Matthew Thurber is one of the most brilliant, crazy, stimulating, classic, experimental and funny cartoonists around. Or maybe it’s the only one who sums up all these features in one go. His 1-800-Mice, first published in comic books and then in a 2011 hardcover collection by PictureBox, was inspired from the Fort Thunder scene for the pseudo-fantasy setting – still the citadel typical of Brinkman, Chippendale & co. – but mixed it with a lot of film and literary references: first of all Thomas Pynchon, from whom Thurber takes over his obsession with secret societies, religious cults and conspiracies about which little or nothing the common man (and so the reader) can understand. The following Infomaniacs remains to this day, despite being from 2013, the most accurate essay in comic form on our digital existence. Serialized as a web-comic and then collected by PictureBox, the comic explained how the Internet has become more real than reality with a classic style – most of the pages are four panels – and without looking for far-fetched stylistic innovations that often in many comics of today, copied once on Tumblr and now on Instagram from the copy of the copy of the copy, are only empty form and no substance.

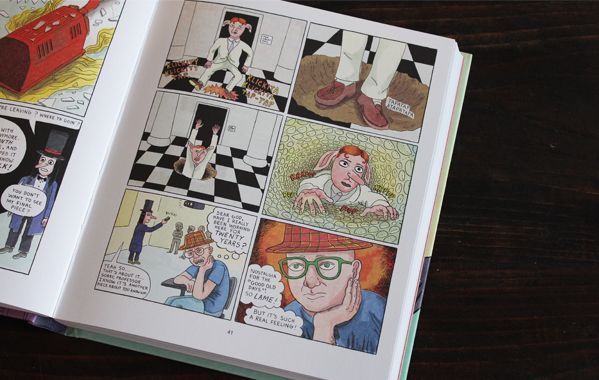

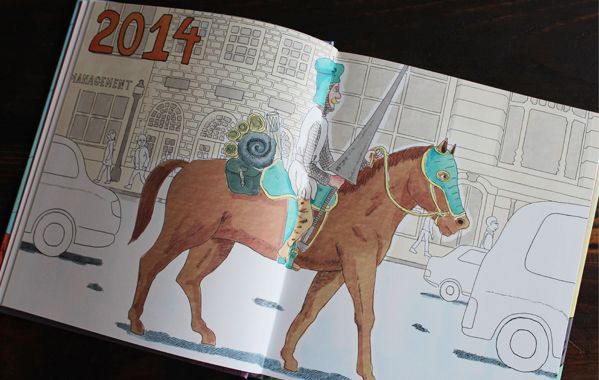

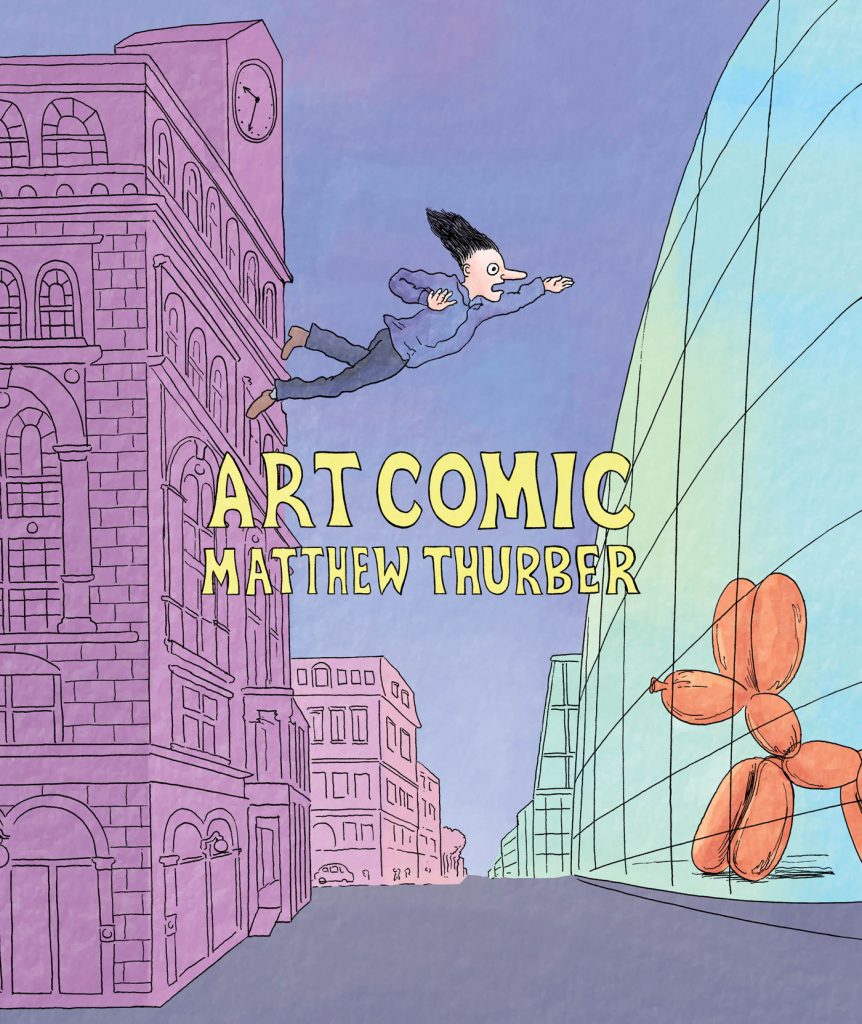

Thurber’s comics are extremely complex, yet there is always a moment when the character looks into the eyes of the reader and asks the simplest question. In Art Comic – now a full-color hardcover book out for Drawn & Quarterly after being serialized in five black and white comic books by Swimmers Group between 2014 and 2017 – the main character Cupcake asks: “Is it possible to become a great artist without turning into an asshole?”. This is a serious issue, and it’s also one of the many topics of the book. Another one is if art can still be revolutionary in a system where a single piece is worth even hundreds of thousands of dollars and where art schools are only accessible to rich people. Thurber also examines the age-old problem of what it’s art and what is not, starting from the Dadaists’ ready-made, here called “a tool of magical wealth generation” able to turn “shit into gold”, to get to Matthew Barney, with whom Thurber’s satire unleashes at the point of sadism. All serious issues taken sideways, from the beginning, from the bottom, from behind, and always with an infectious sense of humor. Just think of the first chapter of the book, where Thurber, in a sort of automatic writing trance, introduces as usual several characters, settings and in this case even time plans. So we meet Cupcake, a student of Cooper Union in 1999 (Thurber’s own college) and a big fan of Matthew Barney, only interested in creating works with references to the creative universe of the “master”. Among his colleagues, all students of the creepy Professor Password (former a Robert Rauschenberg’s disciple), stand out the promising Russian Boris Snegovoi and Tiffany Clydesdale, a Christian student who makes only works about faith. Meanwhile, the crew of the television show Drunk T.V. and a group of pigs called Free Little Pigs make a mess at the opening of Damien Hirst’s exhibition. And so we are in 2014, where a former student of Cooper calls himself Ivanhoe and rides a horse dressed in armor, followed by an intern hired for a mysterious mission. While 2014’s Tiffany summons Jesus with a prayer/work of art, in Miami a duo of bodyguards working for Zobchik, an alien from planet Qaxb, is bringing to Art Basel two robots having sex with the aim of getting the lady-robot pregnant in time for the fair. And this is only the first part. Among the various and absurd situations of the following chapters, we can’t forget the appearance of the Group, a secret society that boycotts the emerging artists through art schools, led by a certain R. Mutt, whose name could sound familiar to most of you…

The many storylines sometimes alternate with clear cuts, others converge into one another, or are resumed after pages, cross completely, only partially, not at all, and it isn’t important if something remains unresolved, unclear, vague: after all who are we to understand eveything of the silly complexity that surrounds us? It’s easier to be carried away, stunned by the flow of ideas and by the whirlwind of gags that follow each other relentlessly, while we laugh almost at every page and make our way through references to artists, groups and art movements of the last hundred and a half years, in a system of special guests and flashbacks that intertwines with narration without ever being an end in itself. Art Comic comes out for the same publisher and in the same year of Sabrina but represents its complete opposite. While in Drnaso the characters seem deliberately emotionless, nearly without facial expressions, in Thurber they look caricatural, exaggerated, hilarious and beatifully designed one by one. While Drnaso regulates everything through an obsessive logic, Thurber gives rise to an unbridled explosion of creativity: he is deeply interested in building a narrative but he likes to develop a loose structure, so that his book looks totally different from the usual “graphic novel” people are used to see in bookstores today.

Thurber’s endings are often sudden, almost cut off, and never definitive, as in the tradition of post-modern literature. In the comic book edition of Art Comic, Cupcake figured out – after an encounter with Mr. Colostomy, the talking horse recurring in every Thurber’s comic – how to turn a toilet bowl into gold, finding members of Gelatin art group inside it. When they invite Cupcake to join them, he dives into the toilet, as in Trainspotting via the Atalante by Jean Vigo. Put at the end of Art Comic #5, this was an unexpected ending, even for Thurber, since a lot of narrative threads remained totally unsolved. I spent months wondering (while I was also thinking about something else, of course) if it was really over and so it was a pleasant surprise to discover a never-seen-before sixth chapter of 33 pages, which leads to the conclusion (or almost) of the story. In the book you’ll find even some new “special contents”, i.e. 6 pages in which the characters and Thurber himself reflect on the story we’ve just finished to read. Instead we can’t find in the book the beautiful essay/editorial written by Thurber for the fourth issue of the series on the theme of the mystifying historicization of art. But these are minor details for those who haven’t still read Art Comic and, if you are among them, you’ve to do it as soon as possible. As expected, it is absolutely my best of 2018, without competitors.