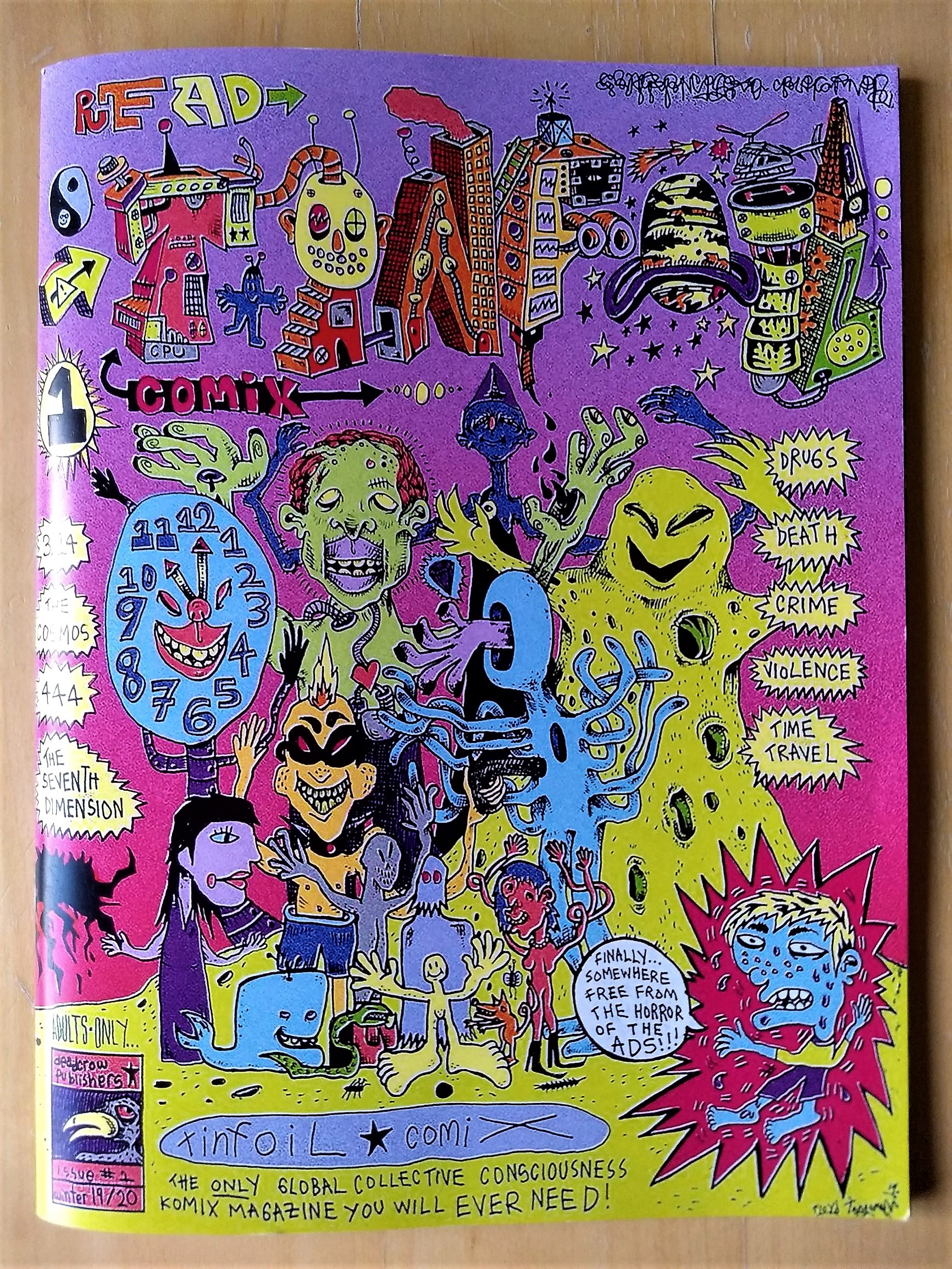

A new anthology coming from San Francisco, Tinfoil Comix showcases mostly unknown cartoonists but beats a lot of similar and much more renowned efforts. I haven’t seen for a long time such a combination of talent, strangeness, urgency and lucidity in one shot: almost all the artists in Tinfoil know what to do and how to do it, they have something to say and they aren’t smooth talkers. The comics show varied themes and styles but have substantial points in common. The first that comes to mind is an unusual attitude towards everyday life, exemplified in a sequence by Jade Mar: “Everything was one/We ate things/We farm things/We wait in lines/We advance/Were all these screens always here?/I’ve moved into this cave. The rent is incredibly affordable and/I feel at home”. The drawings are simple, indie and childish at the same time. And Mar insists a few pages later: “I can only tell a story from my perspective/I could try to tell one from yours but/I don’t think it would feel right”.

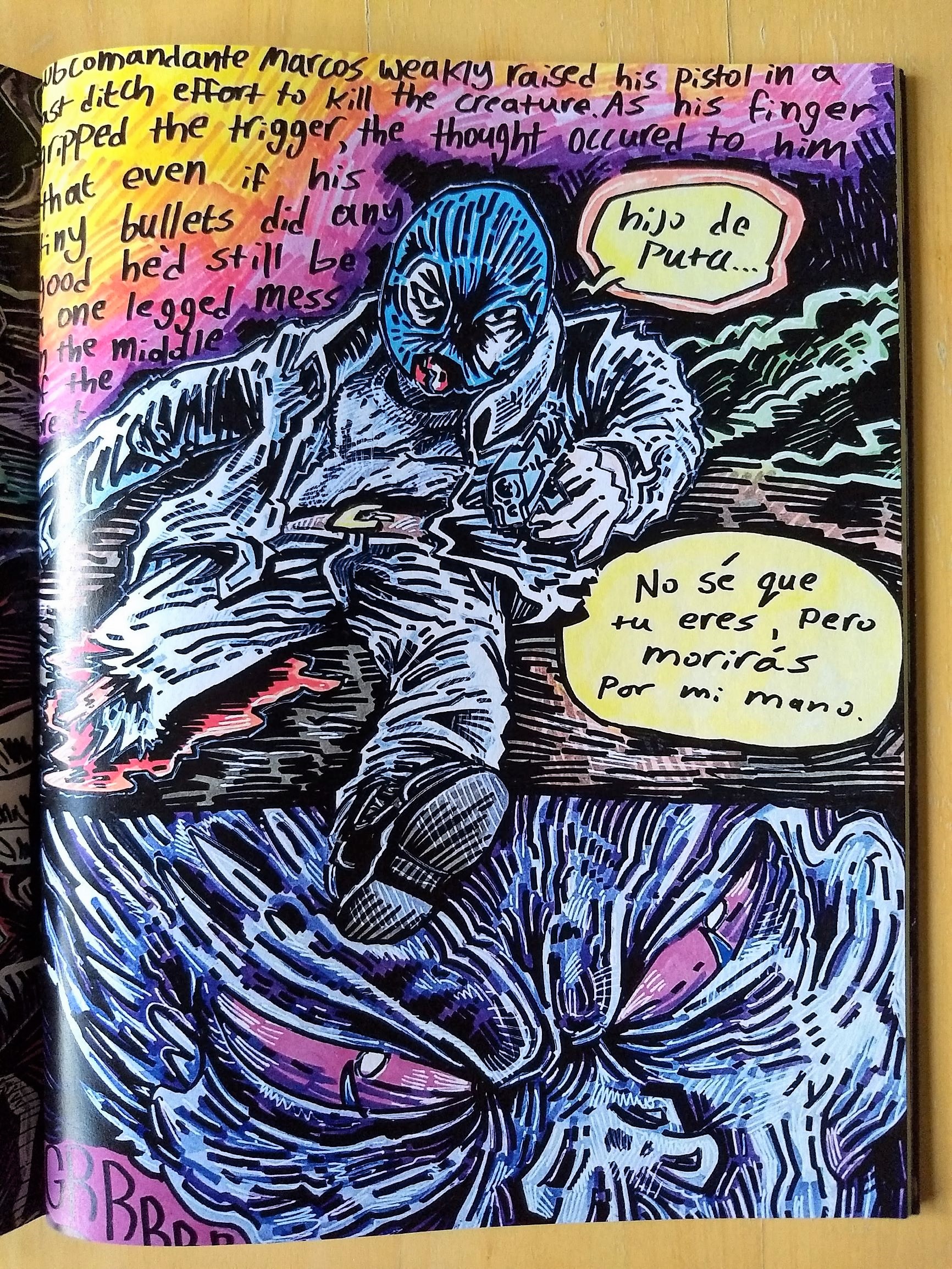

Tinfoil tells stories from the author’s point of view, and if this is obviously true of everything, it is particularly true here, because they are defined, strong, raw perspectives. Perspectives different from any others, often influenced by drugs or pills, as in the slightly retro contribution by Fried Feet that opens the book, or which portray altered states achieved through suffering, as in the case of a powerful five-pager dedicated by Virgil Warren to Subcomandante Marcos. Warren’s art is made of thick black lines that scratch the colors to create a ’70s look that would easily fit in an All Time Comics floppy.

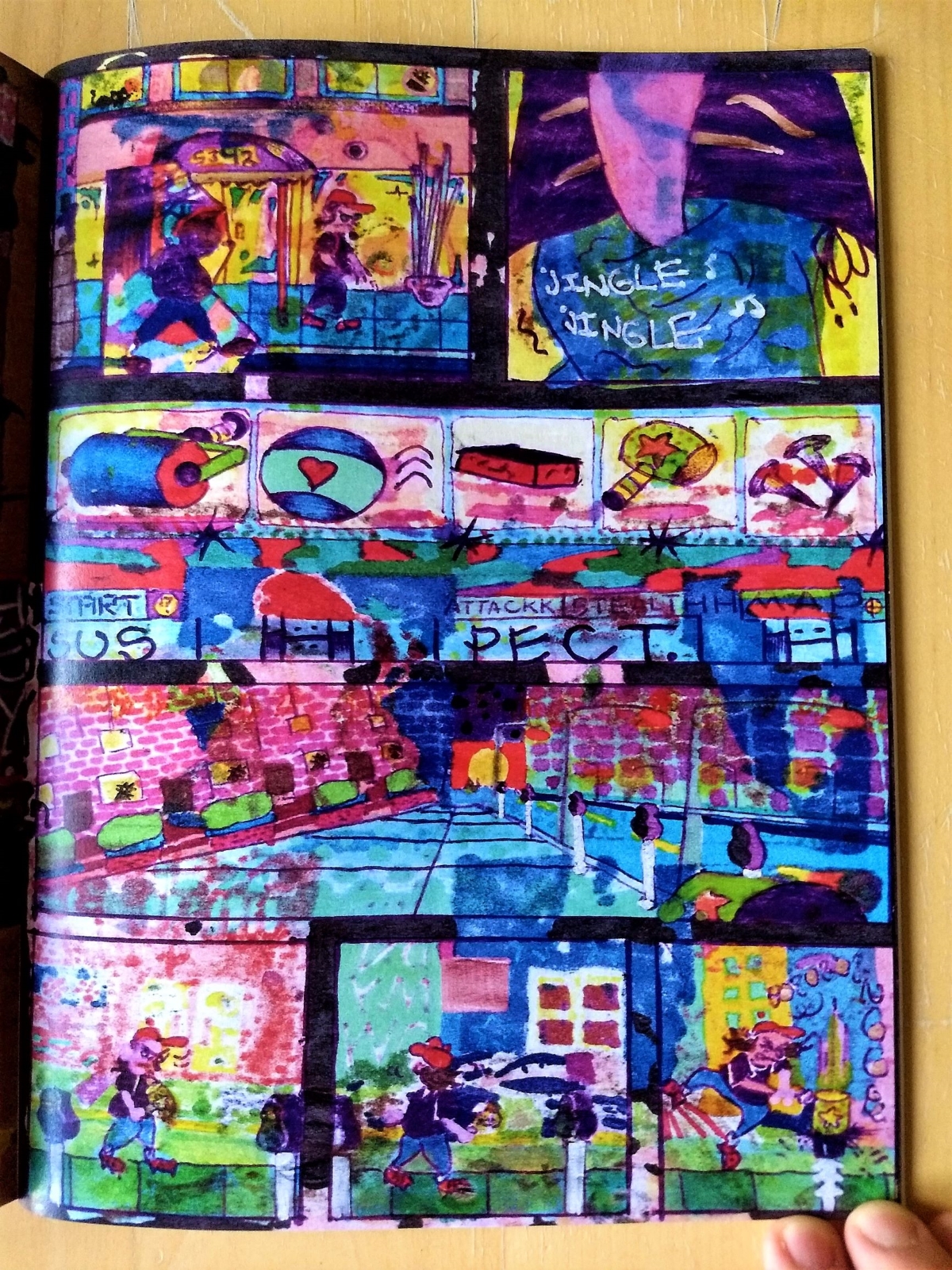

Sometimes the pagination isn’t perfect and so we miss the edges of Hope Kogod’s comic (and someone else’s too). Kogod’s two-pager opens vertically and look likes a poster. At the end the author states: “It’s 2020, I deleted Instagram, email me”. Tinfoil‘s artists are old school, so that it’s difficult to track them on the internet. These stories don’t talk about the “virtual” but are mostly about the “real” world, and in fact there are many urban-themed comics, such as the four-pager by Nick Fowler, influenced by Bill Sienkiewicz, and the colorful Jeremy McBrian’s contribution, inspired by graffiti and video games. Editor Floyd Tangeman uses a lot of colors too, and, in order to take nothing for granted, reminds: “This comic reads from left to right”.

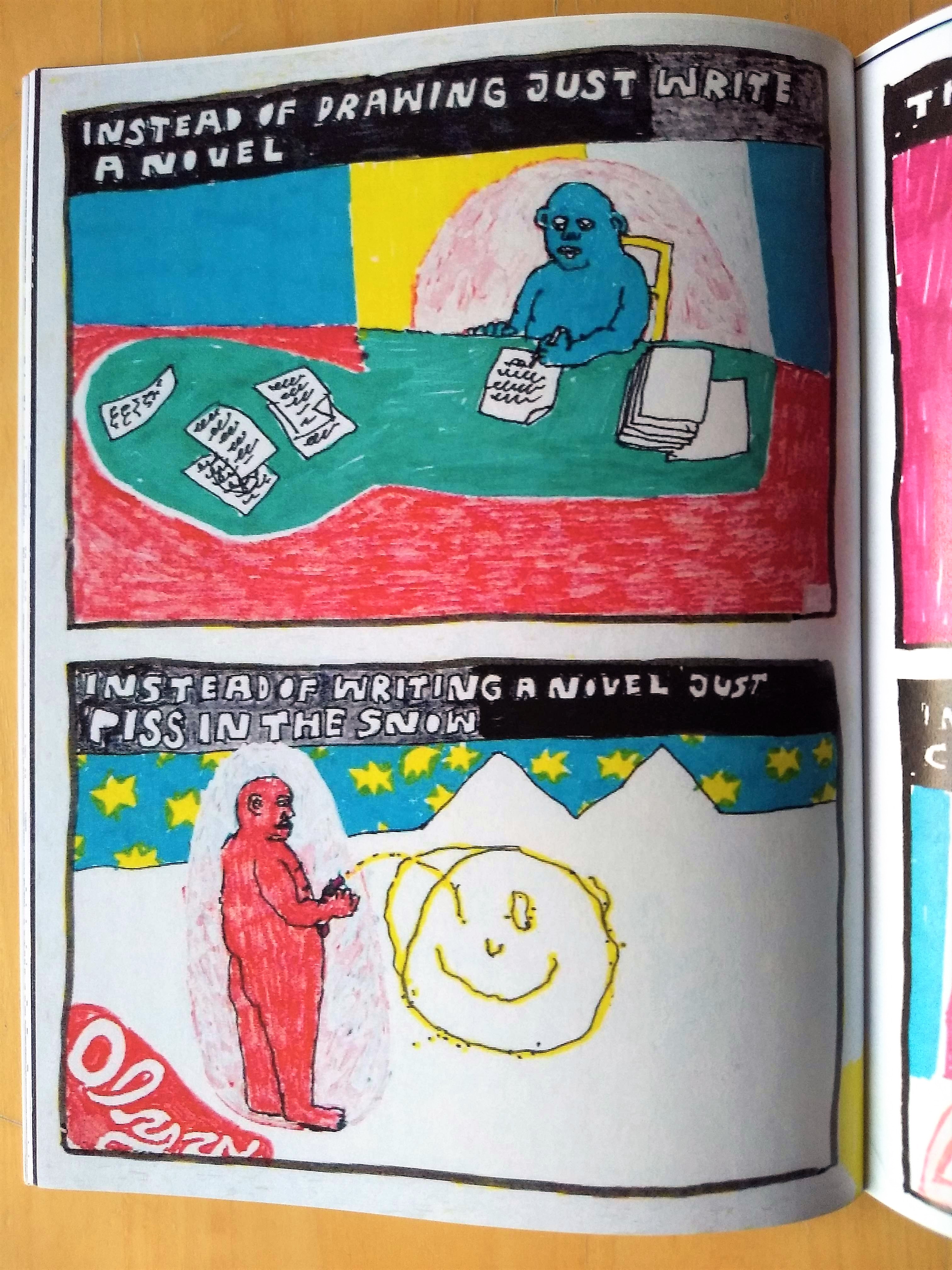

These cartoonists don’t look at contemporary comics as a reference point but mostly use a naive attitude, as that of outsider artists. The effect is refreshing, because for once we are not dealing with the copy of a copy, whether it’s of Olivier Schrauwen, Jesse Jacobs or Tara Booth. The feeling is they have more to do than stay home reading the latest comic from Fantagraphics. And from these pages it comes exactly this, an incredible and unstoppable and irresistible urge to DO. In this sense Olga Corcilius creates the perfect manifesto using simple colored markers: “Instead of drawing just write a novel/Instead of writing a novel just piss in the snow”. And the drawing appears on a white background, a few yellow lines shaping a smiling face. Are we witnessing the rise of a new revolutionary generation of artists? This is the first impression, and I hope that next issues (the second is already printed) will provide some confirmation.

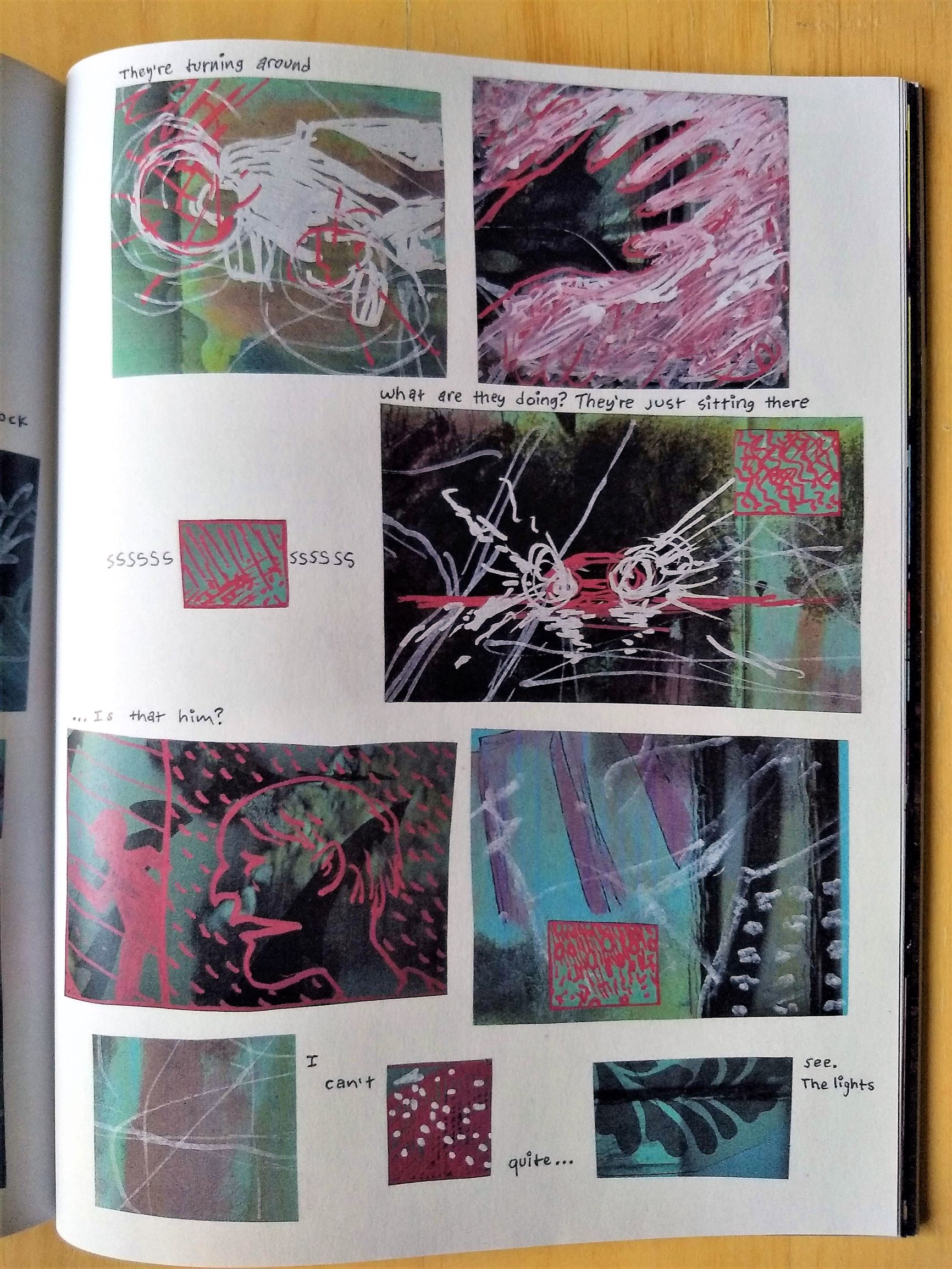

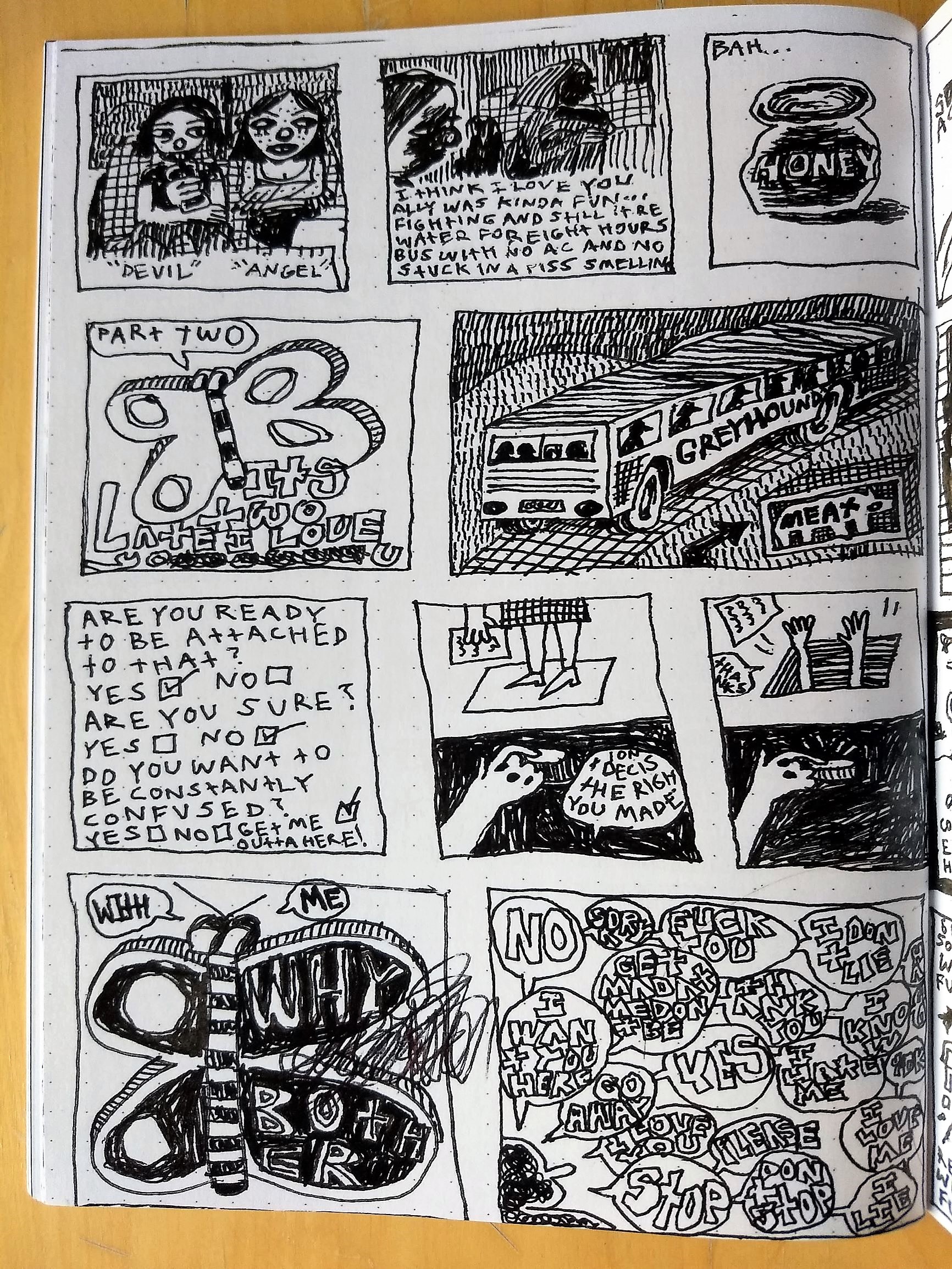

The comics follow one another seamlessly, there is only a list of cartoonists in order of appearance in the inner sleeve, like Sammy Harkham used to do in some issues of Kramers Ergot: it’s our job to understand where one ends and the other begins. Around the end here comes Lemonhed, whose work can recall in some way that of E.A. Bethea, an artist well known to the readers of this website: small, square panels that alternate drawings and text only.

If the comparison works for the layouts, it doesn’t fit for the language, which is not poetic in its very own way like in Bethea’s art but it’s rather autobiographical, although it sounds always nervous, like it can’t focus on a particular topic. The writing digresses, breaks down into simple letters or numerical series, and the drawings are like doodles, until the author confesses: “So heres the thing the year is two thousand and nineteen I was gonna do my laundry but instead I/took some Adderal and decided to make this comic so that maybe I can figure some things out”. Comics become a therapy, and perhaps Tinfoil Comix is a therapy for all its readers.

Tinfoil Comix is created by Floyd Tangeman, who is also the editor of the magazine with Virgil Warren. Some copies of this first issue are available in the Just Indie Comics webshop.