Definire uno stile: One Percent Press

Ci sono, e ancor più c’erano, etichette discografiche che definivano uno stile, accompagnando contenuti musicali classificabili in un genere specifico con una precisa estetica delle copertine e degli LP: un paio di esempi a me cari sono la Factory e la Sarah Records, ma se ne potrebbero citare tanti altri. Nel campo del fumetto, questo fenomeno non può certo esistere secondo gli stessi canoni, perché se nella musica è già difficile demarcare le linee tra un genere e l’altro, figuriamoci in una forma d’arte così articolata e complessa come la nostra. La distinzione classica che viene fatta nel fumetto statunitense è molto più generica e riguarda la suddivisione tra prodotti mainstream, legati economicamente al mondo delle corporation ed esteticamente a contenuti apprezzati dal grande pubblico, e quelli “indie”, che invece nascono fuori dalla produzione di massa. Va da sè che il mondo indie dovrebbe anche veicolare contenuti alternativi a quelli mainstream, cosa che ormai non è più vera perché etichette indipendenti come l’Image sono dei colossi che producono sì materiale diverso dai fumetti di supereroi della Marvel o della Dc, ma tutt’altro che rivoluzionario o anticonvenzionale. Ecco dunque che “indie” e “alternative” non sono più sinonimi, tanto che per cercare prodotti fuori dagli schemi bisogna per forza esplorare l’underground, intenso non più come genere nato negli anni ’60 e caratterizzato dalla satira dello status quo, dalla presenza di sesso, droghe e oscenità varie, ma letteralmente come un sottobosco di micro-produzioni che nella realtà nord-americana è sempre più florido e interessante.

Tra le tante piccole case editrici di cui ho parlato su Just Indie Comics, ce n’è una, la One Percent Press, che non solo pubblica fumetti senza preoccuparsi dell’eventuale riuscita commerciale, ma che ha anche il merito di fare le proprie cose secondo il modus operandi di un’etichetta discografica di altri tempi. E non a caso oltre a pubblicare e distribuire fumetti il marchio fondato nel 2004 da Stephen Floyd e JP Coovert pubblica e distribuisce anche LP e CD di band come Wooden Waves e Tin Armor, in uno spirito che prende pieno spunto dalla filosofia Do It Yourself. E questo con una certa continuità, dato che in questi dieci e passa anni i due hanno fatto uscire oltre 50 fumetti e 25 dischi.

A definire il sound dei fumetti made in One Percent Press non è né la confezione, diversa a seconda dei casi, né la linea pulita dei disegni, che eppure costituisce una costante. Il punto di contatto tra un’uscita e l’altra riguarda piuttosto la tematica, dato che la gran parte degli albi si propone come una rilettura del genere “romanzo di formazione”, esplorando le inquietudini di bambini e adolescenti oppure mostrandoci dei venti-trentenni che cercano ancora la loro strada nel mondo. In questo senso l’albo migliore per capire l’idea dietro a questo progetto editoriale è Salad Days di JP Coovert. Brandon arriva a Minneapolis per incontrare un vecchio amico e passare un weekend di “movies, videogames, and pizza”. Uno è costretto a indossare la cravatta per il lavoro di designer in una corporation, l’altro ancora non sa bene che tipo di carriera intraprendere, ma entrambi hanno ormai famiglia e non riescono più a dedicarsi alle loro passioni. Il ricordo dei tempi passati li spinge a uscire dalla solita routine, a fare qualcosa di diverso, tanto che si ritrovano inseguiti da una macchina della polizia.

Non so quanto di autobiografico ci sia dietro le linee spigolose e il tratto essenziale di Coovert, ma uno dei due personaggi potrebbe essere proprio l’autore, ansioso di rimanere fedele ai sogni dell’adolescenza, di coltivare le proprie passioni e di non diventare una persona come tante. D’altronde la storia della One Percent Press è più o meno questa, cioè quella di due ragazzi che si sono conosciuti a vent’anni e che vivendo sempre in città diverse (la sede dell’etichetta è attualmente tra Minneapolis e Buffalo) hanno creato questa micro-realtà per rimanere in contatto e fare qualcosa insieme. Per quanto riguarda il nome, One Percent Press si riferisce al fatto che soltanto l’1% della vita è veramente eccezionale, soltanto l’1% del cibo è buonissimo e solo l’1% dei fumetti e della musica è realmente degno di nota: un concetto che per ammissione dello stesso Stephen Floyd è da ventenni, da giovani che cercano la propria affermazione non tanto nel mondo, ma contro il mondo.

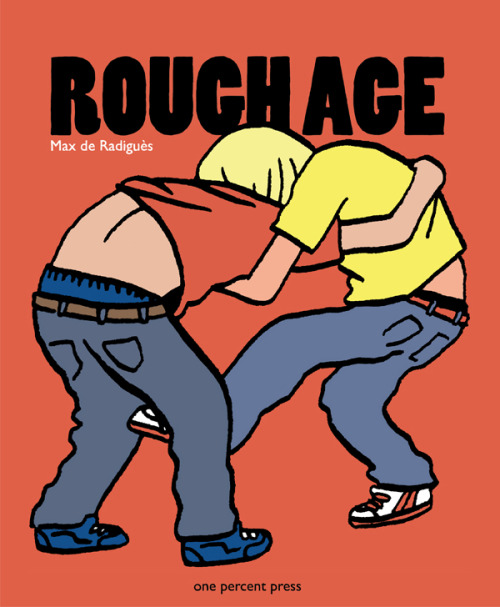

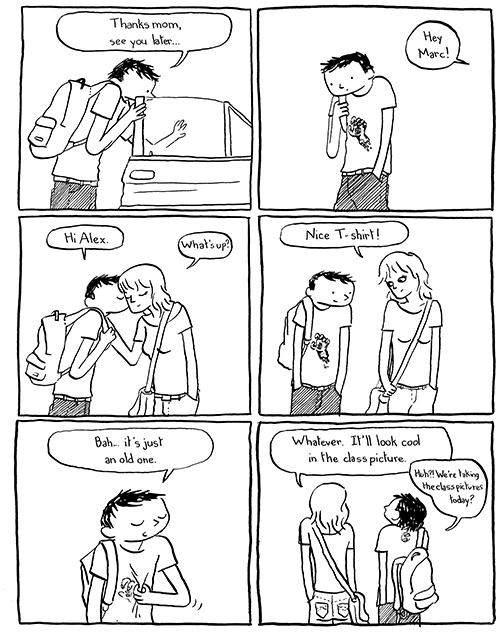

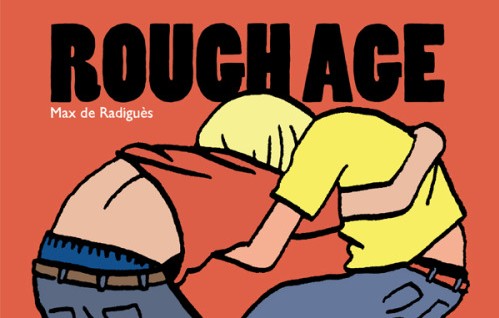

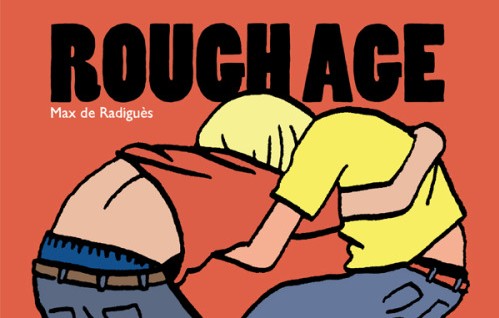

L’opera più rilevante uscita finora è la versione inglese de L’Âge Dur di Max de Radiguès, tradotta con il titolo Rough Age che purtroppo perde il bel gioco di parole dell’originale. Il contenuto però non cambia e così anche i lettori americani hanno potuto godersi in questo volumetto datato 2014 il materiale pubblicato dal cartoonist belga tra il 2009 e il 2010. Lo stile è apparentemente pulito ma sotto sotto nervoso, mostra delle deviazioni dai contorni rassicuranti della ligne claire, come se i tremolii del pennino riflettessero le inquietudini dei protagonisti, ragazzi in età scolastica che pensano soprattutto ai rapporti con l’altro sesso e che litigano, fanno a botte, copiano i compiti, sparlano gli uni degli altri. Una serie di storie si intrecciano tra loro con un susseguirsi continuo di personaggi, come Roman, che è preso di mira da un compagno e inventa una fidanzata immaginaria, oppure Gary, che sta con Louise ma è segretamente innamorato di Marc, o anche Ron, che viene lasciato dalla ragazza ma mostra un’aria da duro pur soffrendo in segreto. Con leggerezza ci si avvicina al finale, quando i ragazzi arrivano a posare per la fotografia di classe con i nasi rotti, i musi imbronciati, gli occhi neri dopo tutto quello che è successo nelle pagine del volume. Rough Age è per molti versi un classico fumetto franco-belga ma per l’aspetto minimalista si avvicina alle produzioni “indie” statunitensi: alla fine ne viene fuori una storia universale, che potrebbe raccontare le vicende dei bambini della gran parte del mondo occidentale.

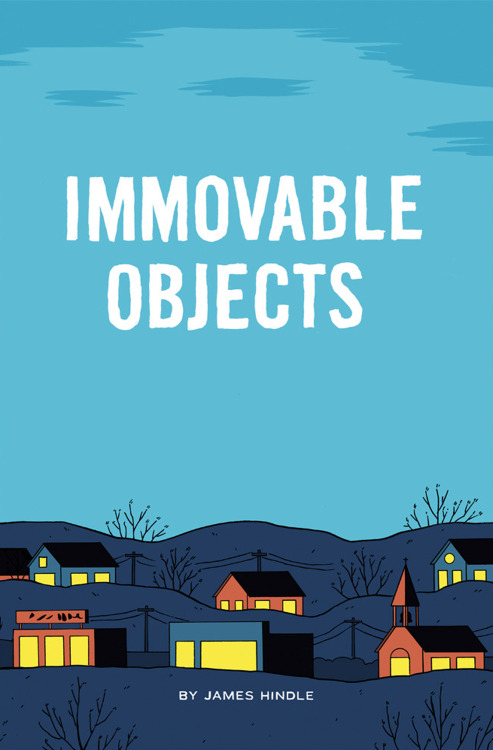

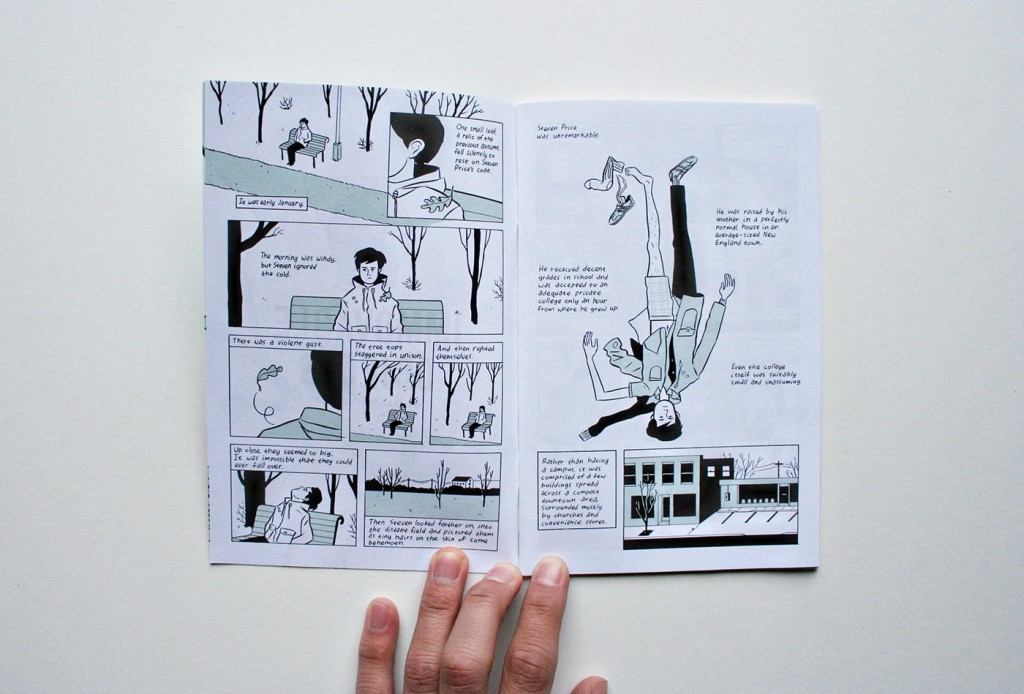

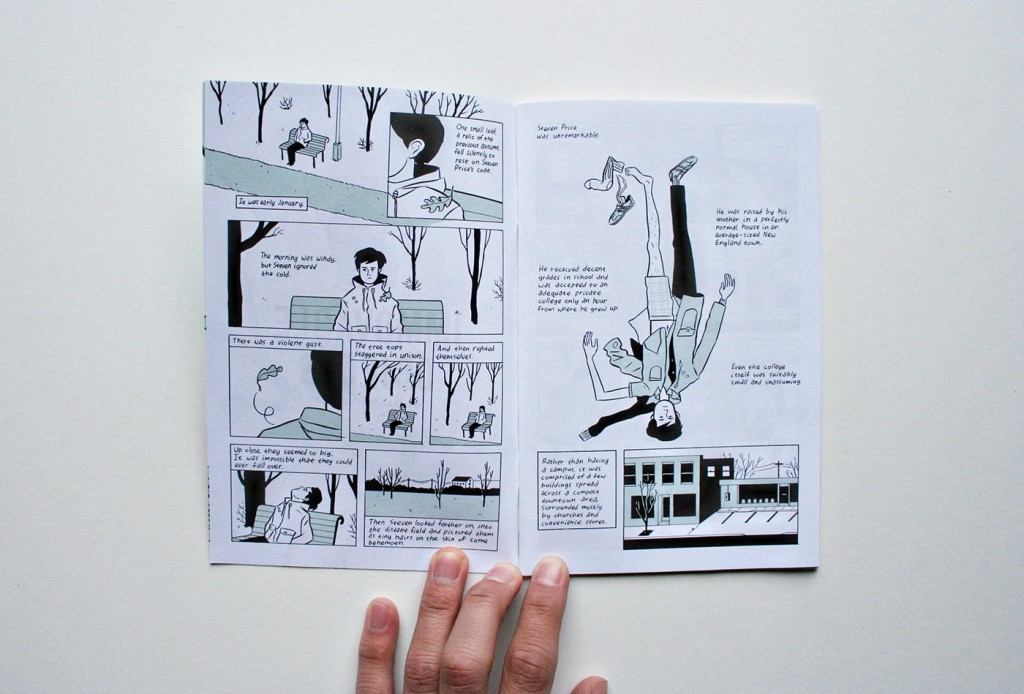

L’albo della One Percent Press che più rappresenta il genere “romanzo di formazione” è però Immovable Objects di James Hindle, autore che finora conoscevo per la breve Yellow Plastic pubblicata sul quarto numero dell’antologia Irene (qui la mia recensione). E i punti in comune tra le due storie non mancano, dato che entrambe fanno ampio uso di didascalie a mò di voce fuori campo per raccontare un rapporto tra un ragazzo impacciato e una ragazza ben più sveglia di lui, sicura nei modi di fare ma comunque tormentata. Qui in particolare seguiamo le ordinarie avventure di Steven Price, un tipo “anonimo”, “cresciuto dalla madre in una casa perfettamente normale in una città di medie dimensioni nel New England”. Steven “ha ricevuto voti decenti a scuola ed è stato ammesso in un accettabile college privato soltanto a un’ora da dove è cresciuto”, un college che era “adeguatamente piccolo e senza pretese”. Isolato dai compagni di scuola, solitario e meditabondo nonché con il pensiero ricorrente rivolto a un padre che non ha mai conosciuto, Steven è inizialmente raffigurato seduto sulla panchina di un parco, da solo, mentre le foglie degli alberi gli si poggiano sulla spalla. Le cose cambiano quando incontra Caroline, una compagna di scuola con cui costruisce un rapporto confidenziale ma privo di ogni risvolto sessuale. Come succede spesso in questi casi, l’amicizia si sfalda quando entra in gioco una terza persona, un professore di disegno da cui Caroline è sempre più attratta. Le battute e i cenni di intesa lasciano spazio a gelosie e desideri repressi, così che Steven è costretto a superare il facile appiglio della relazione con la ragazza per guardare dentro se stesso, acquisire sicurezza e forse maturare.

Anche Hindle come i già citati Coovert e de Radiguès ha un tratto semplice e pulito, anche se più rotondo rispetto a quello dei colleghi. Al di là del disegno in se stesso, ciò che colpiscono in Immovable Objects sono le soluzioni grafiche, spesso ottenute con la contrapposizione del bianco, del nero e del verde chiaro. La madre di Steven è raffigurata attraverso una sagoma bianca con contorni neri, ma non è definita come i protagonisti, rimane un personaggio sullo sfondo. Anche la figura del padre è indefinita, ma questa volta è nera, ancora più misteriosa. E quando la vicenda arriva alla sua conclusione anche la figura di Steven è diventata indefinita, del verde chiaro che costituisce l’altro colore dell’albo. Il cerchio si è chiuso e anche il protagonista non è più nulla per noi. Eppure Hindle è riuscito a farcelo diventare familiare in 36 pagine, regalandoci una storia profonda e piena di sfumature.

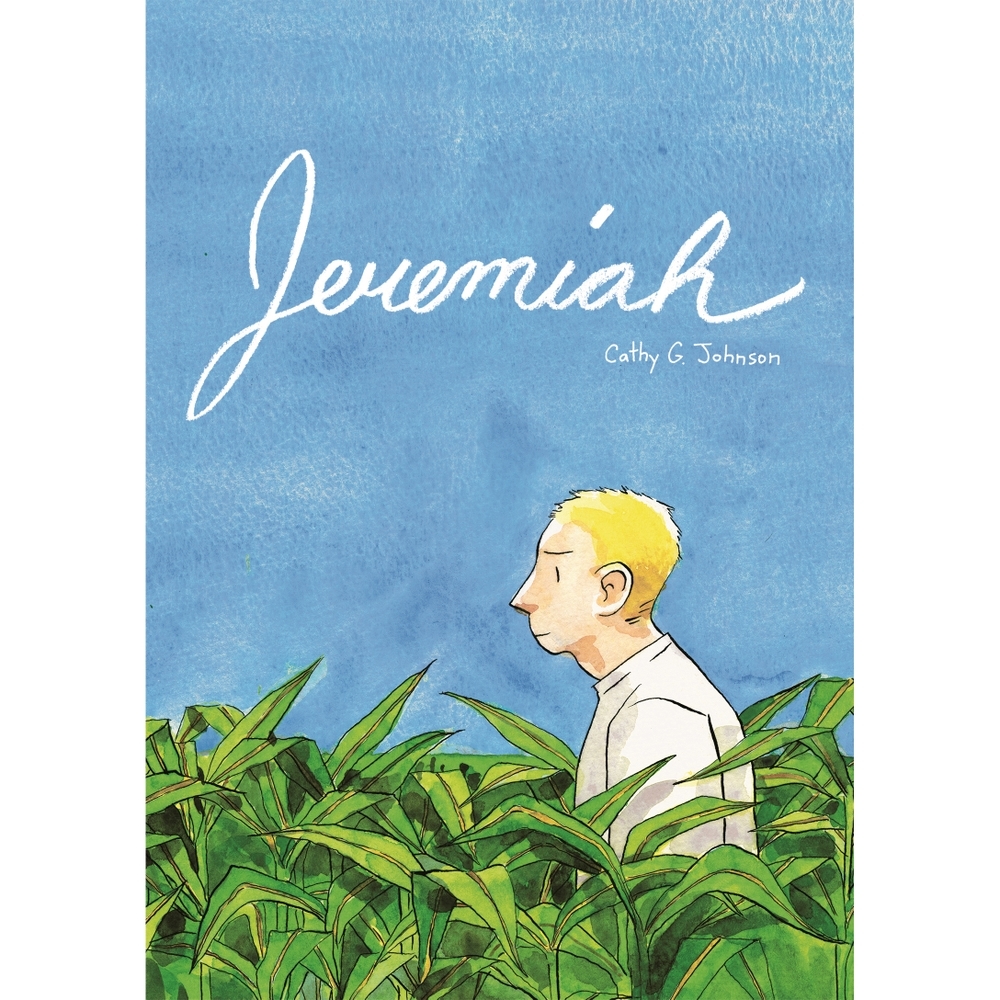

Altri titoli recenti pubblicati dalla One Percent Press sono Hollow In The Hollows del canadese Dakota McFadzean, un racconto che vede protagonisti due bambini alle prese con oscuri presagi (ne avevo parlato l’anno scorso), e Present Tense dell’illustratrice e fotografa di Buffalo Emily Churco, che raccoglie storie di una pagina autobiografiche, tra momenti di riflessione e gag estemporanee. Le prossime novità sono attese per la Small Press Expo di Bethesda del 19-20 settembre, quando debutteranno la raccolta del Jeremiah di Cathy G. Johnson (tra l’altro vincitrice dell’Ignatz come miglior talento emergente proprio all’ultima SPX) e il ventesimo numero della serie Simple Routines di JP Coovert, oltre alla ristampa dell’esaurito The Aeronaut di Alexis Frederick-Frost, autore visto in Italia con il libro Avventure tra le nuvolette pubblicato da Proglo.

Defining a style: One Percent Press

There have always been record labels that defined a style, combining a specific genre with very distinctive aesthetics: Factory and Sarah Records are a couple of examples, though I could offer a lot more. In comics, this phenomenon can’t exist in the same way; if it’s difficult to demarcate boundaries between one genre and another in music, it is almost impossible to do so in an art form as articulate and complex as comics. The usual distinction made in the US market distinguishes between general or mainstream comics and “indie” comics, with mainstream comics linked economically to large corporations and aesthetically to contents appreciated by the mass public, and indie products made outside mass production. It goes without saying that the indie world should also convey different contents from those of Marvel or DC, but this isn’t really the case, because independent labels like Image are giants that publish a lot of comics that are far from revolutionary or unconventional. In comics, “indie” and “alternative” are no longer synonymous, and to find things that are truly different we have to explore the underground, that is no longer a genre born in the 60s and characterized by the satire of the status quo and by the presence of sex, drugs and various obscenities, but an “underworld” of small publishers that is more and more fruitful and interesting in the North American scene.

One of these small publishers is One Percent Press, a label that not only publishes comics without worrying about eventual commercial success, but that also does its own thing according to the modus operandi of a record label of the past. So it isn’t a coincidence if the brand founded in 2004 by Stephen Floyd and JP Coovert publishes and distributes not only comics but also LPs and CDs of bands such as Wooden Waves and Tin Armor, in a spirit that takes its cue from the Do It Yourself philosophy. And they do it with a reasonable continuity, since the two have released over 50 comics and 25 albums in the past ten-odd years.

To define the “sound” of One Percent Press comics is neither the package, which differs from comic to comic, nor the clean lines of the drawings, even if this is a recurring feature. The point of contact is rather the subject matter, since most of the books are a reinterpretation of the coming-of-age genre, exploring the concerns of children and adolescents or showing people in their twenties and thirties who still are looking for their place in the world. In this sense, the book to better understand the idea behind this editorial project is Salad Days by JP Coovert. Brandon comes to Minneapolis to meet an old friend and spend a weekend of “movies, videogames, and pizza”. One is forced to wear a tie for his work as a designer in a corporation, the other still doesn’t know what kind of career he would like to choose. Both have family and have to face the consequences of growing up, included the fact they now have little time to devote themselves to their passions. The memory of past times drives them to get out of the usual routine, to do something different, so that they end up chased by a police car.

I don’t know how many autobiographical elements are behind the angular lines and the essential drawings of Coovert, but one of the two characters could be the author himself, wishful to stay true to the dreams of his youth. Moreover, the history of One Percent Press is more or less this: that of two guys who met in their twenties and have created this micro-reality to keep in touch and do something together, even though they’ve always lived in different cities (the label is currently located between Buffalo and Minneapolis). As for the name, One Percent Press refers to the fact that only 1% of life is truly excellent, only 1% of food is very good and only 1% of comics and music is really noteworthy: a concept that, according to the same Stephen Floyd, is typical of twenty-somethings, of young people seeking their way not so much in the world, but against the world.

The most important release to date is the English version of L’Âge Dur by Max de Radiguès, translated under the title of Rough Age, which unfortunately loses the wordplay of the original. But the content doesn’t change and so the American readers can enjoy in this 128-page book from 2014 the original zines self-published by the Belgian cartoonist between 2009 and 2010. The style is clean on the surface but nervous underneath, and it shows deviations from the reassuring forms of ligne claire, as if the shakes of the pen reflect the concerns of the characters, schoolchildren who think above all of relationships with the opposite sex while they argue, fight, copy homework and gossip about each other. The different plots intertwine, and a lot of characters stand out: Roman is mocked by a classmate and invents an imaginary girlfriend, Gary has an affair with Louise but is secretly in love with Marc, Ron breaks up with his girlfriend and shows indifference while suffering in secret. Lightly we reach the conclusion, when the boys have to pose for a class picture with broken noses, sullen faces and black eyes after all that has happened in the pages of the book. Rough Age is in many ways a classic French-Belgian bande-dessinée, but the minimalist approach recalls American indie comics. In the end it comes out a universal story that could tell the life of children from much of the Western world.

The One Percent Press book fitting perfectly in the coming-of-age genre is Immovable Objects by James Hindle, an author whom I already knew for the brief Yellow Plastic published in the fourth issue of Irene anthology (my review is here). The two stories have different points in common, since both make extensive use of voiceover in the captions to tell a relationship between a very awkward boy and a troubled girl smarter than him. Here in particular we follow the ordinary adventures of Steven Price, an “unremarkable” boy, “raised by his mother in a perfectly normal house in an average-sized New England town”. Steven “received decent grades in school and was accepted to an adequate private college only an hour from where he grew up”, a college that was “suitably small and unassuming”. Isolated from school friends, lonely, contemplative and with the recurring thought of a father he never knew, Steven is initially depicted sitting alone on a park bench, while tree leaves fall on his shoulder. Things change when he meets Caroline and builds with her a confidential but lacking of any sexual implication relationship. As often happens in these situations, the friendship falls apart when a third person comes into play, in this case a professor of drawing to whom Caroline is increasingly attracted. Jokes and winks give way to jealousy and repressed desires, so that Steven is forced to overcome the easy support of the relationship with the girl to look inside himself, become more confident and perhaps mature.

Like the aforementioned Coovert and de Radiguès, Hindle has a simple and clean line, although more round than that of his colleagues. Immovable Objects presents a lot of interesting graphic solutions, often obtained with the juxtaposition of black, white and light green. Steven’s mother is depicted by a white shape with black outlines: she is a background character, so she isn’t defined as the protagonists. Even the father figure is undefined, but this time is completely black, even more mysterious. And when the story reaches its conclusion the figure of Steven becomes blurry too, made of light green. The circle is closed and also the main character can become a vague shape. Yet Hindle managed to make him familiar to us in these 36 pages, providing a deep and nuanced story.

Other recent titles published by One Percent Press are Dakota McFadzean‘s Hollow In The Hollows, a story starring two children struggling with dark omens (I talked about it last year), and Present Tense by Buffalo-based illustrator and photographer Emily Churco, which collects mostly autobiographical one-page stories, alternating moments of reflection and impromptu gags. The next books are due for Small Press Expo in Bethesda on 19-20 September and are the collection of Jeremiah by Cathy G. Johnson (winner of an Ignatz at the latest SPX as Promising New Talent) and the twentieth issue of the series Simple Routines by JP Coovert, in addition to the reprint of The Aeronaut by Alexis Frederick-Frost.

“mini kuš!” #34-37

Four mini kuš! are due next 22th August along with the 22th issue of š! anthology, this time dedicated to fashion. Waiting to see how the various cartoonists have exalted, mocked, reinvented the world of fashion, now I’ll take a look at the new mini-comics, 28 color pages each, stapled in A6 size and printed on a beautiful thick and opaque paper.

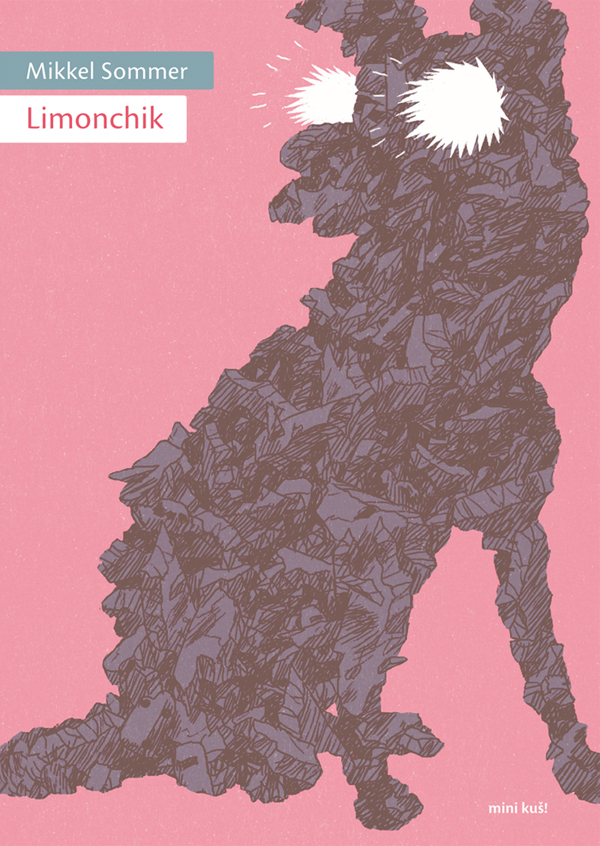

The 33th mini kuš! is by Mikkel Sommer, a Danish artist born in ’87 who has already published in France with Casterman and in England for Nobrow. Limonchik is an almost wordless story (only 2 of the 24 pages have a bit of text) about the return to our planet of Laika, the dog “lost in space” (Limonchik was one of the nicknames Soviets gave her). The cover with lightnings bursting out of the eyes of the dog is a prelude to the second part of the mini-comic, full of storms and destructions, in an apocalyptic scenario alternating pages on pink background with others where a deep dark blue prevails, in a juxtaposition of day and night, Earth and space. Mankind is totally absent here, there are only a dog and an asleep and then devastated civilization.

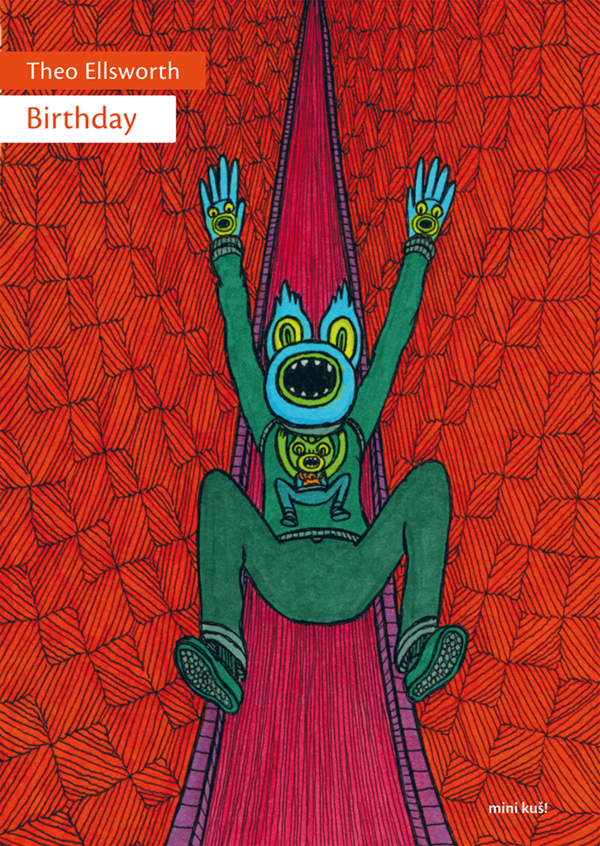

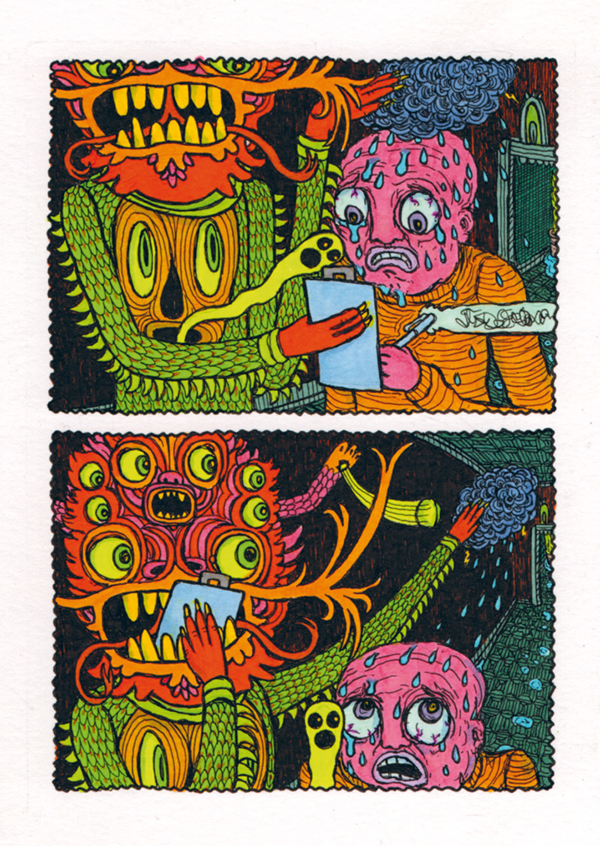

If Sommer’s idea is effective but at the same time rather simple, American cartoonist Theo Ellsworth, best know for his series Capacity and for the two books of The Understanding Monster, deals in Birthday with more complex and even psychedelic topics. Probably because when I discovered the world of underground comics his illustrations were almost everywhere, but in these visionary games about rituals of physical and mental rebirth I see always the echo of Italian artist Matteo Guarnaccia, even if I don’t know if Ellsworth has ever heard of him. Jim Woodring could be an influence too, however putting comparisons aside this totally silent story is funny, disturbing and at the end liberating.

I think it’s easy reading Ellsworth’s comics admiring his dreamlike and fantastic worlds, but he is also a master in illustrating human faces, as we can see from the desperate expression of the main character in the first page, from his dread when he agrees to subject himself to the initiation ceremony on page 4, from his disbelief when he realizes what is happening in the final sequence.

Another wordless mini-comic is Pages to Pages by Hong Kong artist Lai Tat Tat Wing, an habitué in Latvian anthologies who gets now a mini kuš! all for him. Protagonists of this short tale are two faceless men who laugh together, start arguing and then chase each other, in a crescendo of cartoon-like situations filled with surrealist elements. I’ll seem a fool but I saw the echo of Grant Morrison’s Doom Patrol, for example in the books that open their pages like possessed or in the hands coming from the sky. Even the metanarrative theme can remember Doom Patrol, but here this topic is mixed with that of conflict between traditional books and technology. Both culminate in the whimsical and in some way disturbing final scene, where faceless men use their technological devices all together. The colors are a little bit feeble in this book – I would have preferred brighter tones – but probably it’s only a matter of taste.

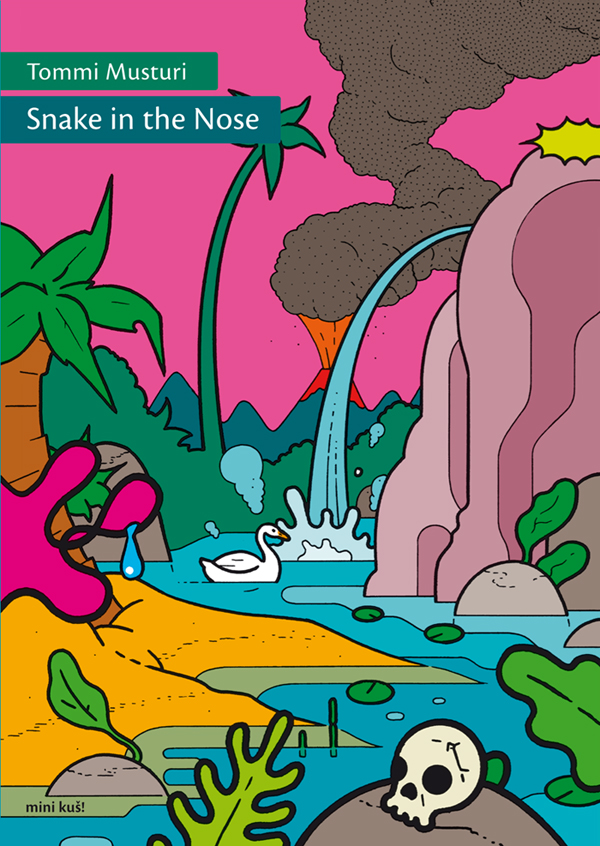

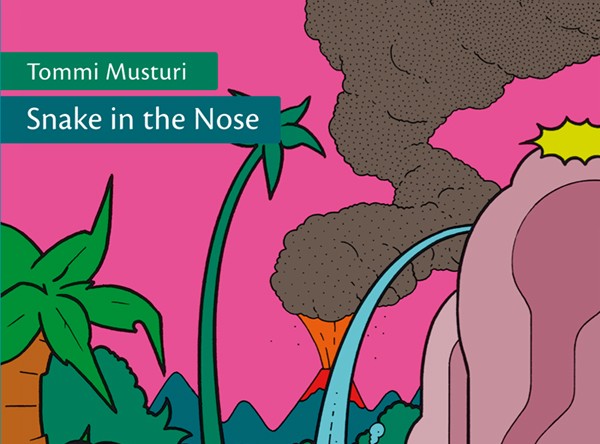

Who certainly didn’t skimp on bright colors is the veteran of European underground comics Tommi Musturi, for whom 2015 is a particularly important year, since Fantagraphics will release the collection of his The Book of Hope in November. The mini opens with a blonde lady drinking a cocktail and smoking, until something falls on her head… I won’t say what it is, but I assure you this is a scene that represents at full the hatred of the protagonist towards the whole world, worthy of a character of an Ivan Brunetti’s comic. But in the end the man isn’t so terrible as he seems if he dreams rainbows and unicorns and if we catch him dancing naked on Like a Virgin… Beyond the funny plot, the Finnish cartoonist is at his best in some brilliant pages that combine inventiveness and storytelling: see for example the one in which Musturi describes a series of possible suicides or the whole colorful dream sequence. Along with that of Ellsworth, Snake in the Nose is the most successful mini kuš! of this summer batch.

You can pre-order right now these four mini kuš! here at $6 each (worldwide shipping included in price).

You can pre-order right now these four mini kuš! here at $6 each (worldwide shipping included in price).

“mini kuš!” #34-37

Nuova serie di mini kuš!, tutti in uscita il 22 agosto insieme al 22esimo numero della più massiccia antologia, che questa volta ha scelto il “fashion” come tema. In attesa di vedere come i vari cartoonist hanno esaltato, deriso, reinventato il mondo della moda, vediamo adesso cosa ci riservano questi nuovi quattro albetti, tutti di 28 pagine a colori, spillati in formato A6 e stampati su una bella carta spessa e opaca.

Il 33esimo mini kuš! è appannaggio di Mikkel Sommer, artista danese classe ’87 che si è già fatto notare pubblicando in Francia per Casterman e in Inghilterra per Nobrow. Al debutto assoluto per l’editore lettone, Sommer tira fuori in Limonchik una storia quasi del tutto muta (ci sono solo 2 pagine su 24 con un accenno di testo) che immagina il ritorno sulla terra della cagnetta “lost in space” Laika, altrimenti nota proprio come Limonchik. I fulmini che escono dagli occhi dell’animale, già mostrati in copertina, preludono a una seconda parte dell’albetto piena di tempeste e distruzioni, in uno scenario apocalittico che alterna tavole su sfondo rosa ad altre blu scuro, in una giustapposizione tra giorno e notte, terra e spazio profondo. L’uomo è qui totalmente assente, ci sono solo un cane e una civiltà prima addormentata, poi devastata.

Se l’idea di Sommer è efficace ma al tempo stesso piuttosto semplice, lo statunitense Theo Ellsworth viaggia su coordinate più complesse e persino psichedeliche. Sarà che quando ho scoperto il mondo dei comics e dell’arte underground le sue cose erano un po’ dappertutto, ma io in questi giochi visionari che rimandano a riti di rinascita mentale e corporea rivedo sempre l’eco del nostro Matteo Guarnaccia, in questo caso mixato con l’altro americano Jim Woodring. Paragoni a parte, Ellsworth crea in queste pagine una storia totalmente muta ma che riesce al tempo stesso a essere divertente, inquietante e alla fine liberatoria.

Ma non fatevi incantare soltanto dalle atmosfere oniriche e dalle linee intrecciate di questo Birthday, perché l’autore di Capacity e di The Understanding Monster è un maestro anche nel disegnare volti umani ed espressioni, come la faccia disperata del protagonista nella prima pagina, il suo timore mentre accetta di sottoporsi al rito iniziatico a pag.4, l’incredulità quando capisce cosa gli sta succedendo nella sequenza finale.

Dato che non c’è due senza tre, anche Lai Tat Tat Wing non fa uso di parole nel suo mini-albo. L’artista di Hong Kong è presenza quasi fissa nelle antologie lettoni e non poteva mancare prima o poi un mini kuš! a lui interamente dedicato. Pages to Pages vede i due protagonisti senza volto ridere, litigare e poi infine inseguirsi, in un crescendo di situazioni degne di un cartone animato ma in cui non mancano elementi surrealisti. Sembro scemo se dico di vedere qua e là l’eco della Doom Patrol di Grant Morrison? Beh, forse sì, ma i libri che si aprono impazziti e le mani che piovono dal cielo possono suggerire questa improbabile analogia. Presente anche il tema metanarrativo del conflitto fra pagina disegnata e tecnologia, che trova degno compimento nella scena finale. A mio parere visto il tono della storia dei colori più incisivi non avrebbero guastato, ma probabilmente è solo una questione di gusti.

Chi sicuramente non ha fatto economia di colori sgargianti è il veterano del fumetto underground europeo Tommi Musturi, per cui il 2015 è un anno particolarmente importante, dato che a novembre uscirà la raccolta del suo The Book of Hope per Fantagraphics. L’albo si apre con una bionda signora intenta a bere un cocktail e fumare, fino a che qualcosa non le cade in testa… Non vi dirò di che si tratta, ma vi assicuro che è una scena che ben rappresenta l’astio del protagonista nei confronti del mondo intero, degno di un personaggio di Ivan Brunetti. Ma alla fine quest’uomo non è poi così terribile come sembra se sogna arcobaleni e unicorni e se si trova a ballare tutto nudo sulle note di Like a Virgin di Madonna… Al di là della trama, comunque divertente, il lavoro del cartoonist finlandese si esalta in alcune tavole geniali che uniscono inventiva e storytelling: si veda per esempio quella in cui inscena una serie di possibili suicidi per il suo protagonista o tutta la coloratissima sequenza onirica. Insieme a quello di Ellsworth, Snake in the Nose è il mini kuš! più riuscito di questa infornata estiva.

I quattro albetti sono già disponibili qui al prezzo di $6 l’uno incluse spese di spedizione.

I quattro albetti sono già disponibili qui al prezzo di $6 l’uno incluse spese di spedizione.