A Cake 2015 photo gallery

As some of you already know, around here I’m talking mostly about comics (indie, underground, alternative or whatever) from North America and so I find a festival as the Chicago Alternative Comics Expo (CAKE for friends) very interesting, since it gathers a lot of cool cartoonists and publishers from United States and Canada. Even if I wasn’t there on June 6-7, I decided to dedicate a gallery at this event, assembling photos I saw on the various social networks. All the pictures are used with the permission of the authors and if I made any mistake or I’ve forgotten to mention someone, please contact me at justindiecomics [at] gmail [dot] com. Many thanks to everyone for the cooperation. Just click on any image to open the gallery.

- Entrance! (photo by Jared Smith)

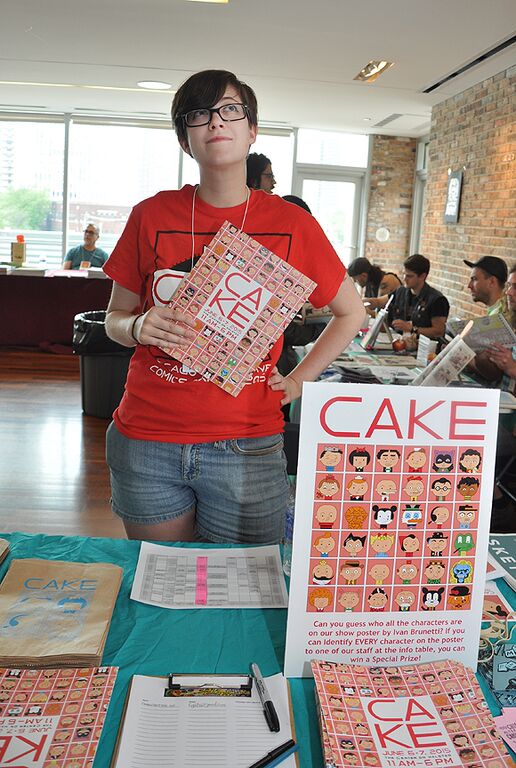

- Registration is open (photo by Chester Alamo-Costello)

- The fest just before the door opened (photo by J Derf Backderf)

- CAKE! (photo by Corinne Halbert)

- Retrofit Comics table (photo by Jared Smith)

- Sam Alden (photo by Jared Smith)

- Roman Muradov (photo by Jared Smith)

- Ed Luce’s table with many issues of “Wuvable Oaf”

- Another pic of Ed Luce’s table

- The Ladydrawers Comics Collective at CAKE (photo by Delia Jean)

- Jillian Tamaki signing (photo by Matt Brady)

- Sophie McMahan (photo by Polly Bland)

- Another pic of Sophie McMahan’s table

- Ed Kanerva at Koyama Press table (photo by Matt Brady)

- Nathan Ward (photo by Matt Brady)

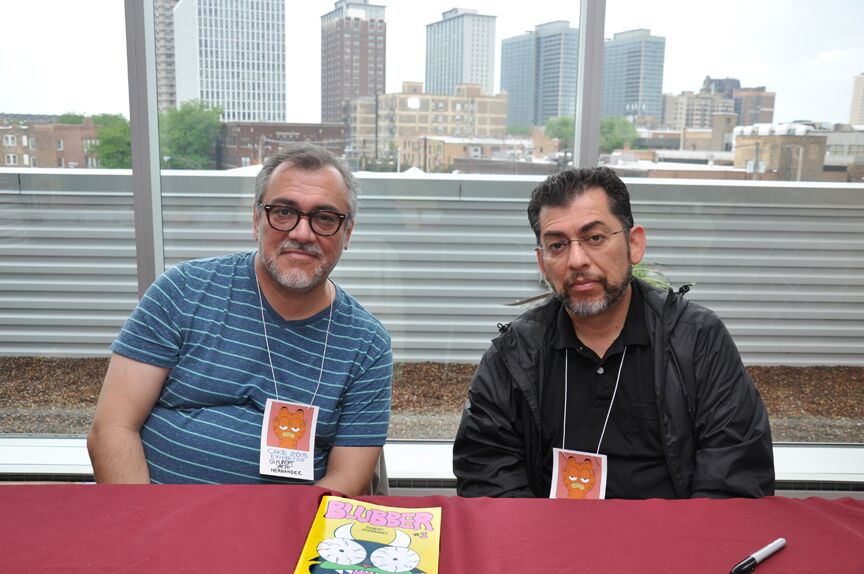

- Gilbert and Jaime Hernandez (photo by Chester Alamo-Costello)

- John Porcellino (photo by Matt Brady)

- CAKE by Chris Cilla

- Chris Cilla’s table

- Zak Sally (photo by Matt Brady)

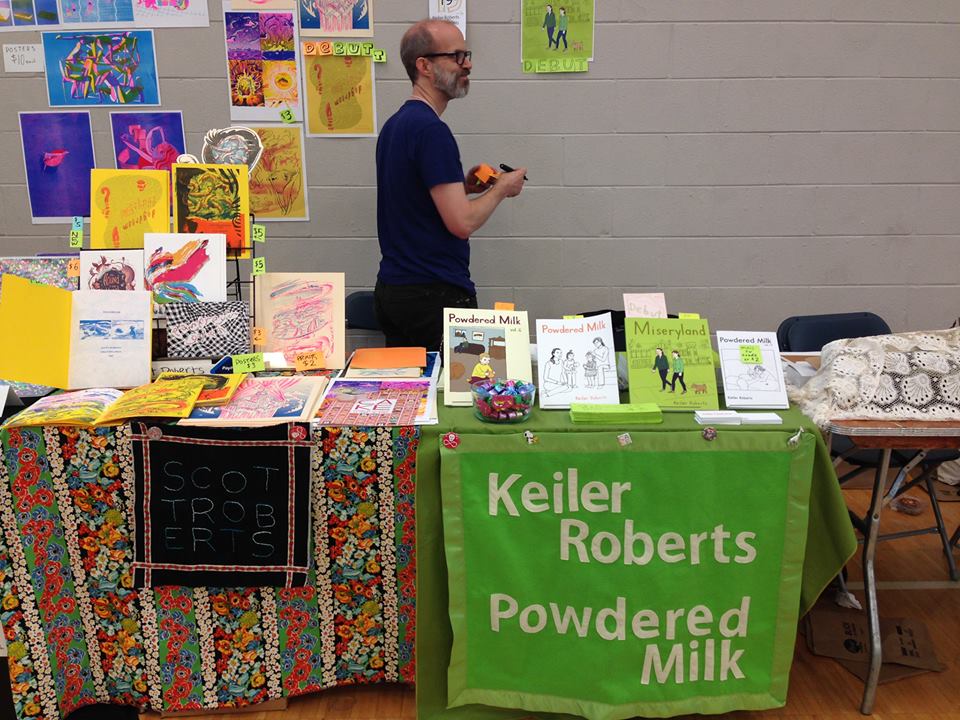

- Scott Roberts with Keiler Roberts, one of the special guests of the show

- Keiler Roberts’ table with the new “Miseryland”

- CAKE 2K15 (photo by Marco Giampaolo)

- Kelly Froh and Max Clotfelter (photo by Marco Giampaolo)

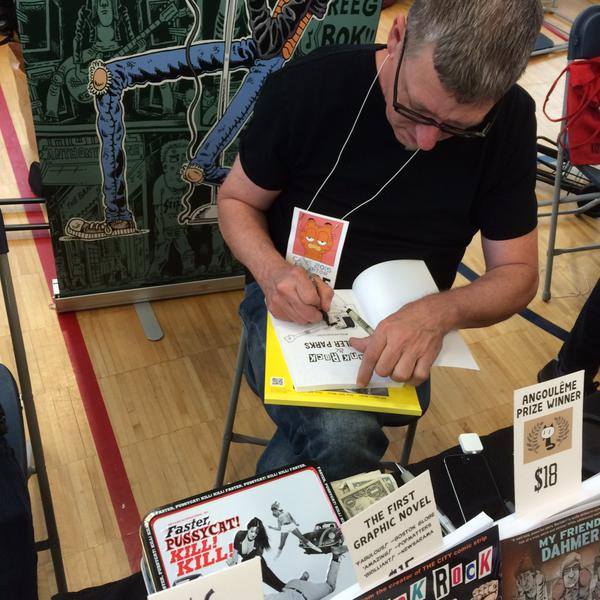

- J Derf Backderf signing (photo by Gene Kannenberg Jr)

- Gene Kannenberg Jr in a Joey Ramone shirt by J Derf Backderf

- Garfield at CAKE! (photo by Alex Nall)

- Darling Sleeper table (photo by Jesse Lucas)

- Ryan Standfest of Rotland Press with Paul Nudd

- Rotland Press table (photo by Ryan Standfest)

- Paul Nudd and Onsmith (photo by Chester Alamo-Costello)

- The Los Bros Hernandez panel (photo by Gene Kannenberg Jr.)

- Caitlin McGurk interviewed Los Bros Hernandez

- Gina Wynbrandt at the 2D Cloud table

- Corinne Halbert with her books “Hate Baby Four” and “Bad Touch” (with Scott R Miller)

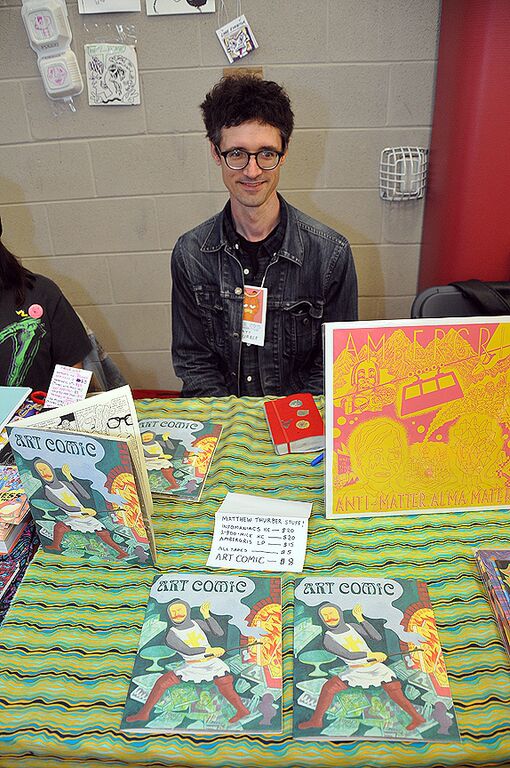

- Matthew Thurber (photo by Chester Alamo-Costello)

- Sophie Goldstein

- CAKE Kick-Off, Archer Ballroom, 6-5-15 (photo by Chester Alamo-Costello)

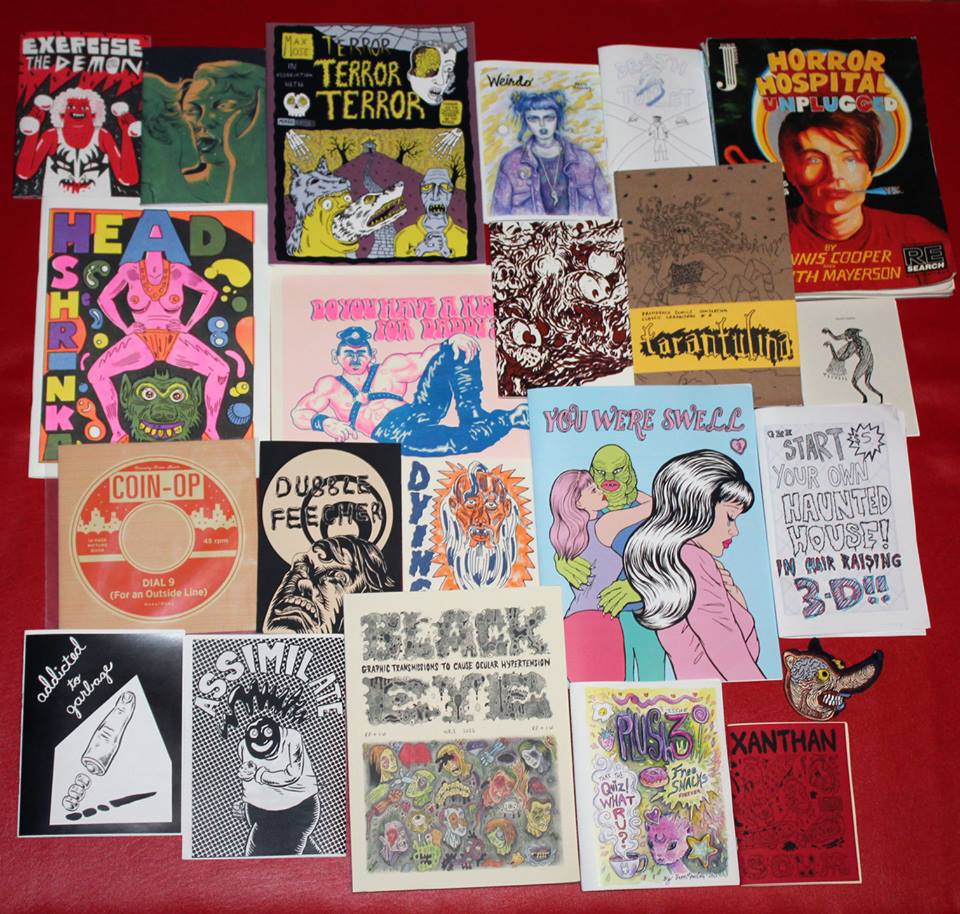

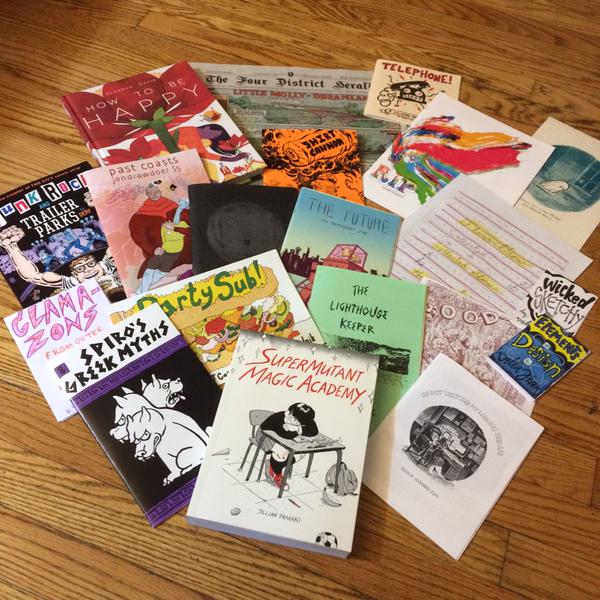

- CAKE haul by Cathy Hannah

- CAKE haul by Corinne Halbert

- CAKE Kick-Off, Archer Ballroom, 6-5-15 (photo by Chester Alamo-Costello)

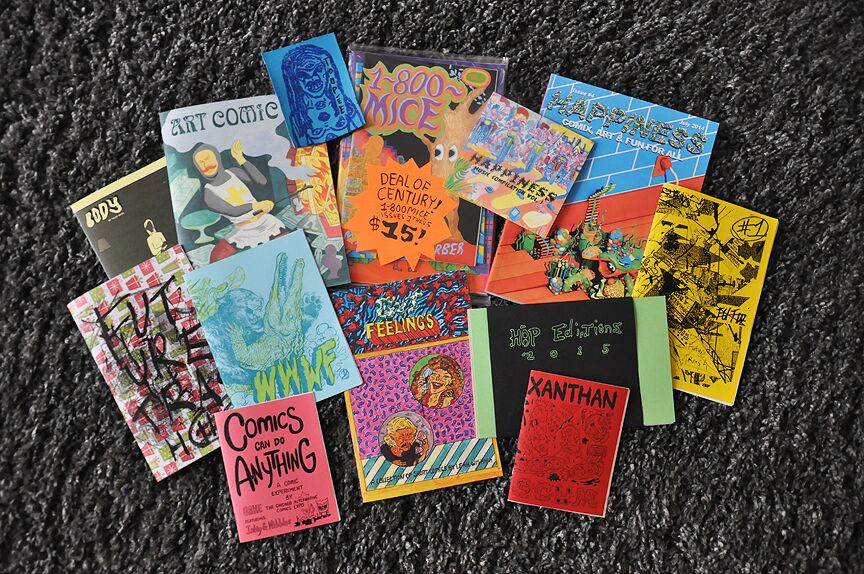

- CAKE haul by Chester Alamo-Costello

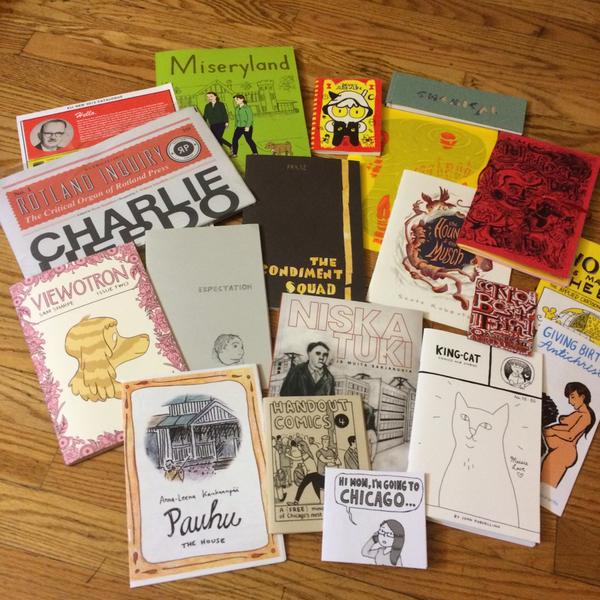

- Saturday’s haul by Gene Kannenberg Jr.

- 2015 CAKE Afterparty, 6/6/15 at The Observatory, with Ambergris featuring Matt Thurber, Traducer featuring Lane Milburn, Pet Theories featuring Brian Cremins, and Naff Whiff featuring Eddy Rivera (photo by Chester Alamo-Costello)

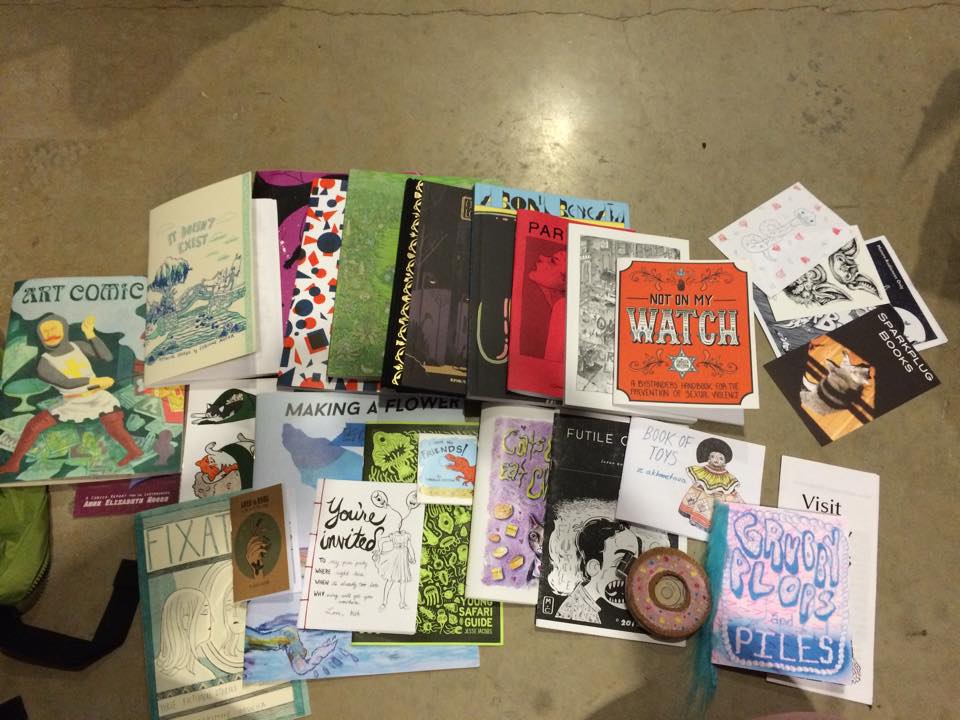

- CAKE haul by Allison Alleman

- Sunday’s haul by Gene Kannenberg Jr.

- Another pic of 2015 CAKE Afterparty, 6/6/15 at The Observatory (photo by Chester Alamo-Costello)

- Keiler and Scott Roberts’ haul

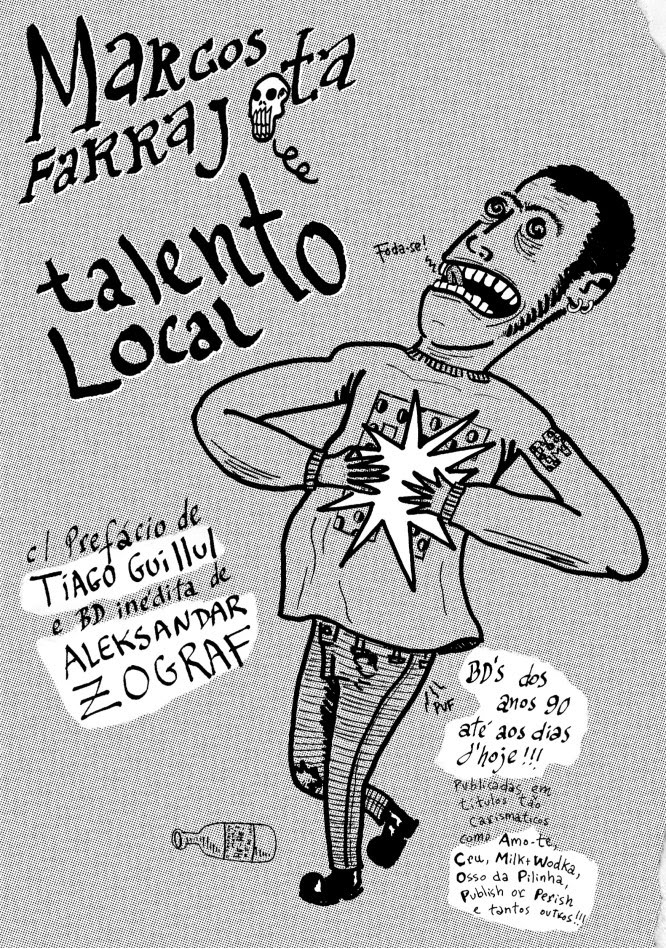

Marcos Farrajota and Portuguese comics

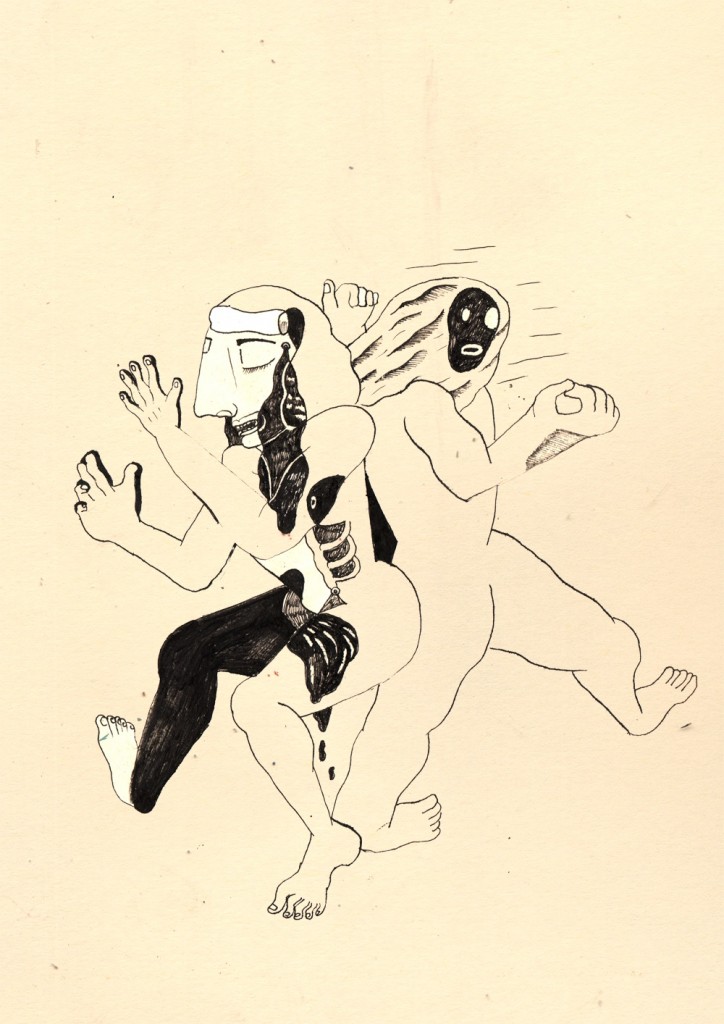

Marcos Farrajota is the editor of š! #20, the special issue of the Latvian anthology dedicated to Portuguese comics (you can read my review here), but he’s also the guy behind a lot of cool projects in Portugal, a librarian in Bedeteca de Lisboa – one of the best comics place in Europe – and a cartoonist, as you can see in his collection Talento Local. I’ve interviewed him to talk about comics in Portugal and some other stuff.

I’d like to start this interview sorting out all your various projects, from the fanzine Mesinha de Cabeceira, born in 1992, to Mmmnnnrrrg collective, which is celebrating 15 years right now, up to Chili Com Carne, perhaps the label best known outside Portugal and with a frequently updated blog. Can you tell me how you’ve evolved from project to project and how you’re giving your attention at the different labels/publications at the moment?

Well, everything is very organic, I mean, there isn’t an obligation to release every year one Mesinha de Cabeceira – like between 1997 and 2000 it took three years to release a new issue… Also, Mesinha is sometimes published by CCC, others by MNRG… A mess to librarians and collectors, I guess.

CCC has also more people involved so we can split work… And MNRG is me and Joana Pires – we are a couple, you see? So we manage at home our ideas.

All projects are “hobbies”, not professional works that put bread on the table… We relax when we have to relax and we act when we need to act!

Looking at your books and at the events you organize, the Portuguese scene seems quite lively. Yet the introduction to š! #20 emphasizes that making comics is a solitary process and describes the medium as “a form of torture, a useless effort devoid of causes or consequences that offers us neither glory nor any sort of personal reward”. It’s a similar concept to Pessoa’s “Everything we do, whether in art or in life, is a defective version of what were our initial ambitions”, as if you came at this idea of the futility of making comics during these years as an artist and as a publisher…

There’s been a darker time in the Portuguese scene but now there’s a new breed full of energy and ideas… It’s been exciting these last five years I guess, after a period of “nothing seems to be happen” from 2005 to 2010. So there are the “pros” working for USA, small publishers growing and keeping the light alive, medium publishers coming back and a growing attention on the graphic novel market. Let’s hope this helps to more experimental and cutting edge comics to develop even more… Because if not, it’s just a big black hole, creators feel hopeless since nobody will understand or care – even the people who state they like comics – those are actually the worst because they are conservative assholes that collect juvenile crap. I guess that’s why I always looked for people outside Portugal so that you may have more perspective and feedback. New generation like Amanda Baeza by instinct already knew that and her first book was published in Latvia, which is an awesome and interesting situation.

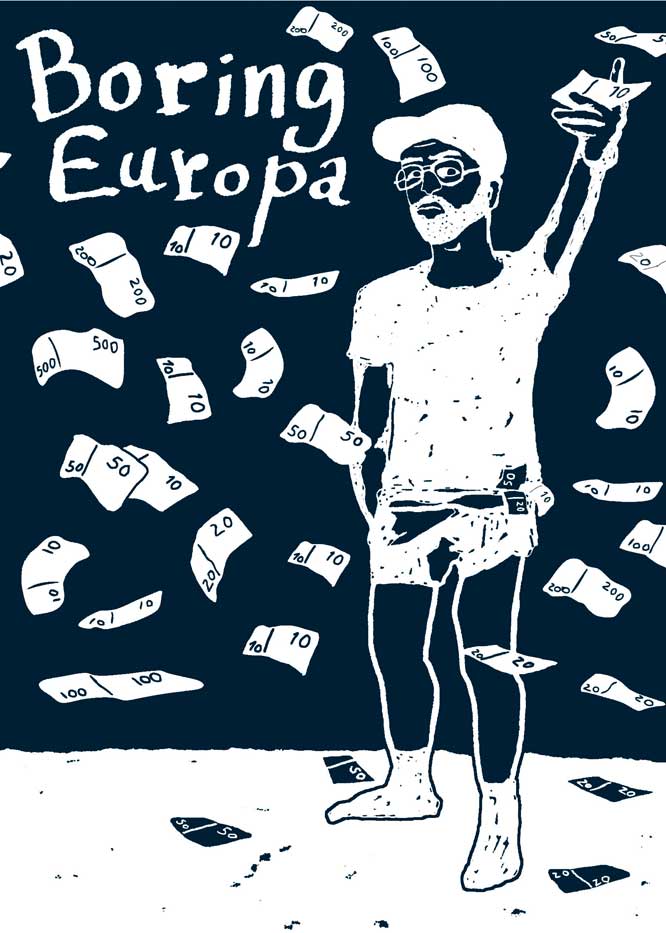

Anthologies as Mutate & Survive and Boring Europa, which connected Portuguese cartoonists with artists from all over Europe, date back to several years ago, and the last experience in this field, Futuro Primitivo, is from 2011. Recently Chili Com Carne is focusing more on books made by a single author. Is this a precise choice or only a coincidence? Do you think this is a current trend in the market, that now is harder to sell an anthology or a magazine than a so-called “graphic novel”?

Pure coincidence. It was by cosmic forces that graphic novels of David Campos, Francisco Sousa Lobo, André Coelho and Nunsky appeared… And it’s also true that to make anthologies in an interesting way (by the theme, for example) is some hard work for the editor! We still do anthologies like the QCDA series or the next volume of Zona de Desconforto (about foreign comics authors experiencing live in Portugal). New solo books will happen this year which is good just because in this way there are more different books to read and experience.

As for market, it’s obvious that solo graphic novels are THE market format to sell in the last 10 years but you can imagine that in literature world there are also anthologies and they sell less because they’re for a more restricted public like the people of the “scene”, not for a big audience. For our very small market (in Portugal) and printrun (of CCC or MNRG) actually there’s no big difference, most of our anthologies are sold out and solo books are still available – but then again, solo graphic novels are like only three years old…

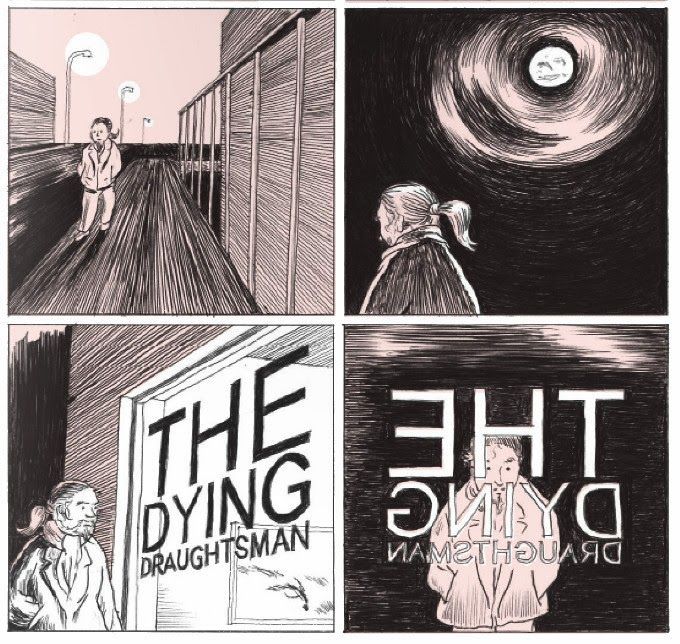

Some of your latest books are different from your past publications, since they don’t have the typical underground contents or aesthetics of the past, in the sense that they aren’t provocative or “dirty”. For example Francisco Sousa Lobo’s The Dying Draughtsman is an intimate and deep story, while Askar, O General by Colombian artist Dileydi Florez is a very well-finished graphic work looking at the representation of the great historical battles of the past that we find in painting more than in comics.

We are getting old!!!

No way man… Come on, Papá em África by Anton Kannemeyer is full of black dicks, Erzsébet is full of virgin blood, Rudolfo is puking a lot in Malmö Kebab Party and if I’ll publish a new book this year there will be loads of my bad drawings (and dicks!)… You’ve just got to see some of “clean” phase of ours, or some “clean” books. Wait and see! Hahahahaha!!!

Man, authors do what they like, we don’t impose any aesthetics… Otherwise it won’t make sense unless we were some kind of commercial publishers of sex& violence or artsy-fartsy-two-colours books, whatever…

Well, it seems dicks are everywhere in your comics! However, let’s talk about your activity at the Bedeteca de Lisboa (this is an unoffical website, the old address is now closed). I know you’ve a big collection of comics and that you organize events, classes and so on…

Used to… Since 2005 it’s just going down the drain as for others activities. Now, I’m just a good librarian dude in Bedeteca. If you go to Lisbon, please come by! It has a nice garden, good sofas and chairs, 9000 volumes of zines, mags, books, albums, CDs, DVDs and related items to comics and illustration. Why waste your time visiting tourist’s traps when you can come and relax reading books in Bedeteca? Actually we have books in Portuguese, English, French, Italian, Suomi, Swedish, Polish, etc…

The golden days of publishing, making big festivals, exhibitions and all that it’s gone (I did an interview in Stripburger about that) but the library is good and interesting, come on!

Since we’re talking about Portuguese comics, I’d like to know what is popular or mainstream in Portugal today. In Italy we’ve comics as Tex or Dylan Dog, published by Sergio Bonelli Editore, that represent perfectly the concept of “popular”, I don’t know if you’ve ever seen them… Then there is a large diffusion of manga, we’ve a lot of superheroes and a lot of satirical, ironic and in general funny (or supposed to be funny…) comics. What is “popular” in Portugal?

I guess humour strips are the most popular (Calvin & Hobbes, Dilbert, Adam, Cathy…). And then this pedophilic french-belgian stuff for the 40 uppers, fascist super-heroes for the 30’s up, manga for kids… Disney returned after some years, but maybe they’re selling to nostalgic grown-ups, kids aren’t that stupid to read that crap anymore. Many Portugueses read English, French and Spanish so they buy foreigner editions since the market doesn’t supply enough good books. We’ve also Brazilian editions of Bonelli trash, don’t know who consumes that and I really don’t want to know. I wonder if we can talk about a “mainstream” (excepts humour strips, I guess) because I know that Batman trade paperbacks sold as much as Baudoin’s A Viagem. I guess moronic Saga will sell better than these examples because it’s funny and, you know, comics are supposed to be… comical! Oh, the irony…

Can we say that 3000 copies sold of a book is popular or mainstream? I don’t know…

Moving from the popular to the personal, I’d like to hear from you some names of Portuguese cartoonists you admire and you can recommend to the readers.

Old and new all mixed up, active and inactive, dead and alive, with solo books or not: André Lemos, Janus, Ana Cortesão, João Fazenda, Nunsky, Filipe Abranches, Bruno Borges, Carlos Botelho, Pedro Brito, Pedro Nora, Amanda Baeza, José Smith Vargas, Jucifer, Pedro Burgos, Tiago Manuel, Rafael Bordalo Pinheiro, Francisco Sousa Lobo…

So there’s a lot to discover for foreigners like me… And on the other hand, what do you think of the European scene at the moment? I believe there is a greater and sometimes exaggerated attention to the aesthetic and formal aspects of the comics, probably thanks to the decrease of printing costs and the consequent diffusion of the color… I think this has influenced also the self-published comics, where now we’re finding a lot of conformist products, which are everything but alternative…

So there’s a lot to discover for foreigners like me… And on the other hand, what do you think of the European scene at the moment? I believe there is a greater and sometimes exaggerated attention to the aesthetic and formal aspects of the comics, probably thanks to the decrease of printing costs and the consequent diffusion of the color… I think this has influenced also the self-published comics, where now we’re finding a lot of conformist products, which are everything but alternative…

Yup, graphic novels made the comics looks like literature world: full of light literature, best-sellers and all that… You have to dig depper to find good stuff but that was always like that, no? People get nostalgic when they think they found Daniel Clowes or Joe Sacco in the 90’s and now there are all this Clowes and Sacco clones or subproducts but man, look at Canicola crew, or Glomp anthologies or some Serbian and Croatian guys and there’s still energy and originality to be as exciting as the 90’s. Or look to Olivier Schrauwen that actually can combine the “graphic novel loads of narrative pages to be respectable” with aesthetic and formal aspects at the same time. Or Ruppert & Mulot or Tommi Musturi… Or Jarno Latva-Nikkola who can be pigeonholed as “caricature” but has a full graphic novel depth…

It’s true that graphic novels are growing in the book market with “my mom was a crackwhore” or Pinochet biography, juts like best-sellers are now cook books or cats that saves the day… If all graphic novels were good (a thing that Fantagraphics or L’Association wanted back in the days) the world would be perfect, but as you know there’s still McDonald’s, war, hunger, latest Batman film, racism, Berlusconi out there…

As usual, we need critics – good ones – that can filter all this “new graphic books industry”, where are they?

If you want, I would close this interview speaking of your future projects. I read you’re setting up a lot of initiatives for the 15th anniversary of Mmmnnngggr, can you tell me something more? And what can we expect from Chili Com Carne?

15th MNRG celebrations are almost gone… We made a punk tour with two bands, released a split-tape and my new zine, Anton was in Lisbon in a conference with some public polemics and I’m DJing next week at Beja festival. After that it’s hard work making new books of Aleksandar Zograf, André Ruivo and Tiago Manuel… And something else that comes on the way!

As for Chili Com Carne we still don’t know… But we’re hoping to have new graphic novels of Francisco Sousa Lobo and José Smith Vargas, loads of other zines and books and some exhibition in Amadora Fest and University of Salamanca (Spain). But only after June we’ll have clear ideas…

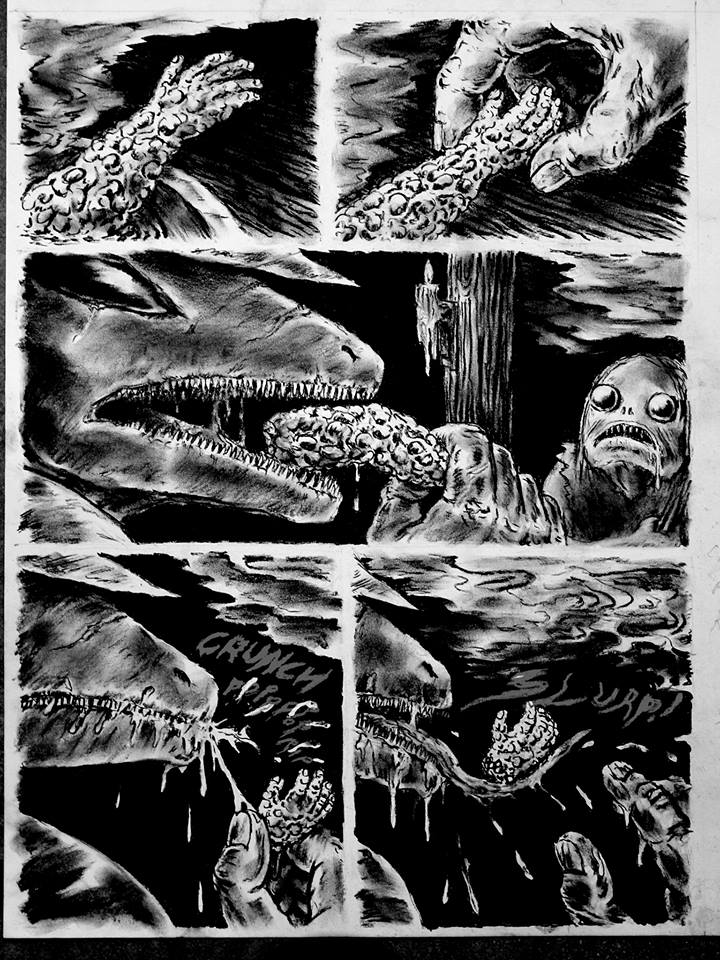

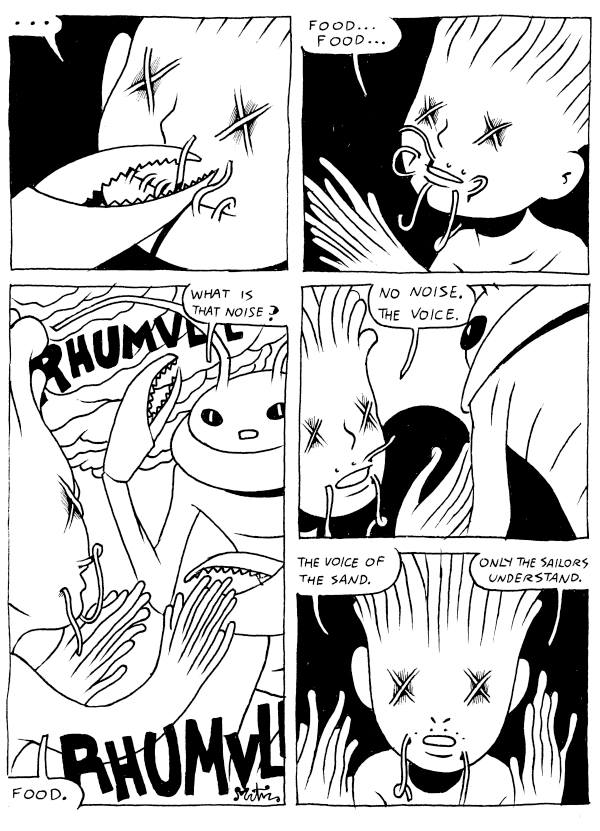

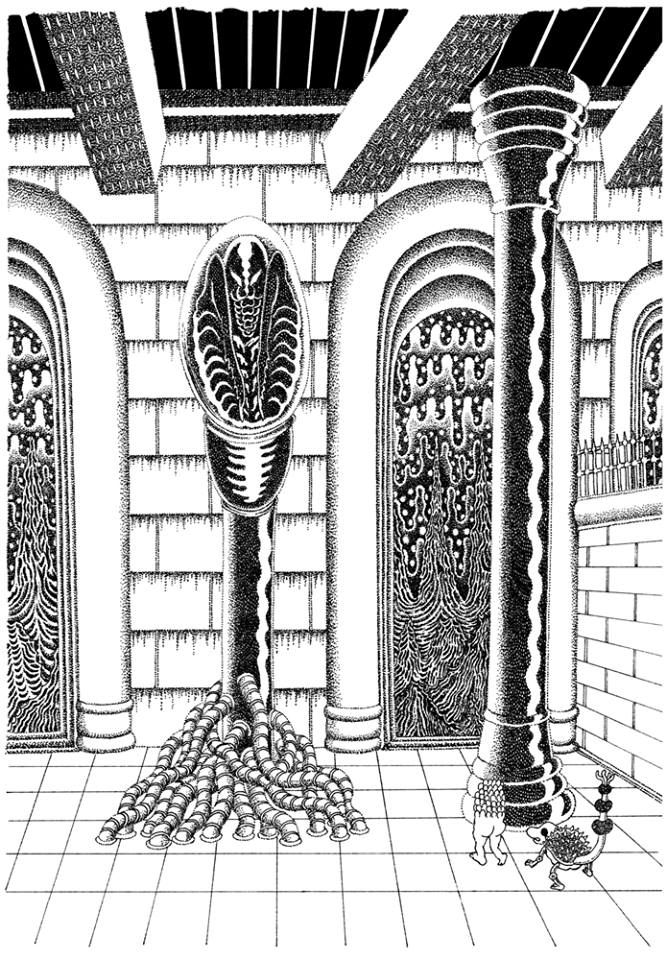

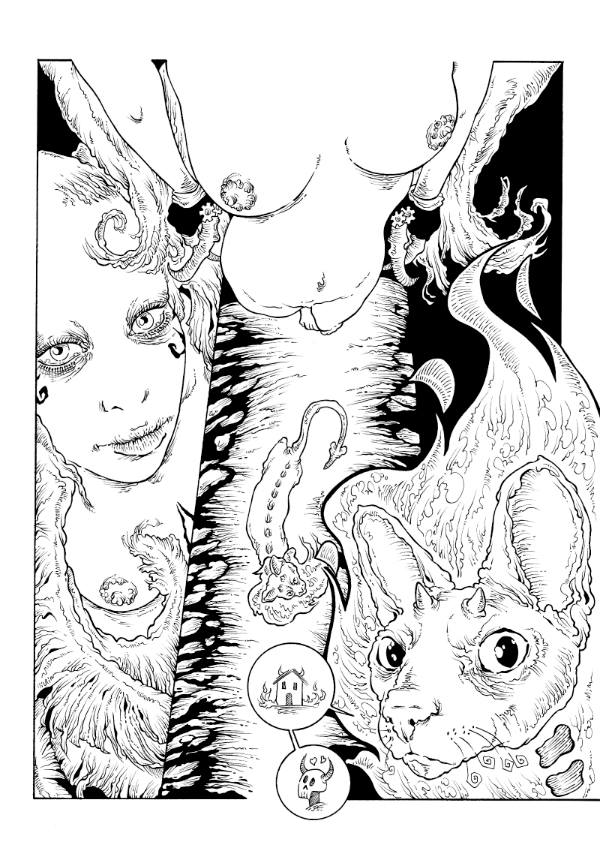

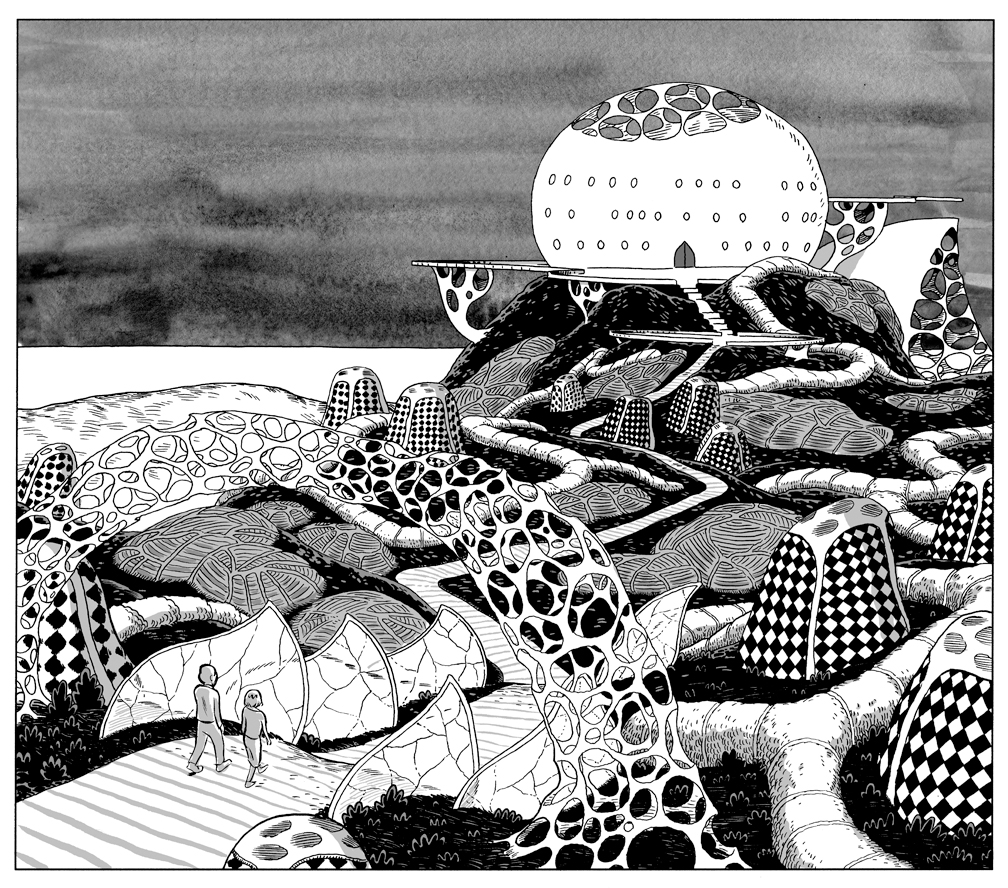

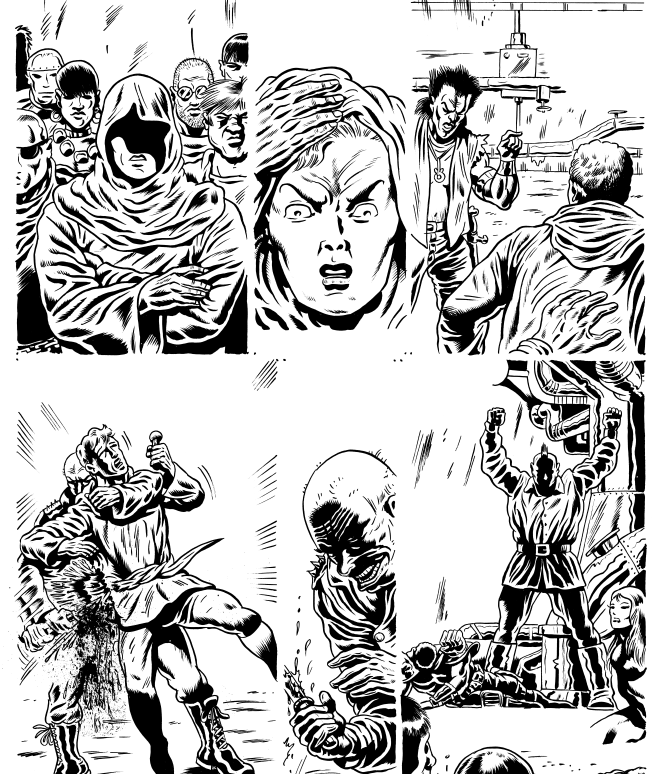

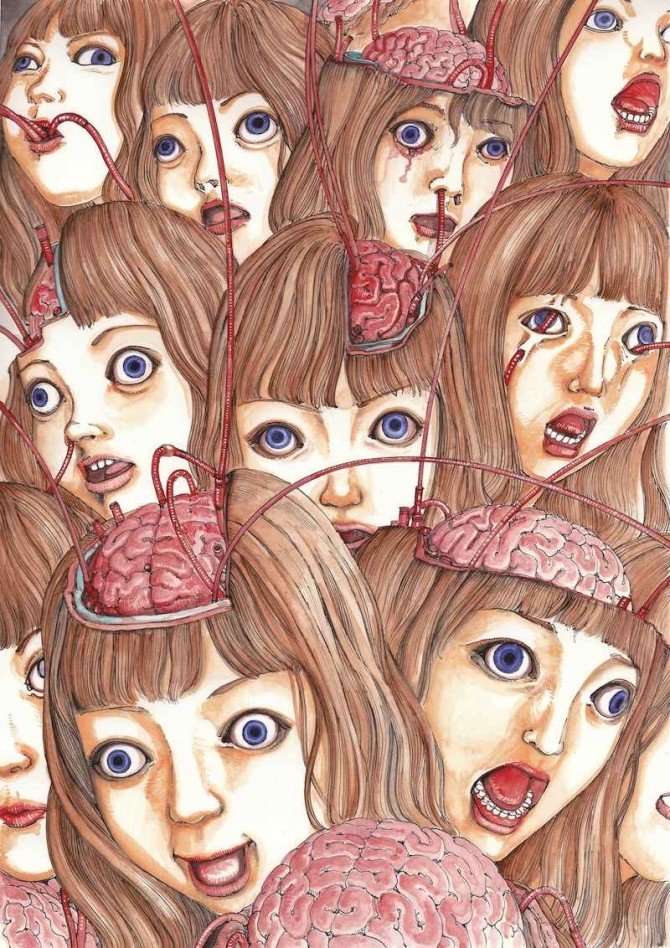

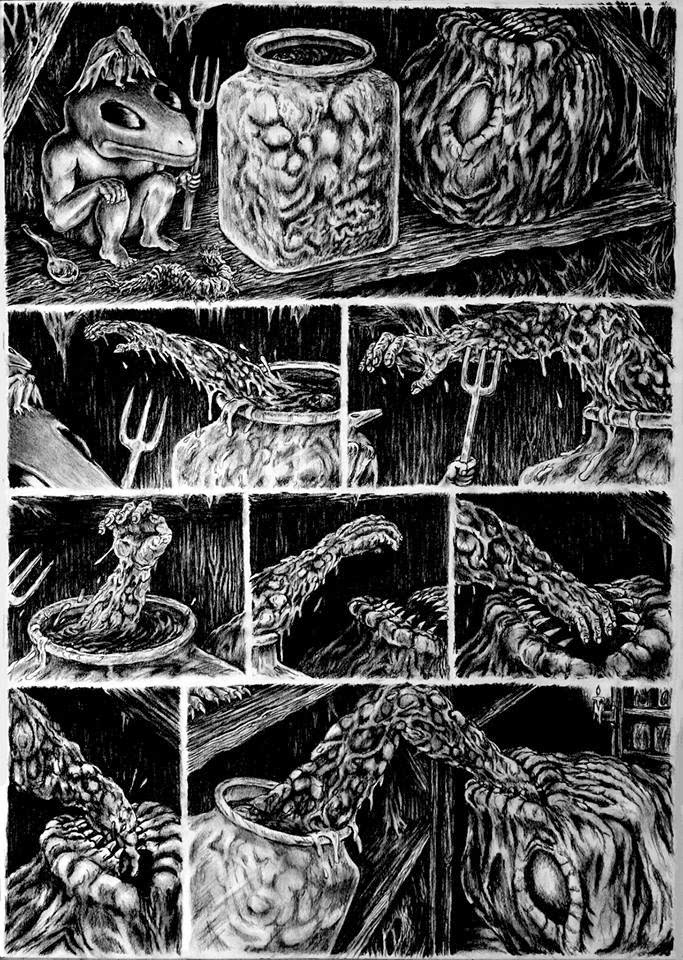

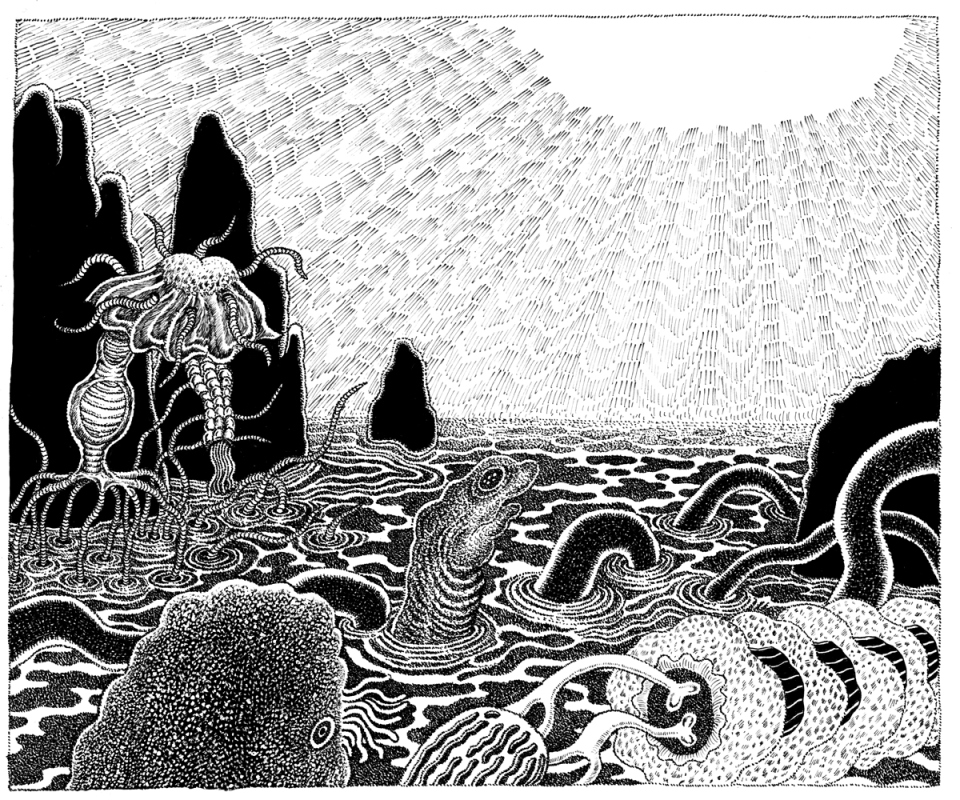

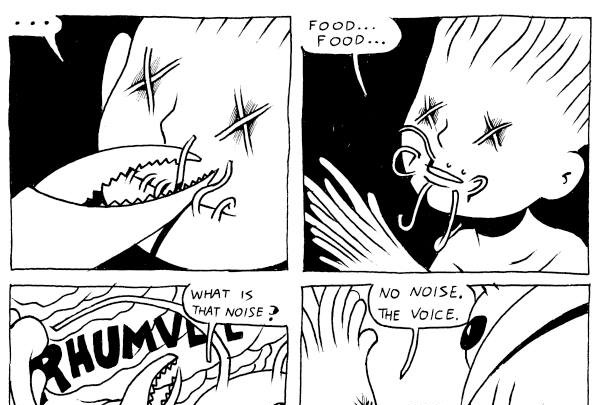

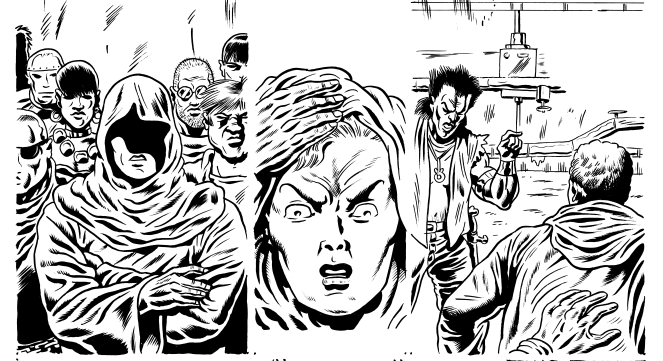

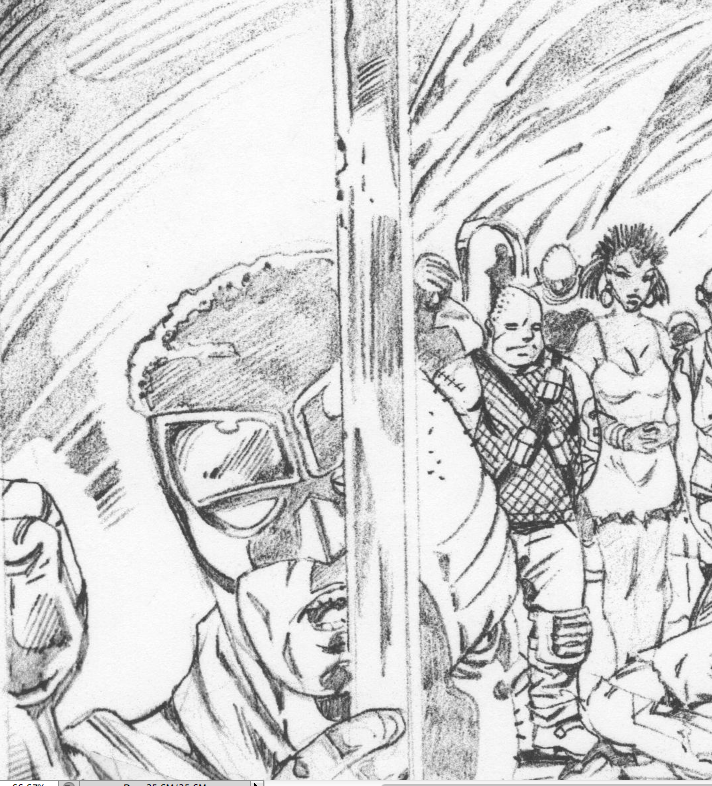

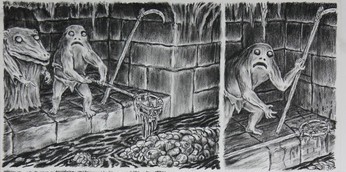

Five pages from “UDWFG” #3

I already talked about Under Dark Weird Fantasy Grounds several times, for example with this review of the debut issue, or putting the first two books in my best of 2014 list, or recently translating this interview with Michele Nitri made by Matteo Stefanelli for Fumettologica. If in the last months Hollow Press expanded its editorial projects with Industrial Revolution and World War by Shintaro Kago and Tetsupendium Tawarapedia by Tetsunori Tawaraya (here my preview), the third issue of UDWFG – initially due for April – has been delayed for the overwhelming commitments of a couple of artists. But now the comics are ready and in some days the new chapters of the stories by Mat Brinkman, Miguel Angel Martin, Tetsunori Tawaraya, Ratigher and Paolo Massagli will be printed. Below you can take a look at five pages, one per artist. Enjoy!

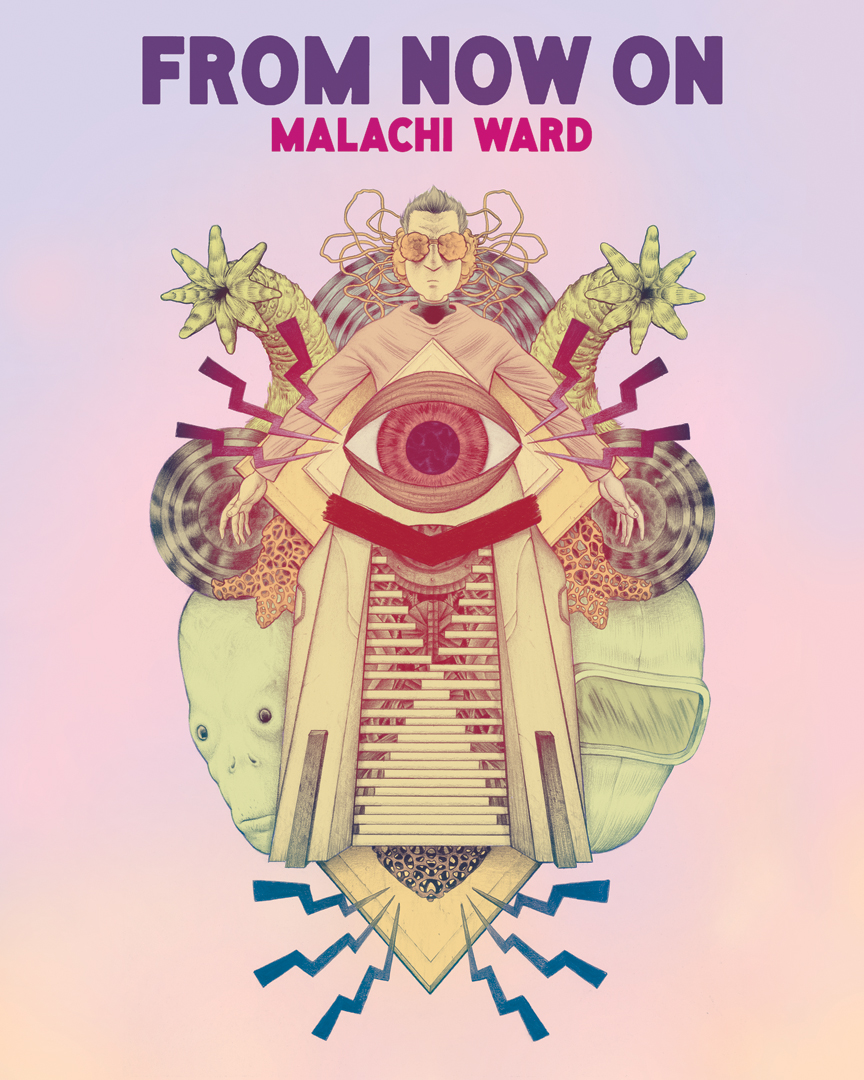

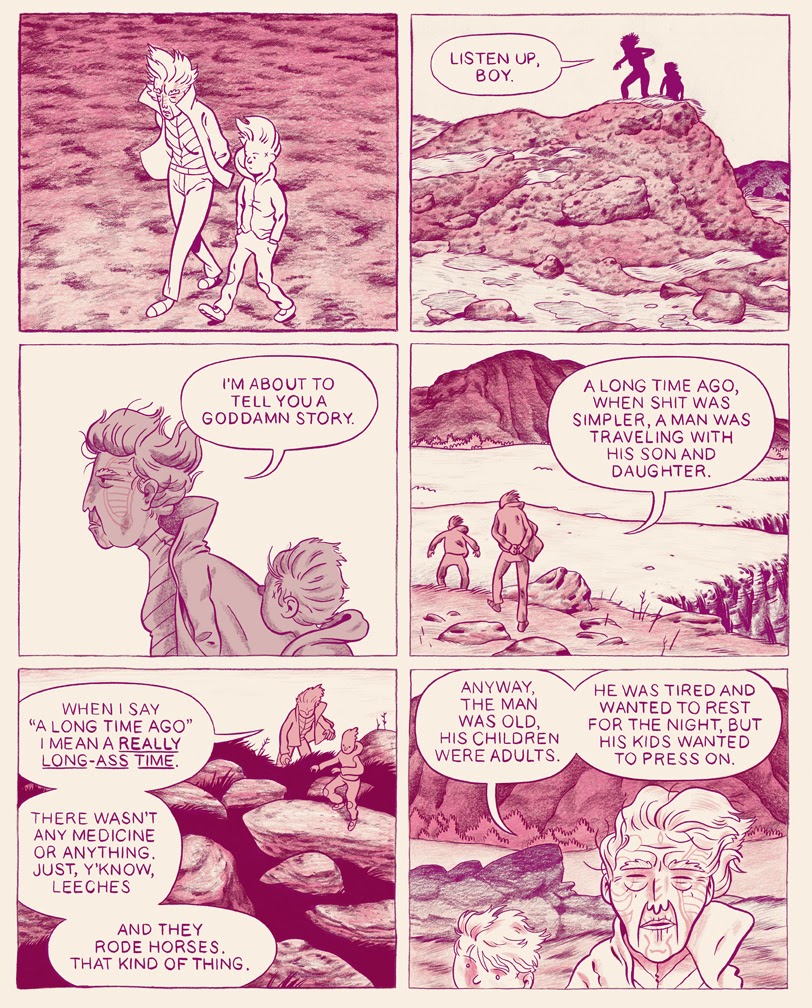

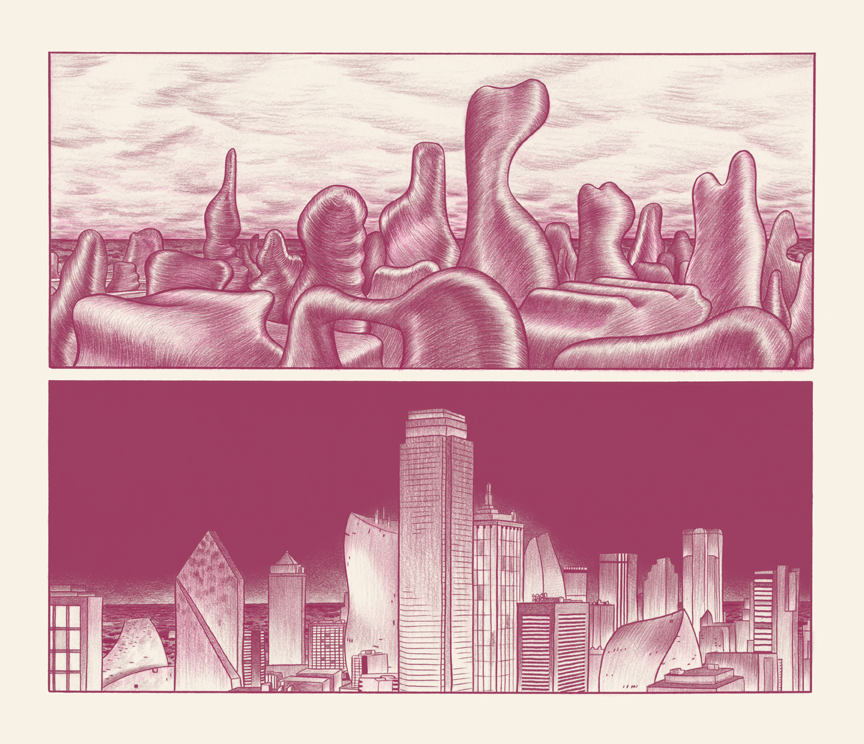

“From Now On” with Malachi Ward

Malachi Ward is the creator of Ritual, a series published by Revival House Press, and the author of From Now On, a collection of short stories which is coming in June from Alternative Comics. He also collaborated with Matt Sheean at the series Expansion and at some issues of Brandon Graham’s Prophet. The interview that follows took place at the end of May via e-mail.

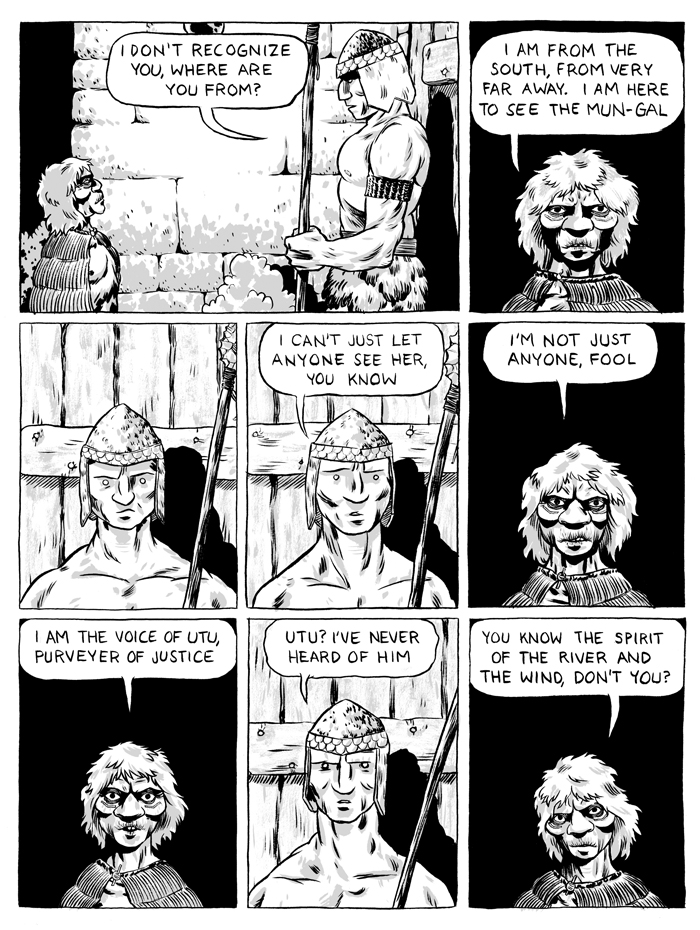

Since you talked about your formation as a comic artist and your inspirations in this interview with Dave Nuss, I’d like to begin this chat with some questions about From Now On. This is your first “book” and I think it would be nice to introduce it to the readers. I saw the summary and the very first story will be Utu, a sort of classic in your production, in fact it’s one of the first comics or exactly the first comic you printed. Do you think that self-publishing Utu in 2009 could be considered as a key moment in your career?

After college I was reading a lot more comics, and flirting with the idea of making them. Of course, “comics” can be almost anything, and I didn’t have much of an idea about what I wanted to do. My art at the time was kind of… whimsical I suppose? Anyway, throughout 2007-09 I kind of honed in on what I wanted to do. I started Utu in 2009, and traded off working on that and The Scout, for Jordan Shiveley’s Hive anthology. I finished them both in time for APE 2009. So both were a big breakthrough for me. It was the first work that I finished and was ok printing up and presenting to the world. I still kinda like those stories too.

I think Utu is a really original story, because it starts in a way and then moves in a completely different direction. And it has a lot of different registers, in the beginning it seems a sort of mythological tale, then it becomes funny and in the end it’s also sad in some way. I’d like to know if you started it with the intention to use different atmospheres and genres, or if the plot came out as a natural process.

One of the appeals to me of Utu was that bifurcation in the plot – that it feels like it’s one kind of story and then quickly becomes a totally different one. I’m not really into plot “twists”, but who doesn’t like a story surprising them, so long as it all fits? I’m drawn to that narrative device a lot… It’s something I often try to insert into a story, even if it doesn’t work! Each of the Ritual stories kind of has an element of that to varying degrees.

Before you mentioned The Scout, another story from 2009 that will be in From Now On, where you examined the concepts of time and repetition. This comic is based on a fixed grid of six panels per page and, watching your old things, you used a rigid structure several times. On the other hand, your recent work is based on a less regular layout. Do you think this could reflect your improvements as a cartoonist or it’s only a coincidence?

For The Scout, I was concerned with telling the story in as few pages as possible (since it was for an anthology with limited space) while still making it read naturally and not seem too compressed. I think keeping a regular panel layout like the one in The Scout helps with that. I did the same thing for another story in From Now On called Henix for similar reasons. I also think that the 6-panel layout just works well for a 5.5″x8″ mini-comic. While I certainly think I’ve progressed in my comics skills, I would still return to a rigid panel layout like that if it suited the comic. Even when my comics have a lot of varying panel sizes and arrangements, they usually follow regular tier breakdowns that I don’t deviate from.

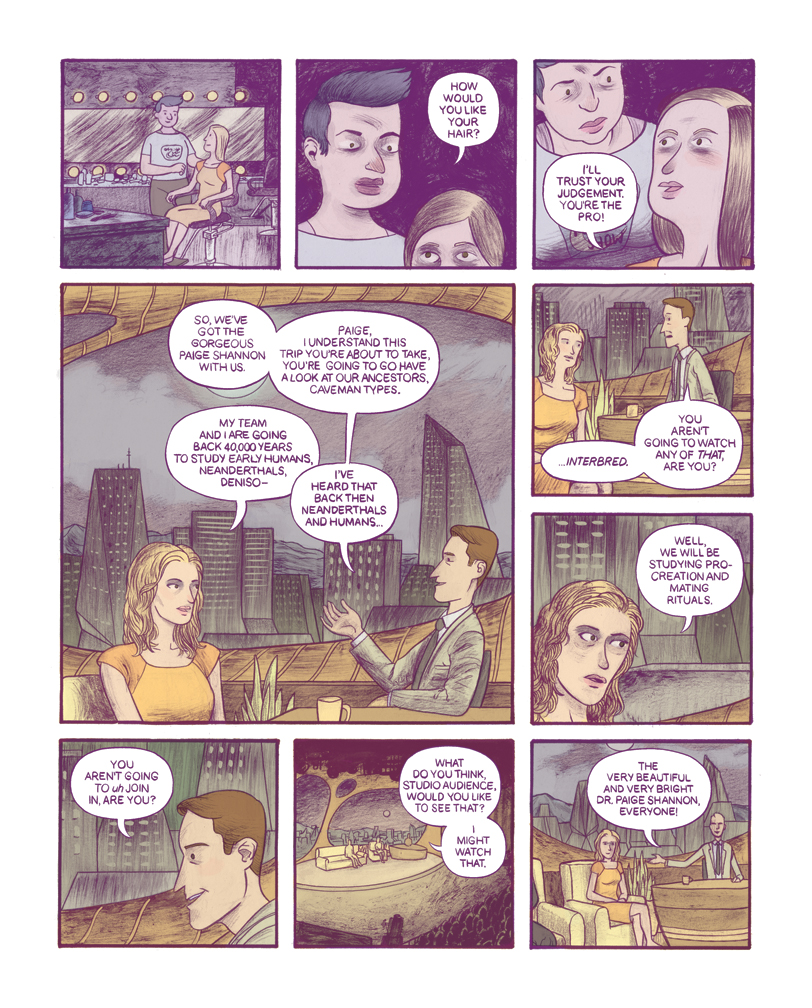

Another comic in From Now On is Top Five, a sort of metanarrative sci-fi story about Star Trek, definitely an inspiration for you. Sweet Dreams and The Oviraptor are also reinterpretations of some science fiction stereotypes. I think this is what makes your comics fresh and original, that you use some ideas taken from sci-fi movies and tv series but you treat them in your own way, creating a mix that isn’t so widespread in the world of alternative comics at the moment…

Sometimes, for me, a story starts with me thinking about how I might handle a genre trope. I think the goal is to find the core of whatever that idea is, the emotional element that clicks, the thematic or atmospheric qualities that could register with the reader, and then to work out from there while avoiding all the typical pratfalls a science fiction/fantasy/horror story can fall into.

Besides the ones we talked until now, I haven’t read the other stories in From Now On. Can you introduce them or some of them to the readers?

There’s a new full color comic called Disconnect (a preview page below, editor’s note), which takes place in the same world as Top Five, The Oviraptor, and Hero of Science. It follows one of the other characters that disappeared when the team jumped back in time. Some other stories include Beasts of Kay-7, which is sort of my take on a Star Trek type of a team that is exploring a new planet inhabited by mysterious monsters. Henix, which I mentioned earlier, is a high-fantasy kind of a story about a deformed (to the eyes of the main characters) prisoner with secrets about the royal family.

Let’s talk about Ritual now, the series published by Revival House Press, where every issue is a stand-alone story of 20-30 pages. Before picking up Ritual #2 – The Reverie, I had seen your work only online and when I read that story I was shocked… It was fucking good! Then I read others of your comics and I noticed that The Reverie is probably the most “serious” and touching comic you’ve made until now. And unlike the other issues of Ritual, this one follows a very linear narrative. I’d like to know how you came to tell this story, if it moves from your fears or from some nightmare you had.

Because The Reverie centers around a family death, it certainly contains a lot more emotionally potent situations than in my other work. Something like the death of a family member is frequently used as a cheap motivation for a main character, so I tried to be careful to imbue the build up and fallout from that event with as much empathy as possible. The idea for the story came from my fascination with the range of behavior a single person is capable of, and how opportunity shapes our ability to act in a moral way. It also deals with some notions of regret – I’ve heard people talk about what they should’ve done with their lives, or how they think things should’ve gone. It’s always been a profoundly alien feeling to me, something I have trouble understanding. It’s an idea that I’ll very likely explore with more depth in the future.

In The Reverie your drawing style seems less controlled and defined than usual. This is not a bad thing to me, because I think in some sequences you did a beautiful work depicting the landscapes or the rage of the main character. I think maybe you were doing some experimentation…

The first half of that comic, I think, is still pretty controlled. Everything that takes place outside of the titular dimension is inked with a brush and pretty carefully drawn. I actually didn’t have much time while I was working on the book, and most of the second half was drawn over the course of a couple weeks. I knew that I wanted to change the style a bit inside the wish dimension, like inking with a pen instead of a brush, but because of the limited time that part of the story also took on a much looser quality.

Ritual #1 – Real Life and Ritual #3 – Vile Decay are quite similar in the structure, while for the contents Real Life is – as the title tells itself – a true life story turning out in a very frightful way and Vile Decay is about future and how people are fucking up the world. As a whole this series talks about a lot of big themes, as family, relationships, death and – in issue three – also politics and ecology. But I think all three issues of Ritual so far are mostly talking about your fears. Or this is the way I see it…

My starting point for the Ritual series is that it’s a horror anthology. Really, I only think Real Life ended up feeling anything like something one would identify as part of the horror genre, but every entry is certainly related to fear in a fundamental way. Real Life is inspired by actual nightmares: my wife hatefully abandoning me, and me turning “evil”. The Reverie kind of spins out from that, I was thinking about how easily I could succumb to being a pretty scummy person if the right situations presented themselves. Vile Decay, while ostensibly about the degradation of society, was more about my fear that I’ll completely disconnect from the world as I grow older and it becomes easier to do so.

Another way to read Ritual #1 and #3 is as pilots of a tv series, but your comics will never have a follow-up, so the reader has to imagine it or try to interpret the stories browsing through the pages…

Ritual #3 has an especially elusive narrative quality to it… it could be a very unsatisfying read for a lot of people. I think there’s enough in that one that a person can unpack if they think it’s worth it, so hopefully the comics invite the ready to do that. In the next group of comics I’m making I’m kind of reacting to that (something I tend to do for whatever reason) and creating stories that have much more definitive resolutions.

In this group of comics there is also Ritual #4?

I’ve got a pretty detailed outline that I’m really excited about. Right now it’s just about finding time in my schedule to actually draw it. Ritual #4 is tentatively titled The Left Hand Path.

So it could be about your fear of becoming left-handed…

How’d you know??? That’s my real deepest fear.

Do you think the new issue will use two colors as the previous? I loved the pinks and the oranges of Vile Decay, they contributed to create a nebulous and unreal setting.

I think Dave Nuss and I are planning for Ritual #4 to be printed in full color, but it will retain a limited palette.

I know you are working on a couple of new projects with your friend Matt Sheean, with whom you already collaborated for Expansion and for Brandon Graham’s Prophet. I know you and Matt are totally sharing the different tasks of the creative process and I’m curious how you’re doing this.

For the project we’re currently working on (Ancestor, which’ll be part of the Island anthology for Image) Matt and I break the work down like this: We both talk through the plot of each issue and come up with an outline, usually together. If the outline calls for any important chunks of dialogue, we each take a sequence and write it out. Then, over the course of a couple intense days, we do thumbnails for the whole issue. From there Matt pencils, I ink and do flat colors, and Matt adds lighting effects to the colors. I then letter the final page.

This is a very interesting way to develop a collaboration… Ancestor will be a long story?

Ancestor will end up being longer than anything I’ve done in awhile, probably about 120 pages when it’s done.

Besides Ancestor are you working on other long stories or you’ll going on with short ones?

Currently I’m thumbnailing a full color comic that’ll be around 80 pages. I’m planning to do mostly longer stories from this point forward.

I’d like to conclude talking about what is exciting you at the moment, if you’re listening to some music in particular, or if there is a comic or a novel or a movie you enjoyed a lot recently…

I just reread the Lawrence Wright book Going Clear and I’m pretty obsessed with it. I’m doing some research about Indo-European culture that’s really interesting. In the comics world I thought Jillian Tamaki’s Sex Coven story for Frontier was really inspiring and fantastic. Same goes for the newest issue of Crickets by Sammy Harkham. I haven’t seen many movies I really loved this year, but I really liked Ex Machina, and I thought Mad Max: Fury Road was a lot of fun. I’ve been listening to the 1988 album Encounter by Michael Stearns while I write, as well as a lot of Jean-Michel Jarre.

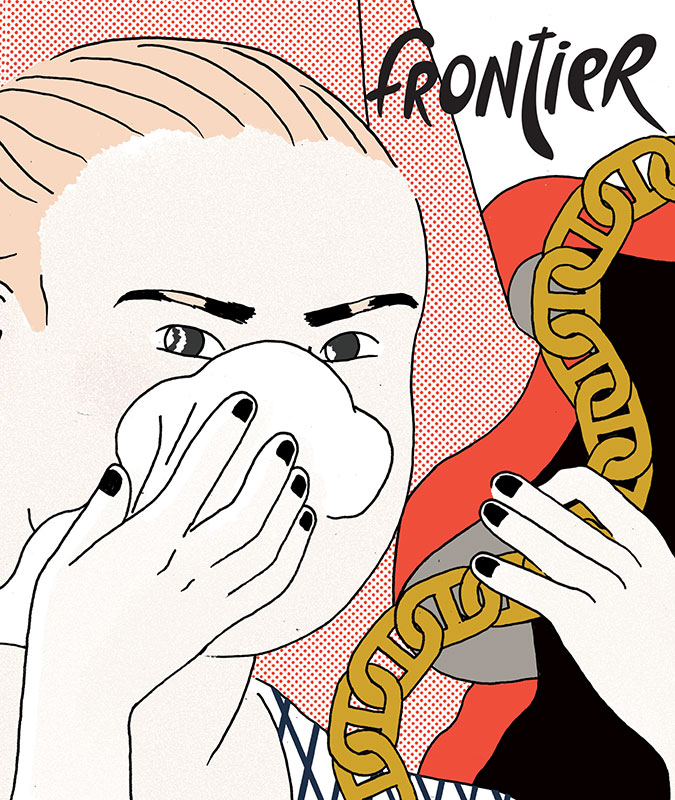

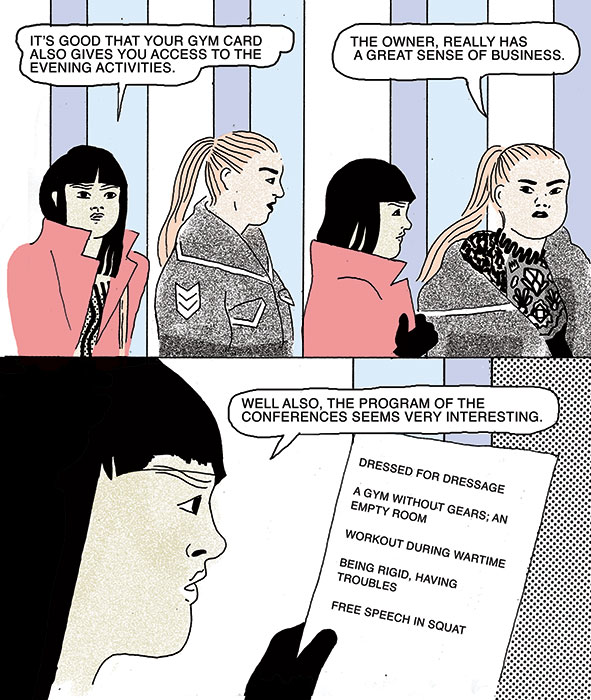

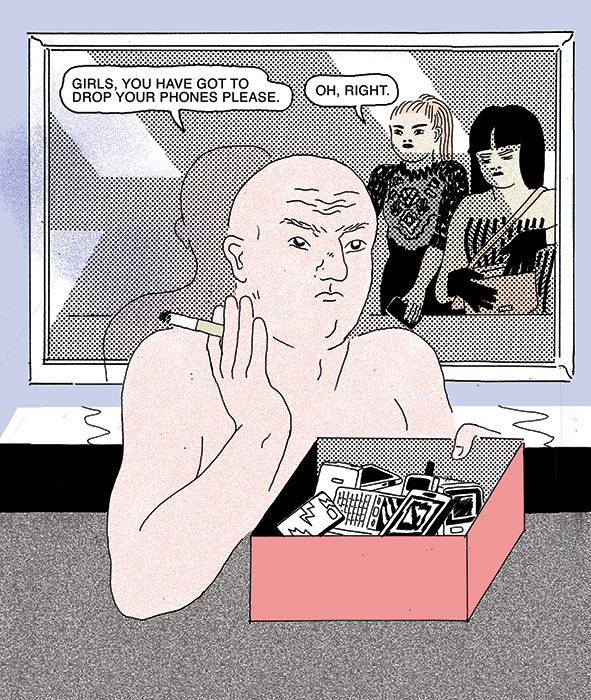

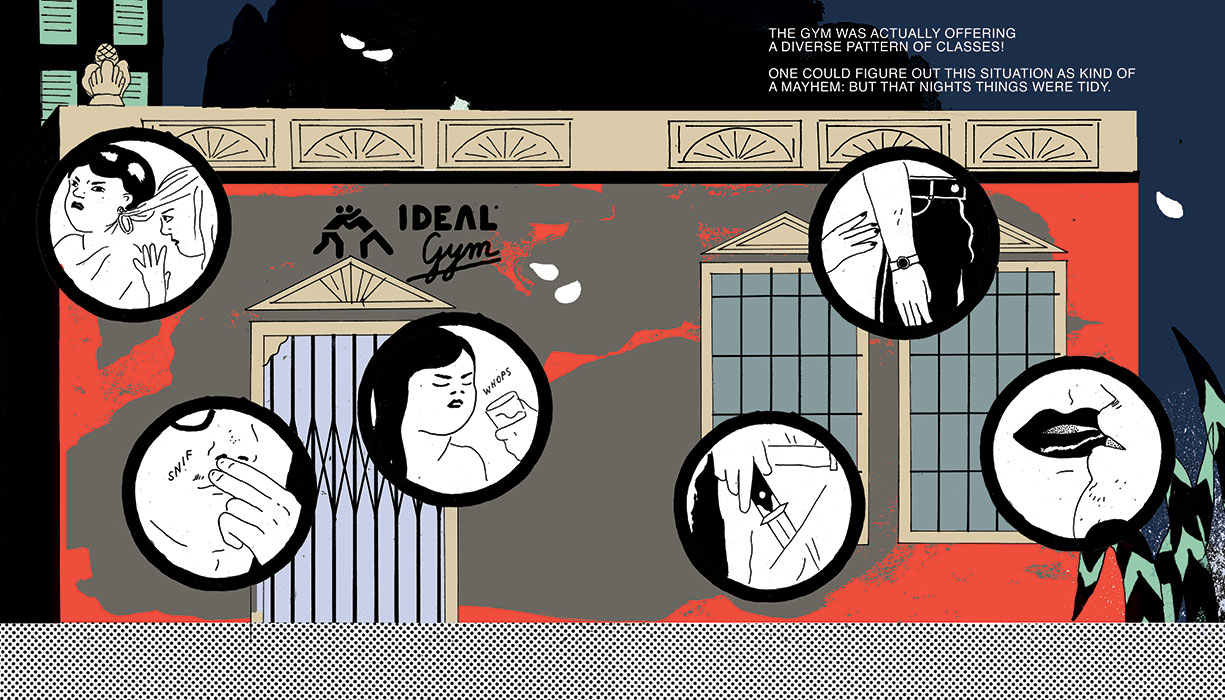

First look at “Frontier” #8 by Anna Deflorian

Italian illustrator Anna Deflorian is the author of the newest issue of Frontier, which debuted at Toronto Comic Arts Festival last weekend. Ryan Sands, publisher of San Francisco-based Youth in Decline, discovered Deflorian’s work thanks to her contribution to the ninth issue of Baltic anthology š!. The themes of that comic and the disquiet, the desires and the hidden emotions of the girls drawn in Roghi – a book published by Canicola Edizioni in 2013 – return in these pages. Two women, a man met in a gym, a lost phone full of “filthy” pics are the elements of a story illustrated with densely decorated pictures and an unusual sense of geometry. Below the first pages of Faith in Strangers.

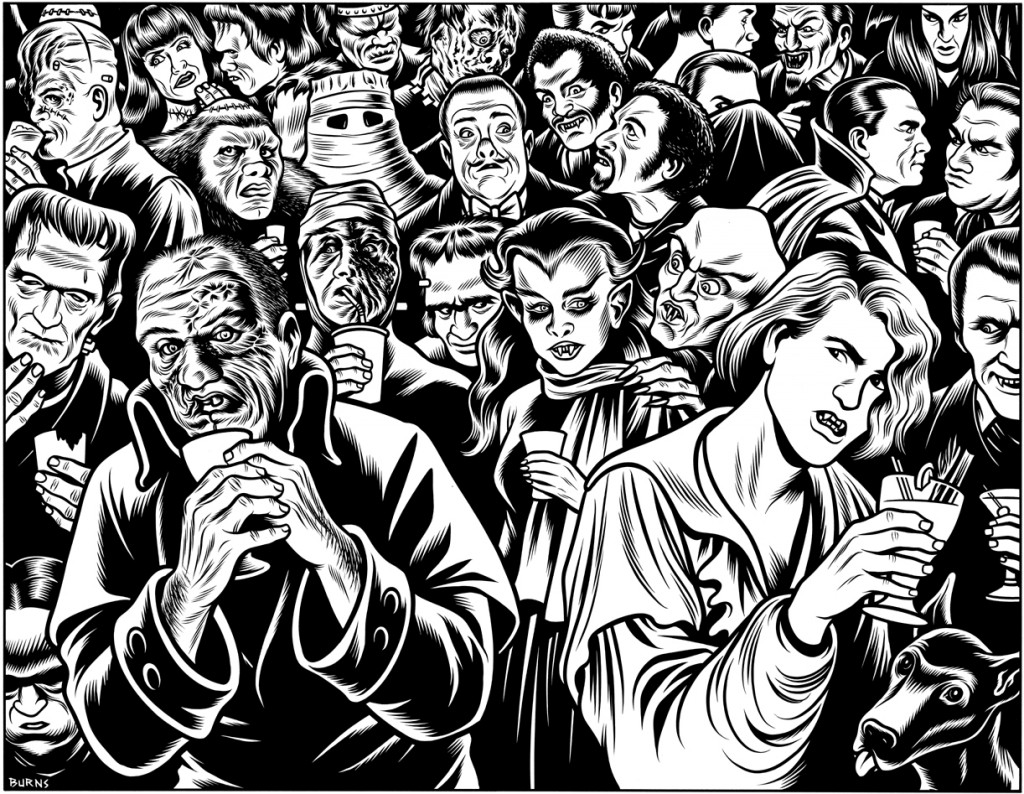

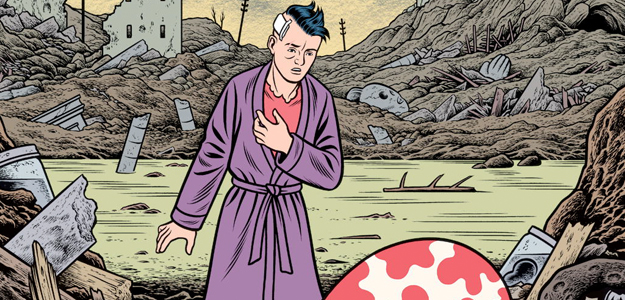

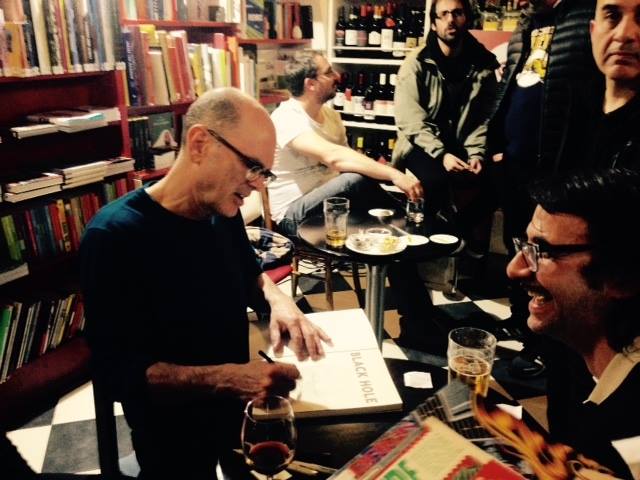

An evening with Charles Burns

On Thursday 19 March Giufà Bookshop in Rome hosted a panel with Charles Burns. Black Hole‘s creator came to Italy to accompany his wife, artist and painting teacher Susan Moore, just as he did in the Eighties, when the couple spent a few years in Italy and Burns joined the Valvoline group (he spoke about this experience in this interview with Darcy Sullivan). The evening was an opportunity to introduce the American cartoonist to Italian readers, deepening his creative process and the themes of his comics. Novelist and journalist Francesco Pacifico translated the conversation while comic critic Alessio Trabacchini and Italian cartoonist Ratigher asked the questions. At the end of the discussion, Burns signed and drew sketches for hours, showing an extraordinary willingness. I’ve translated and sometimes summarized the questions, whereas Burns’ answers are (more or less) his original words.

Alessio Trabacchini: Charles Burns knows how to tell complexity. He found a narrative form and a line to tell the ambivalences of feelings and of the entire world. I would like to ask how he managed to tell a particular aspect of human life, the one related to sex, sexuality, beauty and desire. In Black Hole there are some of the best representations of sex ever seen in comics. So I’d like to know his approach to this aspect of human life and to its representation.

Charles Burns: When I finally reached the point in my life where I felt comfortable about expressing something very personal, I wanted to be as free and open as I could. Sexuality is in everybody’s life but I didn’t want to do something that was purely gratuitous, purely pornographic. I wanted it was a natural part of the story. So, for example, in Black Hole there is a very strong scene but the entire story is not gratuitous, is not about provoking someone or making something that is titillating. I like the idea that in a three-four hundred pages story you would have ten pages focused on something that is very strong. There are moments when I was writing stories that I felt like “I don’t know if the world needs to see my vision”. It seemed too dark to me sometimes, but I wanted to be as honest and open as possible. I think in earlier works I wasn’t aware of it but I know that I was censoring myself, stopping myself from ideas that were very strong and maybe disturbing, but I tried hard to push that away, to make something strong and honest… And if I’ve to be honest I’ve never met a woman with a tail…

Ratigher: My first question is similar but on another aspect. I consider Burns the cartoonist who depicted the occult and the bizarre better than any other. He’s for the comics what is Lynch for the cinema, they are the keepers of mystery and nightmare. I’d like to know if he thinks to have reached a new level over the years, if he had an evolution like in the role-playing games, from an occultist – a fan of bizarre and dark things – to a wizard with the power of frightening people, making books with dark forces inside.

Burns: I find that my stories for whatever reason move toward the darkness, but I’m not intentionally trying to scare someone. Growing up I was attracted to a darker side of America, an underside of American culture. There is a facade that I grew up with where everything is ok, but underneath that sometimes there is a dark underside. I was always interested in that facade and what it represented. And I was interested in reality, the reality I grew up with, the reality that I felt and that had nothing to do with the status quo and with the normal vision of a happy and secure family. None of my stories is very happy.

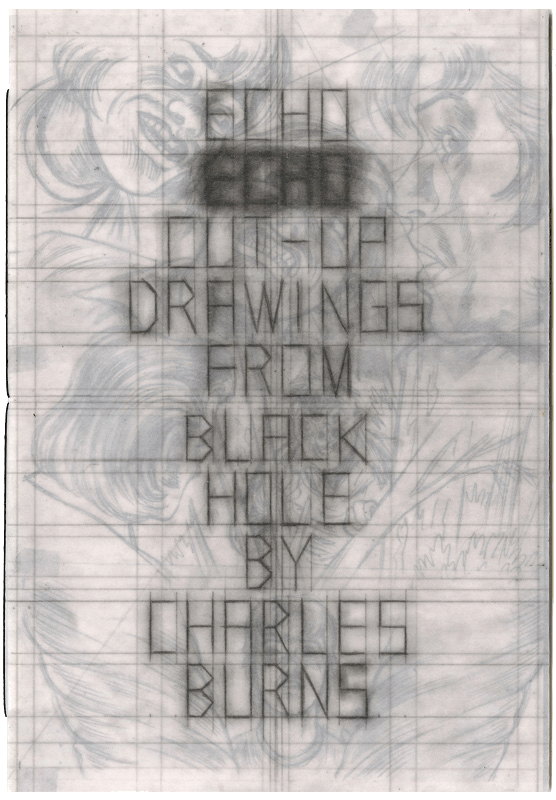

Trabacchini: Another thing I’d like to ask is about the line. Your style is very sharp, with strong contrasts of black and white. Even if there are a lot of shadows, it seems a personal version of the French ligne claire, an explicit reference in your last trilogy, where you created a dreamlike world that is a sort of mash-up between William Burroughs’ Tangeri and the setting of Herge’s The Crab with the Golden Claws. Then I was looking at this one again (Echo Echo, a collection of preliminary drawings from Black Hole) and it’s interesting because it shows how you arrive at your ligne claire, with a series of lines, marks, sketches. And this strong and instinctive way of drawing becomes the restrained and well-defined style of Black Hole, so distinctive to remain coherent and uniform in ten years. The pencils of Tin Tin have this same peculiarity, they’re full of marks and crossed lines but then they come to something clear and precise. I’d like to know how Burns works to create his own line.

Burns: I think my work was emulating ’50s and ’60s American style I saw very early… Harvey Kurtzman, Mad Magazine…. There is this style with very thick, beautiful dark lines. On the other side of that, it was a very unusual situation for an American of my generation to see Hergé and his beautiful ligne claire, the colors, the characters… So, I was always very attracted to Hergé and the clear line, but my style definitely makes towards this very dark line with the brush. It’s been pointed out to me that when Hergé was drawing he had this very rough, open line. He started with drafts and then distilled, distilled, distilled down to a very specific line. The book you’re showing is a collection of preliminary drawings, some are very clear but some are more rough, very gestural… They start from a very gestural idea and then are refined and refined as I work.

Ratigher: I also have a question about the style. I think his drawings show a high technical ability and this is one of the reasons a lot of people like his work. But his illustrations are also narrative, he doesn’t draw to show off his craft, every panel tells a piece of the story. Even when he draws a face, the reader can imagine the life of that person. I’d like to know if this is true and how he worked on it.

Burns: For me comics are all about the story. I know that people look at my work and say “look at this line, look at the drawing ability” or something like that, but the story is always most important. Telling a story is a distillation, it starts with something very draft and refining, refining, refining. There are moments when I want to draw a beautiful picture but if that beautiful picture is not part of the story I can’t put it in the comic.

Ratigher: But I’d like to know if this was a natural and innate skill or he had to reason about it, because it’s rare to find artists that are so technical and also narrative. Perhaps only Robert Crumb has this kind of control on his drawings, always detailed, elaborate but also devoted to the story. I don’t know if Burns had to work on this aspect of his art or if he was born with this ability.

Burns: I was born with nothing… “niente”. I think there are cartoonists that start on a very visual side and cartoonists that have a very literary side. I started with the visuals and I needed to teach myself the language of comics to tell a story. I’m turning sixty this year and I still don’t understand it… But I’m trying. When words and images come together perfectly, the images become invisible. You’re IN THE WORLD, you’re not thinking to technique, you’re not thinking “oh, this is a beautiful line”… You’re immersed. It’s the same way with the good movies, with the good novels, with anything. The techinque becomes invisible.

Pacifico: At this point I’m asking if you can give us some examples of movies or novels where the technique became invisible. I’m thinking about the latest movie by Paul Thomas Anderson, Inherent Vice, where it seems he deliberately wanted to delete the idea of a director that shots big and structured scenes to make us feel only the plot.

Burns: It’s always impossible for me to point very directly to influences but I can talk about the technique, the lines, the look I liked in some specific comics. Actually I could be influenced by everything. In my case I’m trying to do my best to tell my story, it’s not Ernest Hemingway’s story or Nabokov’s story, or Murakami’s story.

Ratigher: But what I’d like to know, coming back to my latest question, is if Burns sometimes sits down and draws something that isn’t a comic, that isn’t narrative. If it happens sometimes he likes a flower and decides to draw it.

Burns: I would love to do that, but no. Unfortunately it is a slow, slow process. For example, my friend Chris Ware told me he has a large sheet of paper and he starts drawing. This is impossible for me. I have notes and notes and tiny drawings and everything. There is nothing natural about my process. It’s very slow. I think my life would be much more simple if I had this direct approach but it’s not possible.

Valerio Bindi (Italian cartoonist and coordinator of Crack! Festival): I remember Gilles Deleuze said about Lewis Carroll that he was wide but not deep. I think Burns is both wide and deep, because he accurately builds the structure of the story, that has many layers – adolescence, wood, metaphors, dark places – but at the same time his drawings are fascinating for everyone, and this makes his art wide. For my generation of cartoonists who started making comics in the ’80s, he is the artist who took the themes of ’50s and ’60s in the underground, creating a cold, clear and synthetic style. Now I think the underground has moved from Usa to Europe and that people from Usa are mostly following the European underground movement. I’m asking what he thinks about it, if he sees an underground today and if yes where he sees it.

Burns: For me, growing up, my sense of underground was being thirteen or fourteen years old and discovering Robert Crumb and comics that moved away from the commercial world, something vey self-expressive. I think early they were transgressive because they had to deal with sex, drugs, politics. I think now it’s established that you can write something very personal and it doesn’t have to fit in a genre… I don’t know if the world of underground comics ever existed. Underground seems very inaccessible but for me, growing up, I could take a bus and find a store and get every Zap comic, Robert Crumb’s comic, every hippy comic and later every punk comic. I like the idea that someone who is in his twenties has no idea who Robert Crumb is, has no idea who I am, looking at something new, moving in other directions. There is no need to know the classics. I’m not interested in a young artist who talks about his influences. It’s a pleasure when everything moves on… When I was younger I remember Art Spiegelman, my close friend, saying that we had to move past Will Eisner. The underground is someone seventeen, eighteen, ninetheen, twenty years old who has never heard of me.

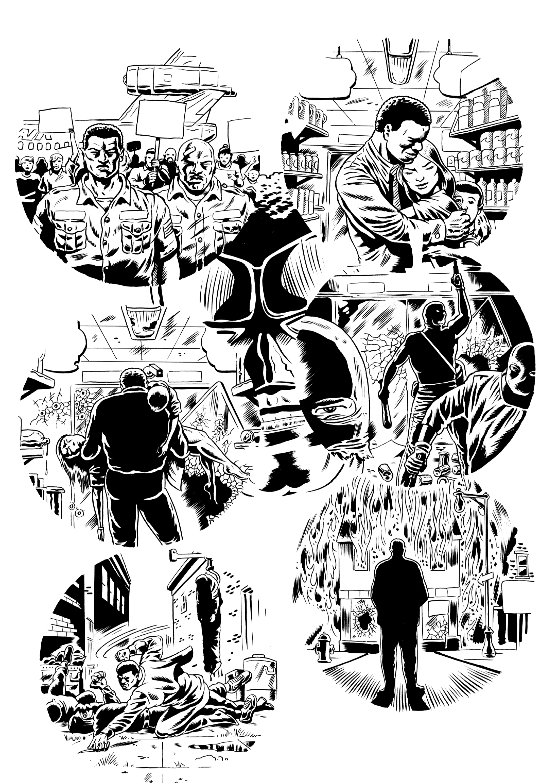

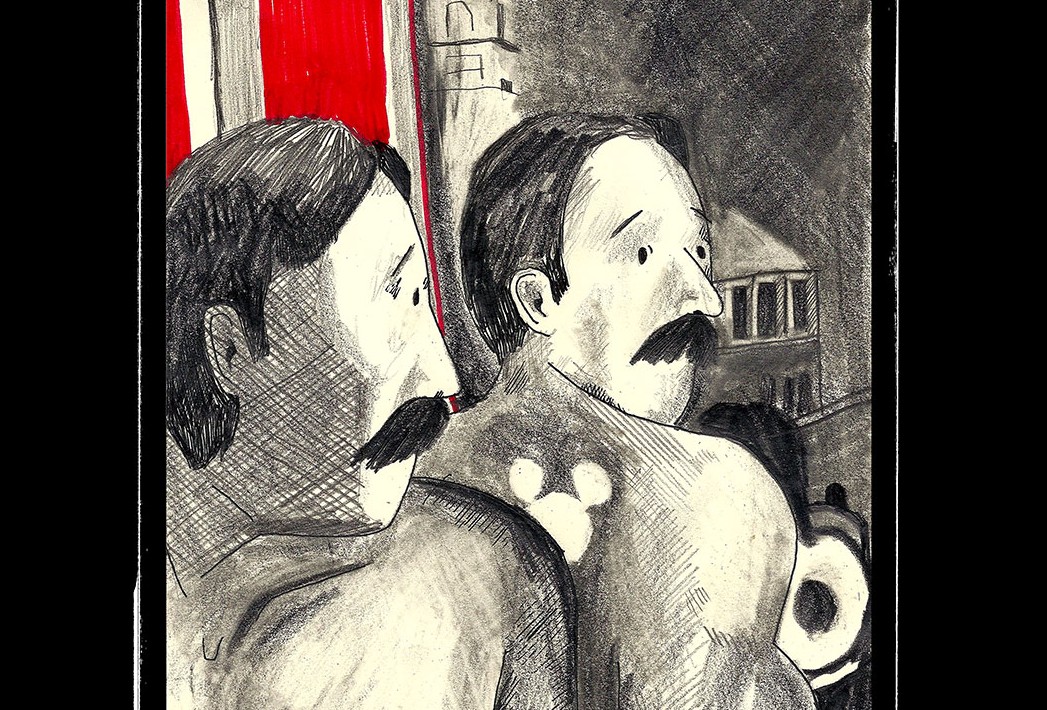

Herb Trimpe’s last great comic

Herb Trimpe was one of the most important artists at Marvel Comics in the ’70s, mostly known for his work on the series The Incredible Hulk. Trimpe died on April 13, 2015, after completing a story for All Time Comics, a new line of books created by New York-based cartoonist Josh Bayer, editor of Suspect Device and author of comics as Raw Power and Theth. Bayer is a huge fan of Marvel comics from thirty-forty years ago and he also created his own bootleg stories, starring Rom, Conan and the cartoonists of the Marvel Bullpen, often denouncing the way creators as Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko and Steve Gerber were treated by Marvel industry. Some scenes from his comics include Steve Ditko screaming “Marvel and Disney… are the government!” and a girl surrounded by Deathlok, U.S. Agent, Howard The Duck and other characters saying “Face it. Around here, we’re as disposable as the pencilers, inkers and writers who make up the Marvel Comics industry itself”.

This is how Bayer remembered Trimpe on his Tumblr. All the pictures are from Crime Destroyer Giant Size by Josh Bayer, Herb Trimpe and Benjamin Marra, due out by October 2015.

“Last year I contacted Herb Trimpe and asked him to draw a book for a line of comics I’m editing and writing. We were able to offer him a decent page rate and astonishingly he said yes and I’ll be publishing later this year what is (as far as I know) his last comic. Trimpe’s work was everywhere when I was growing up, in reprints and in current books on the stands, and his swaggering, cartoony, monolithic, half-rickety, half-fluid characters were ubiquitous with what I thought comics were. He maybe was one of the first people I saw who liked to make his characters WIDE, the chunkiness that is so fun for cartoonists to express (everyone from Frank King to Crumb to Gary Larson is part of this tradition) is intact in Trimpe’s pencils. The mouths were wide, the faces were wide, the fingers were wide. He was a Kirby protégé and was smart and humble enough to be proud of his ability to swim alongside his heroes without seeming to aspire to greater heights. It seemed to be fulfilling enough to be a steady artist, a provider for his family, a vet who served in Vietnam, and a deacon in his church.

Kirby was a leader, and Trimpe was like a soldier, but as much as he might have recognized himself as merely a professional, skilled at drawing everything from technical equipment to horses to architecture to sweeping urban panoramas, he wasn’t merely a dependable illustrator. He also drew with the inventiveness and enthusiasm of a kid. A freedom that many artists will never have. Looking at his work, you know his personality as much as you know R Crumb’s. It’s warm and familiar. The correspondence he creates between the reader and the work is more like Crumb or Basil Wolverton than many of his slicker, smoother peers. And like Crumb, his stuff might reflect the real world at times, but it’s never gonna let you forget it’s a cartoon.

As photocopies of his new pages began to arrive in my email last year, I was so heartened that in his seventh decade he was doing such peak work, full of the transitions, lighting and sequencing he was known for. “I have to tell you, I’m having a ball… it’s the most fun I’ve had doing non mainline work”, he wrote to me, and I was so glad. I would be happy for days every time I heard from him. I kept looking at the work. The lines were confident and powerful, his storytelling brimming with the sort of visual inventiveness that results from having completed thousands and thousands of pages of work before we connected.

To me, getting approval from him, and from other professionals like Rick Parker and Al Milgrom, has been everything I’d hope for in comics, a seamless circle between the past and future. Only in a lopsided industry like this one could someone in my position at the low end of the ladder attract a string of creators with decades of experience and accomplishment behind them.

Trimpe’s work helped to keep the American industry afloat, in a very visible way. He was one of the top six artists at Marvel and one of the most steady and visible. He slowly was eclipsed by younger artists, but his contributions were undeniable and should have set him up for life. Last year, a page of art appeared on the market by a collector who had been hoarding it for 35 years, the final page of Hulk 180, showing the first appearance of Wolverine, which was inscribed to the collector by Herb. Apparently it had been given to the collector by Herb himself in 1983. The art resold for over 600,000 dollars, breaking a record for original comic art sales set a few years prior by a Frank Miller Batman page. The collector had said he was going to give a large portion of the money to an organization for older artists and I’d been hoping he secretly was going to give the money to Herb Trimpe to counterbalance the way he never took part in the massive profits his life work generated for the industry. I don’t know what the result of the sale was but it would be so satisfying for Herb to know his work had brought about a long term security for his family that was the dream of almost everyone in his generation.

A lot of my own comics are about creators of the past. I’ve always been fascinated with how people face age and the changes life brings on in its third act, and the difference between the face of public figures and their interior life. I’ve done stories interpreting a fictional version of the Marvel Bullpen, showing my versions of Steve Ditko, Bill Mantlo, Bill Everett and Stan Lee, and mostly they are protest cartoons about the way creators are treated as disposable. The whole time we worked together I wondered if Herb ever saw the comic I did about him, “Trimpe Survives” (earlier published as “Trimpe Loses”), that I did in 2011, a year or two before I contacted him. I kind of doubt it, but you never know.

It detailed a metaphorical battle by Herb to stay alive in a barren wasteland, surrounded by flesh-eating Image Comics-style adversaries. The comic ends with Trimpe, determined to outlive the younger predators waiting on the horizon and drawing, (as he did in 1992), an issue of a Fantastic Four Unlimited in the style then made popular by his younger competitors. This instance of a creator of his stature attempting to stay current when work was disappearing is just wrong. I never forgot it.

When we began to collaborate, I was afraid he’d think I was making light of a painful period of his career, and that I was taking a shot at him. I never broached the subject. The vibes were running positively and I didn’t want to screw it up. But I’d always thought I would eventually get a chance to tell him how much admiration I have for him, how his career is a testament to the triumph of personality over slick modernization.

I never wanted to explain that I meant no disrespect portraying him as a man whose head was attached to Godzilla’s body, since that could have been seen as a jab at him, you know, the “old dinosaur” of comics. I was responding to the portrait of himself he’d etched in his article in the NY Times, in which he described a world that had left him, at age 56, seemingly condemned to obsolescence. It seemed traumatic but I thought he fought back with resourcefulness, self-reflection and bravery, and I always wanted to tell him. But I thought there’d be time later. Clearly Herb had many, many good years left in him.

Man, I’m so consumed with loss right now. I’ve been sad all week. I never met him, but I feel like I’ve lost a friend”.

Josh Bayer, April 18, 2015

In the Hollow with Michele Nitri

This is my English translation of an article by Matteo Stefanelli already published on the Italian website Fumettologica. Thanks to the author for his kind permission.

After a couple of years in the business, the indie label Hollow Press is emerging as one of the few – but certainly one of the most interesting – small presses strongly dedicated to alternative comics. And yes, “alternative” is the right word, and not a vague and blurry category used in opposition to popular or serial. Or at any rate not entirely.

The whole peculiar world of the small publisher is in the name (let’s face it, rather unpronounceable) of its biannual magazine: U.D.W.F.G. is for underdarkweirdfantasygrounds, in other words a very radical vision of a darker and alienating fantasy. In a world where underground comics and – in general – underground cultural production seem almost dead, absorbed in large part by a publishing industry more open but also more opportunistically addressed to niches of “long tail”, it’s a rare and paradoxically refreshing experience to delve into disturbing territories. And so we can remember that, on the marginal edge of the “independent graphic novel” now led by a predictable marketing-oriented logic, creative forces continue to boil.

The first artists published by Hollow Press were Ratigher, Paolo Massagli, Miguel Angel Martin, Tetsunori Tawaraya and Mat Brinkman, cartoonists who know the score about dark fantasy and underground comics. But the true surprise has been Industrial Revolution and World War by Japanese artist Shintaro Kago, one of the most creative mangaka in recent years. Among the new projects, there is also a big news for Italian readers: Paolo Bacilieri, the eclectic author of Sweet Salgari, Fun and of several inventive single-run episodes for Bonelli Editore series, will publish a never-before-seen work with Hollow Press in 2016.

The brand founded by the young Michele Nitri, born in Foggia 26 years ago, is one of the publishing houses to watch. And now it’s reasonable to expect some surprises, because the identity he is building for Hollow Press is interesting not only in terms of content, but also for the model of (micro) business. In addition to printing books and a magazine, Nitri produces bizarre artoys (or action figures) designed by the same comic artists, as Ratigher or Mat Brinkman, and sculpted by one of the biggest European talents in the field, Marco Navas. Furthermore, he is selling directly the original drawings of many of the comics he publishes. In his own small way, Nitri seems to embody the perfect example of those small publishers who perform their mission with a free and modern approach, focusing on the books but not forgetting other areas of the culture industry, showing the versatility of the artistic personalities – and of their audience.

We’ve asked Michele Nitri some questions about Hollow Press’ new projects and future goals.

How was this first and a half year of activity?

I don’t have a word to recap the whole story. We started badly, went on well and “finished” very well. As usual, when I decide to do something, I put myself to the test, like in a videogame: there are people who insert the disc and select the easy mode, others who want to enjoy a normal experience and then there is someone – like me – who is out of his mind and always chooses the HARDCORE mode. To put it simply, when I decided to start Hollow Press, I made a lot of questionable decisions: 1) I created a crazy email address, while usually the simpler is the better; 2) I invested 8000 euros without any editorial experience; 3) I focused mainly on a magazine – a format essentially dead – with an unpronounceable name, in English, underground, and expensive (18 euros).

With the first two issues of U.D.W.F.G. I always managed to break even within 6 months to invest in the next issue (paying everything in advance). In late February of this year I decided to register for VAT and to become a real publisher, printing a book entirely dedicated to Shintaro Kago and a 400-page “best of” Tetsunori Tawaraya, catching up with the only pre-orders (two weeks) the money to pay IN ADVANCE the typography, the graphic, the authors and so on. So, after so much effort and self-taught “study”, I can say: very well!

Did you find your market, then?

You are right to say “your” market, because I’m not seeing something similar around. My market is and will definitely remain smaller than many others. But in its own small way it works, and it’s always satisfying when you create something that works. The core idea of my market is about signing an alliance between “undergrounders” from all around the world. And since it’s a fringe genre, most of the fans speak a bit of English … so why don’t make books in English for everyone? If the underground in Italy is doomed to die, it means that it doesn’t have enough readers to survive with dignity. It makes no sense to print only 500 copies of a book to sell 50 or 100; instead it makes sense to print a book of 500 copies and sell 150 copies in Italy, 150 in the US, 150 in Europe and 50 in other countries in maximum one year, all direct sales!

Do you think to carry on with direct sales, through the website and the festivals, or you’re planning to use the channels of traditional distribution? Did you have an agreement with the authors about direct sales?

Only direct and, when it happens, we’re taking part in the most important festivals. I say this because last year I experienced smaller festival and they aren’t worth the hassle. If in Lucca’s Self Area, in a marginal zone of the show, with books in English and difficult to sell, I managed to sell more than three times than in other well-known festivals that should be more appropriate to my publications, we can take stock of the situation and move on…

As for the distribution, I think it would be very difficult to survive through it: considering the promotion, I would have a 30% of the cover price, and with that money you can’t pay anyone. The distribution is for the strong ones, is for the big publishers who have the strength to make it work, but it wouldn’t be good for me. The small publishers trying to sell through distribution often delude themselves and then die.

At the bottom of the Hollow Press there is a fan who has always been interested in alternative stuff, and who was always looking for cool and hidden products… And now I want customers like me. I don’t want to attract occasional buyers: my clientele has to be loyal, so that they can trust me, but above all I can trust THEM. And I’ll do everything possible to don’t ever disappoint their expectations.

How important is the foreign audience for your books, original drawings and artoys?

Italian buyers are about 30%, the remaining 70% is foreign people and the most of them are from the United States or Canada. Then there is the fact that working with all the countries is anti-crisis, or almost.

Selling original artworks is for Hollow Press a way to support the printed production, or a goal in itself?

Both things. With the advance purchase of the original artworks I can pay the artists fairly: I can assure you, with a story of 10-20 pages for me, they earn the same money they would earn with a small/medium publisher with a book of 100-120 pages (a year of work), with the only clause of losing all or most of the originals. After all we’ve to think up something to make things work…

Then there is another reason. I “am born'” as a reader and a collector of original pages. The market is fertile and ever-expanding, so why don’t take advantage of this? Obviously it isn’t easy. I’m collecting comic arts since I was 18 years old, I’m “studying” this field by many years, and I can say that maybe I still don’t know all the tricks to get it going at the most. It is a complex thing, and you’ll never stop learning. I have to offer fair prices, without looking for the big deal, but searching for honest transactions, so that the purchasers will come back to me time after time.

What projects are you working on at the moment?

I’ll only tell the ones I’m sure of: the upcoming third issue of U.D.W.F.G. – it has been slightly delayed due to overwhelming commitments of a couple of artists. The next special book dedicated to young British talent James Harvey… and another special book due out by next year, this time from the great Paolo Bacilieri. And then a lot of other projects I prefer not to disclose at the moment. Despite I have big names in store, the space is little, many people are contacting me, and I’m doing my best to take the right choices … Ok, I’m telling you this other: I’m trying to publish Mat Brinkman’s masterpieces. It isn’t easy but if I’ll manage to do this, you’ll never thank me enough (laughs). Seriously, any connoisseur of underground comics knows that Brinkman is the most influential artist of the last two decades.

Do you think we are in a good moment or in a difficult time for the small press scene?

Bah! Everyone is complaining but no one is doing anything to change the situation. Many blame the publishers (I don’t mean everyone but a lot of people) and this is fair, but the real question is: are you playing at the cartoonist? Or are you a real cartoonist?

However, I’m enjoying so much watching new projects as Ratigher’s “Prima o Mai”. Apart from the numbers, it’s the message that perhaps unknowingly he launched that matters: the publisher shouldn’t be always seen as an arrival point, but we have to launch collaborations between artists and publishers. We have to grow together and – even if it could seem utopian – share the profits.

What does publishing underground comics means to you? Do you think there is still something we can call “underground” out there?

That’s a frightful question for everyone… But from my point of view I don’t care. The underground is “what CONTEXTUALIZED by CONTENTS goes against the mainstream”. Now it’s a worn-out word, someone uses it because he’s from the squats, someone for promotion. But it’s all about the contents…

Crumb is underground because it WAS underground for his time. Objectively, now it’s like an excellent satire. Kriminal and Satanik were underground because they couldn’t be exposed in the newsstands. Miguel Angel Martin and Mike Diana are underground because they were on trial for obscene contents. The comics I’m publishing are underground because they tell fantasy stories, but a reader of “normal” fantasy tales can describe them as a macabre or weird horror, because it’s a new kind of fantasy, without elves, dwarves, gnomes and so on.

One day, “underground” will be so much a cliché that “artistic” and “alternative” comics will become “commercial”, while Italian comics as Tex or Dylan Dog will be “underground”! The comics will be taken too seriously, and a lot of people will miss the lightness of comics of the past and they will search for them to live again those good old times.

An interesting thing is that authors like Ratigher or Bacilieri, to make two Italian examples, work also with publishers that have nothing to do with the underground in the matter of distribution as for imagination. Why are you still using this label, then?

In fact I think these authors aren’t underground. In my opinion Ratigher made always art comics, very weird, beautiful, but – although multi-level – accessible to all. The same is for Paolo Bacilieri. Maybe I would call underground only his Zeno Porno. Now, inhumanly, he still manages to find time to develop his authorial vein publishing nearly a book a year, but he can be roughly defined more “commercial” because he works for Bonelli.

This doesn’t absolutely preclude any collaboration with Hollow Press: I don’t use the word “underground” as a rigid category because I would be arrogant, communicating a kind of stupid and exclusive feeling of superiority.

I still use this word because I feel I can do it with the kind of products I’m publishing. For example, I’m always seeing new comics or magazines about extreme sex: well, unlike the appearances, that isn’t underground, it has already been done or said twenty years ago, now it doesn’t tell anything. After Miguel Angel Martin, Mike Diana, Trevor Brown and others, there’s nothing to tell about it. While I would like to point out that the same Martin, with his The Emanation Machine in U.D.W.F.G., has included his extreme sexual themes of alien characters in a fantasy context… And yes, this is original!

I’m telling it again, anyone can potentially collaborate with Hollow Press, because we have our roots in the “dark weird fantasy” – of which Mat Brinkman is definitely the pioneer – and this is a genre where there is still so much to say. No matter whether you’re mainstream, good for a graphic novel or for an extreme magazine, because it’s important what you can produce: underground is in the contents, not in the curriculum.

If I can, I’d like to conclude this interview with a true anecdote.

(my mother’s friend): “I heard your son is now a publisher besides a detergent seller…”

(my mother): “Yes, he’s a fan of underground comics since forever…”

(my mother’s friend): “Ah… And what are they? Like Dylan Dog?”

(my mother): “Don’t ask me, he showed me the first book he published for a whole day, he helped me to read it, but I still don’t understand what it is.”

(my mother’s friend): “Ah… Ok”.

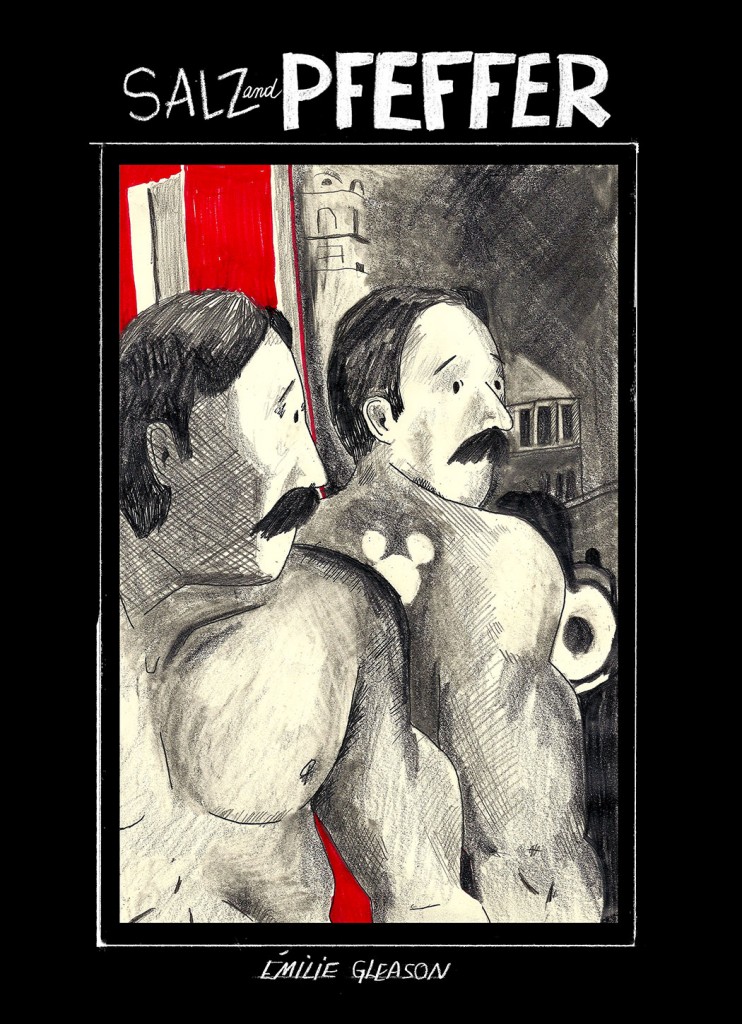

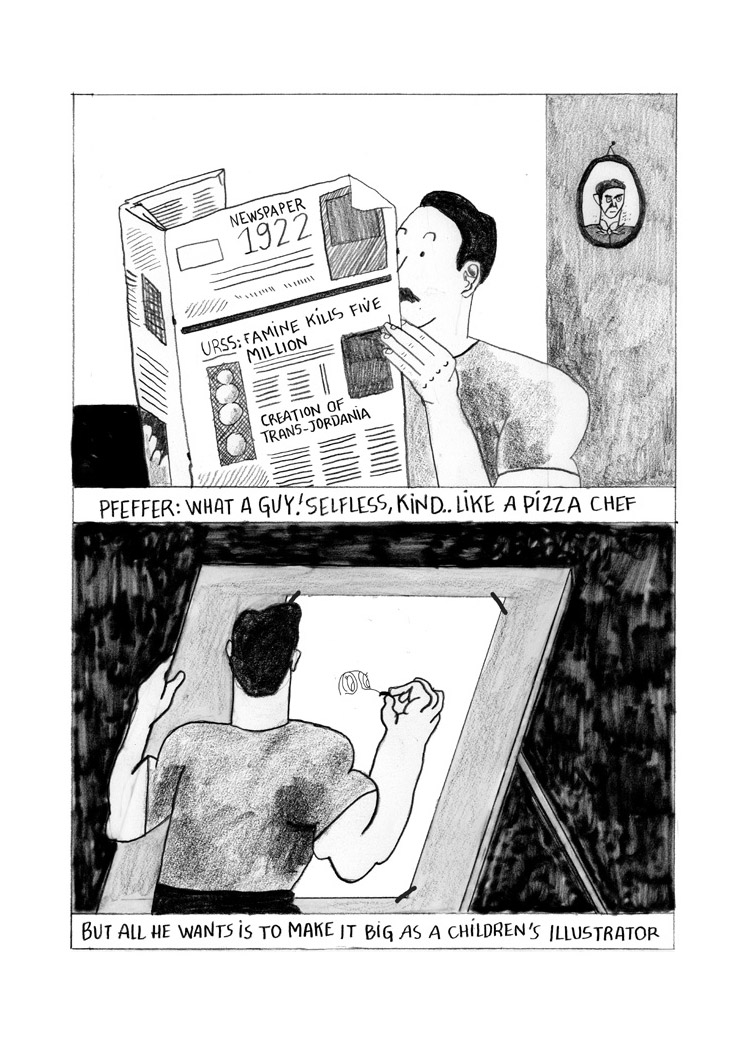

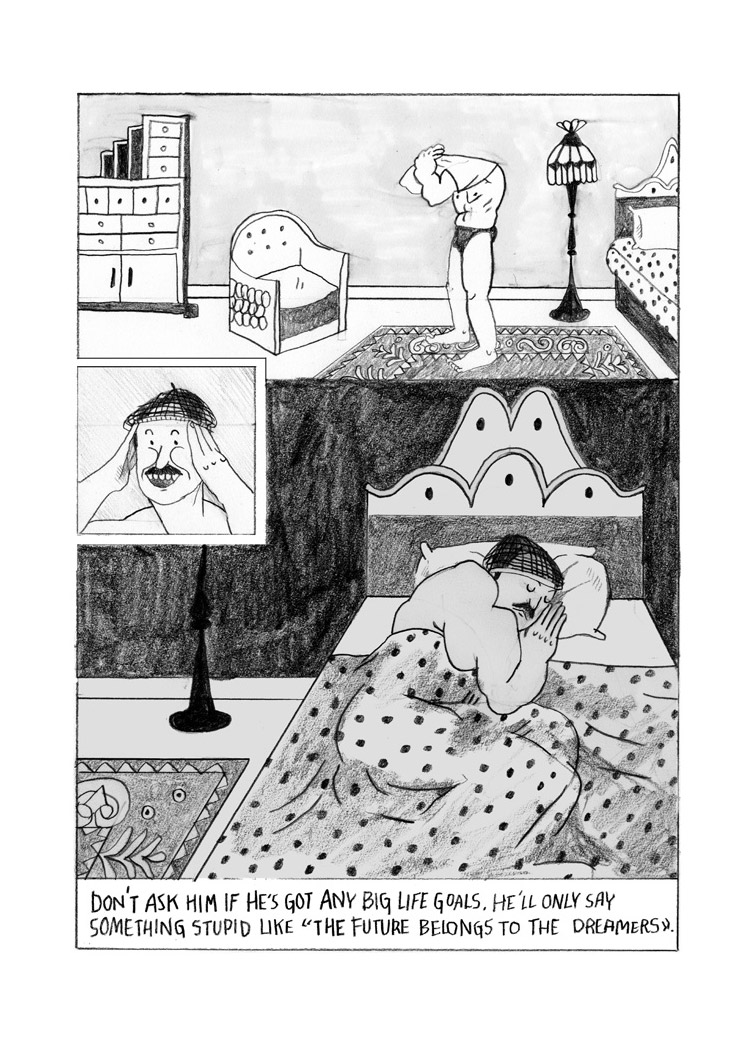

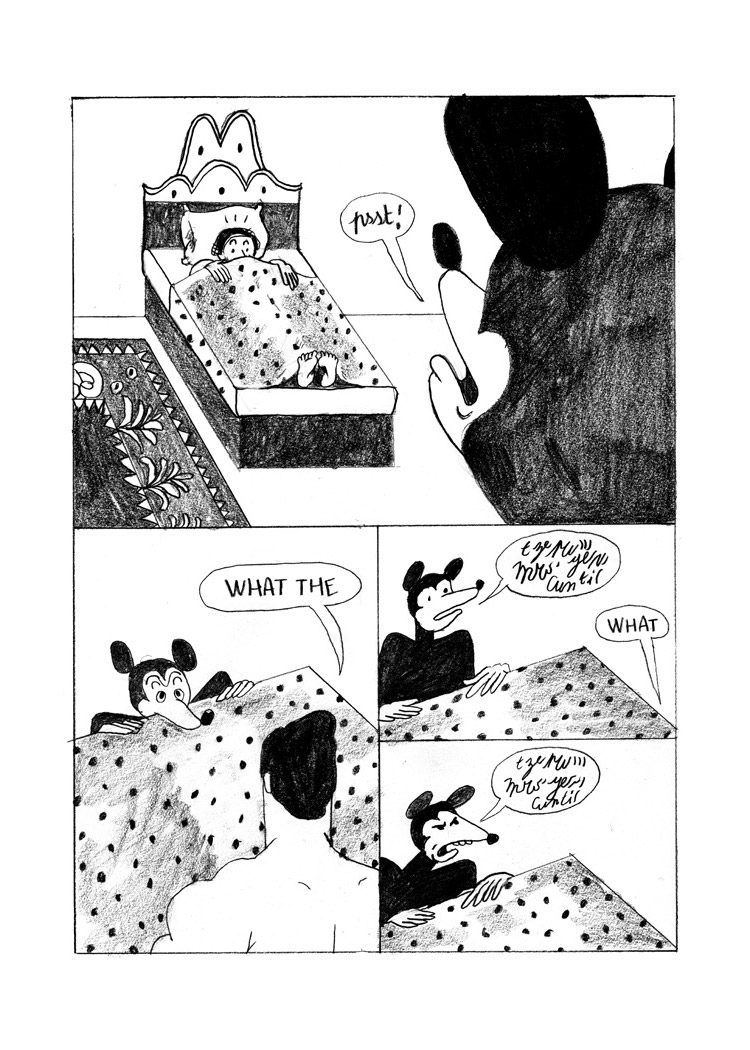

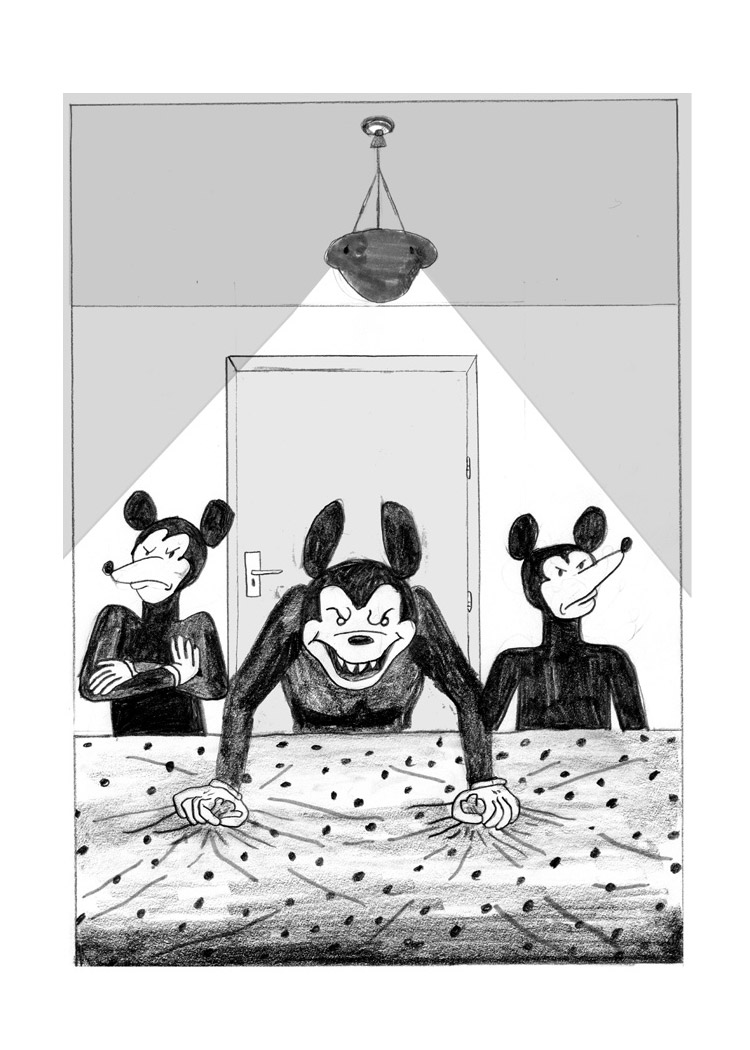

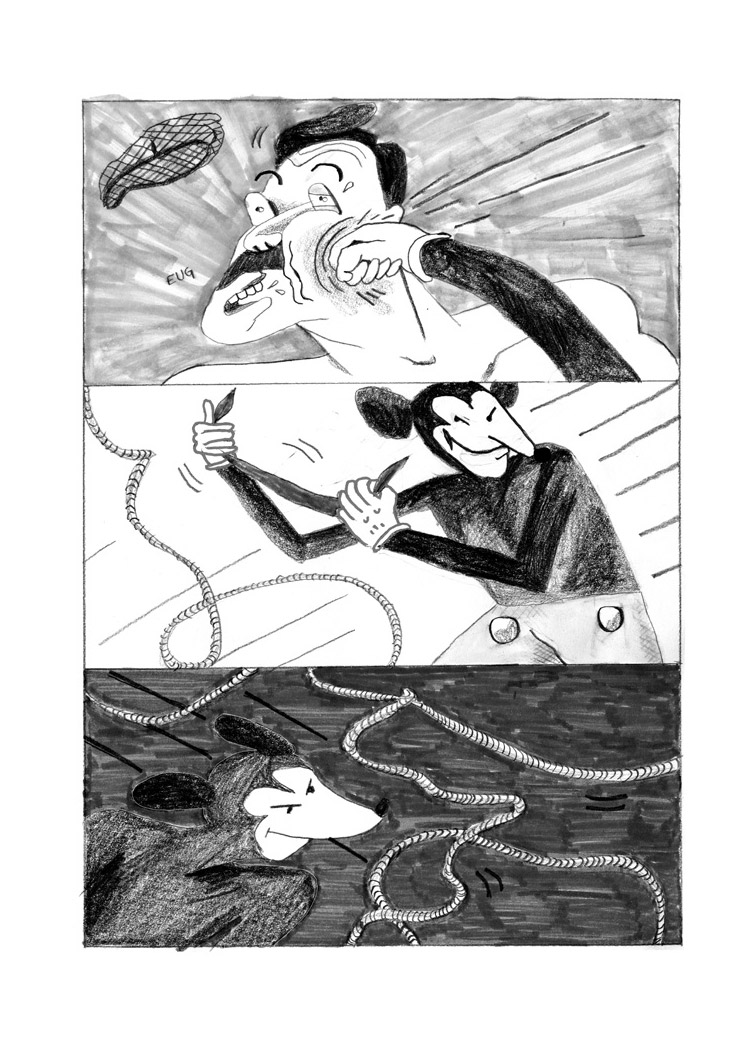

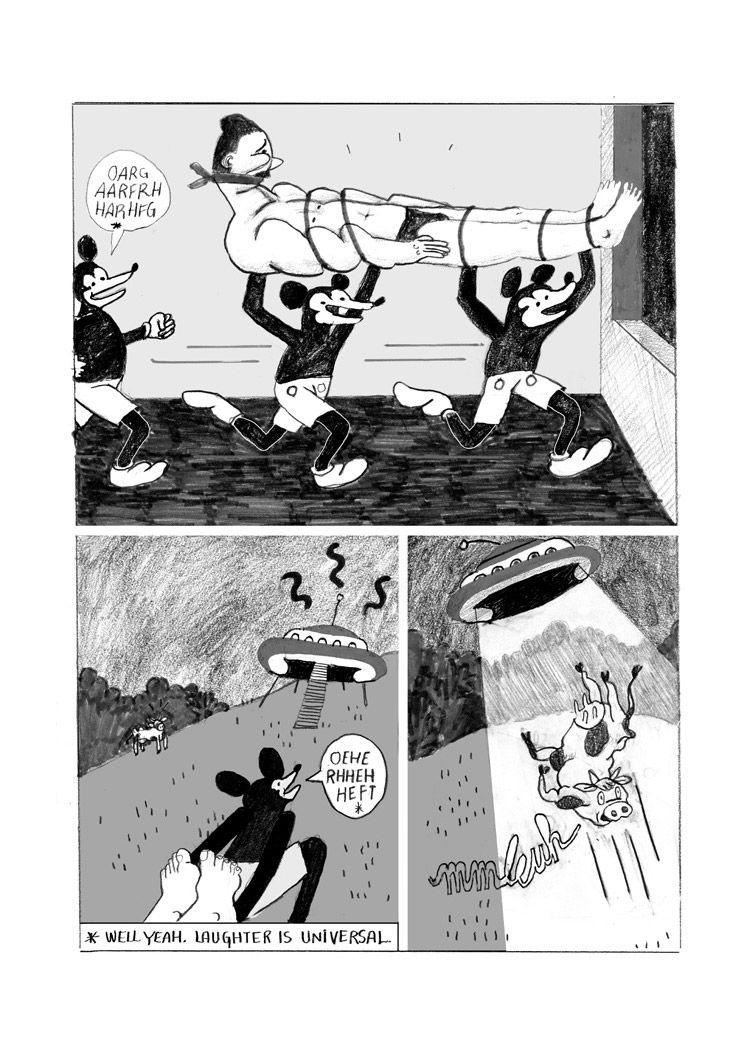

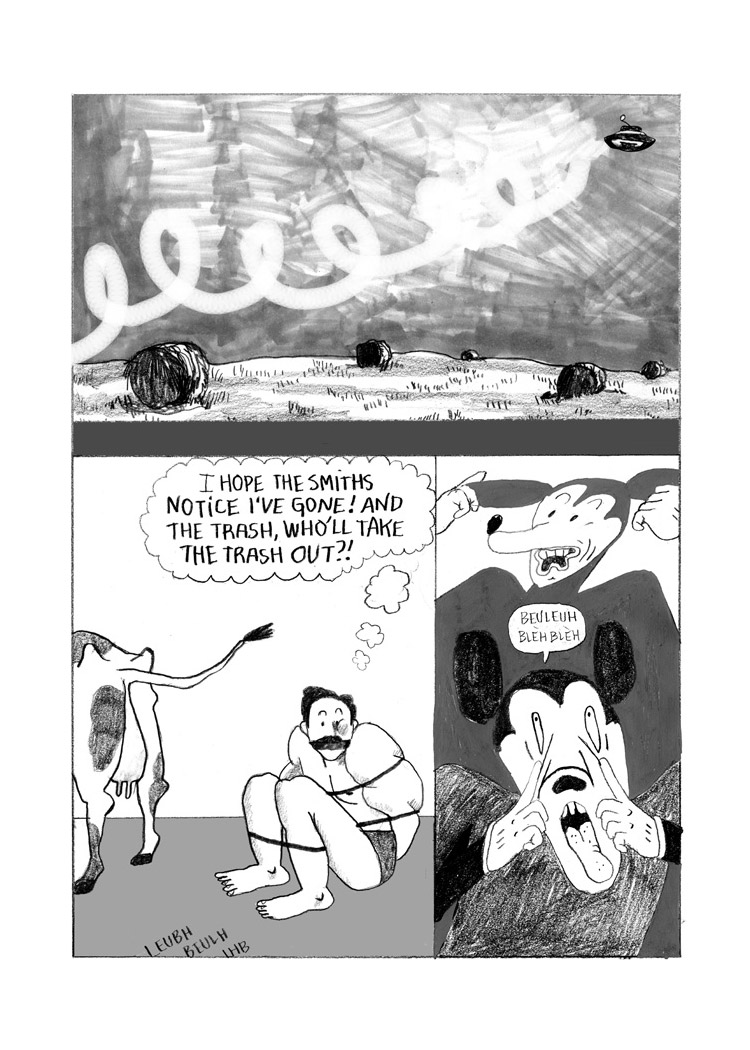

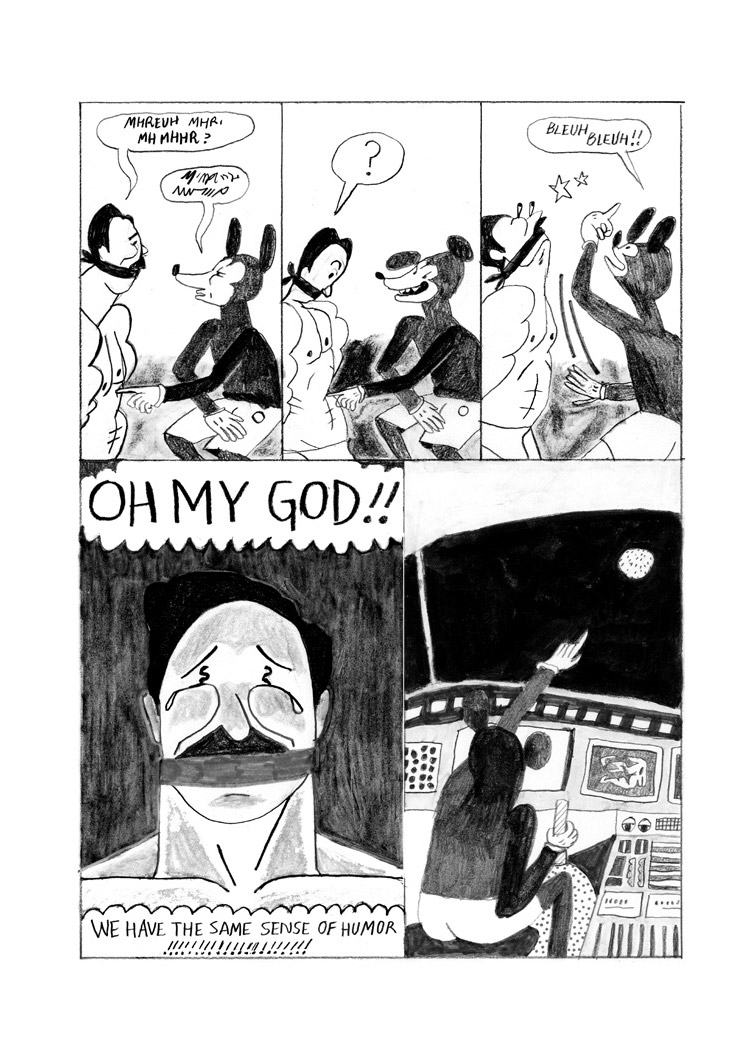

“Salz and Pfeffer” by Émilie Gleason, a preview

Born in Mexico, Émilie Gleason grew up in Belgium, lives in France and last weekend was in Canada, where she attended Toronto Comic Arts Festival for the debut of Salz and Pfeffer, her first book for the American market, published by 2D Cloud. Pfeffer is a tidy and respectable man who dreams of becoming a children’s illustrator. A night he is abducted by three aliens looking as evil brothers of Mickey Mouse. Salz and Pfeffer is a funny comic, drawn with an old-fashioned pencil style and with a strong sense of dynamism. Gleason’s work could seem a cartoonish version of C.F. and Gabriel Corbera’s comics and this amusing 76-page trip is violent, ironic, surreal and definitely worth your attention, as Émilie’s other comics, available at her online shop. Below the first pages of the book.

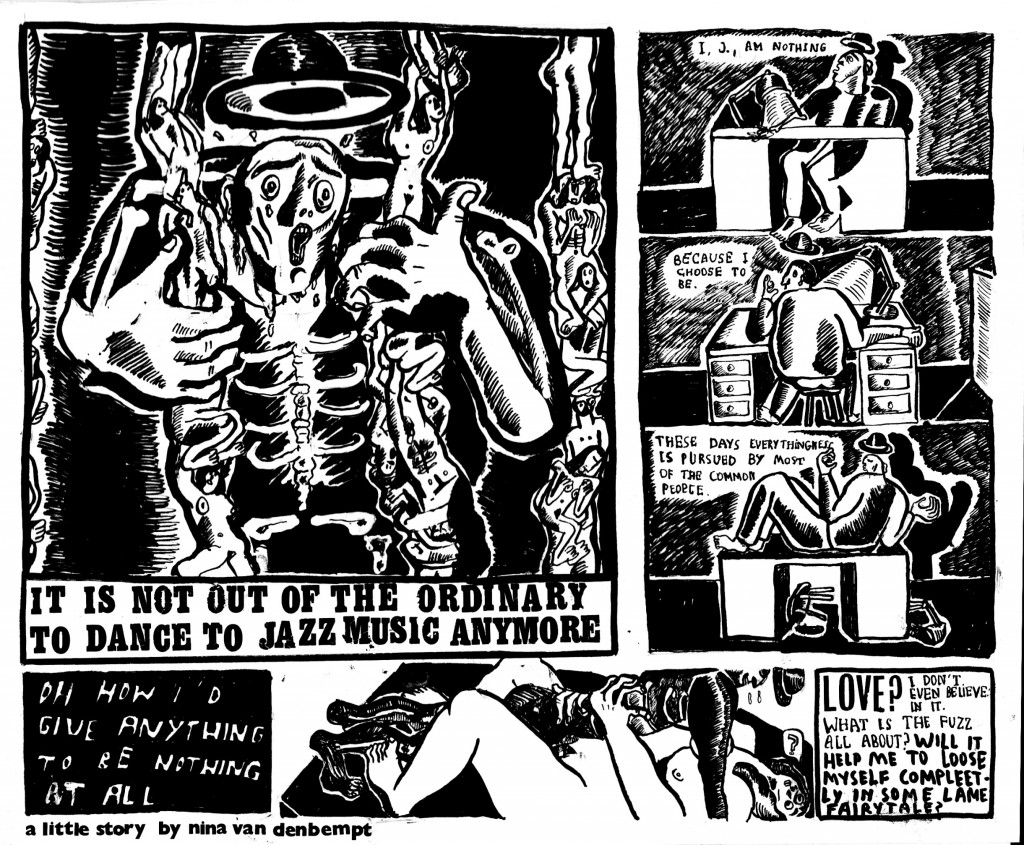

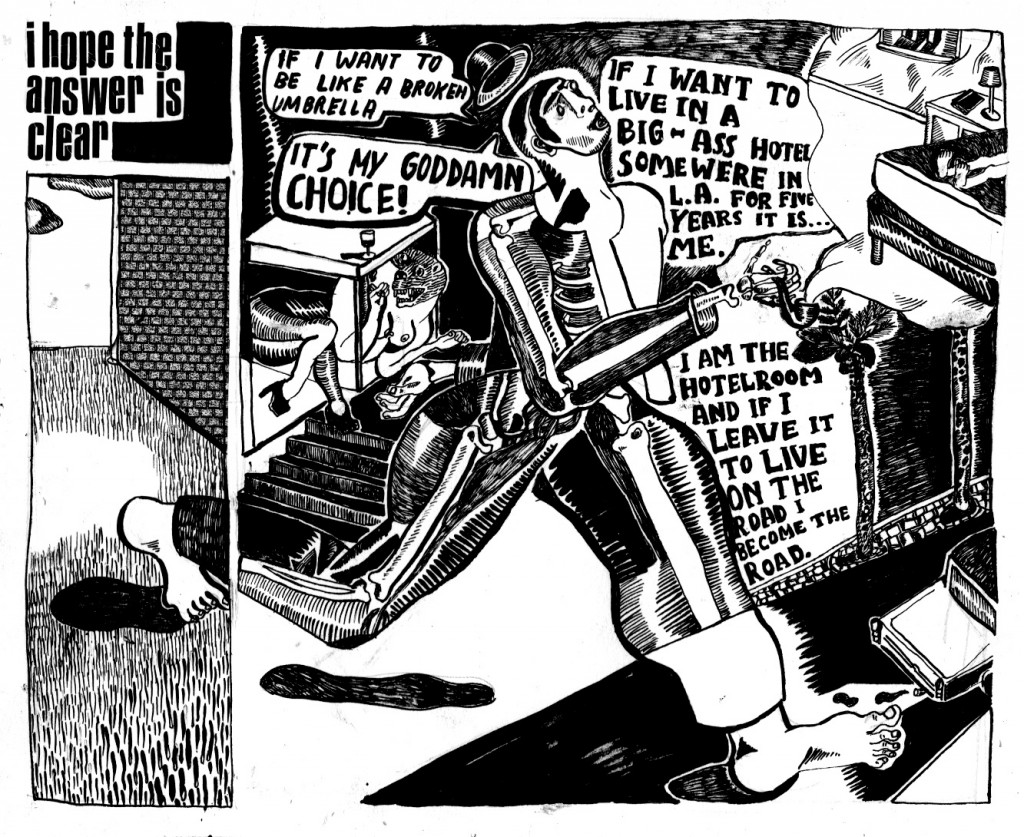

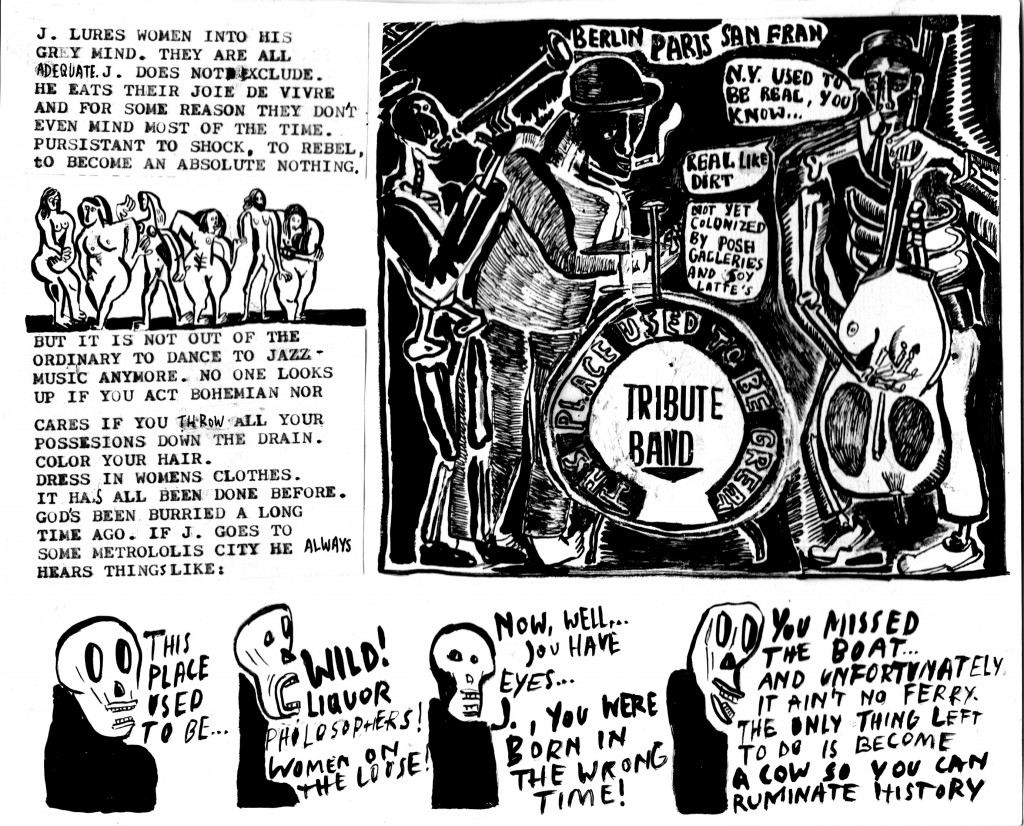

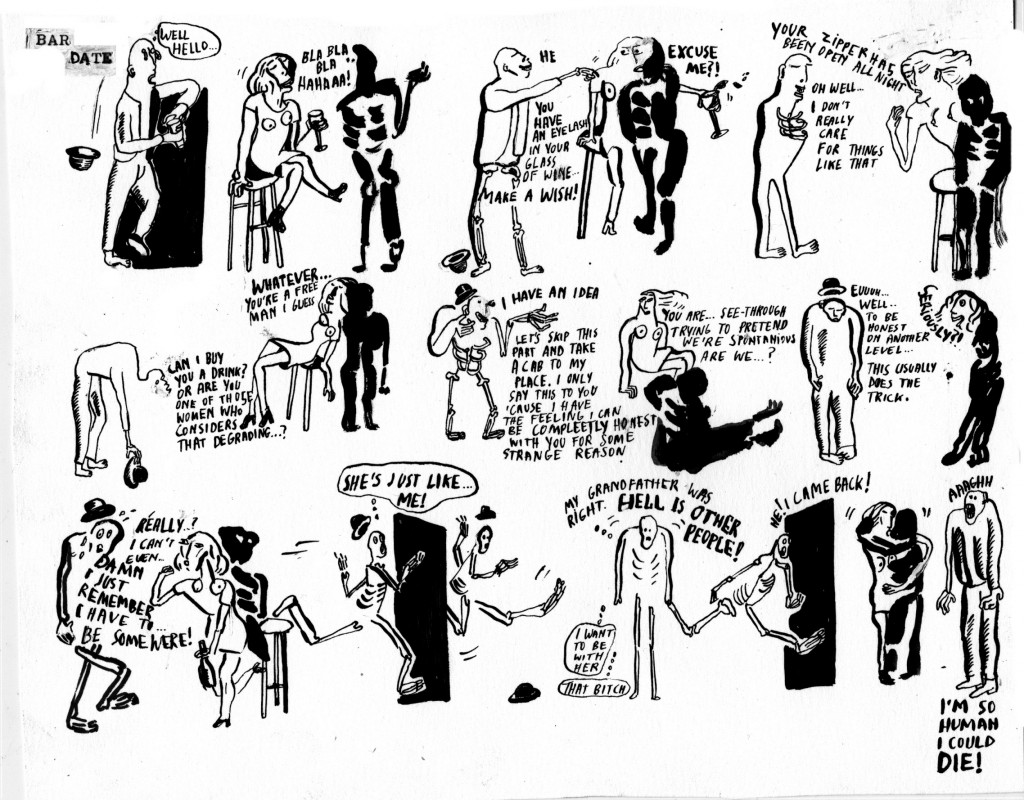

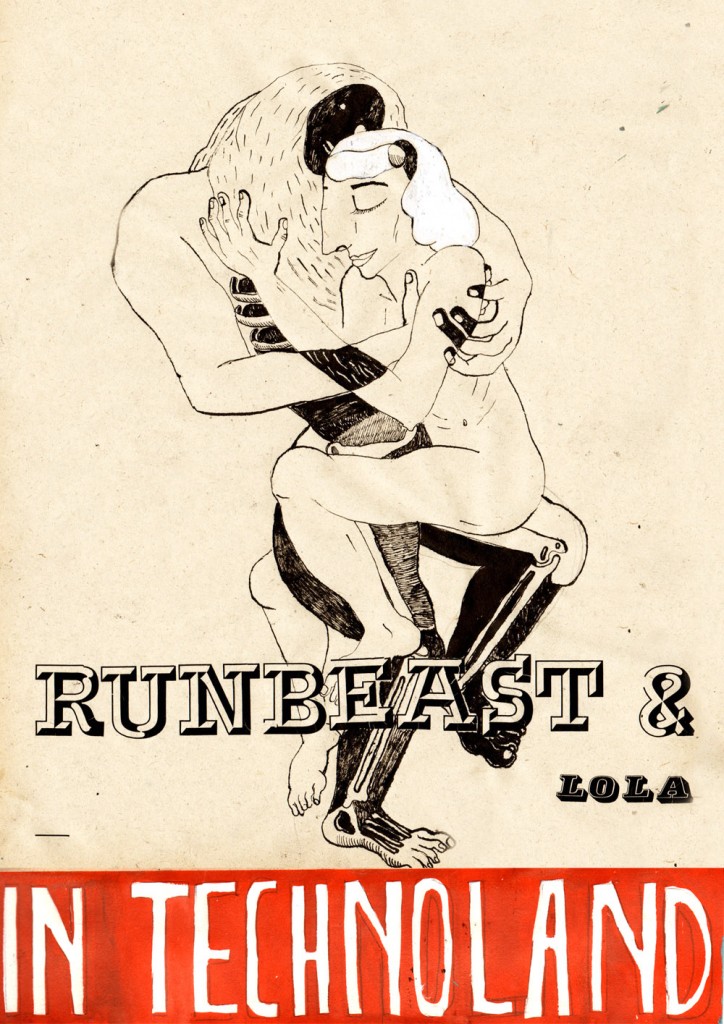

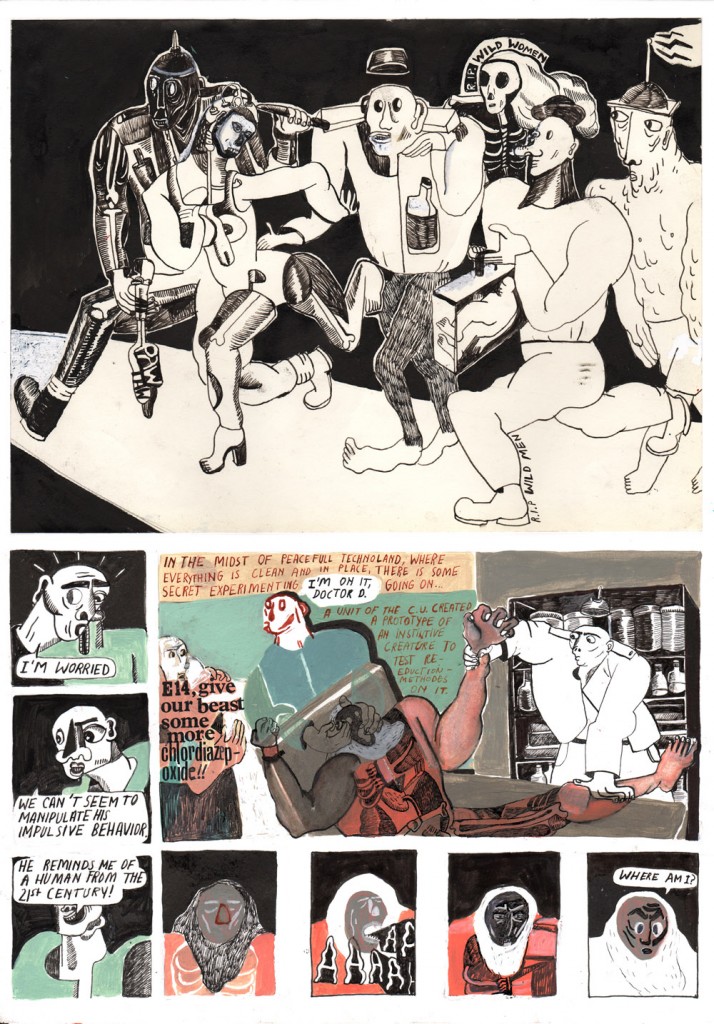

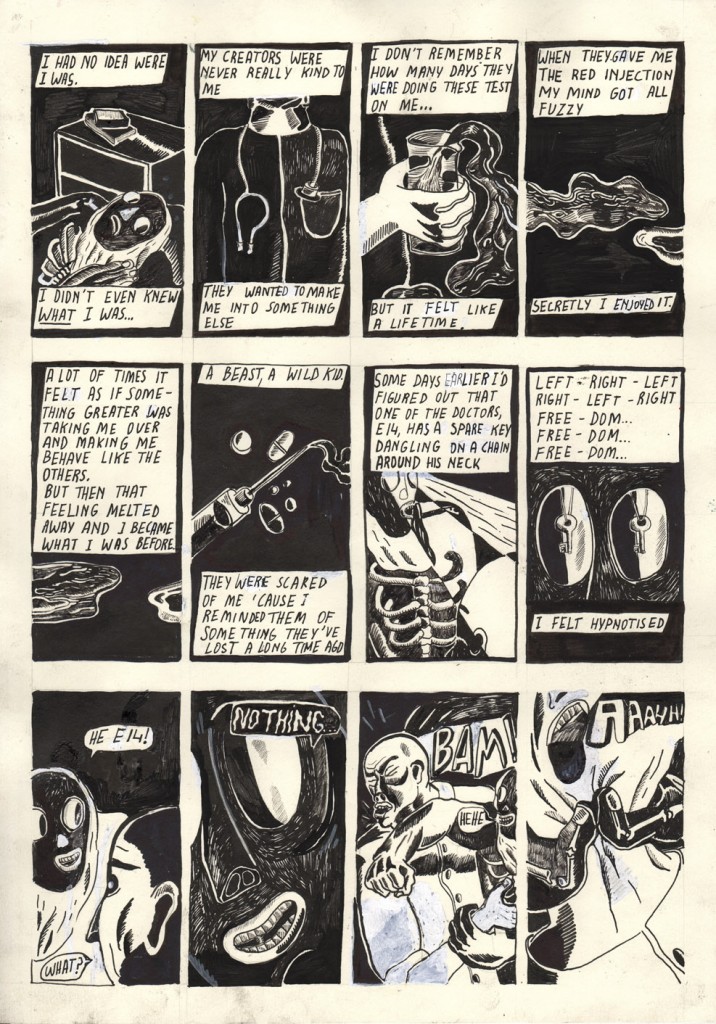

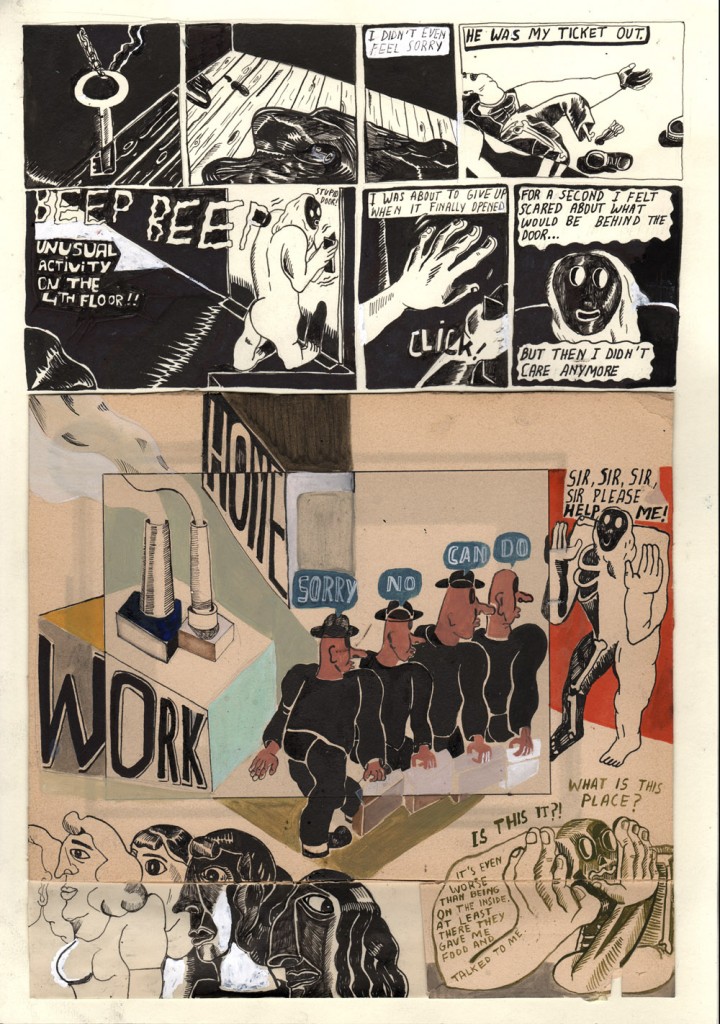

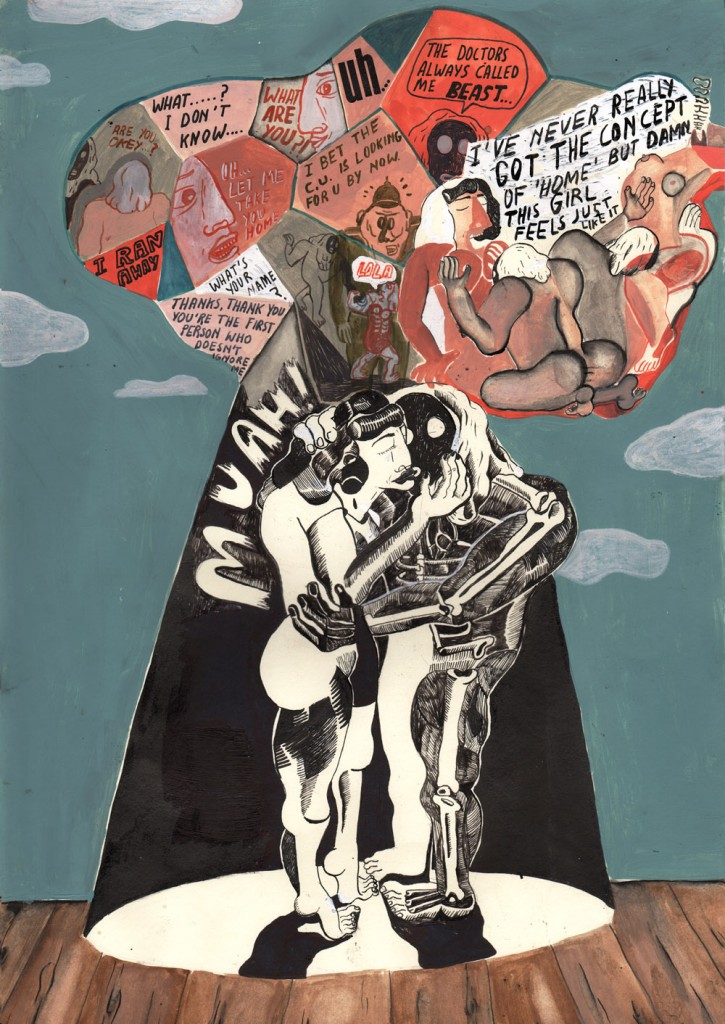

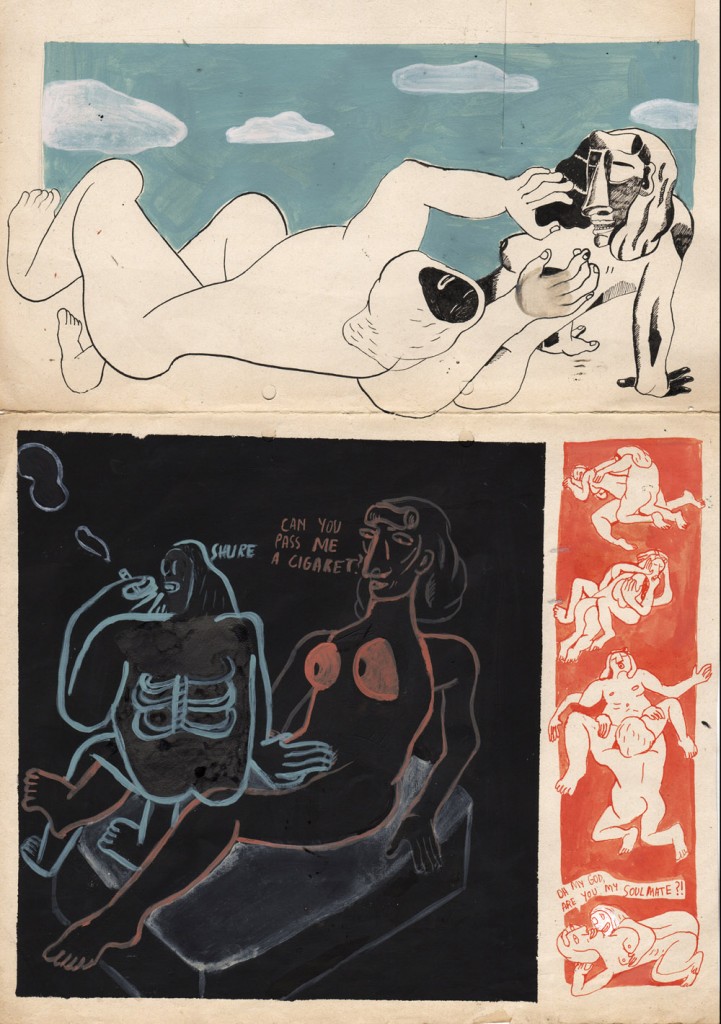

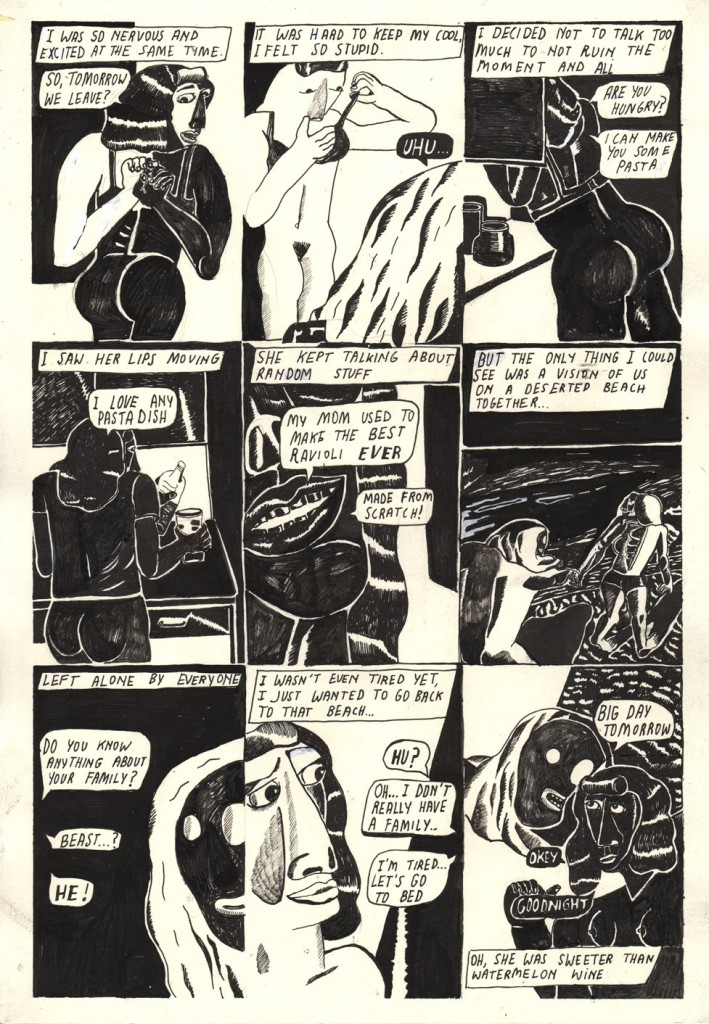

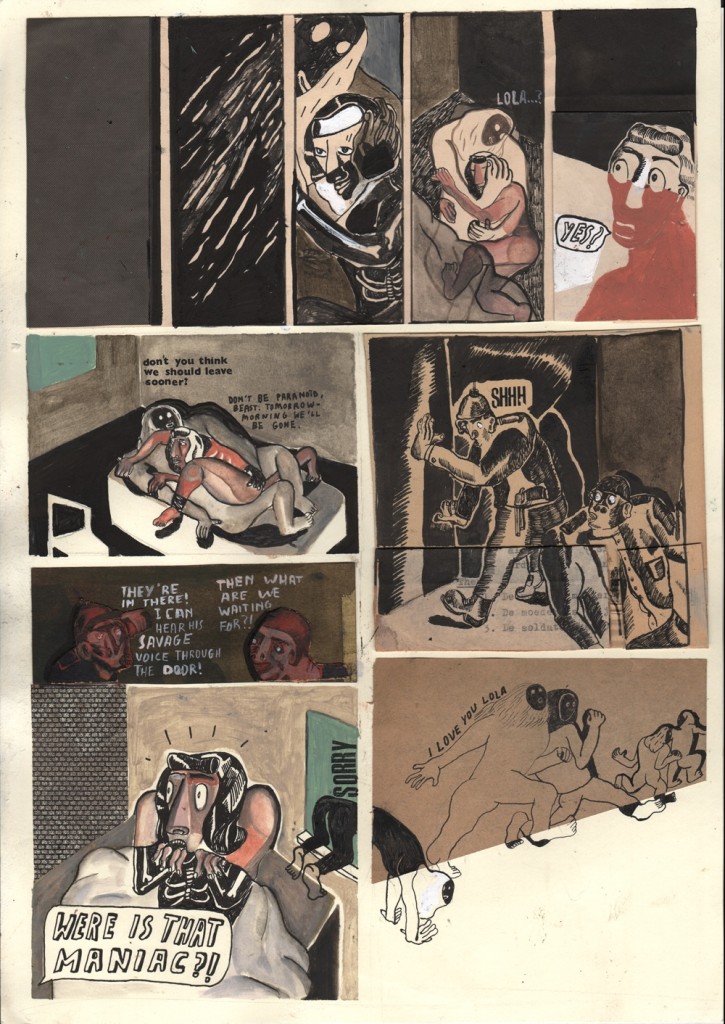

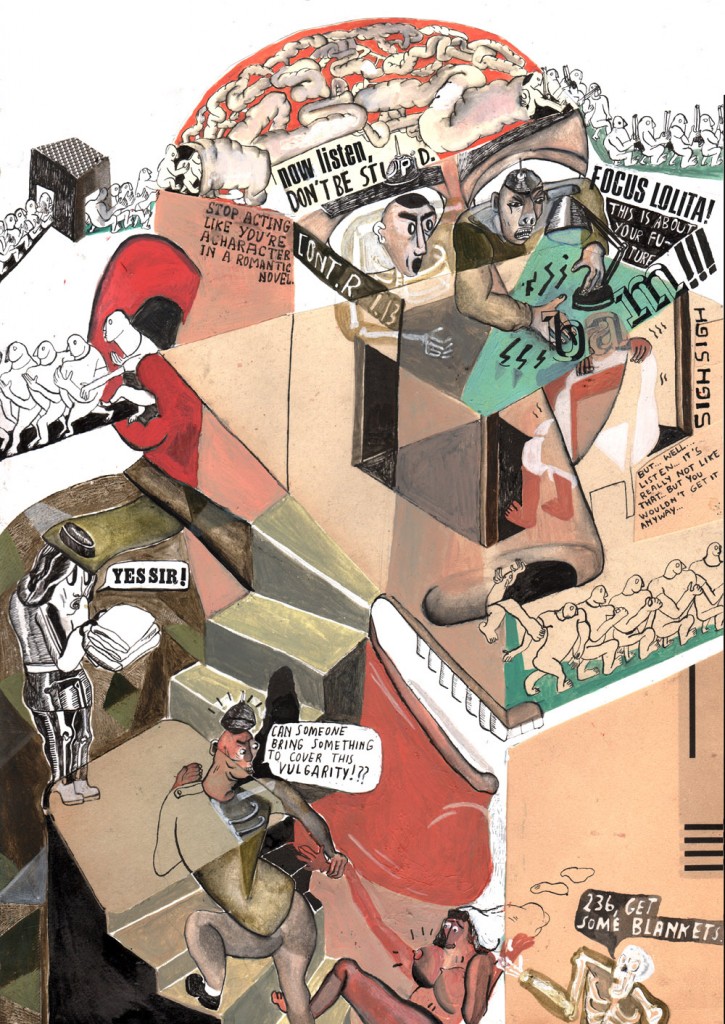

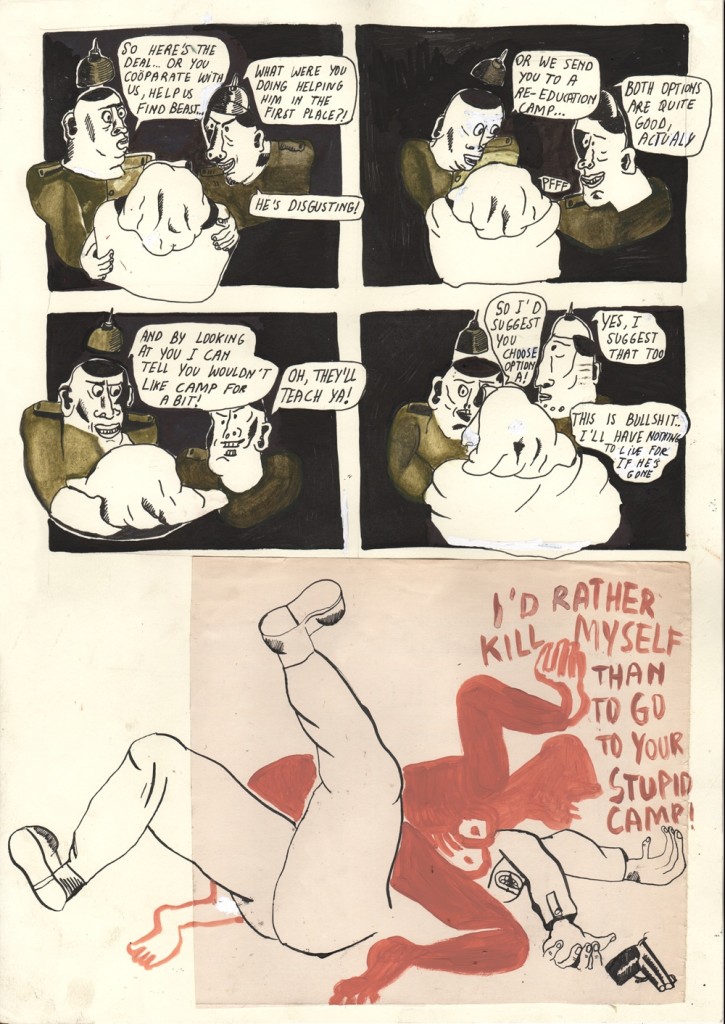

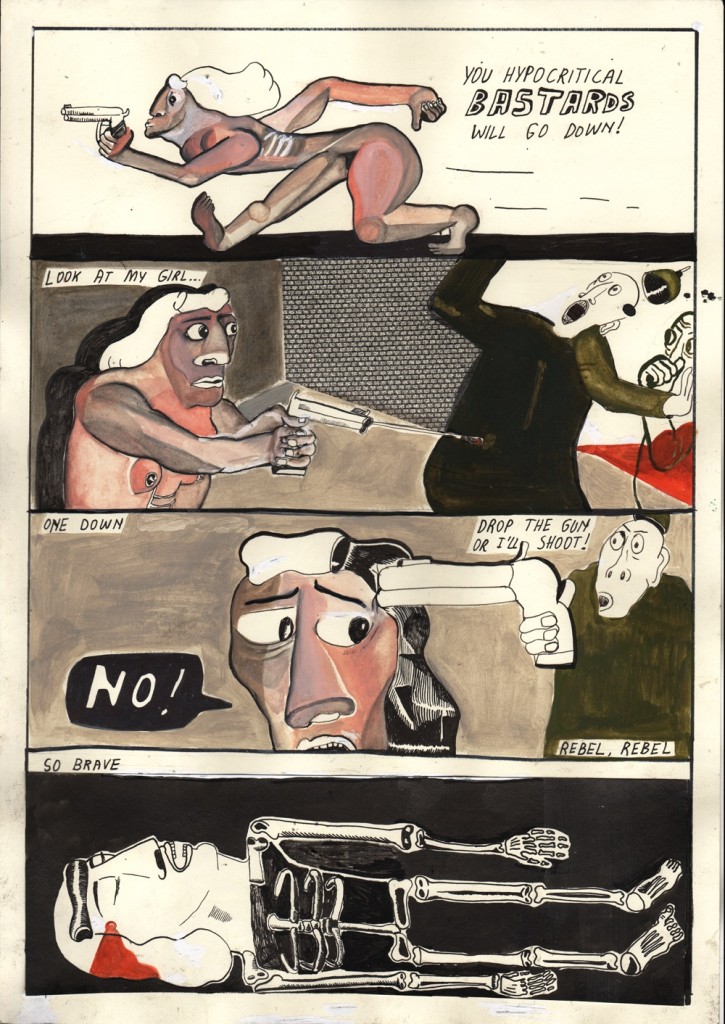

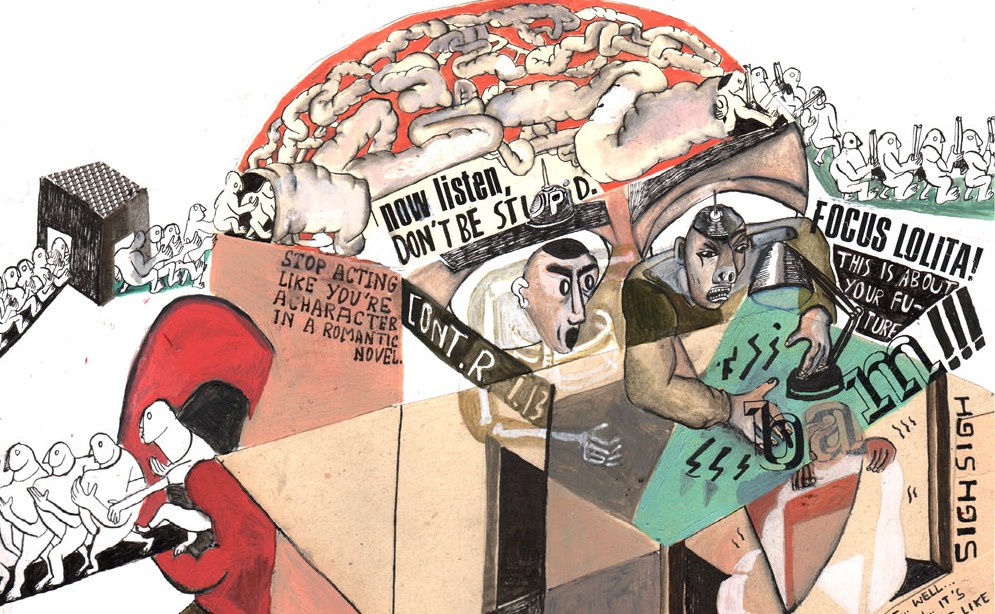

Two comics by Nina Van Denbempt

Nina Van Denbempt is a Belgian artist born in 1989 and graduated in illustration in Ghent, a beautiful city in Flanders where also talents as Brecht Evens and Brecht Vandenbroucke grew up. She founded Tieten Met Haar collective with other girls from Sint-Lucas School of Arts and it’s in the fourth issue of their anthology that I first encountered her work, where deformed bodies, irregular lettering and the juxtaposition of different techniques give life to unconventional pages, as you can see in the comics I’m posting below. The first one is It is not out of the ordinary to dance to jazz music anymore, a four-page story published in the Tieten Met Haar anthology and in the Captain Foggy Brain zine, distinguished by a well-balanced mix of lyricism and irony. The banality of everyday life and of its rituals seems one of the main subjects of Nina’s work and it’s also a key theme in the second feature, Runbeast & Lola in Technoland, a more structured tale set in a future repressive regime, with an original use of color. Nina is actually working on her first full-length comic, Barbarians, a travel-love-action story that takes place in an apocalyptic Europe.