – after an encounter with Mr. Colostomy, the talking horse recurring in every Thurber’s comic – how to turn a toilet bowl into gold, finding members of Gelatin art group inside it. When they invite Cupcake to join them, he dives into the toilet, as in Trainspotting via the Atalante by Jean Vigo. Put at the end of Art Comic #5, this was an unexpected ending, even for Thurber, since a lot of narrative threads remained totally unsolved. I spent months wondering (while I was also thinking about something else, of course) if it was really over and so it was a pleasant surprise to discover a never-seen-before sixth chapter of 33 pages, which leads to the conclusion (or almost) of the story. In the book you’ll find even some new “special contents”, i.e. 6 pages in which the characters and Thurber himself reflect on the story we’ve just finished to read. Instead we can’t find in the book the beautiful essay/editorial written by Thurber for the fourth issue of the series on the theme of the mystifying historicization of art. But these are minor details for those who haven’t still read Art Comic and, if you are among them, you’ve to do it as soon as possible. As expected, it is absolutely my best of 2018, without competitors.