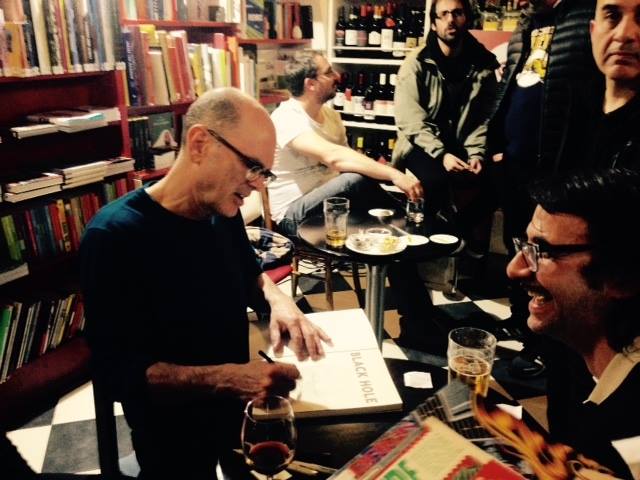

On Thursday 19 March Giufà Bookshop in Rome hosted a panel with Charles Burns. Black Hole‘s creator came to Italy to accompany his wife, artist and painting teacher Susan Moore, just as he did in the Eighties, when the couple spent a few years in Italy and Burns joined the Valvoline group (he spoke about this experience in this interview with Darcy Sullivan). The evening was an opportunity to introduce the American cartoonist to Italian readers, deepening his creative process and the themes of his comics. Novelist and journalist Francesco Pacifico translated the conversation while comic critic Alessio Trabacchini and Italian cartoonist Ratigher asked the questions. At the end of the discussion, Burns signed and drew sketches for hours, showing an extraordinary willingness. I’ve translated and sometimes summarized the questions, whereas Burns’ answers are (more or less) his original words.

Alessio Trabacchini: Charles Burns knows how to tell complexity. He found a narrative form and a line to tell the ambivalences of feelings and of the entire world. I would like to ask how he managed to tell a particular aspect of human life, the one related to sex, sexuality, beauty and desire. In Black Hole there are some of the best representations of sex ever seen in comics. So I’d like to know his approach to this aspect of human life and to its representation.

Charles Burns: When I finally reached the point in my life where I felt comfortable about expressing something very personal, I wanted to be as free and open as I could. Sexuality is in everybody’s life but I didn’t want to do something that was purely gratuitous, purely pornographic. I wanted it was a natural part of the story. So, for example, in Black Hole there is a very strong scene but the entire story is not gratuitous, is not about provoking someone or making something that is titillating. I like the idea that in a three-four hundred pages story you would have ten pages focused on something that is very strong. There are moments when I was writing stories that I felt like “I don’t know if the world needs to see my vision”. It seemed too dark to me sometimes, but I wanted to be as honest and open as possible. I think in earlier works I wasn’t aware of it but I know that I was censoring myself, stopping myself from ideas that were very strong and maybe disturbing, but I tried hard to push that away, to make something strong and honest… And if I’ve to be honest I’ve never met a woman with a tail…

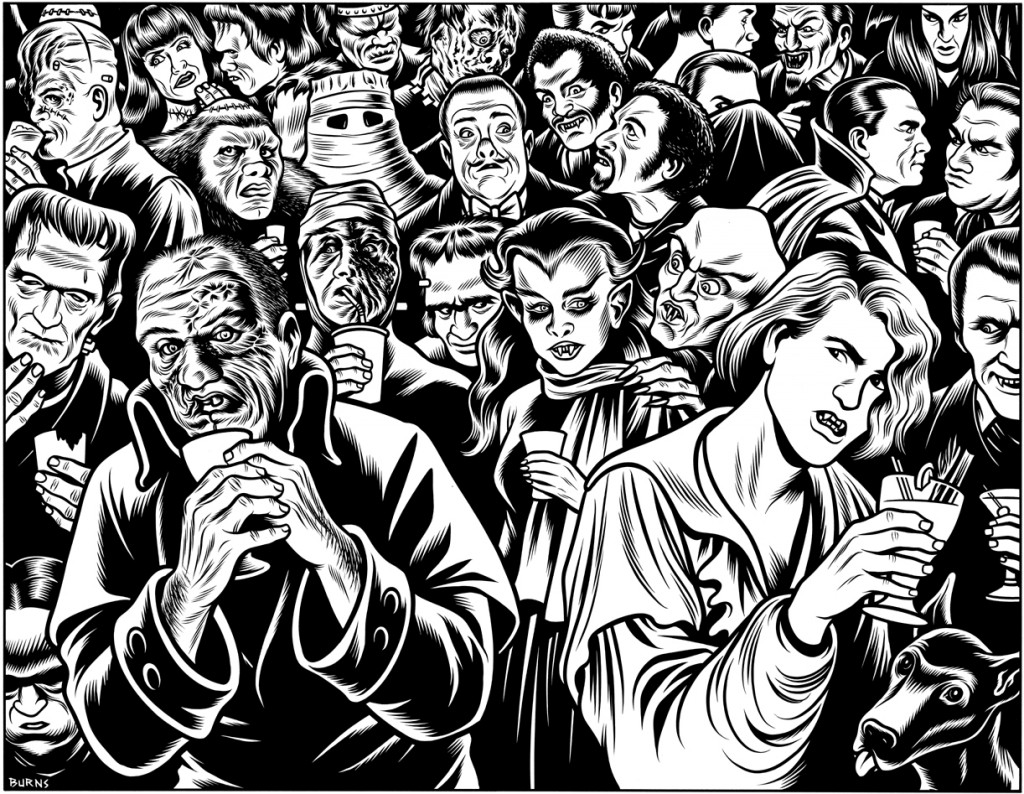

Ratigher: My first question is similar but on another aspect. I consider Burns the cartoonist who depicted the occult and the bizarre better than any other. He’s for the comics what is Lynch for the cinema, they are the keepers of mystery and nightmare. I’d like to know if he thinks to have reached a new level over the years, if he had an evolution like in the role-playing games, from an occultist – a fan of bizarre and dark things – to a wizard with the power of frightening people, making books with dark forces inside.

Burns: I find that my stories for whatever reason move toward the darkness, but I’m not intentionally trying to scare someone. Growing up I was attracted to a darker side of America, an underside of American culture. There is a facade that I grew up with where everything is ok, but underneath that sometimes there is a dark underside. I was always interested in that facade and what it represented. And I was interested in reality, the reality I grew up with, the reality that I felt and that had nothing to do with the status quo and with the normal vision of a happy and secure family. None of my stories is very happy.

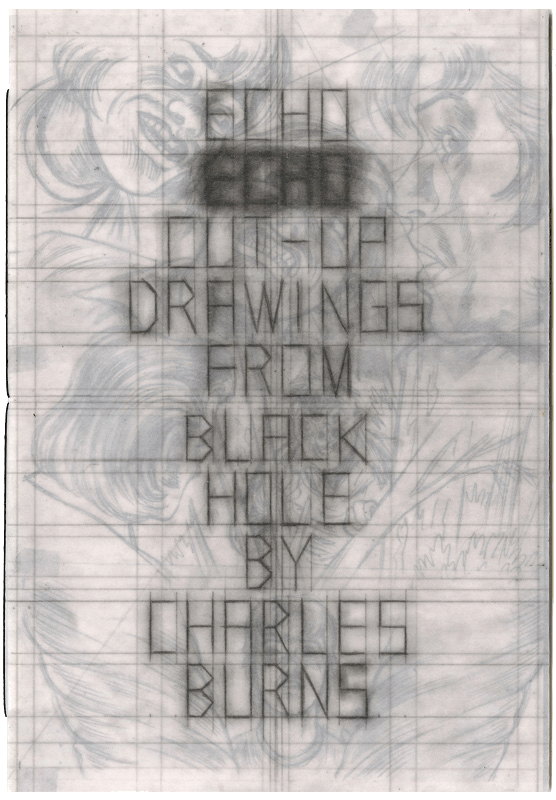

Trabacchini: Another thing I’d like to ask is about the line. Your style is very sharp, with strong contrasts of black and white. Even if there are a lot of shadows, it seems a personal version of the French ligne claire, an explicit reference in your last trilogy, where you created a dreamlike world that is a sort of mash-up between William Burroughs’ Tangeri and the setting of Herge’s The Crab with the Golden Claws. Then I was looking at this one again (Echo Echo, a collection of preliminary drawings from Black Hole) and it’s interesting because it shows how you arrive at your ligne claire, with a series of lines, marks, sketches. And this strong and instinctive way of drawing becomes the restrained and well-defined style of Black Hole, so distinctive to remain coherent and uniform in ten years. The pencils of Tin Tin have this same peculiarity, they’re full of marks and crossed lines but then they come to something clear and precise. I’d like to know how Burns works to create his own line.

Burns: I think my work was emulating ’50s and ’60s American style I saw very early… Harvey Kurtzman, Mad Magazine…. There is this style with very thick, beautiful dark lines. On the other side of that, it was a very unusual situation for an American of my generation to see Hergé and his beautiful ligne claire, the colors, the characters… So, I was always very attracted to Hergé and the clear line, but my style definitely makes towards this very dark line with the brush. It’s been pointed out to me that when Hergé was drawing he had this very rough, open line. He started with drafts and then distilled, distilled, distilled down to a very specific line. The book you’re showing is a collection of preliminary drawings, some are very clear but some are more rough, very gestural… They start from a very gestural idea and then are refined and refined as I work.

Ratigher: I also have a question about the style. I think his drawings show a high technical ability and this is one of the reasons a lot of people like his work. But his illustrations are also narrative, he doesn’t draw to show off his craft, every panel tells a piece of the story. Even when he draws a face, the reader can imagine the life of that person. I’d like to know if this is true and how he worked on it.

Burns: For me comics are all about the story. I know that people look at my work and say “look at this line, look at the drawing ability” or something like that, but the story is always most important. Telling a story is a distillation, it starts with something very draft and refining, refining, refining. There are moments when I want to draw a beautiful picture but if that beautiful picture is not part of the story I can’t put it in the comic.

Ratigher: But I’d like to know if this was a natural and innate skill or he had to reason about it, because it’s rare to find artists that are so technical and also narrative. Perhaps only Robert Crumb has this kind of control on his drawings, always detailed, elaborate but also devoted to the story. I don’t know if Burns had to work on this aspect of his art or if he was born with this ability.

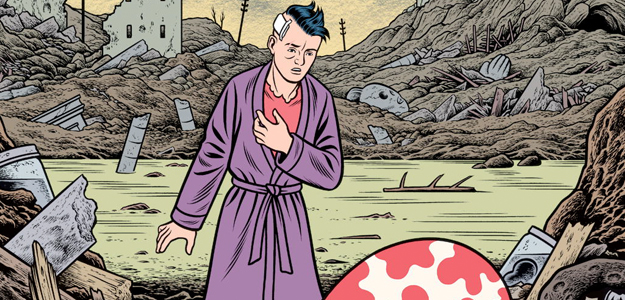

Burns: I was born with nothing… “niente”. I think there are cartoonists that start on a very visual side and cartoonists that have a very literary side. I started with the visuals and I needed to teach myself the language of comics to tell a story. I’m turning sixty this year and I still don’t understand it… But I’m trying. When words and images come together perfectly, the images become invisible. You’re IN THE WORLD, you’re not thinking to technique, you’re not thinking “oh, this is a beautiful line”… You’re immersed. It’s the same way with the good movies, with the good novels, with anything. The techinque becomes invisible.

Pacifico: At this point I’m asking if you can give us some examples of movies or novels where the technique became invisible. I’m thinking about the latest movie by Paul Thomas Anderson, Inherent Vice, where it seems he deliberately wanted to delete the idea of a director that shots big and structured scenes to make us feel only the plot.

Burns: It’s always impossible for me to point very directly to influences but I can talk about the technique, the lines, the look I liked in some specific comics. Actually I could be influenced by everything. In my case I’m trying to do my best to tell my story, it’s not Ernest Hemingway’s story or Nabokov’s story, or Murakami’s story.

Ratigher: But what I’d like to know, coming back to my latest question, is if Burns sometimes sits down and draws something that isn’t a comic, that isn’t narrative. If it happens sometimes he likes a flower and decides to draw it.

Burns: I would love to do that, but no. Unfortunately it is a slow, slow process. For example, my friend Chris Ware told me he has a large sheet of paper and he starts drawing. This is impossible for me. I have notes and notes and tiny drawings and everything. There is nothing natural about my process. It’s very slow. I think my life would be much more simple if I had this direct approach but it’s not possible.

Valerio Bindi (Italian cartoonist and coordinator of Crack! Festival): I remember Gilles Deleuze said about Lewis Carroll that he was wide but not deep. I think Burns is both wide and deep, because he accurately builds the structure of the story, that has many layers – adolescence, wood, metaphors, dark places – but at the same time his drawings are fascinating for everyone, and this makes his art wide. For my generation of cartoonists who started making comics in the ’80s, he is the artist who took the themes of ’50s and ’60s in the underground, creating a cold, clear and synthetic style. Now I think the underground has moved from Usa to Europe and that people from Usa are mostly following the European underground movement. I’m asking what he thinks about it, if he sees an underground today and if yes where he sees it.

Burns: For me, growing up, my sense of underground was being thirteen or fourteen years old and discovering Robert Crumb and comics that moved away from the commercial world, something vey self-expressive. I think early they were transgressive because they had to deal with sex, drugs, politics. I think now it’s established that you can write something very personal and it doesn’t have to fit in a genre… I don’t know if the world of underground comics ever existed. Underground seems very inaccessible but for me, growing up, I could take a bus and find a store and get every Zap comic, Robert Crumb’s comic, every hippy comic and later every punk comic. I like the idea that someone who is in his twenties has no idea who Robert Crumb is, has no idea who I am, looking at something new, moving in other directions. There is no need to know the classics. I’m not interested in a young artist who talks about his influences. It’s a pleasure when everything moves on… When I was younger I remember Art Spiegelman, my close friend, saying that we had to move past Will Eisner. The underground is someone seventeen, eighteen, ninetheen, twenty years old who has never heard of me.