There have always been record labels that defined a style, combining a specific genre with very distinctive aesthetics: Factory and Sarah Records are a couple of examples, though I could offer a lot more. In comics, this phenomenon can’t exist in the same way; if it’s difficult to demarcate boundaries between one genre and another in music, it is almost impossible to do so in an art form as articulate and complex as comics. The usual distinction made in the US market distinguishes between general or mainstream comics and “indie” comics, with mainstream comics linked economically to large corporations and aesthetically to contents appreciated by the mass public, and indie products made outside mass production. It goes without saying that the indie world should also convey different contents from those of Marvel or DC, but this isn’t really the case, because independent labels like Image are giants that publish a lot of comics that are far from revolutionary or unconventional. In comics, “indie” and “alternative” are no longer synonymous, and to find things that are truly different we have to explore the underground, that is no longer a genre born in the 60s and characterized by the satire of the status quo and by the presence of sex, drugs and various obscenities, but an “underworld” of small publishers that is more and more fruitful and interesting in the North American scene.

One of these small publishers is One Percent Press, a label that not only publishes comics without worrying about eventual commercial success, but that also does its own thing according to the modus operandi of a record label of the past. So it isn’t a coincidence if the brand founded in 2004 by Stephen Floyd and JP Coovert publishes and distributes not only comics but also LPs and CDs of bands such as Wooden Waves and Tin Armor, in a spirit that takes its cue from the Do It Yourself philosophy. And they do it with a reasonable continuity, since the two have released over 50 comics and 25 albums in the past ten-odd years.

To define the “sound” of One Percent Press comics is neither the package, which differs from comic to comic, nor the clean lines of the drawings, even if this is a recurring feature. The point of contact is rather the subject matter, since most of the books are a reinterpretation of the coming-of-age genre, exploring the concerns of children and adolescents or showing people in their twenties and thirties who still are looking for their place in the world. In this sense, the book to better understand the idea behind this editorial project is Salad Days by JP Coovert. Brandon comes to Minneapolis to meet an old friend and spend a weekend of “movies, videogames, and pizza”. One is forced to wear a tie for his work as a designer in a corporation, the other still doesn’t know what kind of career he would like to choose. Both have family and have to face the consequences of growing up, included the fact they now have little time to devote themselves to their passions. The memory of past times drives them to get out of the usual routine, to do something different, so that they end up chased by a police car.

I don’t know how many autobiographical elements are behind the angular lines and the essential drawings of Coovert, but one of the two characters could be the author himself, wishful to stay true to the dreams of his youth. Moreover, the history of One Percent Press is more or less this: that of two guys who met in their twenties and have created this micro-reality to keep in touch and do something together, even though they’ve always lived in different cities (the label is currently located between Buffalo and Minneapolis). As for the name, One Percent Press refers to the fact that only 1% of life is truly excellent, only 1% of food is very good and only 1% of comics and music is really noteworthy: a concept that, according to the same Stephen Floyd, is typical of twenty-somethings, of young people seeking their way not so much in the world, but against the world.

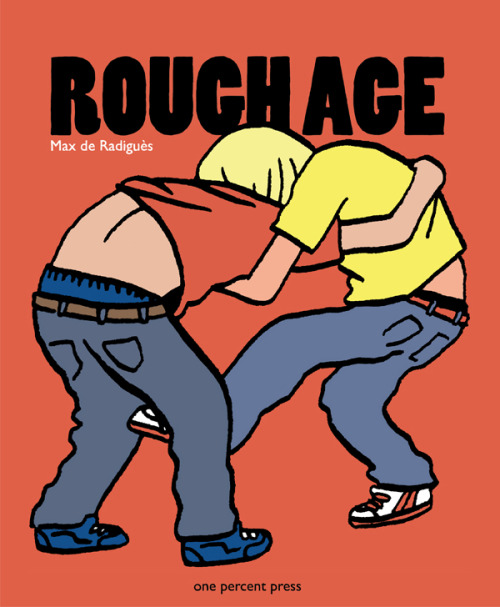

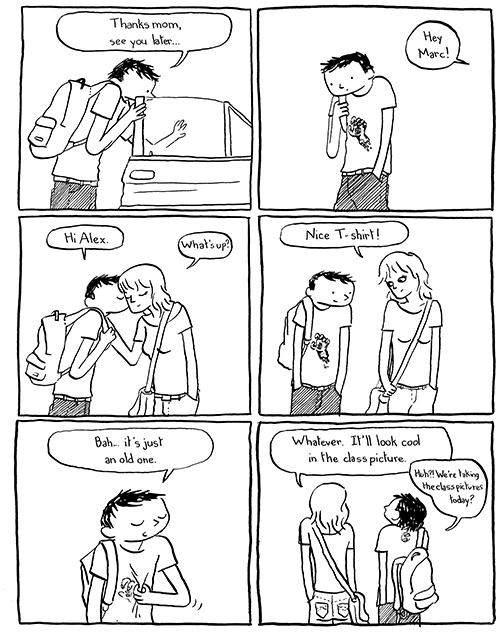

The most important release to date is the English version of L’Âge Dur by Max de Radiguès, translated under the title of Rough Age, which unfortunately loses the wordplay of the original. But the content doesn’t change and so the American readers can enjoy in this 128-page book from 2014 the original zines self-published by the Belgian cartoonist between 2009 and 2010. The style is clean on the surface but nervous underneath, and it shows deviations from the reassuring forms of ligne claire, as if the shakes of the pen reflect the concerns of the characters, schoolchildren who think above all of relationships with the opposite sex while they argue, fight, copy homework and gossip about each other. The different plots intertwine, and a lot of characters stand out: Roman is mocked by a classmate and invents an imaginary girlfriend, Gary has an affair with Louise but is secretly in love with Marc, Ron breaks up with his girlfriend and shows indifference while suffering in secret. Lightly we reach the conclusion, when the boys have to pose for a class picture with broken noses, sullen faces and black eyes after all that has happened in the pages of the book. Rough Age is in many ways a classic French-Belgian bande-dessinée, but the minimalist approach recalls American indie comics. In the end it comes out a universal story that could tell the life of children from much of the Western world.

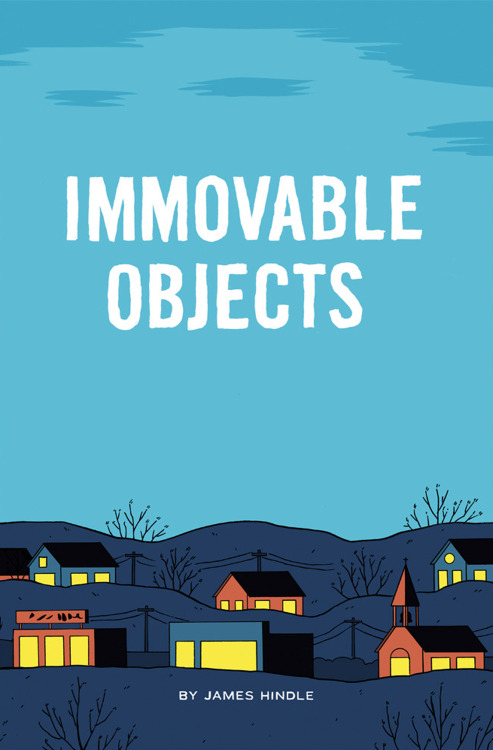

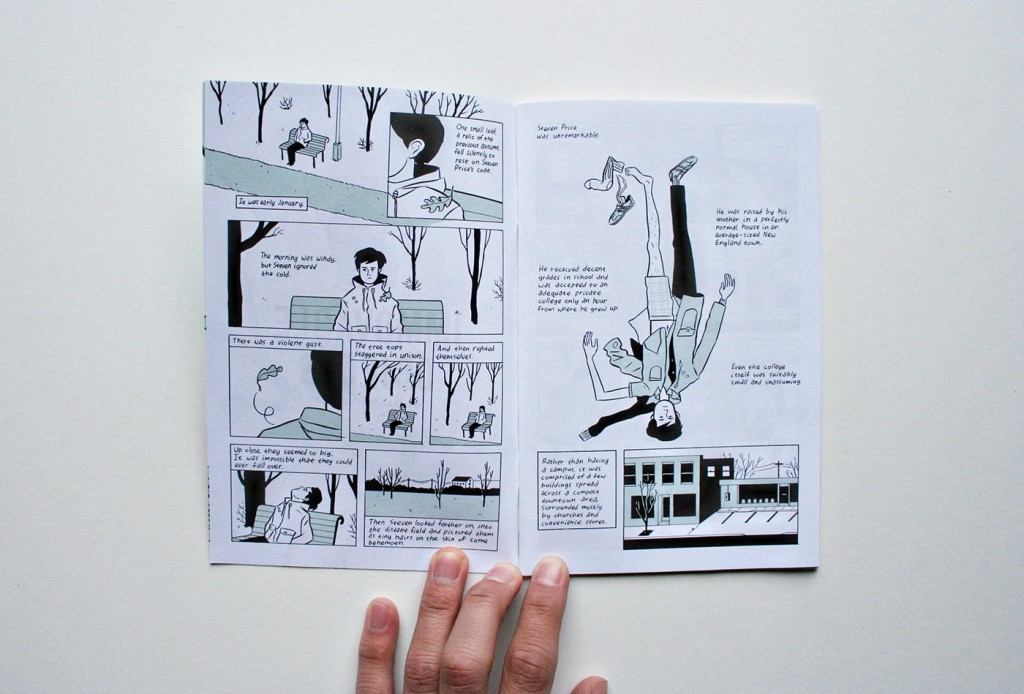

The One Percent Press book fitting perfectly in the coming-of-age genre is Immovable Objects by James Hindle, an author whom I already knew for the brief Yellow Plastic published in the fourth issue of Irene anthology (my review is here). The two stories have different points in common, since both make extensive use of voiceover in the captions to tell a relationship between a very awkward boy and a troubled girl smarter than him. Here in particular we follow the ordinary adventures of Steven Price, an “unremarkable” boy, “raised by his mother in a perfectly normal house in an average-sized New England town”. Steven “received decent grades in school and was accepted to an adequate private college only an hour from where he grew up”, a college that was “suitably small and unassuming”. Isolated from school friends, lonely, contemplative and with the recurring thought of a father he never knew, Steven is initially depicted sitting alone on a park bench, while tree leaves fall on his shoulder. Things change when he meets Caroline and builds with her a confidential but lacking of any sexual implication relationship. As often happens in these situations, the friendship falls apart when a third person comes into play, in this case a professor of drawing to whom Caroline is increasingly attracted. Jokes and winks give way to jealousy and repressed desires, so that Steven is forced to overcome the easy support of the relationship with the girl to look inside himself, become more confident and perhaps mature.

Like the aforementioned Coovert and de Radiguès, Hindle has a simple and clean line, although more round than that of his colleagues. Immovable Objects presents a lot of interesting graphic solutions, often obtained with the juxtaposition of black, white and light green. Steven’s mother is depicted by a white shape with black outlines: she is a background character, so she isn’t defined as the protagonists. Even the father figure is undefined, but this time is completely black, even more mysterious. And when the story reaches its conclusion the figure of Steven becomes blurry too, made of light green. The circle is closed and also the main character can become a vague shape. Yet Hindle managed to make him familiar to us in these 36 pages, providing a deep and nuanced story.

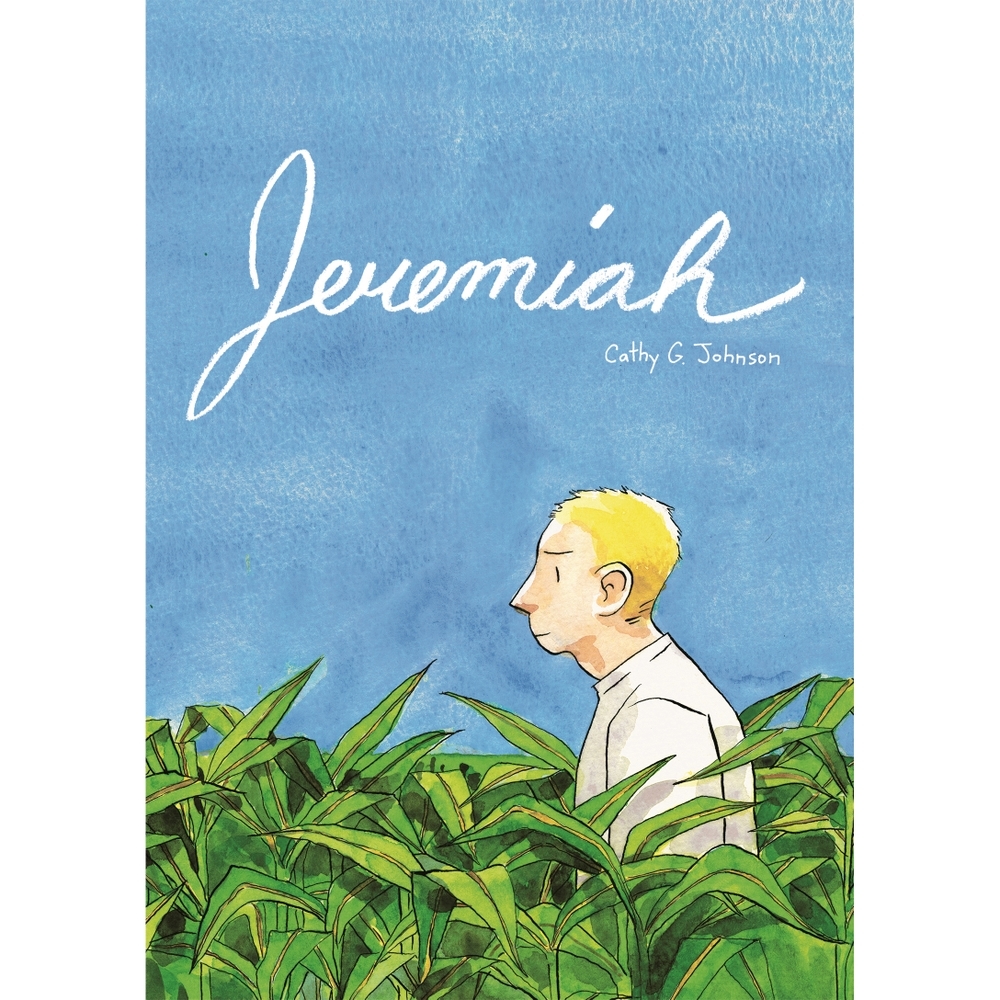

Other recent titles published by One Percent Press are Dakota McFadzean‘s Hollow In The Hollows, a story starring two children struggling with dark omens (I talked about it last year), and Present Tense by Buffalo-based illustrator and photographer Emily Churco, which collects mostly autobiographical one-page stories, alternating moments of reflection and impromptu gags. The next books are due for Small Press Expo in Bethesda on 19-20 September and are the collection of Jeremiah by Cathy G. Johnson (winner of an Ignatz at the latest SPX as Promising New Talent) and the twentieth issue of the series Simple Routines by JP Coovert, in addition to the reprint of The Aeronaut by Alexis Frederick-Frost.