Un’intervista a Conor Stechschulte

In occasione della prossima imminente edizione di BilBOlbul, dal 24 al 26 novembre a Bologna, Conor Stechschulte sarà protagonista di una mostra intitolata Il peso dell’acqua, che inaugurerà presso la galleria Spazio & il 24/11 alla presenza dell’autore, per poi prolungarsi fino al 20 dicembre. Negli stessi giorni troverà pubblicazione in Italia per 001 Edizioni I dilettanti, traduzione di The Amateurs, graphic novel edito nel 2014 da Fantagraphics dopo una prima versione autoprodotta. E a breve è prevista inoltre l’uscita del terzo capitolo di Generous Bosom, la serie che il cartoonist americano sta realizzando per gli inglesi di Breakdown Press.

Per presentare Conor al pubblico italiano gli abbiamo rivolto qualche domanda sulla sua formazione, le sue opere e il suo processo creativo. L’intervista è stata realizzata via e-mail tra settembre e ottobre 2017 da Alessio Trabacchini e Gabriele Di Fazio, cui si è aggiunta in seguito Elisabetta Mongardi. La traduzione in italiano è di Mauro Meneghelli. Buona lettura.

The Amateurs mostra la tua capacità di far scorrere il mistero nel quotidiano, sembra che attraverso i vari personaggi (nella storia principale e nella cornice) la storia illustri diverse modalità di rapportarsi all’elemento misterioso e non razionale dell’esistenza. Non sappiamo se sei d’accordo con questa lettura ma vorremmo cominciare proprio dal tuo rapporto con questo elemento e da come pensi che possa essere trasmesso, mostrato o evocato attraverso l’arte.

Le storie di fantasia possono aiutare a guardare da altri punti di vista ciò che viviamo. Questo è un grande dono che ho ricevuto dell’arte, e che cerco di trasmettere. Inoltre mi piace molto quando sogno qualcosa di veramente banale – come aver spostato un oggetto nel mio appartamento o aver ritrovato qualcosa in macchina – e poiché si adatta perfettamente alla realtà è come una strana ma noiosa bomba a orologeria che esplode all’improvviso. Rende il resto della mia giornata un po’ irreale. Mi è successo anche di recente, ho sognato di aver inviato alcune foto sul mio cellulare a un estraneo, che ha risposto semplicemente “Ah!”. Qualche giorno dopo il sogno, ho avuto un momento di assoluto panico al pensiero che questa cosa leggermente imbarazzante fosse successa davvero.

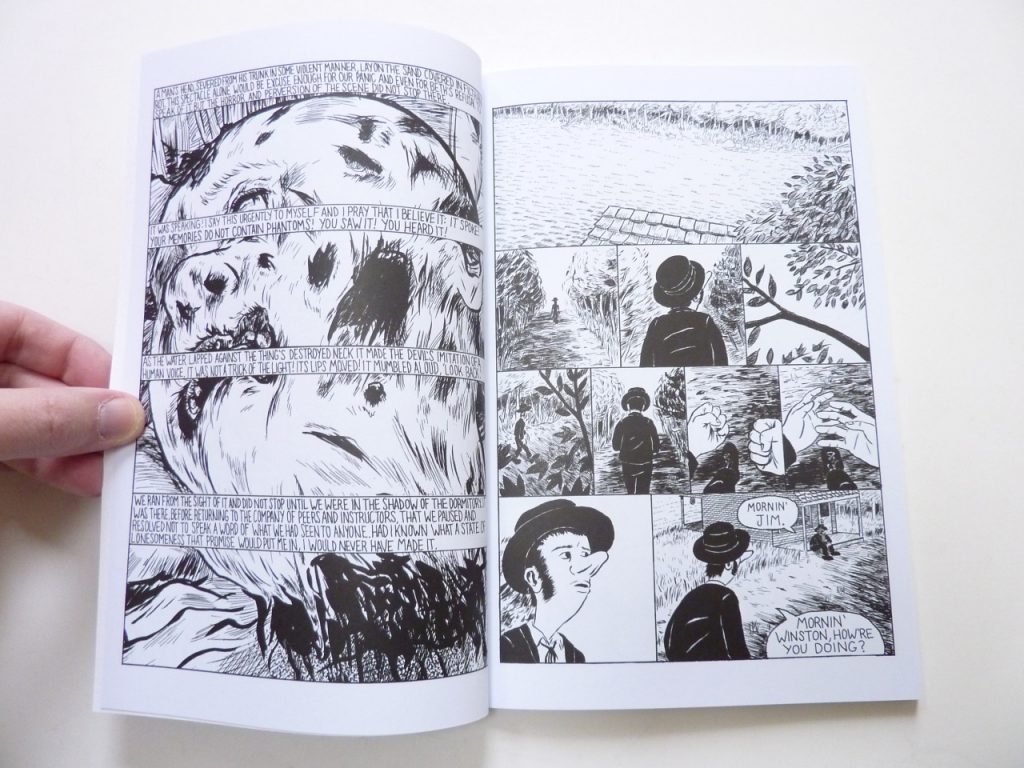

Quindi, se sognare oggetti comuni è importante per la tua arte, è anche vero che l’incipit di The Amateurs mostra il processo contrario, dato che qualcosa di insolito si materializza nella vita di tutti i giorni. La testa ritrovata nel fiume innesca infatti una serie di eventi straordinari, come succede con l’orecchio tagliato trovato nel campo all’inizio di Velluto blu di Lynch. Se i tuoi fumetti svelano la permeabilità tra il mondo reale e quello onirico, puoi raccontarci meglio come l’esperienza del sogno influenza il tuo lavoro? Inoltre, ci sono autori che ami particolarmente tra coloro che hanno percorso questa strada?

Mi piacerebbe parecchio fare dei sogni lucidi, ma finora non ci sono riuscito se non in quei momenti, la mattina presto, in cui posticipo continuamente la sveglia. Ho trovato molte soluzioni a problemi di sceneggiatura o di disegno in questo “spazio” (mi ricordo per esempio l’immagine finale di The Dormitory con il ragazzo che fuma alla finestra del seminterrato).

Un autore che mi viene subito in mente a questo proposito è Jesse Ball. Ho avuto il privilegio di averlo come tutor durante il mio semestre alla School of the Art Institute di Chicago la scorsa primavera e ho appena letto Sleep, Death’s Brother, il suo libro sul sogno lucido. Le sue idee sui sogni sono molto più interessanti delle mie e mi piace particolarmente la sua concezione dello spazio onirico come un territorio dove allenare la volontà; il suo libro è infatti destinato ai bambini e ai detenuti per l’esercizio della forza di volontà in circostanze particolari.

La gran parte dei miei autori e artisti preferiti ha “percorso questa strada”. Uno dei più importanti per me è Kobo Abe, e per Generous Bosom mi sto ispirando molto al suo libro Secret Rendezvous. Nei suoi quaderni Werner Herzog non fa distinzione tra avvenimenti quotidiani e immaginario onirico (sebbene affermi di non sognare la notte). L’idea seminale per The Amateurs è scaturita da una scena che ho letto nei suoi diari in cui descrive dei macellai incapaci sulle sponde di un fiume a Iquitos. Nell’ambito del fumetto penso che Olivier Schrauwen sia un maestro delle situazioni sognanti/fantasiose/soggettive e nel giocare con il loro scarto umoristico rispetto alla realtà circostante. Altri libri/autori/artisti per me importanti in questo filone sono L’allegra compagnia del sogno di J.G. Ballard, Solaris di Stanislaw Lem, Il pellegrinaggio in Oriente di Hermann Hesse, L’uccello che girava le viti del mondo di Haruki Murakami, chiaramente Borges, Philip K. Dick, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Tarkovsky, sicuramente Lynch… E molti altri che sto dimenticando.

L’edizione Fantagraphics di The Amateurs presenta alcune differenze dalla prima versione che ti sei autoprodotto nel 2011. La più significativa è la sostituzione dell’introduzione scritta a mano con una storia completamente nuova di due studentesse che trovano la testa di un uomo nel fiume, lo stesso fiume dove faranno un rito per celebrare la promozione insieme alle compagne di scuola. Perché hai deciso di modificare l’originale e come hai creato questa nuova storyline?

Ero semplicemente insoddisfatto della lettera da un punto di vista estetico. Era una delle ultime cose che avevo aggiunto al fumetto e più la guardavo meno mi convinceva. Un paio di mesi dopo aver pubblicato l’albo ho avuto l’idea di questa seconda storyline e ho pensato: “Se mai avrò modo di ristamparlo l’aggiungerò”. Così quando Fantagraphics me ne ha dato l’opportunità è stata una delle prime cose che ho fatto.

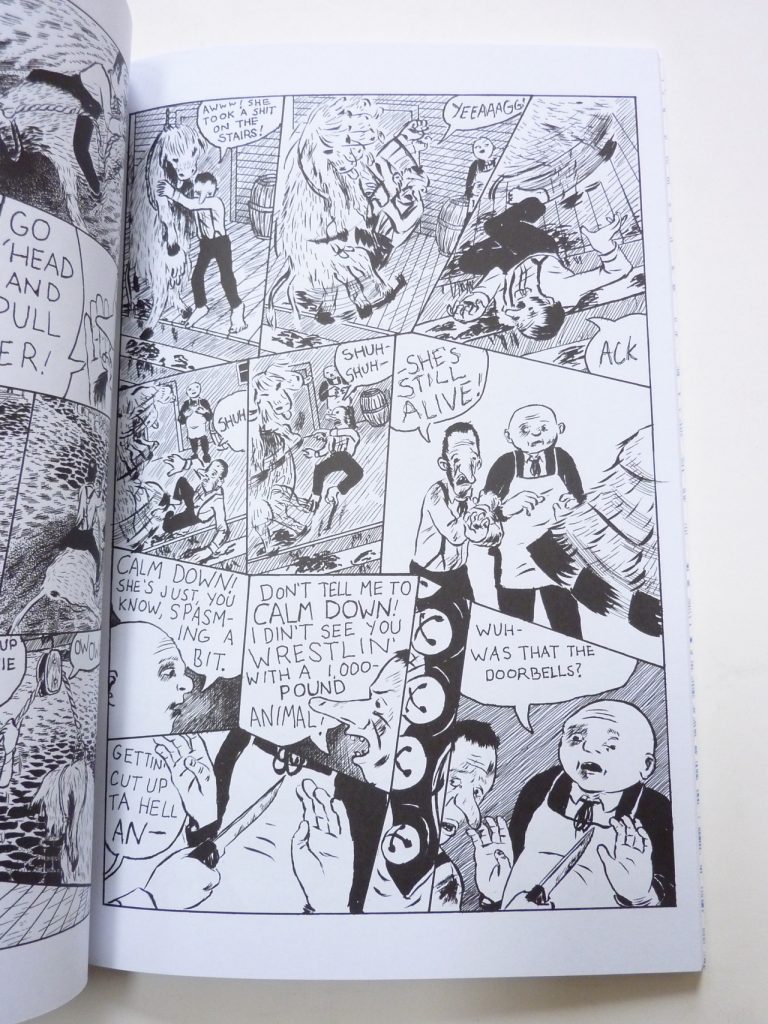

Gli animali hanno un ruolo chiave in The Amateurs, sembrano forti e consapevoli, mentre Jim e Winston, i due macellai protagonisti della storia, sono deboli e confusi. Inoltre la violenza brutale di alcune sequenze in cui gli animali sono considerati semplicemente come cibo sembra condannare la scelta di mangiare carne animale. Volevi comunicare una sorta di “messaggio” con questa storia? O l’interpretazione è più metaforica?

Ho deciso che Jim e Winston dovessero essere dei macellai perché volevo facessero un lavoro intimamente correlato con la morte. Volevo raccontare come le persone, invece di fare i conti con la morte, la considerano una cosa che non li riguarda e finiscono per collocarla nel corpo altrui. E questo porta sempre a un danno per se stessi e per gli altri.

Detto questo, quando ho realizzato il libro ero vegetariano da dodici anni. Ma poi ho ricominciato a mangiare carne. Ahah, non so se questo spiega qualcosa della storia… Se qualcuno decidesse di diventare vegetariano dopo aver letto il libro sarebbe fantastico.

Leggendo The Amateurs, l’impressione è che il genere dei tuoi personaggi non sia casuale. Oltre ad alcuni indizi evidenti (la scuola femminile, le due clienti), tutti gli animali che ad un certo punto si ribellano contro gli umani sono femmine (la scrofa, la giumenta, la mucca) mentre i maschi sono più sottomessi (il maiale va nel mattatoio di sua iniziativa, la tartaruga viene torturata nel bosco). Sembra anche che il potere minaccioso del fiume, quale che sia, non colpisca le donne: lo usano per fare il bagno, lavare i panni, fare dei riti senza che gli succeda nulla. Quando, invece, Winston e Jim entrano nell’acqua vengono letteralmente fatti a pezzi. C’è anche una scena in cui Winston, subito dopo essersi macinato le dita, urla alle due clienti che non tollererebbe mai che una donna criticasse il suo lavoro. Per non parlare del fatto che gli torna in mente che quando erano bambini le due clienti lo avevano vestito da femmina. Ci sembra dunque che il tuo libro sia pieno di sottili riferimenti alle relazioni tra uomini e donne (o alla concezione generale di mascolinità e femminilità). Tutto ciò è intenzionale o lo stiamo sovrainterpretando? E il fiume c’entra qualcosa con la rappresentazione della femminilità nel libro?

Grazie per questa lettura così accurata. È assolutamente vero che, almeno nelle mie intenzioni, il genere era un aspetto fondamentale che volevo affrontare.

Anche a rischio di spiegare troppo o escludere interpretazioni migliori e più interessanti, direi che The Amateurs è un tentativo di prendere in giro, ridicolizzare e fare a pezzi (letteralmente, ahah) la concezione di una mascolinità autosufficiente, non-relazionale, quella dell’uomo che ha tutte le risposte. È questo ciò che Jim e Winston tentano di rappresentare per i personaggi femminili del fumetto.

Di grande ispirazione per The Amateurs è stato il libro di Kaja Silverman Flesh of my Flesh, che propone di sostituire il mito di Edipo con quello di Orfeo per quanto riguarda il genere – una storia basata sulla mortalità invece che sulla castrazione. Afferma che la nostra mortalità ci permette di relazionarci gli uni con gli altri per analogia, attraverso le nostre somiglianze, piuttosto che metaforicamente, cosa che presuppone sempre una gerarchia. Ho utilizzato molte di queste idee e ho preso in prestito l’immaginario del mito di Orfeo (ad esempio la testa trascinata sulla riva).

Grazie per aver evidenziato l’aspetto del genere a proposito degli animali ma non penso di averlo fatto intenzionalmente. Credo che un modello simile emerga anche in Generous Bosom, dove il protagonista e “eroe” della storia è in realtà molto passivo.

Quanto all’acqua, credo sia rappresentativa di uno stato estatico/trascendente/indefinito e non riferita al concetto di genere.

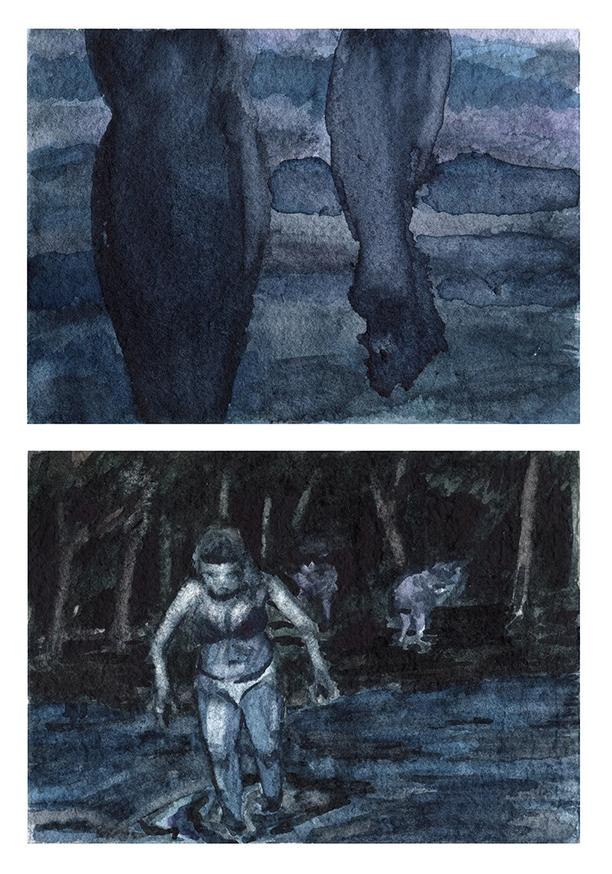

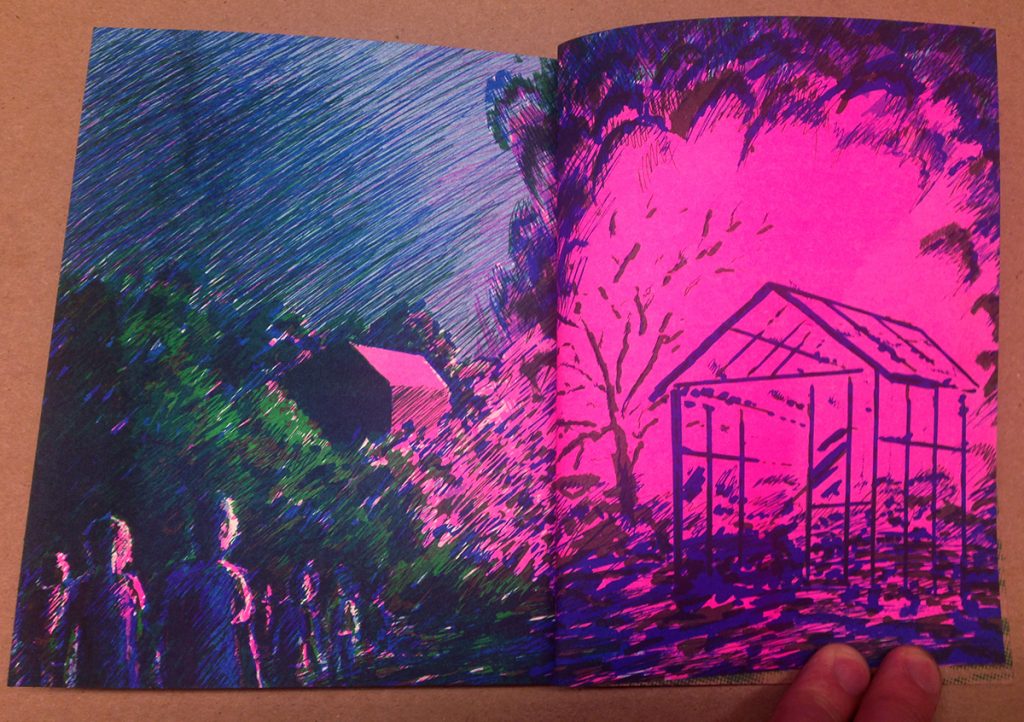

L’acqua è un elemento ricorrente nei tuoi fumetti, e talvolta ha un ruolo fondamentale. Può essere il fiume rituale in The Amateurs, la pioggia da cui prende forma Generous Bosom, il lago delle tensioni acute ma impalpabili di Glancing, il mare che accoglie i giochi di Water Phase e il flusso narrativo di Christmas in Prison. Se la consideriamo come un simbolo, l’acqua è necessariamente sfaccettata, fluida, e sembra collegata al desiderio, al cambiamento, all’epifania. È dove succedono le cose, dove si raccontano le storie e si svelano i segreti. Perché l’acqua è così importante per te?

Grazie per aver rintracciato in maniera così completa questa immagine nei miei lavori! Avete delineato così bene il modo in cui ho utilizzato l’acqua che non so se posso aggiungere altro…

Dei significati simbolici che avete elencato mi identifico maggiormente con l’idea di cambiamento. L’acqua è dove i confini si infrangono, le cose si dissolvono, le definizioni si spostano.

Per quanto si debba essere chiari ed esplicativi nel raccontare una storia, soprattutto con i fumetti (ecco un tizio, ed eccolo di nuovo, vedi? Porta le stesse scarpe e lo stesso cappello, a parte il fatto che gli è caduto l’ombrello, ed eccolo, è di nuovo lui che si sta chinando per raccoglierlo), l’acqua concede uno spazio necessario alla vaghezza.

È un luogo che permette di sospendere l’interruzione tra le varie vignette (o forse è un modo di rappresentare quel non-spazio tra loro). Puoi raffigurare un personaggio con tratti puliti e decisi per la maggior parte della tua storia ma, se pensi allo stesso personaggio in una vasca piena d’acqua, le linee diventano tutte ondulate. E possono essere diverse, dunque.

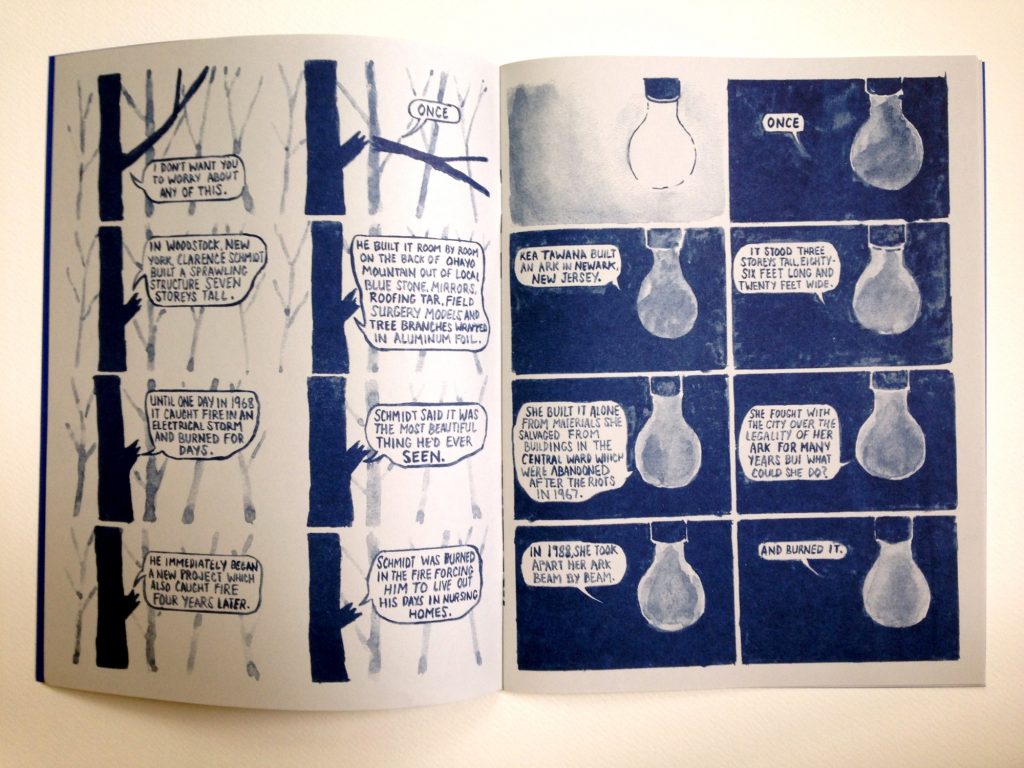

Questo conferma la tua tendenza a cercare modalità sempre nuove per raccontare una storia. Per esempio anche il tuo ultimo lavoro, Tintering, è innovativo, perché invece di disegnare i personaggi racconti la storia di cinque artisti autodidatti attraverso diversi oggetti rotti e usando vignette molto simili tra loro, mentre il contenuto è veicolato soprattutto attraverso il testo. Come sei arrivato a questo e perché è importante per te puntare l’attenzione sugli oggetti?

L’ispirazione per il soggetto del fumetto è stata una lezione di storia dell’arte di Lisa Stone, che è un’insegnante incredibile, generosa e acuta sul tema degli artisti autodidatti e vernacolari. Il modo in cui questi artisti si rapportavano agli oggetti era diverso da come noi abitualmente facciamo (o dobbiamo fare) nella quotidianità. Kea Tawana, per esempio, smontava con meticolosità e attenzione quei vecchi edifici di Newark. Aveva un’enorme sensibilità per l’artigianato e non poteva sopportare che dei materiali utili andassero sprecati. Buona parte del lavoro di questi artisti autodidatti è una risposta alla produzione massiva di oggetti tipica della nostra cultura, e all’incuria e spreco successivi.

Inizialmente pensavo che il fumetto dovesse essere come quelle sezioni di Christmas in Prison in cui il personaggio fa una sorta di monologo rivolto al lettore. Allora ho disegnato un tipo dietro un albero e poi ho pensato che avrebbe allungato una mano e spezzato un ramo. A quel punto mi è sembrato più corretto che fosse il ramo a parlare. La maggior parte delle storie di questi artisti iniziano e finiscono tragicamente – subiscono una perdita, creano qualcosa di bello che viene distrutto. Mi è sembrato giusto che fosse qualcosa di rotto a raccontare queste storie e che parlasse dalla parte della ferita.

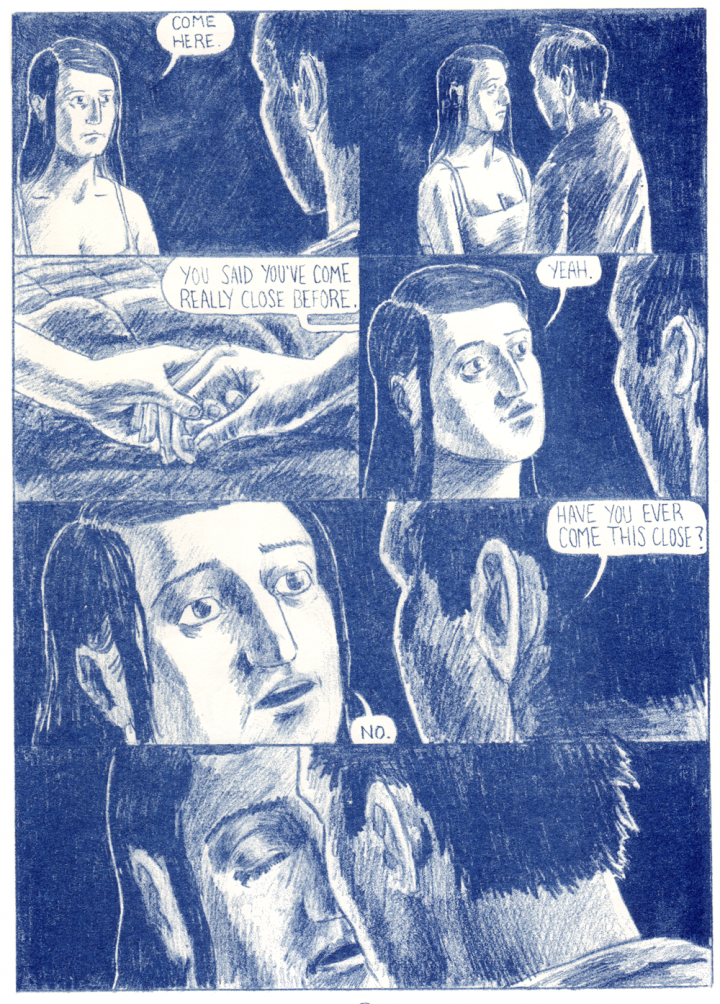

In Generous Bosom esplori in maniera approfondita un tema per te ricorrente. Potremmo chiamarlo “voyeurismo” ma sarebbe semplicistico, è piuttosto la questione continua di “chi guarda” e delle dinamiche del guardare. Questo tema è presente in molte delle tue opere ed è fondamentale nel tuo albo autoprodotto The Dormitory. Ma chi è il vero voyeur, l’autore o il lettore? O qualcun altro?

Difficile rispondere brevemente a questa domanda, soprattutto perché la considero una questione aperta, su cui sto ancora lavorando… Non credo che qualcuno possa semplicemente guardare qualcosa senza, consapevolmente o meno, partecipare o alterare ciò che sta guardando. Non penso di poter dire chi sia il “vero” voyeur.

Forse i fumetti si basano proprio sul fatto che l’atto di osservare influenza ciò che si guarda. Ci puoi parlare della tua esperienza di lettore? Come ti piace leggere/guardare i fumetti?

Sì, credo che questa sia una giusta considerazione. In un fumetto non si sfugge al fatto che qualsiasi cosa si trovi sulla pagina è stata messa lì da qualcuno e nel disegnare non c’è differenza tra ciò che si vede e come lo si vede.

Detto questo, come lettore mi piace molto considerare il fumetto come un medium in cui mettere del tuo. Non è la stessa cosa di guardare un film, qui è il pubblico/lettore ad animare l’azione. Per rispondere alla domanda, penso che Generous Bosom indaghi la dinamica della lettura dei fumetti – puoi pensare di osservare qualcosa che succede sia come lettore che come autore ma in realtà sei tu a far succedere quella cosa.

Mi piace leggere più volte i fumetti. E mi piace il fumetto perché è un mezzo che incoraggia questo processo; è sempre facile ritrovare una scena preferita, è a portata di mano. E inoltre leggendo i fumetti si può passare velocemente dall’oggetto della storia al mezzo con cui è raccontata. La densità e la profondità di un fumetto davvero bello sono immediatamente accessibili.

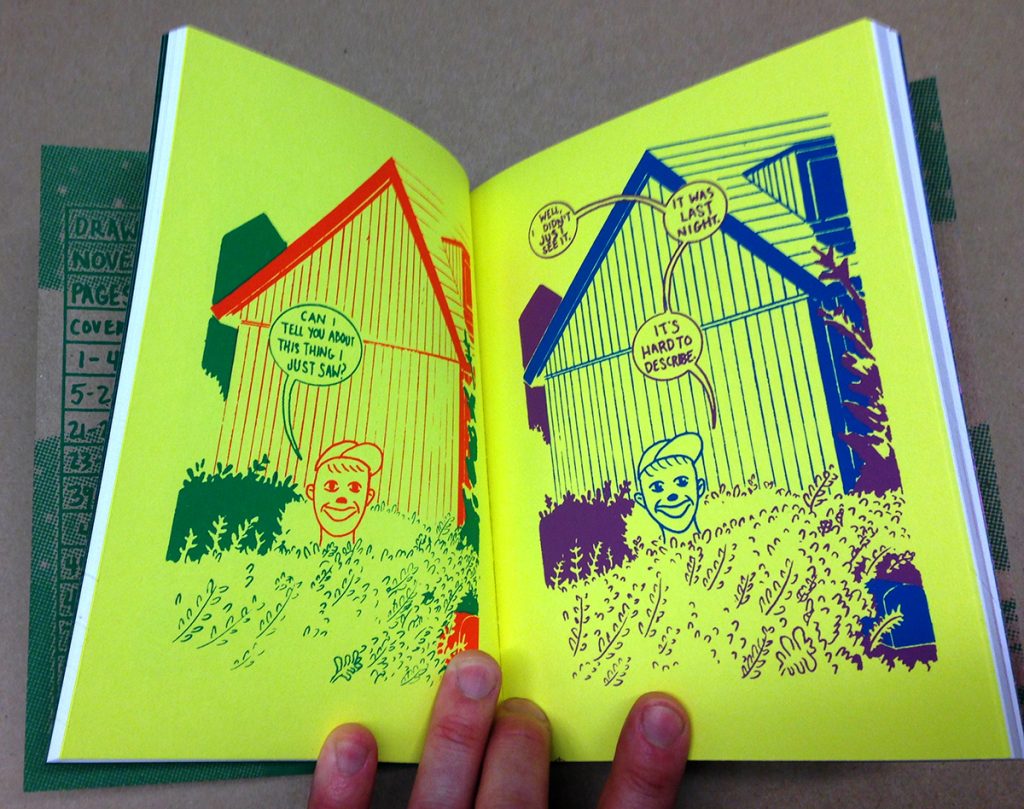

I tuoi fumetti bilanciano flusso e struttura in una maniera unica e originale e in genere è molto difficile capire se sei partito dalla trama o dai disegni. Glancing, un’opera basata sull’accostamento di acquerelli senza testo, potrebbe essere un ottimo esempio. Qual è la tua concezione di fumetto e narrazione?

Grazie! Sulla mia concezione di fumetto e narrazione penso si possa tornare a ciò che ci siamo detti sull’acqua e sulla comparsa del misterioso e dell’irrazionale nel quotidiano. Struttura=Vita quotidiana=Narrazione principale di un fumetto/Disegni lineari/Chiarezza, mentre Flusso=Mistero=Acqua/Cambiamento/Irrazionalità.

Nei miei fumetti tento di mettere tutti i pezzi in fila, di raccontare una storia, e per farlo bisogna stabilire delle regole che il lettore possa seguire e su cui possa fare affidamento (credo che questo sia ciò che intendete con “struttura”). Queste regole si accumulano e possono presto diventare ostacoli alla libertà e alle potenzialità proprie del mondo che ho creato, che sono la fonte di energia per il seguito della storia. Per me a questo punto è il momento di cambiare le regole, o di lavorare a un altro progetto con regole diverse o ancora imprecise.

Lavorare a Glancing è stato in questo senso molto divertente e dinamico, perché facevo tre o quattro disegni e poi potevo inserirne altri nel mezzo, o dopo, o prima. Potevo osservare tutto il lavoro disposto sul pavimento e farmene un’idea complessiva. Voglio lavorare ad altri fumetti in questo modo.

Un altro aspetto interessante del tuo lavoro è che in genere eviti l’opposizione tra fumetti narrativi e non-narrativi – e tra “fiction” e “poetry comics” – alternando le due modalità o dimostrando la loro sostanziale identità nel campo del fumetto. Concordi con questo punto di vista?

Grazie di nuovo! Sì, ritengo che anche questo aspetto sia collegato alla domanda di prima. Aggiungerei che le decisioni sulla struttura, se qualcosa debba essere “poetico” o “narrativo” e così via, sono prese seguendo l’entusiasmo per ciò su cui sto lavorando. Spesso inserisco qualcosa di misterioso/poetico/irrazionale/non-narrativo perché mi sto per annoiare di una fase della storia o perché voglio evitare una scena che non mi sembra interessante da realizzare o da leggere.

Il tuo lavoro guarda sia ai fumetti letterari degli anni ‘90 sia alla sperimentazione formale che si distingue dagli standard del graphic novel, come Fort Thunder e gli art comics in genere. Ma qual è il tuo background? Anche al di fuori dei fumetti, ovviamente.

La mia più grande influenza sono gli amici che ho trovato al Maryland Institute College of Art, le persone che facevano parte del gruppo Closed Caption Comics. Da giovani abbiamo imparato tutti insieme a fare fumetti. Era il periodo in cui stava nascendo PictureBox e molte delle cose di Fort Thunder stavano emergendo ed era perfetto – sembrava che l’immediatezza di quei lavori e la loro forza visuale si rivolgessero proprio a noi. Kramers Ergot 4 e 5, il vecchio sito di Fort Thunder e conoscere CF e Brian Chippendale alla Small Press Expo ci fece capire che quello era il mondo dell’arte in cui potevamo trovare il nostro spazio. Direi che per un bel po’ quella è stata la dimensione che mi interessava: la mia cerchia di amici e quel paio di spiriti guida là fuori.

Oltre a questo, crescere nella Pennsylvania rurale ha avuto una grande influenza sui mondi immaginari dei miei libri. Ho letto anche molta letteratura. Ho appena terminato un master alla School of the Art Institute di Chicago. Non so se però siete più interessati alla mia formazione e alle mie influenze o alla mia biografia…

Soprattutto alle tue influenze, ma anche all’aspetto biografico nella misura in cui ha influenzato il tuo lavoro…

Oltre a Closed Caption Comics, ho partecipato ad altri progetti artistici che hanno avuto un grande impatto sulla mia vita. Appena finita la scuola, ho dato una mano alla creazione della galleria Open Space a Baltimora. Abbiamo curato degli spettacoli, ospitato performance, creato una biblioteca di fanzine e abbiamo messo in piedi la Publications and Multiples Fair. Sto anche aiutando a organizzare la prima Chicago Art Book Fair.

Per sette anni sono stato anche in una band chiamata Witch Hat che ho fondato con Noel Freibert e Lane Milburn. Dopo tre anni Lane ha lasciato la band e si è unito a noi Chris Day. Chris e io ora siamo in una nuova band che si chiama Lilac, con Anya Davidson e Kenny Rasmussen, qui a Chicago (io e Chris ci siamo trasferiti nello stesso periodo). Quando sono entrato nella scena underground dei fumetti c’erano molti punti di contatto con la scena musicale underground. Ho incontrato molti musicisti grazie ai fumetti e molti fumettisti grazie alla musica.

Pensi che la tua arte o il tuo approccio all’arte siano cambiati da quando non sei più a Baltimora? A Chicago c’è una scena fumettistica importante e una lunga tradizione di arte contemporanea che sicuramente ti avranno stimolato, ci viene da pensare agli Hairy Who ma ci sono probabilmente molte cose che in Europa sono poco conosciute.

La mia arte e il mio approccio sono sicuramente cambiati molto da quando ho lasciato Baltimora. Ho frequentato una nuova scuola negli ultimi due anni e l’essere in contatto con tantissime nuove opere, persone e idee è stato incredibilmente rinvigorente e travolgente. Penso che per digerire tutto ciò mi ci vorranno degli anni.

Quanto allo stile di vita, trasferirmi qui e frequentare la scuola mi ha permesso di evitare i lavori non artistici (almeno per ora). È una grande opportunità che prima non pensavo di potermi permettere. Ora sono più concentrato sull’idea di fare arte a tempo pieno, o almeno di farla e insegnarla.

Chicago è una città fantastica per i fumettisti. C’è una comunità splendida, di grande supporto, e realtà come la serie di reading Zine Not Dead gestita da Matt Davis e Brad Rohloff, che porta avanti la tradizione delle letture performative di fumetti avviata da Lyra Hill con Brain Frame. E poi a soli cinque isolati da casa mia vivono tutti insieme Anya Davidson, Lane Milburn, Margot Ferrick e Andy Burkholder (anche Edie Fake viveva lì, nella mansarda). A due isolati di distanza ma in un’altra direzione vivono i miei cari amici Molly O’Connell e Chris Day – i quali fanno entrambi cose molto belle, nell’ambito dei fumetti e non solo.

Abbiamo già parlato di Conor Stechschulte qui:

Qualche fumetto dalla Small Press Expo (Mountain Comic & Generous Impression)

Best Comics of 2014: The List (The Amateurs, Generous Bosom, Glancing)

An interview with Conor Stechschulte

Conor Stechschulte is the author of The Amateurs, a graphic novel published by Fantagraphics in 2014, of Generous Bosom, a series for Breakdown Press now at its third installment, and of several self-published comics. Conor will be in Italy for BilBOlbul festival in Bologna, where he will have Il peso dell’acqua (The Weight of Water), an exhibition of his works open from 24th November until 20th December at the Spazio & gallery. And in the same days 001 Edizioni will publish I Dilettanti, the Italian translation of The Amateurs.

We asked some questions to Conor to introduce him to the Italian audience. The interview was conducted by e-mail between September and October 2017 by Gabriele Di Fazio, Elisabetta Mongardi and Alessio Trabacchini.

The Amateurs reflects your ability to introduce mystery in everyday life. The story seems to illustrate through the various characters (both in the main plot and in the frame) different ways to relate to the mysterious and non-rational aspect of existence. We don’t know if you agree with this interpretation, but we would like to begin this interview talking about your relationship with this element and how you think it can be communicated, displayed or evoked through art.

Fiction can help demonstrate ways to look sideways at what we’re experiencing. This is a great gift I’ve gotten from art and one I’m trying to pass on. Similarly, I really enjoy when I dream about something really banal – that I’ve moved a small object in my apartment or retrieved something from the car – and because it fits right in with reality, it’s like a weird boring time bomb that goes off with a light pop. It makes the rest of my day feel a little unreal. This just happened to me recently, I dreamt that I’d accidentally sent a bunch of pictures from my phone to a stranger and he’d replied simply, “Ha”. Several days after the dream I had a real moment of panic that this lightly embarrassing thing had actually occurred.

So, if dreams of objects from ordinary life are important for your art, it’s also true that the beginning of The Amateurs shows the opposite process, since something strange pops in everyday life. In fact the head found in the river kicks off a series of extraordinary events, as it happens with the severed ear found in the field at the beginning of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet. Your comics reveal the permeability between dreams and reality, but can you tell us more about how dreaming experience goes into your work? And do you look at some artists in particular who have taken this road?

I’d really like to lucid dream, though so far I’ve not had any success with it except in the early-morning time between hitting “snooze” on the alarm. I’ve come up with a lot of solutions to story problems and images in this space (one I can recall for sure is the final image from The Dormitory of the guy smoking in the basement window).

An author that immediately springs to mind on this subject is Jesse Ball. I had the privilege of advising with Jesse during my last semester at the School of the Art Institute this past spring and I just read Sleep, Death’s Brother, his book on lucid dreaming. He has much more interesting and useful things to say about dreaming than I do but I am especially excited by his idea of the dream-space as a training ground for the will; his book on dreaming is in fact intended for children and incarcerated persons for the exercise of the will under restricted circumstances.

Most of my favorite authors and artists have “taken this road.” Kobo Abe is an important favorite of mine, I’m thinking a lot about his book Secret Rendezvous in the most recent volumes of Generous Bosom. In his journals, Werner Herzog makes no distinction between everyday events and dream imagery (though he claims not to dream at night). The originating idea for The Amateurs sprung from a scene I read in his journals where he describes inept butchers on the banks of a river in Iquitos. In comics, I think that Olivier Schrauwen is a master of dreamlike/fantasy/subjective points of view and playing with the humor of their discontinuity with outside reality. Other important books/authors/artists for me in this vein are J.G. Ballard’s Unlimited Dream Company, Solaris by Stanislaw Lem, The Journey to the East by Hermann Hesse, Wind up Bird Chronicles by Haruki Murakami, Borges of course, Philip K. Dick, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Tarkovsky, Lynch of course… And lots of others I’m forgetting.

The Fantagraphics edition of The Amateurs shows some differences from the first version you self-published in 2011. The most significant is the replacement of the hand-written introduction with a completely new storyline about two schoolgirls finding a man’s head in the river, the same river where they will perform a graduation ritual along with their classmates. Why did you decide to revise the original comic and how did you create this other storyline?

It started with simple dissatisfaction with the letter visually. It was one of the last things I had added to the comic and the more I looked at it the more unconvinced I was. A couple months after I’d self-published the book, I had the idea for that second storyline and thought, “Well if I ever have the chance to reprint it, I’ll include that”. So when the opportunity came along with Fantagraphics, it was one of the first things I did.

Animals have a key role in The Amateurs, they look strong and aware, while Jim and Winston, the two butchers who are the main characters of the story, are weak and confused. This, and the use of brutal violence in some sequences where animals are considered only as food, seem to imply a condemnation of eating animal meat. It should be interesting to understand if you wanted to convey a sort of “message” or if the interpretation is more metaphorical.

I made Jim and Winston butchers because it’s a profession that deals intimately with death. I wanted to talk about how people, rather than reckoning with death, will externalize it and locate it in the body of another, this always leading to harm on both sides of the equation.

That said, at the time I made the book I’d been a vegetarian for twelve years. I’ve since starting eating meat again. Haha, not sure if that shines any kind of light on the content… If someone were to decide become vegetarian after reading the book, that’d be great.

While reading The Amateurs, the impression is that the gender of your characters is not randomly chosen. In addition to some obvious hints (the all-girls school, the two customers…), all the animals that at some point rebel against humans are female (the sow, the mare, the cow), while the male are somehow more subdued (the pig walks into the slaughter of its own accord; the turtle gets tortured in the woods). It also seems like whatever the sinister power of the river is, it doesn’t affect women: they bathe, wash their clothes and make rituals in it, and nothing seems to happen to them. On the other hand, when Winston and Jim go into the water, they get literally shredded. There is also a scene where Winston – right after he has grinded his own fingers – yells at the two customer, saying he won’t put up with a woman telling him his work is not good enough. Not to speak of the fact that he remembers the two customers dressing him up as a girl when they were all kids. It seems to me that your book is filled with subtle references to men-women relationships (or to the general opposition between masculinity and femininity). Was that intentional or we are overthinking it? And does the river have anything to do with the representation of femininity in your book?

Thank you for such a close reading. You’re absolutely right that, at least in terms of my intentions, gender was a primary thing I was trying to address.

At the risk of over-explaining and squeezing out better and more interesting interpretations, I’d say that The Amateurs is an attempt to lampoon, ridicule and take apart (literally, haha) the idea of self-reliant, non-relational masculinity – the man who has all the answers. This is the character that Jim and Winston try to perform for the women in the book.

A huge influence on The Amateurs was the book Flesh of my Flesh by Kaja Silverman. She argues for replacing the Oedipus myth with the Orpheus myth with regards to gender – a story based on mortality rather than castration. She says our mortality allows us to relate to one another analogously, through our resemblances rather than metaphorically which always presumes a hierarchy. I was trying for a lot of these ideas and borrowed imagery from the Orpheus myth (i.e. the head washed up on the shore).

Thank you for pointing out this pattern in the gender of the animals, I don’t think I consciously set that up. I think a similar sort of pattern is emerging in Generous Bosom as well, where the main character and “Hero” of the story is actually very passive.

As for the water, I think of the water as being representative of an ecstatic/transcendent/undefined state rather than being specifically gendered.

Water, of course… It is a recurring element in your comics, and sometimes plays a major role. It may be the ritual river in The Amateurs, the rain from which the facts of Generous Bosom develop, the lake of impalpable but sharp tensions in Glancing, the sea where the games of Water Phase unfold, and Christmas in Prison’s narrative stream. If we consider water as a symbol, it is necessarily multifaceted, fluid, and seems to be related to desire, change, epiphany. It is the place where things happen, stories are told, secrets come to light. Why is water so important to you?

Thank you for tracking this image so comprehensively throughout my work! You’ve done such a good job of outlining how I’ve used water that I’m not sure if I can add anything…

Of the symbolic meanings you’ve listed I identify most with the idea of change. Water is a place where boundaries break down, things dissolve, definitions shift.

With how clear and declarative one must be in telling a story, especially with comics (here’s a guy, now here he is again, see? He’s wearing the same shoes and hat, except now he’s dropped his umbrella, and here he is again but now he’s bending to pick it up), water provides a needed space for vagueness. It’s a place where the closure occurring between each panel might be suspended (or maybe it’s a way of depicting that no-space in between). You can draw a clean, clear black-outlined character for most of your book but if you reflect the same character in a bowl of water, their lines go all wavy. They can be different.

This confirms your are constantly looking for new ways of telling a story. For example another rule-breaking work is your most recent one, Tintering, where you didn’t draw characters but you told the story of five self-taught artists using different broken objects, with the single panels very similar to each other, while the content is mostly developed with text balloons. How did you come up with this, and why are you focusing your attention on objects?

The subject matter for the comic all came from an art history class I took which was taught by Lisa Stone, who is an incredible, generous, brilliant scholar on the subject of self-taught and vernacular artists. The way a lot of these artists related to objects was different from how we do (or must) in everyday life. Kea Tawana, for example, meticulously and respectfully took apart these old buildings in Newark. She had immense sensitivity to craftsmanship and couldn’t stand to see good materials go to waste. Much of the work of self-taught artists serves as a response to our culture’s massive generation, disregard and waste of objects.

I was originally thinking the comic might look like some of the stuff that I’d made for Christmas in Prison, with a character sort of delivering a monologue to the reader. I drew a guy standing behind a tree and then I thought maybe he’d reach out and break a branch off. Then it seemed more correct for the broken branch to talk. Most of the stories of these artists begin and end tragically – they undergo a loss, they make something beautiful which is itself destroyed. It seemed right that something broken would tell those stories and that they’d speak from the site of their injury.

In Generous Bosom, one of your recurring themes is explored thoroughly. We could call it “voyeurism” but it would be simplistic, it is a permanent question about “who watches” and the dynamics of watching. This theme can be found in a lot of your books and is essential in the self-published short story The Dormitory. But who is the real voyeur in your comics, the author or the reader? Or who else?

This is a tough question to answer succinctly. Mostly because it’s still an open one for me since I’m still trying to work these things out…

I don’t think anyone gets to just watch anything without, knowingly or not, participating or altering whatever it is they’re watching. I’m not sure if I can say who is the “real” voyeur.

Maybe comics are based on the fact that the act of watching affects the things you watch at. Can you tell us about your experience as a reader? How do you like to read/watch comics?

I think you’re right. In a comic, there’s no escaping the fact that whatever is on the page was put there by someone and through the act of drawing there’s no difference between what is seen and how it is seen.

That said, on the reading side of it I really like that comics are an elective medium. It doesn’t happen to the audience the way movies do, the audience/reader is the one who animates the action. To answer the question above, I think Generous Bosom is about this dynamic in the reading of comics – that you can pretend that you’re watching something happen both as the reader and creator but in actual fact you are making that thing happen.

I like reading comics over and over. I like that it’s a medium that allows and encourages this; it’s always easy to find a favorite scene again, because there it is. I like that in reading a comic you can go very quickly from the what to the how of a story. The density and depth of really good comics are immediately accessible.

So, this is your idea of reading comics, but what about making them? Your work finds a unique and original way to balance flow and structure, and it is very difficult to understand where you started, if from the plot or from the drawings. Glancing, a work based on the juxtaposition of wordless watercolors, could be an excellent example. What is your idea of comics and narration?

Thank you! I think my idea of comics and narration may go back to your earlier questions about water and the mysterious or irrational arriving in the everyday. Structure = The Everyday = The main narration of a comic/ consistent drawings/ Clarity, while Flow = Mystery = Water/ Change/ Irrationality.

With comics, I’m trying to get things across, to tell an actual story and to do that you have to establish rules that the reader can follow and rely on (I think this is what you mean by “Structure”). These rules start to stack up and can very quickly become impediments to freedom and to feeling like there’s possibilities in the world I’ve created which is where the energy to make more story comes from. At this sort of point it’s time for me to change the rules, insert a different story with different rules, or to maybe work on another project with different or as-yet-undecided rules.

Making Glancing felt very fun and active in this way where I made three or four drawings and then could make more drawings in between those drawings, or after them, or before. I could look at the whole thing laid out on the floor and get a feeling for it comprehensively. I want to make more comics this way.

Another reason of interest in your work is that you generally avoid the opposition between narrative and non-narrative comics – and between fiction and poetry comics – alternating the two approaches or demonstrating their substantial identity in the medium. Do you agree with this perspective?

Thank you again! Yes, I think this also relates to the answer above. I might add that decisions about the structure, whether something is “poetic” or “narrative”, etc. are made by tracking my own excitement about what I’m working on. Bringing in something mysterious/ poetic/ irrational/ non-narrative is often a solution to my becoming bored with a portion of a story or wanting to skip over a part that doesn’t feel compelling to make or to read.

Your work considers both the literary comics developed in the ‘90s and the formal experimentation diverging from the standard of the “graphic novel”, such as Fort Thunder and the output of “art comics” in general. But what is your background? And we aren’t talking only about comics, obviously.

My most important influence is the group of friends that I found at the Maryland Institute College of Art, the folks that made up the Closed Caption Comics group. We all sorted out how to make comics together at a young age. This was exactly the same time that PictureBox was starting up and a lot of the stuff surrounding Fort Thunder was coming to light and that was perfect for us – the immediacy of that work and how it was really visually-oriented spoke to us. Kramers Ergot 4 & 5, the old Fort Thunder Website and meeting CF and Brian Chippendale at SPX gave us all the sense that this was an art world that we could find a place in. And for a good while, I’d say that was about the size of the art world I cared about, it was my circle of friends and those couple guiding lights outside.

Other than that, growing up in rural Pennsylvania has had a huge influence on the imaginary worlds of my books. I also read a lot of literature. I just finished a master’s degree at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago… But are you more interested in my education/influences or in my biography?

Especially your influences, but also your biography, to the extent that it has influenced your work…

Beyond Closed Caption Comics, I’ve been involved in other collaborative art projects that have had a huge impact on my life. Shortly after school, I helped to found the Open Space gallery in Baltimore. We curated shows, held performances, established a zine library and put on a publications and multiples fair. I’m also helping to organize the first Chicago Art Book Fair here.

I was also in a band called Witch Hat for seven years which I started with Noel Freibert and Lane Milburn. Lane left the band after three years and Chris Day joined. Chris and I are in a new band called Lilac with Anya Davidson and Kenny Rasmussen here in Chicago (Chris and I moved here at the same time). When I got involved in the underground comics scene, there was a lot of crossover with the underground music scene. I met lots of musicians through comics and lots of cartoonists through music.

Do you think your art or your approach to art changed since you moved from Baltimore? Chicago has a big comic scene and a long tradition of contemporary art, we can think to Hairy Who first of all but there is probably much more we don’t know about in Europe.

My art and my approach have definitely changed a lot since moving from Baltimore. I’ve been in school the last two years, so just being exposed to tons of new work and people and ideas has been totally invigorating and overwhelming. I think I’ll be digesting all of it for years to come.

On a basic, lifestyle level, moving here and attending school has allowed me to stop working a non-art-related day job (at least for now). That’s a great gift that I didn’t previously think was within reach for me. I think I’m now more dedicated to the idea of trying to make, or at least to make and to teach, art full time.

As for Chicago, it’s an amazing city for cartoonists. There’s a beautiful supportive community and stuff like the Zine Not Dead reading series run by Matt Davis and Brad Rohloff which carries on the tradition of performative comics reading started by Lyra Hill with her Brain Frame series. I mean just in my neighborhood I’m about five blocks away from a house where Anya Davidson, Lane Milburn, Margot Ferrick and Andy Burkholder all live (Edie Fake used to live there in the attic). A couple blocks in a different direction are my dear friends Molly O’Connell and Chris Day – both of them with beautiful diverse practices that include but aren’t limited to comics and bookmaking.