Herb Trimpe was one of the most important artists at Marvel Comics in the ’70s, mostly known for his work on the series The Incredible Hulk. Trimpe died on April 13, 2015, after completing a story for All Time Comics, a new line of books created by New York-based cartoonist Josh Bayer, editor of Suspect Device and author of comics as Raw Power and Theth. Bayer is a huge fan of Marvel comics from thirty-forty years ago and he also created his own bootleg stories, starring Rom, Conan and the cartoonists of the Marvel Bullpen, often denouncing the way creators as Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and Steve Gerber were treated by Marvel industry. Some scenes from his comics include Steve Ditko screaming “Marvel and Disney… are the government!” and a girl surrounded by Deathlok, U.S. Agent, Howard The Duck and other characters saying “Face it. Around here, we’re as disposable as the pencilers, inkers and writers who make up the Marvel Comics industry itself”.

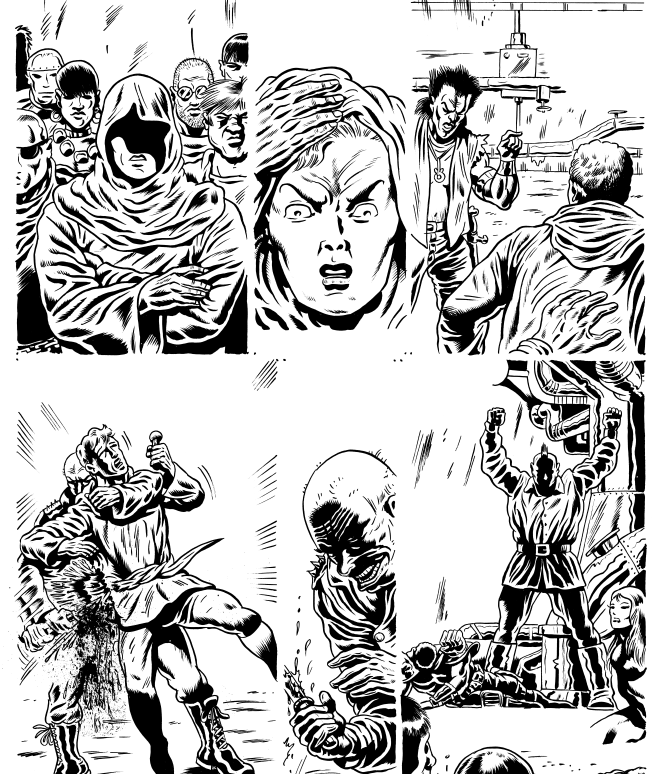

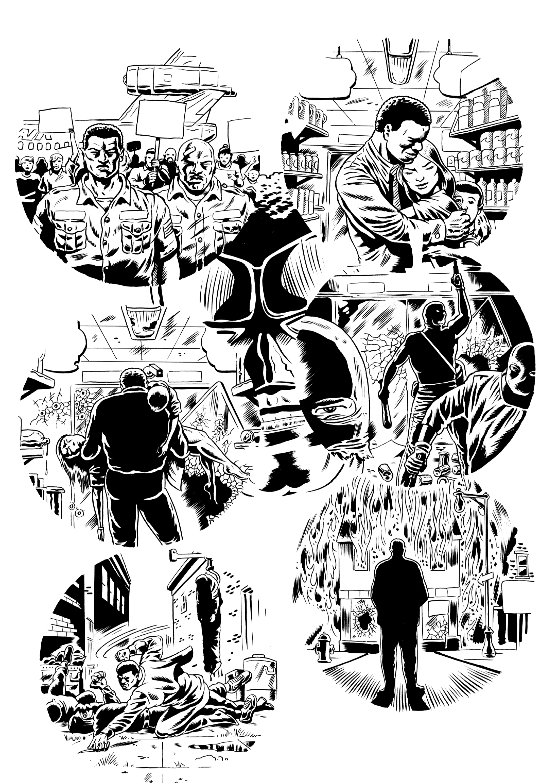

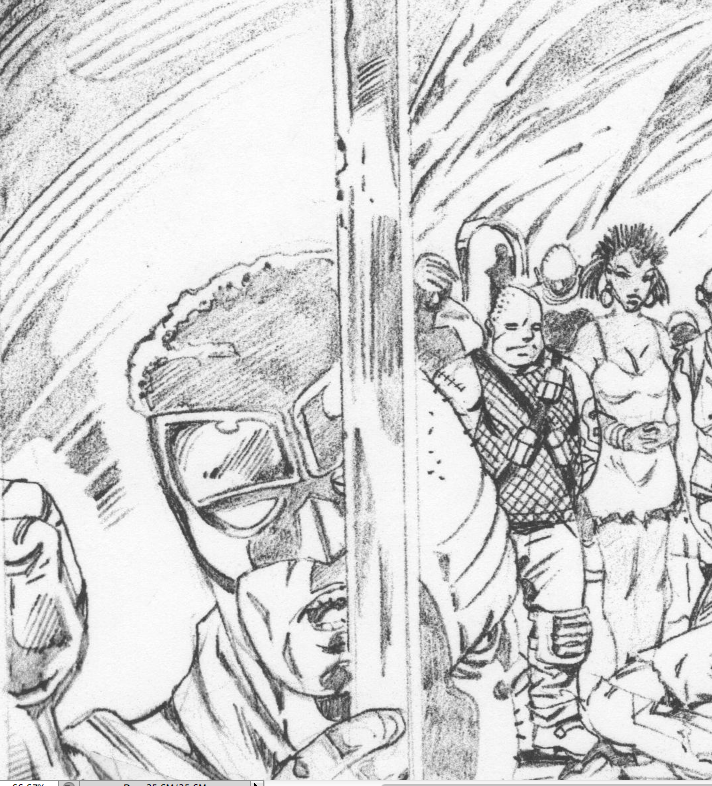

This is how Bayer remembered Trimpe on his Tumblr. All the pictures are from Crime Destroyer Giant Size by Josh Bayer, Herb Trimpe and Benjamin Marra, due out by October 2015.

“Last year I contacted Herb Trimpe and asked him to draw a book for a line of comics I’m editing and writing. We were able to offer him a decent page rate and astonishingly he said yes and I’ll be publishing later this year what is (as far as I know) his last comic. Trimpe’s work was everywhere when I was growing up, in reprints and in current books on the stands, and his swaggering, cartoony, monolithic, half-rickety, half-fluid characters were ubiquitous with what I thought comics were. He maybe was one of the first people I saw who liked to make his characters WIDE, the chunkiness that is so fun for cartoonists to express (everyone from Frank King to Crumb to Gary Larson is part of this tradition) is intact in Trimpe’s pencils. The mouths were wide, the faces were wide, the fingers were wide. He was a Kirby protégé and was smart and humble enough to be proud of his ability to swim alongside his heroes without seeming to aspire to greater heights. It seemed to be fulfilling enough to be a steady artist, a provider for his family, a vet who served in Vietnam, and a deacon in his church.

Kirby was a leader, and Trimpe was like a soldier, but as much as he might have recognized himself as merely a professional, skilled at drawing everything from technical equipment to horses to architecture to sweeping urban panoramas, he wasn’t merely a dependable illustrator. He also drew with the inventiveness and enthusiasm of a kid. A freedom that many artists will never have. Looking at his work, you know his personality as much as you know R Crumb’s. It’s warm and familiar. The correspondence he creates between the reader and the work is more like Crumb or Basil Wolverton than many of his slicker, smoother peers. And like Crumb, his stuff might reflect the real world at times, but it’s never gonna let you forget it’s a cartoon.

As photocopies of his new pages began to arrive in my email last year, I was so heartened that in his seventh decade he was doing such peak work, full of the transitions, lighting and sequencing he was known for. “I have to tell you, I’m having a ball… it’s the most fun I’ve had doing non mainline work”, he wrote to me, and I was so glad. I would be happy for days every time I heard from him. I kept looking at the work. The lines were confident and powerful, his storytelling brimming with the sort of visual inventiveness that results from having completed thousands and thousands of pages of work before we connected.

To me, getting approval from him, and from other professionals like Rick Parker and Al Milgrom, has been everything I’d hope for in comics, a seamless circle between the past and future. Only in a lopsided industry like this one could someone in my position at the low end of the ladder attract a string of creators with decades of experience and accomplishment behind them.

Trimpe’s work helped to keep the American industry afloat, in a very visible way. He was one of the top six artists at Marvel and one of the most steady and visible. He slowly was eclipsed by younger artists, but his contributions were undeniable and should have set him up for life. Last year, a page of art appeared on the market by a collector who had been hoarding it for 35 years, the final page of Hulk 180, showing the first appearance of Wolverine, which was inscribed to the collector by Herb. Apparently it had been given to the collector by Herb himself in 1983. The art resold for over 600,000 dollars, breaking a record for original comic art sales set a few years prior by a Frank Miller Batman page. The collector had said he was going to give a large portion of the money to an organization for older artists and I’d been hoping he secretly was going to give the money to Herb Trimpe to counterbalance the way he never took part in the massive profits his life work generated for the industry. I don’t know what the result of the sale was but it would be so satisfying for Herb to know his work had brought about a long term security for his family that was the dream of almost everyone in his generation.

A lot of my own comics are about creators of the past. I’ve always been fascinated with how people face age and the changes life brings on in its third act, and the difference between the face of public figures and their interior life. I’ve done stories interpreting a fictional version of the Marvel Bullpen, showing my versions of Steve Ditko, Bill Mantlo, Bill Everett and Stan Lee, and mostly they are protest cartoons about the way creators are treated as disposable. The whole time we worked together I wondered if Herb ever saw the comic I did about him, “Trimpe Survives” (earlier published as “Trimpe Loses”), that I did in 2011, a year or two before I contacted him. I kind of doubt it, but you never know.

It detailed a metaphorical battle by Herb to stay alive in a barren wasteland, surrounded by flesh-eating Image Comics-style adversaries. The comic ends with Trimpe, determined to outlive the younger predators waiting on the horizon and drawing, (as he did in 1992), an issue of a Fantastic Four Unlimited in the style then made popular by his younger competitors. This instance of a creator of his stature attempting to stay current when work was disappearing is just wrong. I never forgot it.

When we began to collaborate, I was afraid he’d think I was making light of a painful period of his career, and that I was taking a shot at him. I never broached the subject. The vibes were running positively and I didn’t want to screw it up. But I’d always thought I would eventually get a chance to tell him how much admiration I have for him, how his career is a testament to the triumph of personality over slick modernization.

I never wanted to explain that I meant no disrespect portraying him as a man whose head was attached to Godzilla’s body, since that could have been seen as a jab at him, you know, the “old dinosaur” of comics. I was responding to the portrait of himself he’d etched in his article in the NY Times, in which he described a world that had left him, at age 56, seemingly condemned to obsolescence. It seemed traumatic but I thought he fought back with resourcefulness, self-reflection and bravery, and I always wanted to tell him. But I thought there’d be time later. Clearly Herb had many, many good years left in him.

Man, I’m so consumed with loss right now. I’ve been sad all week. I never met him, but I feel like I’ve lost a friend”.

Josh Bayer, April 18, 2015