Everything is ending “Here”

“Di tanto in tanto arriva un artista che prende il potenziale accumulato dalla sua disciplina e lo rielabora in nuovi modi di vedere e sentire. Cézanne ci è riuscito nella pittura, Stravinskij nella musica, Joyce nella scrittura – e penso che Richard McGuire lo abbia fatto con i fumetti”.

“Di tanto in tanto arriva un artista che prende il potenziale accumulato dalla sua disciplina e lo rielabora in nuovi modi di vedere e sentire. Cézanne ci è riuscito nella pittura, Stravinskij nella musica, Joyce nella scrittura – e penso che Richard McGuire lo abbia fatto con i fumetti”.

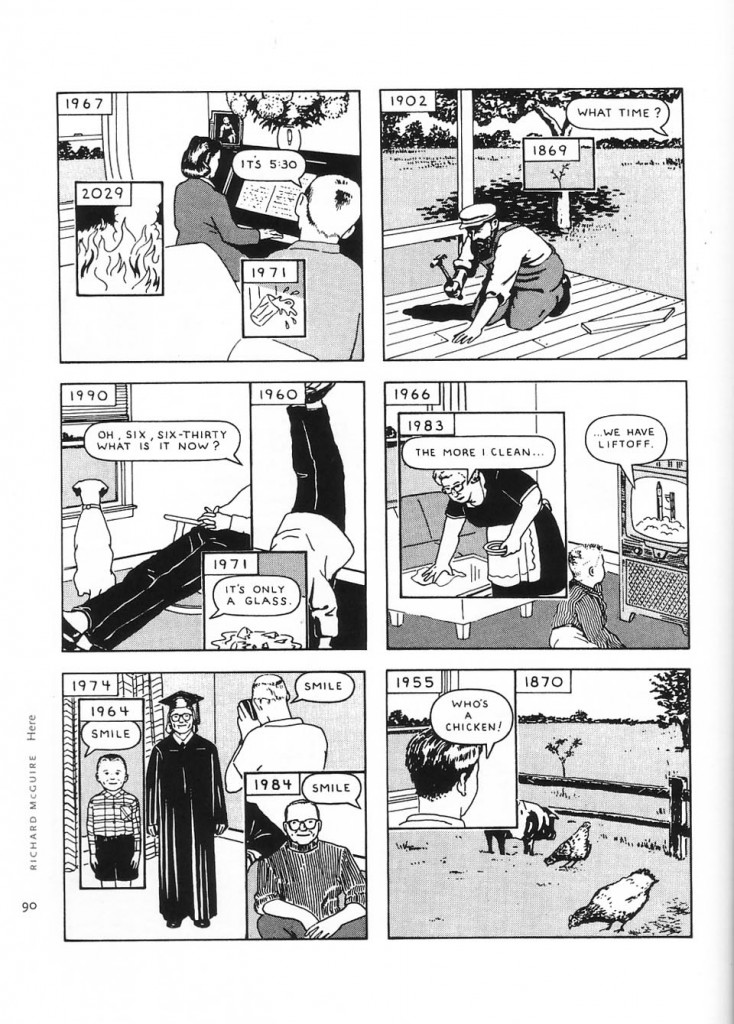

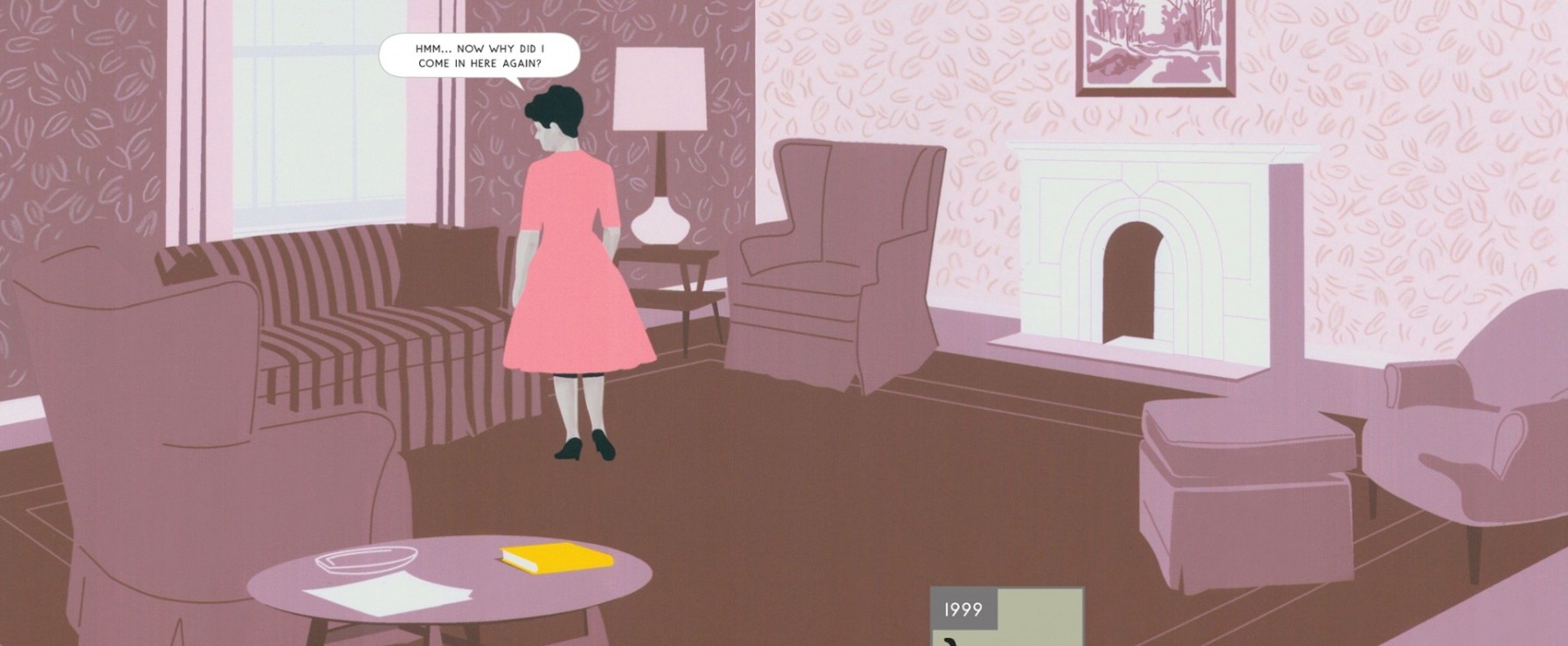

Basterebbe questa frase di Chris Ware per capire l’importanza della prima incarnazione di Here di Richard McGuire, una storia di 6 pagine apparsa nel 1989 in Raw vol. 2 #1 e che è possibile leggere qui. Era quello il famoso fumetto – rivoluzionario, stracitato, oggetto di saggi, convegni e persino di un cortometraggio – in cui l’artista statunitense – copertinista del New Yorker, bassista della band Liquid Liquid, autore di libri per bambini e film d’animazione, grafico e altro ancora – raccontava con un approccio estetico essenziale la storia di un angolo di mondo in diversi momenti storici, definiti di volta in volta da una data. Ma la caratteristica principale di Here erano le finestre che apparivano e si affastellavano creando il caos nelle sei ordinate vignette di ogni pagina, dando vita a passaggi temporali repentini che portavano il lettore a spostarsi in meno di un batter d’occhio dalla preistoria al futuro, mostrandoci per lo più l’angolo di una stanza ma a volte anche cosa c’era e cosa ci sarà in quell’angolo, come uno scenario lavico nel 500.957.406-073 a.C., l’edificio ancora in costruzione nel 1902, pompieri che spengono un incendio nel 2029, una cerimonia all’aperto nel 2033.

“Avevo realizzato due strisce che erano state pubblicate poco prima di Here – ha raccontato McGuire in un’intervista a Thierry Smolderen pubblicata sull’ottavo numero di Comic Art del 2006, dove è stato ristampato anche il fumetto originale e dove è apparso il saggio di Ware citato in apertura – in un piccolo magazine chiamato Bad News, curato da Mark Newgarden e Paul Karasik. L’idea iniziale mi venne dall’appartamento in cui mi ero appena trasferito. Pensavo a chi aveva vissuto lì prima di me. Feci alcuni sketch di una pagina divisa in due parti verticali, dove sulla sinistra il tempo si muoveva avanti, mentre sulla destra si muoveva all’indietro. All’epoca, stavo frequentando delle lezioni tenute da Newgarden e Karasik sul fumetto (dopo una serie di conferenze di Spiegelman che avevo già seguito poco prima), e loro mi incoraggiarono ad andare oltre i semplici sketch per svilupparli in una storia. Un giorno ero in giro con un mio amico, Ken Claderia – con cui andavo a scuola e che adesso è uno scienziato che lavora per la Stanford University – e fu un suo commento che fece a proposito di Windows che mi portò a pensare che poteva trattarsi di una vista multipla piuttosto che di uno split screen. Fu quello il momento “eureka”. L’idea è basata su una concezione multi-dimensionale del tempo – nel pensare il tempo non come lineare, ma come se tutto il tempo esistesse simultaneamente. Volevo che lo spettatore pensasse all’immagine più ampia, al fatto che noi entriamo in contatto soltanto con una parte della realtà. I dinosauri stanno ancora camminando da qualche parte in questo spazio ma in un altro tempo”.

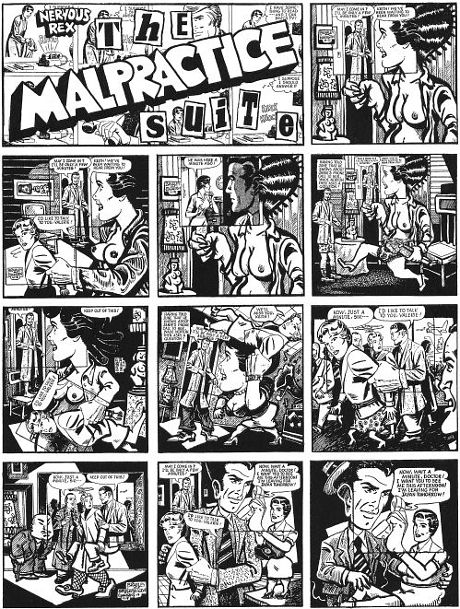

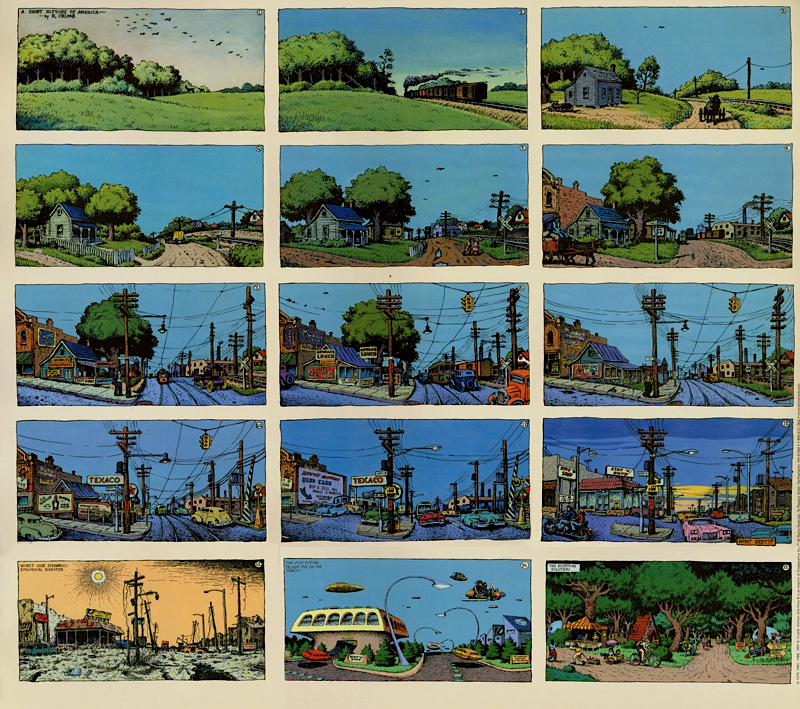

Da allora il fumetto di McGuire è stato paragonato a tante opere che hanno rivoluzionato la forma delle arti, ognuna ovviamente a suo modo. Ware lo paragona all’Ulisse di Joyce o anche a Fuoco pallido di Nabokov, citato per l’uso delle note a pié pagina, soluzione poi portata alle estreme conseguenze da David Foster Wallace. Matt Seneca in una bellissima recensione per The Comics Journal del nuovo Here utilizzava Il pasto nudo di William Burroughs e Viaggio nella luna di Méliès come opere altrettanto fondamentali per la loro ambizione formale. L’uso dello split screen nel cinema ha avuto sicuramente un ruolo importante nello sviluppo dell’idea iniziale di Here: esempi celebri sono Lo strangolatore di Boston, Il caso Thomas Crown, Carrie – Lo sguardo di Satana, probabilmente ben noti a McGuire. Per rimanere ai fumetti, invece, lo stesso Ware citava come possibili ispirazioni di McGuire The Malpractice Suite di Art Spiegelman e A Short History of America di Robert Crumb, il primo per la scomposizione quasi cubista della vignetta, il secondo per il modo in cui mostra l’evoluzione di uno stesso punto dello spazio nel corso del tempo. Di seguito le due opere citate (quella di Crumb è nella sua versione più recente, con l’aggiunta delle ultime tre vignette).

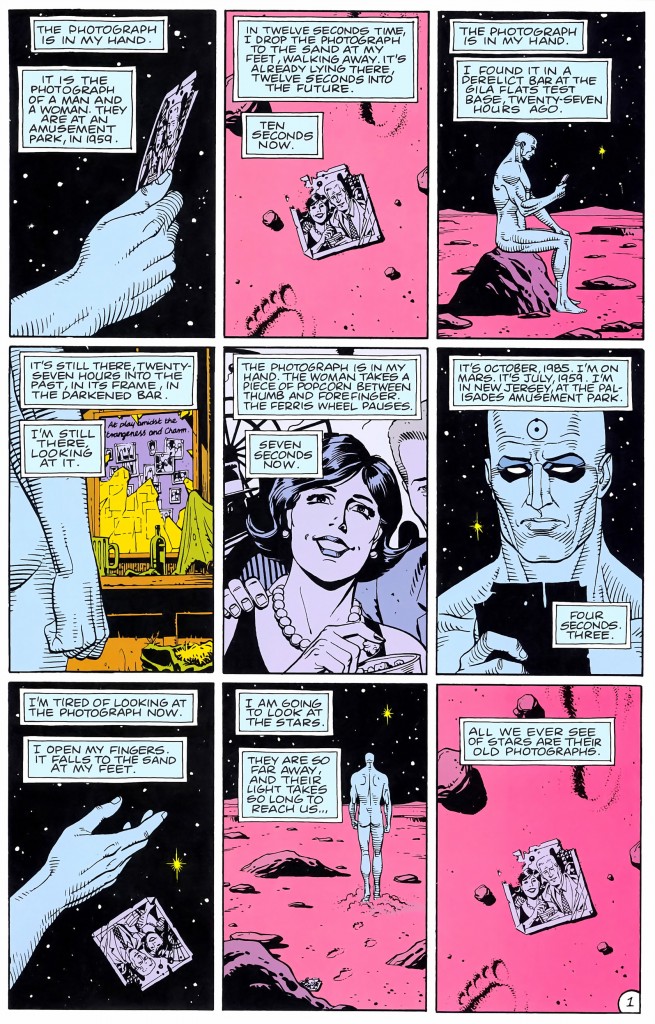

A me, innanzitutto appassionato dei comics nella loro declinazione anglo-americana, quando per la prima volta lessi Here venne banalmente in mente il quarto capitolo di Watchmen di Alan Moore e Dave Gibbons, non solo per il modo in cui la memoria del Dottor Manhattan salta da un anno all’altro, ma anche per come Moore dava veste divulgativa a quel concetto di simultaneità poi diffusissimo nella cultura popolare degli ultimi vent’anni, dal cinema al fumetto alle serie tv. Sicuramente le conoscerete già a memoria, ma queste sono le due pagine iniziali di Watchmen #4.

Subito dopo assistiamo alla scena del 7 agosto 1945 in cui il padre del Dottor Manhattan, dopo aver mostrato al protagonista la prima pagina del New York Times con la notizia della bomba atomica su Hiroshima, prende gli ingranaggi di un orologio e li butta dalla finestra. “Questo cambierà tutto. Ci saranno altre bombe. Sono loro il futuro. E mio figlio dovrà proseguire il mio lavoro obsoleto? (…) La scienza atomica… E’ di questo che il mondo ha bisogno! Basta con gli orologi! Il professor Einstein dice che il tempo varia da luogo a luogo. Hai idea? Se il tempo non è reale, a che servono gli orologiai, eh?”. Se il tempo è obsoleto nella realtà, figuriamoci nel fumetto, dove poco ci vuole a rompere il concetto tradizionale secondo cui i fatti raccontati in una vignetta siano precedenti a quelli che si vedranno nella successiva. E lo stesso vale nella letteratura, dove ci vuole ancor meno ad abbandonare l’idea di romanzo come successione di eventi per raccontare la storia di un luogo, come tra gli altri ha fatto lo stesso Alan Moore con la sua bellissima e sghemba storia di Northampton contenuta in La voce del fuoco.

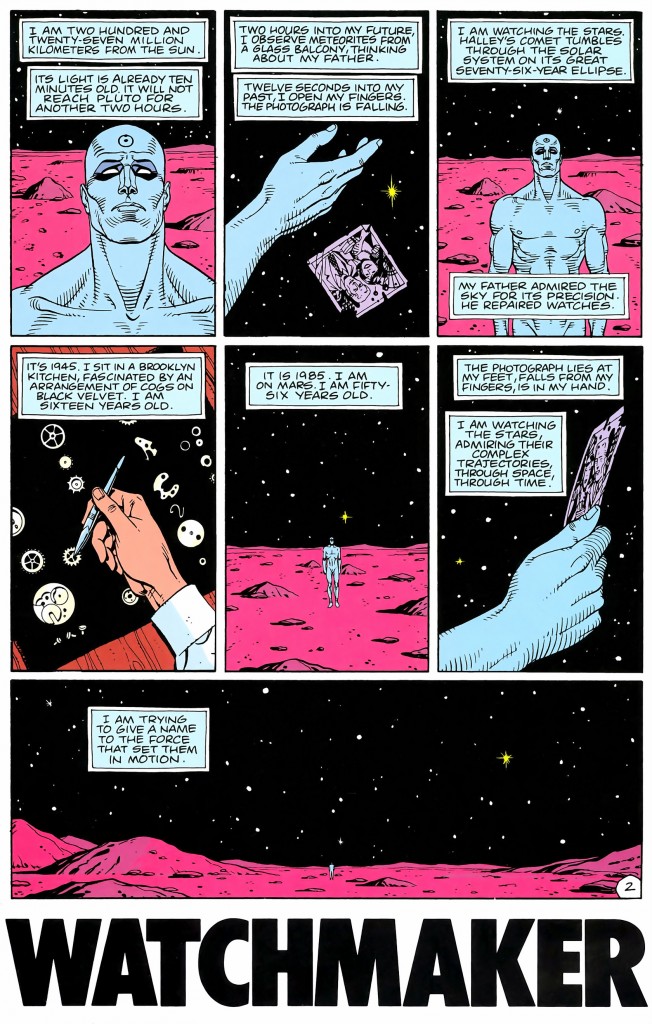

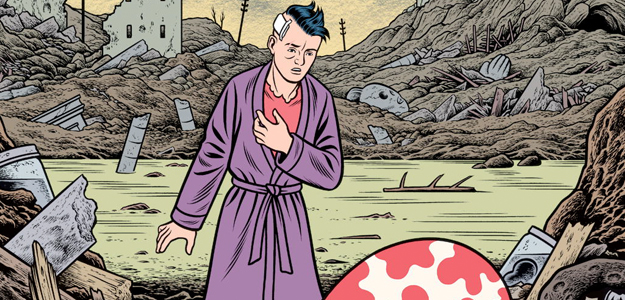

Prima ho usato in modo un po’ criptico l’aggettivo “nuovo” riferendomi a Here. Ma d’altronde ormai ben saprete che McGuire ha rivisitato il concept originale in una nuova edizione, che dopo una lunga gestazione è uscita lo scorso anno sotto forma di un libro a colori di oltre 300 pagine pubblicato da Pantheon Books e arrivato anche in Italia da qualche settimana grazie a Rizzoli Lizard con il prevedibile titolo di Qui. Se qualche fedele lettore di queste pagine si fosse chiesto perché non avevo incluso il volume nella lista dei migliori fumetti del 2014, è perché all’epoca ancora non avevo letto il nuovo Here, dato che una copia spedita in anteprima grazie a qualche aggancio oltreoceano si era perduta nei meandri del sistema postale mondiale e si era infine palesata dopo mesi di attesa, quando il libro era già da un bel po’ di tempo nelle librerie.

Here parla dell’essere umano, sia nel senso di “umanità” che in quello di “uomo” e l’opposizione o meglio la giustapposizione di questi due concetti è ancora più evidente nella versione graphic novel. Se le sei pagine originali sfoggiavano una narrazione convulsa, veloce, dinamica, rappresentando come nessun fumetto aveva mai fatto prima le dinamiche del pensiero, le 300 pagine della versione 2014 sono lente, pacate, a tratti malinconiche nel modo di accostare l’inesorabilità del Tempo e della Storia alle piccole vicende quotidiane delle persone comuni, a ricordarci, come diceva McGuire, che noi sperimentiamo soltanto una parte delle possibilità di questo mondo, che quello che accade nel nostro piccolo è niente rispetto alle ere geologiche, all’estinzione delle specie, a un futuro che – almeno secondo quanto dicono queste pagine – riporterà la Terra indietro, verso le sue origini. Il tutto è ovviamente riportato secondo la sensibilità di un uomo occidentale che ha vissuto e vive tra il XX e il XXI secolo, ma non potrebbe essere altrimenti, dato che pur trattando di temi universali si tratta sempre di un’opera personale, in cui l’autore ci ha inevitabilmente messo del suo.

Il solito Chris Ware è tornato su Here per parlare delle sua nuova incarnazione, dicendo che “con quelle prime sei pagine nel 1989, McGuire ha introdotto un modo nuovo di fare una striscia a fumetti, ma con questo volume, nel 2014, ha introdotto un nuovo modo di fare un libro”. Ma cosa c’è, dunque, dentro queste 300 pagine? Innanzitutto c’è una visione più ampia di quel famoso spicchio di realtà. Se nella striscia infatti l’unità narrativa era rappresentata dalla vignetta, qui è costituita dalla doppia pagina, cosa che permette all’autore di allargare la prospettiva mostrandoci non solo quell’angolo in alto a sinistra (secondo la nostra percezione) ma anche altre porzioni delle stanza. Per esempio guardando la prima versione non avevamo mai visto il camino, lo specchio, quel tavolino, quell’abat-jour. Inoltre non avevamo mai visto i colori, realizzati grazie all’aiuto di Min Choi, Maëlle Doliveux, Keren Katz, definiti come “Team Here” perché hanno aiutato l’autore negli aspetti più tecnici del processo creativo, portando alla realizzazione di un affascinante ibrido tra matite, computer grafica, colori digitali e splendidi acquerelli. L’uso del colore cambia l’estetica della storia e anche se la tavolozza cromatica è molto ampia, a prevalere sono i temi tenui del giallo/marrone/ocra, che ricreano un mood simile a quello dei quadri di Edward Hopper. E spesso, vedendo quel salotto e le sue evoluzioni nel corso del Novecento, sembra di stare in un libro di qualche maestro del racconto americano come Richard Yates o Raymond Carver.

D’altronde Here è a suo modo un libro di racconti, in cui brevi storie si accumulano, si sviluppano e a volte si intrecciano. Ma è anche un susseguirsi di associazioni di idee, di temi che vengono trattati per qualche pagina per poi lasciare spazio ad altri, mentre le finestre si aprono e si incastrano tra loro e gli anni vanno avanti, indietro, avanti e ancora indietro. Dentro c’è la rappresentazione di panorami astratti dai colori vivacissimi nel 3.000.500.000 a.C., di animali preistorici nel 10.000 a.C., di splendidi e incontaminati scenari lacustri nell’8000 a.C. come nel 1203 e nel 1307, di due indigeni che fanno l’amore nel 1609, di Benjamin Franklin che discute di politica con il figlio nel 1775, di case che vengono costruite nel 1907, della vita secondo le forme ben conosciute del XX secolo (poi raccontata da una guida turistica nel 2213), del mondo dopo un non meglio identificato evento catastrofico nel 2313, di animali a noi sconosciuti che vagano nell’oscurità del 10175, di forme di vita nuove e colorate che appaiono nel 22175. Ci sono foto di famiglia fatte in anni diversi sullo stesso divano, madri che tengono in braccio i loro figli nel 1924 come nel 1945, nel 1949 e nel 1988, feste di carnevale, party, bambine che ballano. C’è una bellissima pagina ambientata nel 1949 in cui lo specchio sopra al camino cade e mentre una vignetta più grande ci mostra l’acqua che entra in casa dalla finestra in una notte del 2111, ci sono tantissime finestrelle che ci mostrano piatti e bicchieri che si rompono e insulti che volano letteralmente in aria, neanche fossimo in un trattato sociologico sull’evoluzione del linguaggio. E poi c’è la storia della stanza, con la carta da parati che viene sostituita nel 1949 per poi essere coperta dalla pittura nel 1960, lo specchio sopra al camino che lascia spazio a un quadro, poi sostituito da un altro specchio, quindi da un televisore da parete che diventerà obsoleto nel 2050 davanti alle nuove tecnologie da salotto. C’è anche il dramma in Here, dato che nelle prime pagine siamo nel 1989 e un uomo dopo aver ascoltato una barzelletta inizia a ridere, quindi a tossire e infine cade a terra, anche se per vedere la reazione dei familiari dovremo aspettare di arrivare quasi a metà volume, in una pagina ambientata sempre nel 1989 ma in cui c’è anche una donna che nel 1960 dice “Did you lose something?”, collegandosi alla morte dell’uomo e contemporaneamente dando il via a una sequenza di diverse pagine con personaggi che perdono oggetti personali oppure la testa, la vista, l’udito.

Capita raramente di trovare delle opere formalmente innovative che siano in grado al tempo stesso di parlare al cuore del lettore. Here è una di queste e l’effetto ottenuto da McGuire è ancora più straordinario se pensiamo che riesce a pungolare, a emozionare, a stupire senza fare uso di trame né di protagonisti, ma semplicemente raccontando la Storia e le storie, il grande e il piccolo, il grave e l’irrilevante, il serio e il faceto. La metafora più efficace di tutto ciò è nelle pagine iniziali, quando nel 1957, l’anno da cui partiva la versione originale di Here, una donna entra nella stanza e si chiede “Hmm… Now why did I come in here again?”. La domanda – autobiografica e metanarrativa – rimane in sospeso mentre leggiamo e la risposta arriva soltanto alla fine: la donna è entrata per prendere un libro. E – come cantavano i Pavement – tutto finisce qui.

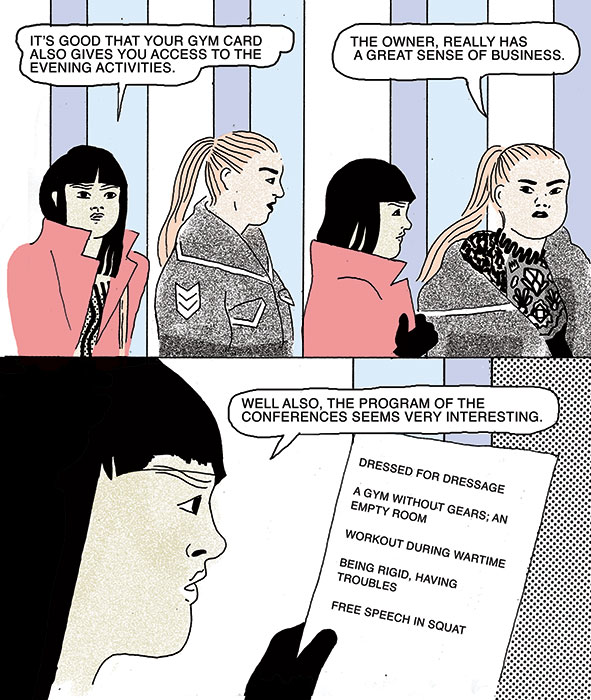

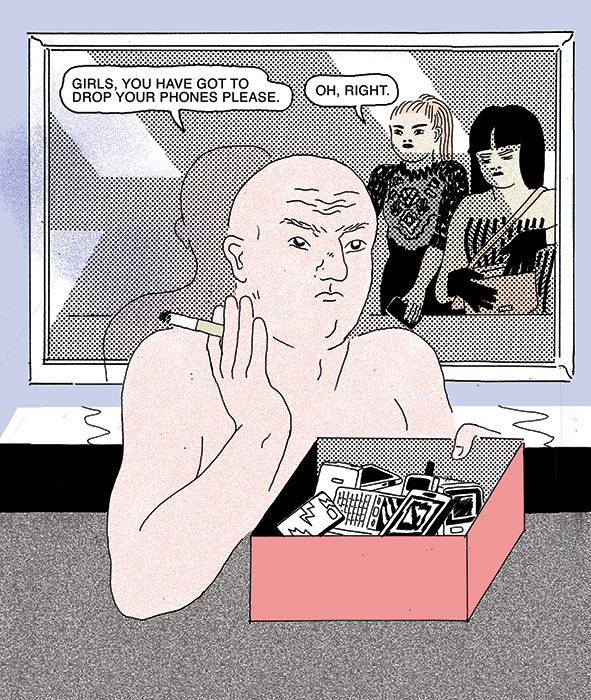

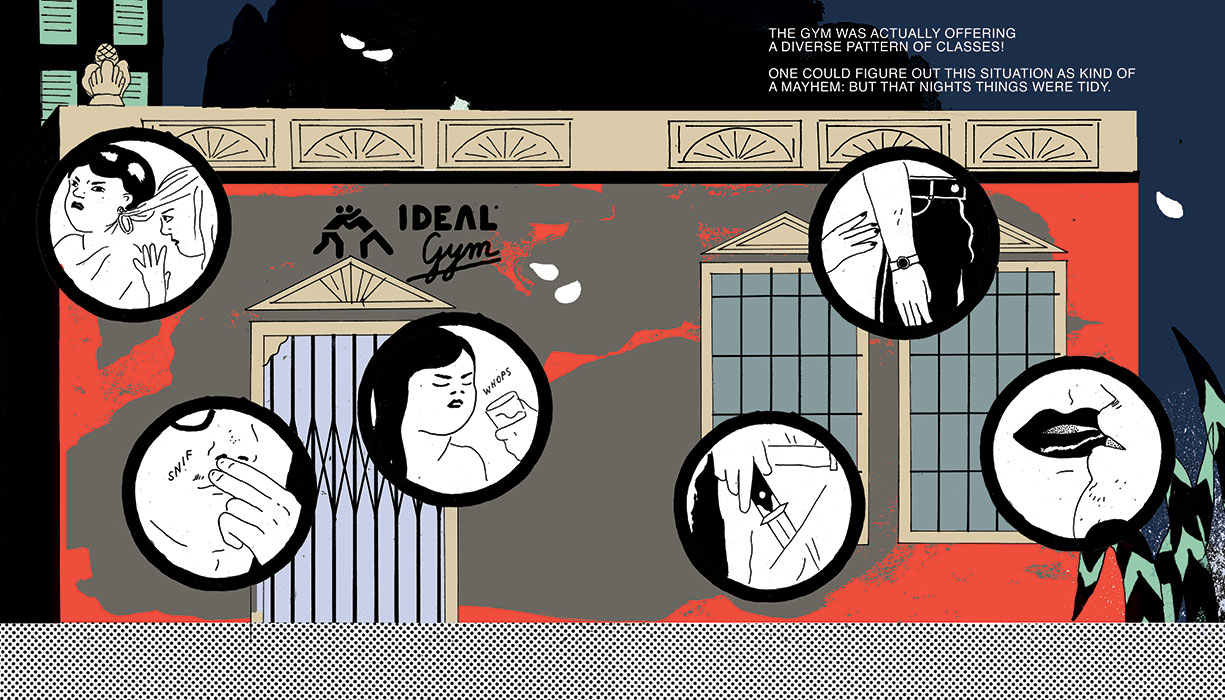

Le prime pagine di “Frontier” #8 di Anna Deflorian

Ha esordito lo scorso fine settimana al Toronto Comic Arts Festival l’ottavo numero di Frontier, l’antologia monografica pubblicata dalla Youth In Decline di San Francisco, realizzato dalla nostra Anna Deflorian. Ryan Sands, patron della casa editrice, aveva conosciuto la Deflorian grazie al contributo dell’illustratrice trentina al nono numero dell’antologia baltica š!. Le tematiche di quel breve racconto e le inquietudini, le pulsioni, le emozioni nascoste delle protagoniste di Roghi, volume del 2013 targato Canicola Edizioni, tornano in queste pagine. Due donne, un uomo incontrato in palestra, un cellulare smarrito con qualche foto osé sono gli elementi di una narrazione scandita attraverso tavole finemente decorate e dalle geometrie inusuali. Di seguito le prime pagine di Faith in Strangers.

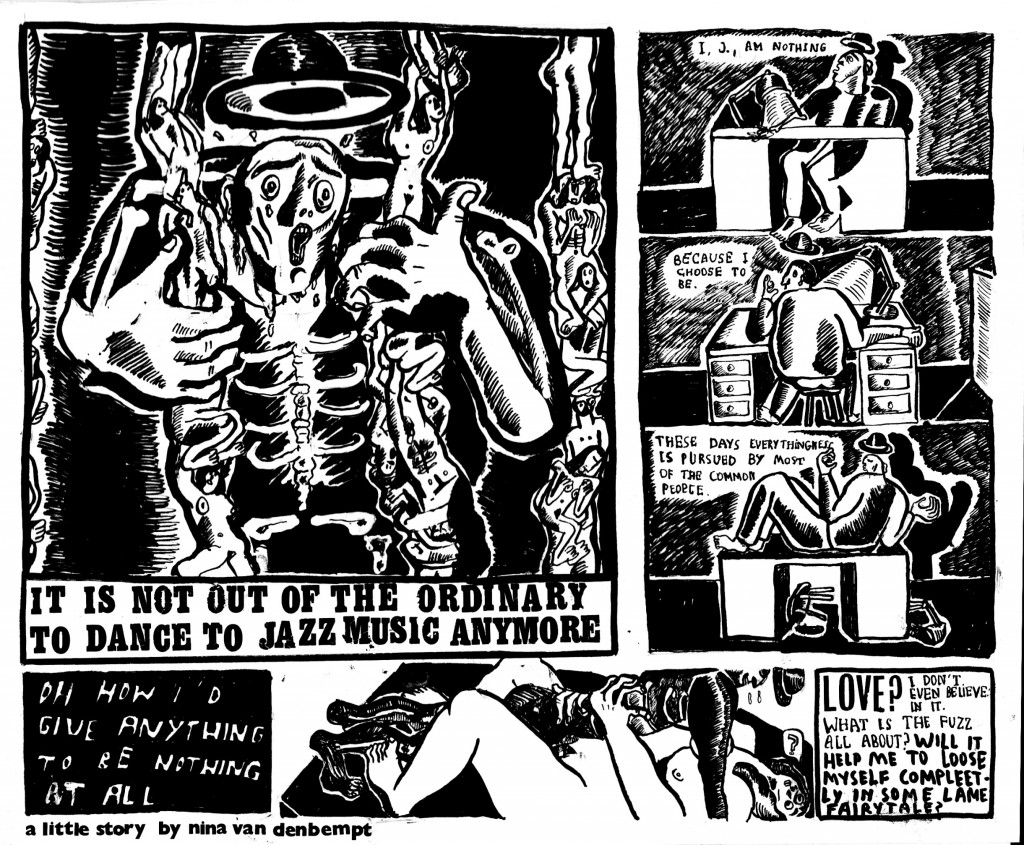

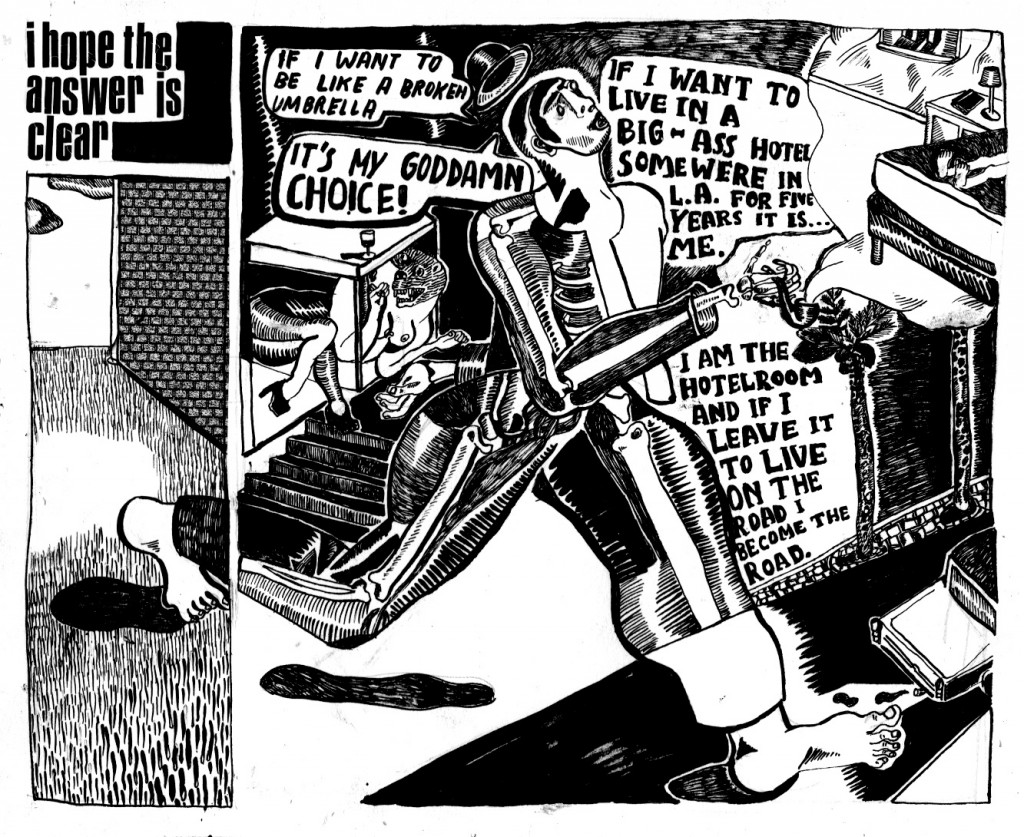

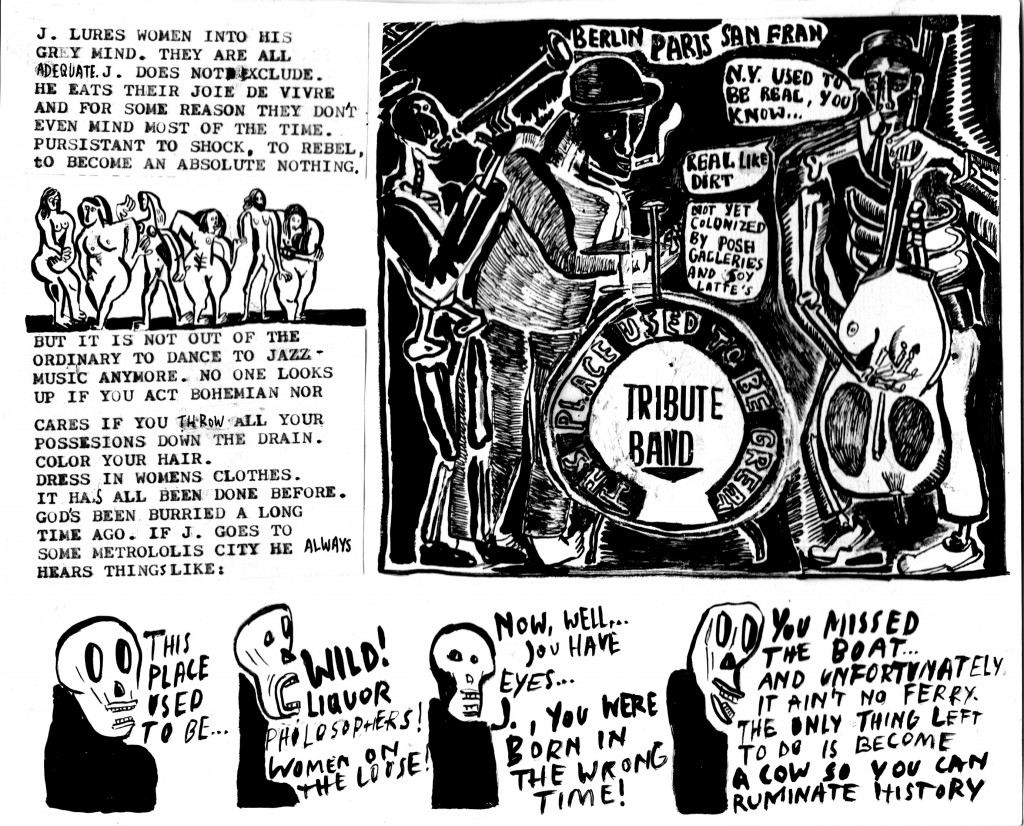

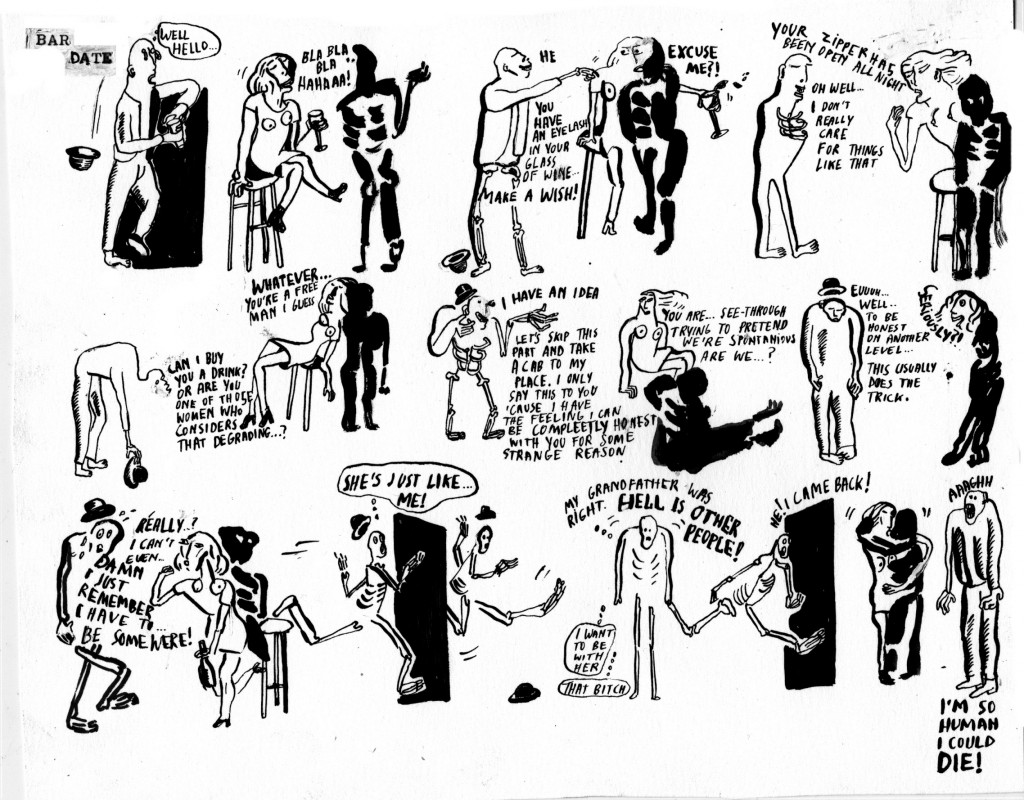

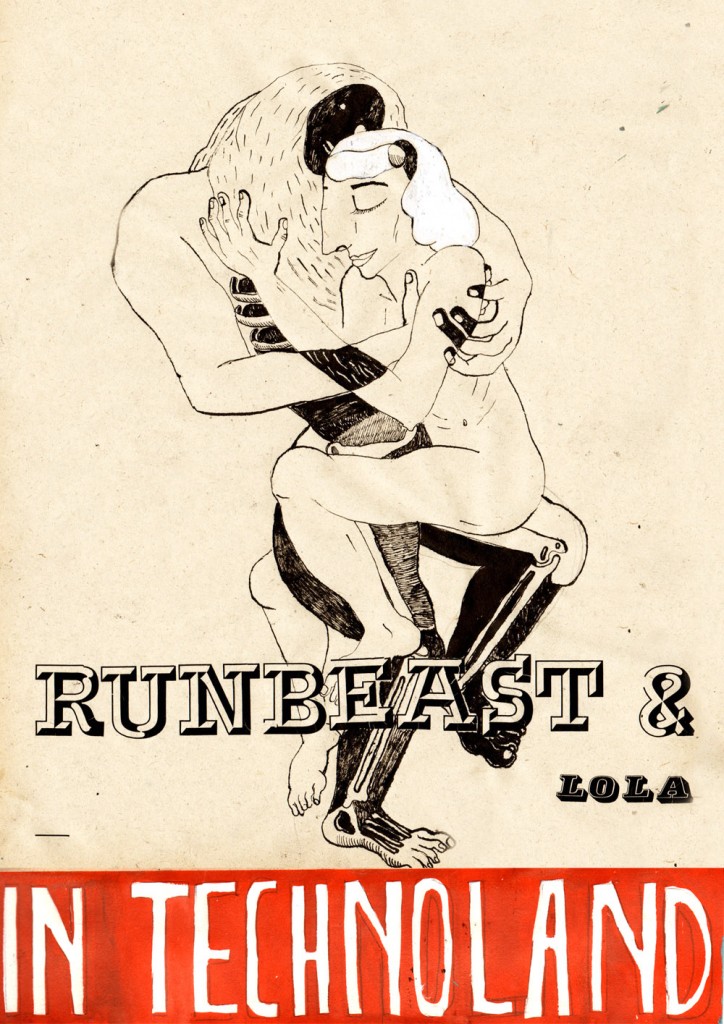

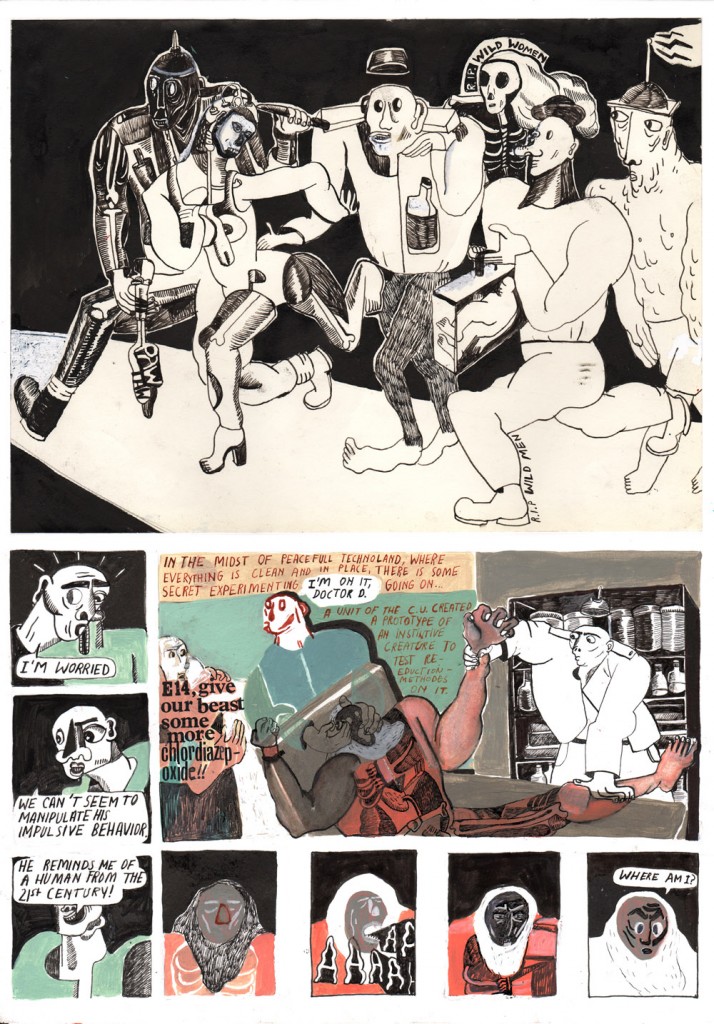

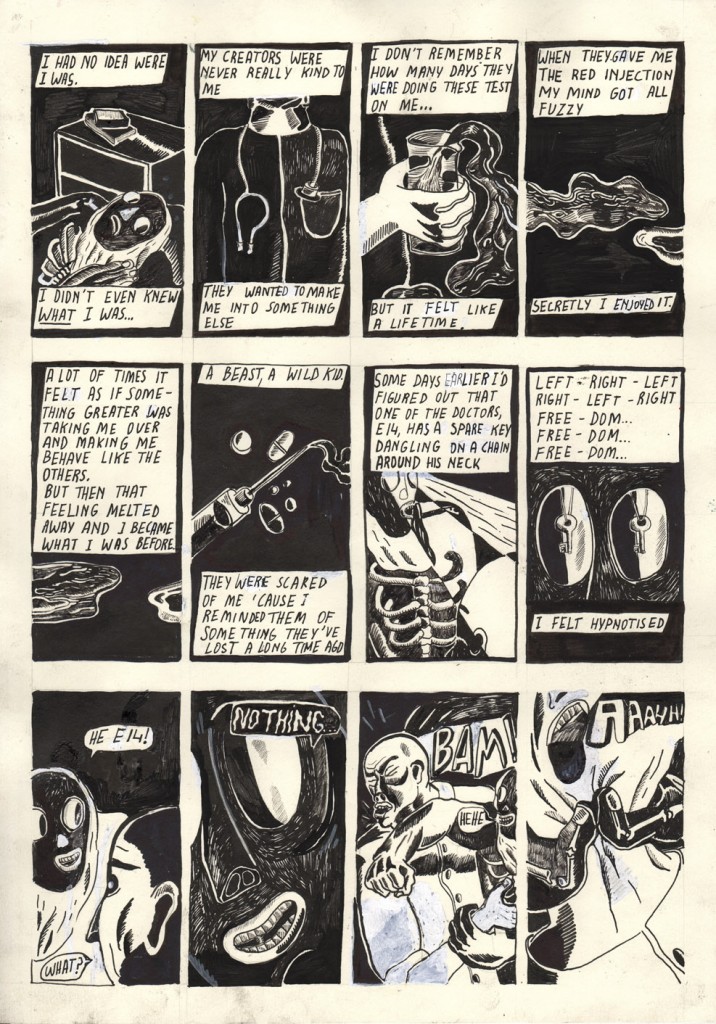

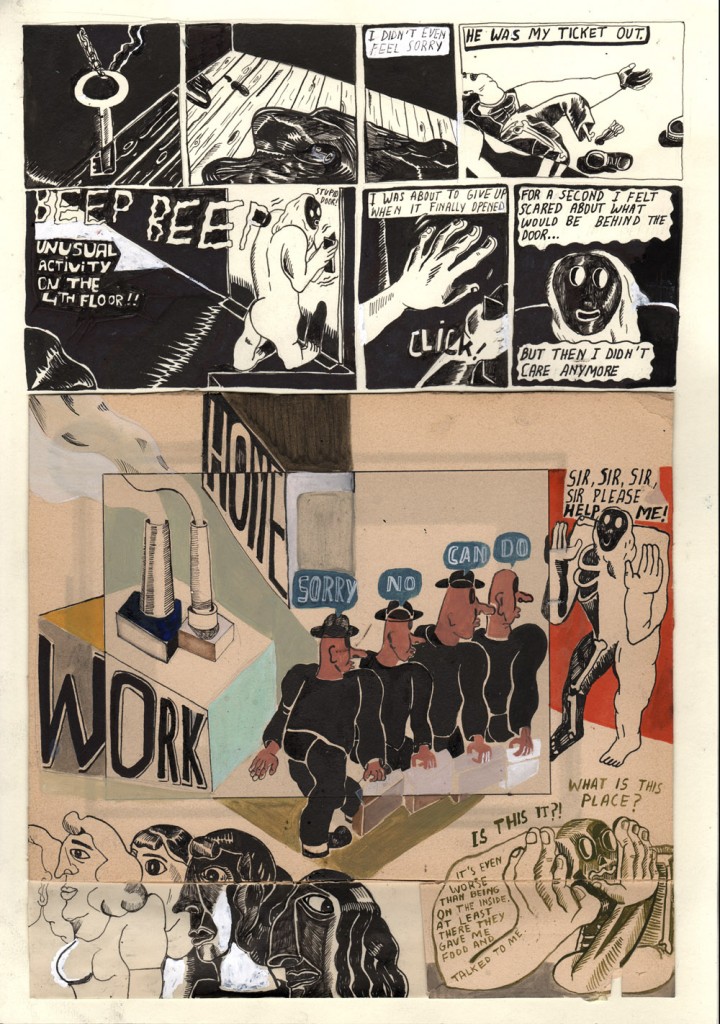

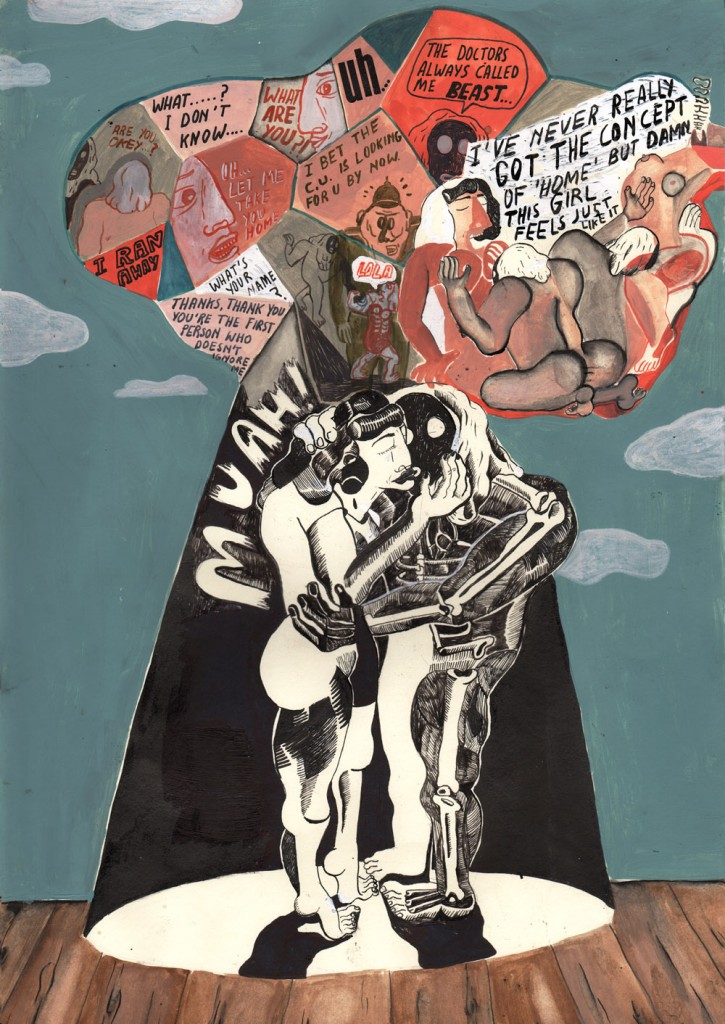

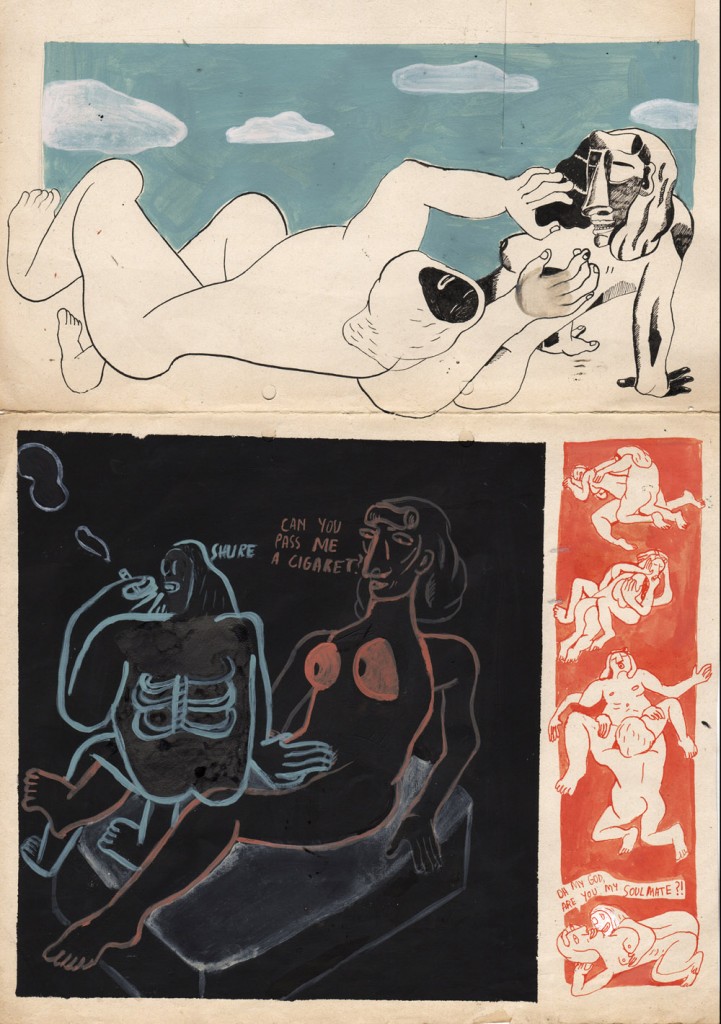

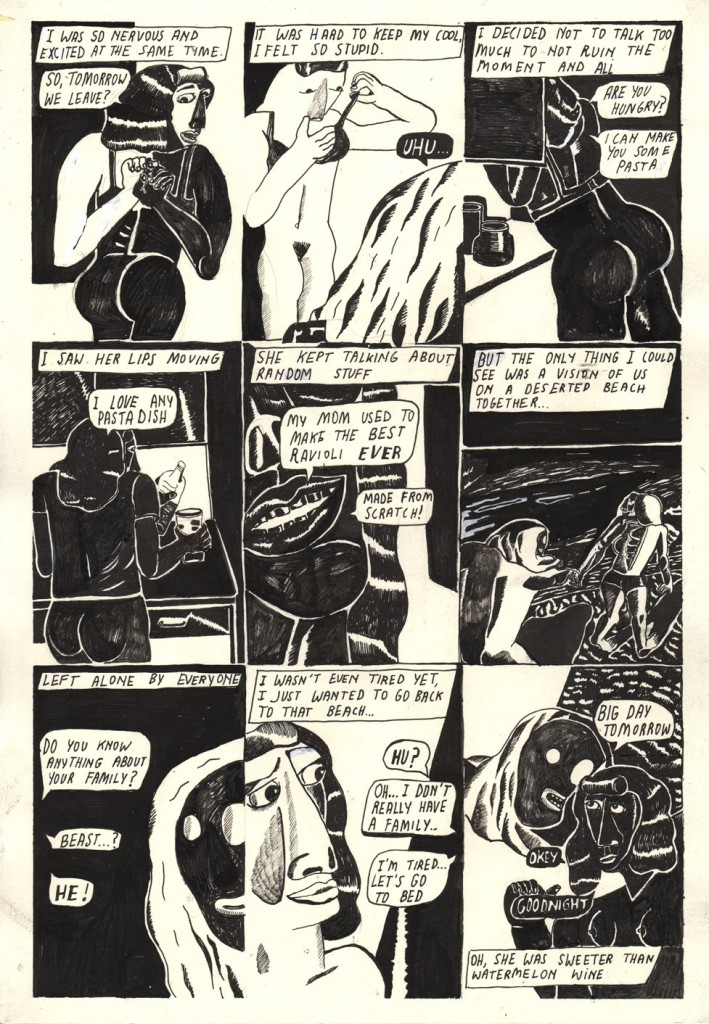

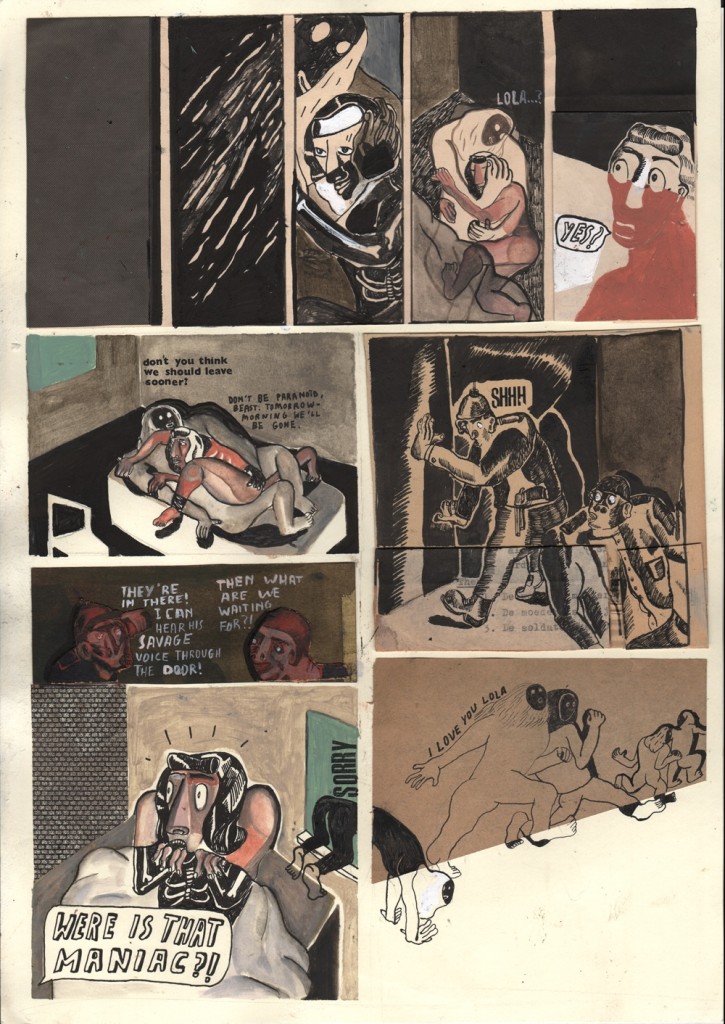

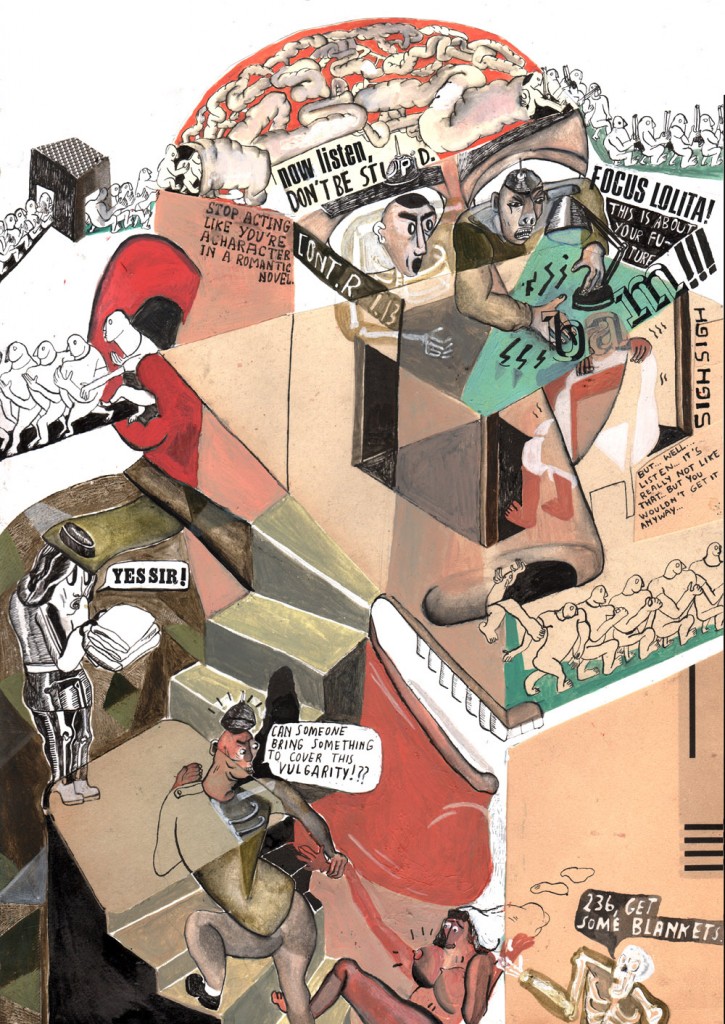

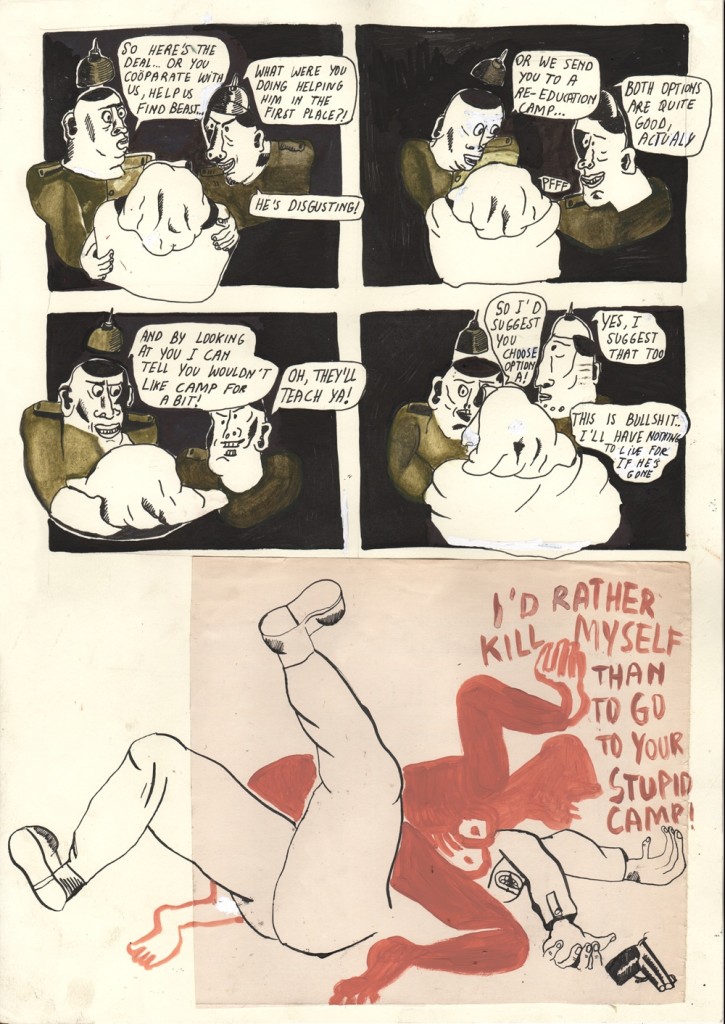

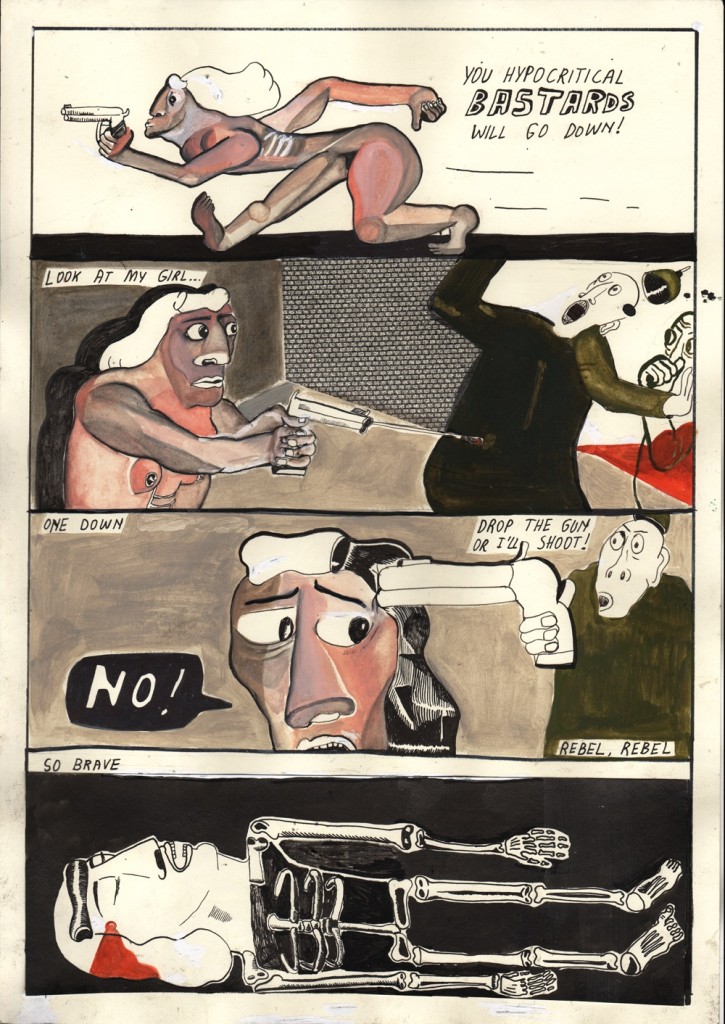

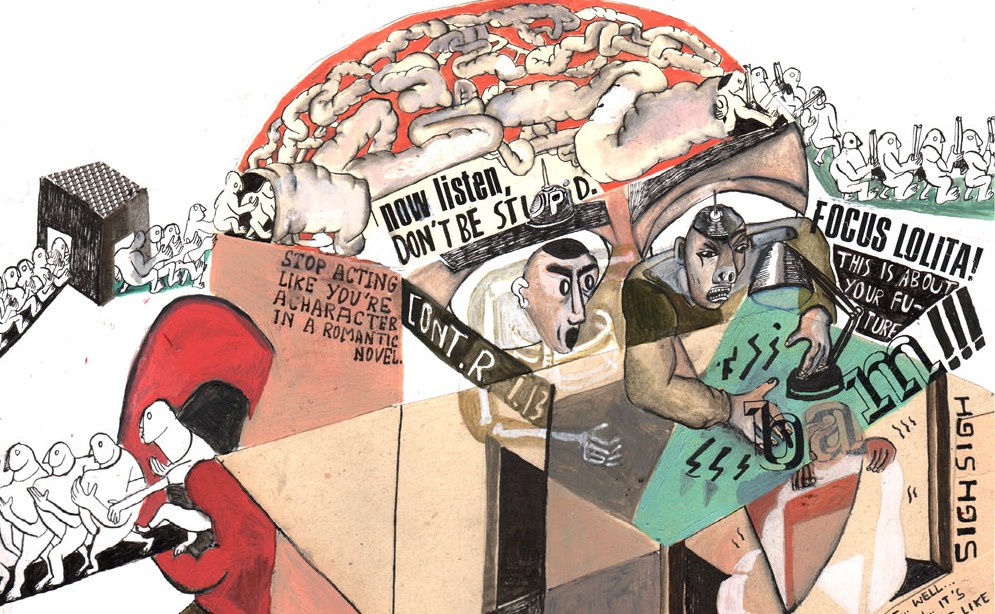

Due fumetti di Nina Van Denbempt

Nina Van Denbempt è un’autrice belga classe ’89, cresciuta artisticamente a Gent, splendida cittadina delle Fiandre che di recente ha sfornato i talenti di Brecht Evens e Brecht Vandenbroucke. Insieme ad alcune compagne della scuola d’arte Sint-Lucas, dove si è diplomata in illustrazione, Nina ha formato il collettivo Tieten Met Haar ed è nel quarto numero del’omonima antologia che ho visto per la prima volta il suo lavoro, in cui i corpi deformati, il lettering irregolare, la giustapposizione di tecniche diverse danno vita a pagine coraggiose e mai banali, come potete vedere dai due fumetti in basso. Il primo è It is not out of the ordinary to dance to jazz music anymore, una storia di quattro pagine vista sia sull’antologia Tieten Met Haar che sulla zine autoprodotta Captain Foggy Brain, caratterizzata da un lirismo stemperato dalla giusta dose di ironia. Uno dei leitmotiv dell’opera della cartoonist belga sembra la banalità del quotidiano e dei suoi rituali e si trova anche nella seconda proposta, Runbeast & Lola in Technoland, dalla trama più strutturata e ambientata in un futuro regime repressivo, con un uso originale del colore. Nina è attualmente a lavoro sulla sua prima opera lunga, Barbarians, una storia d’amore sullo sfondo di un’Europa post-apocalittica.

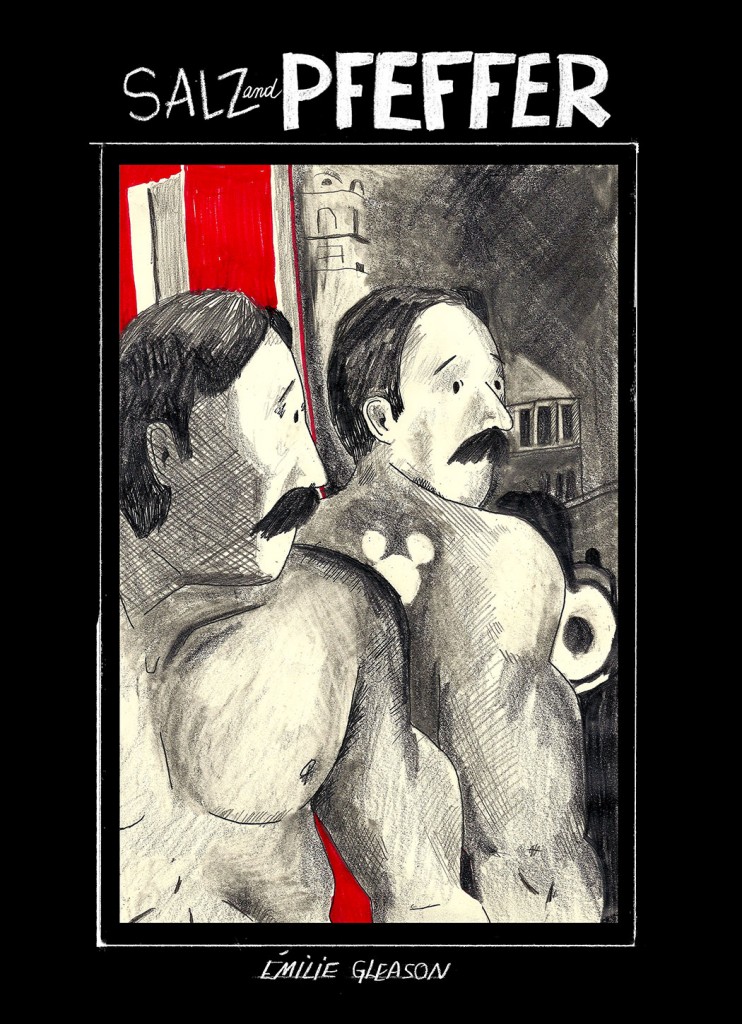

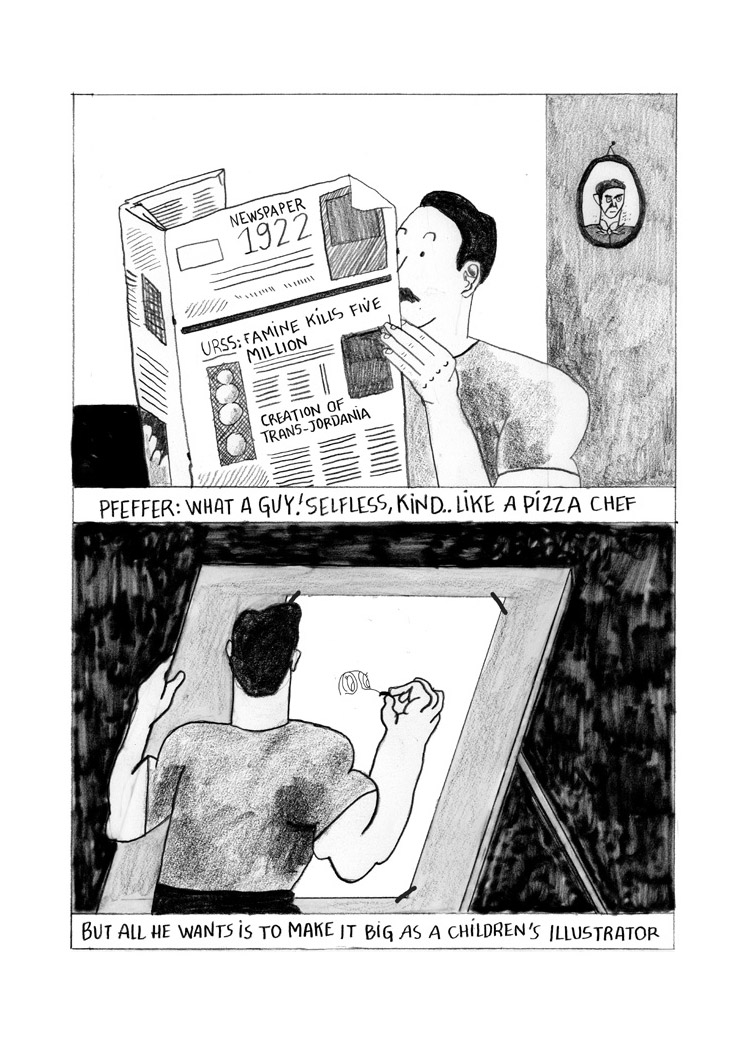

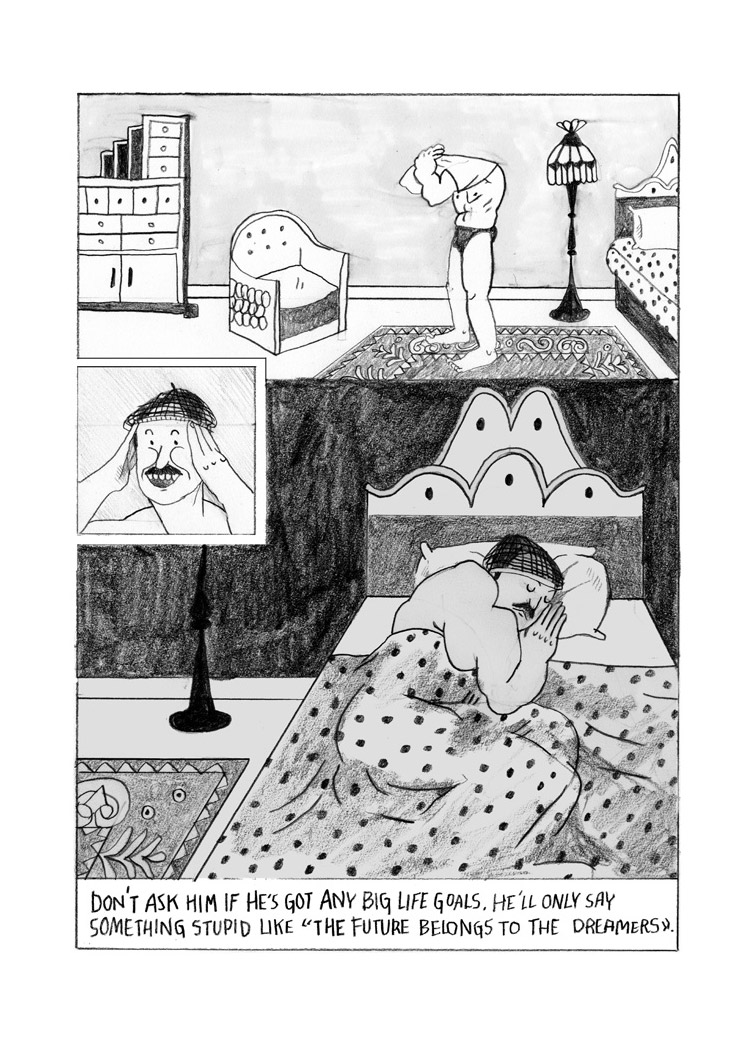

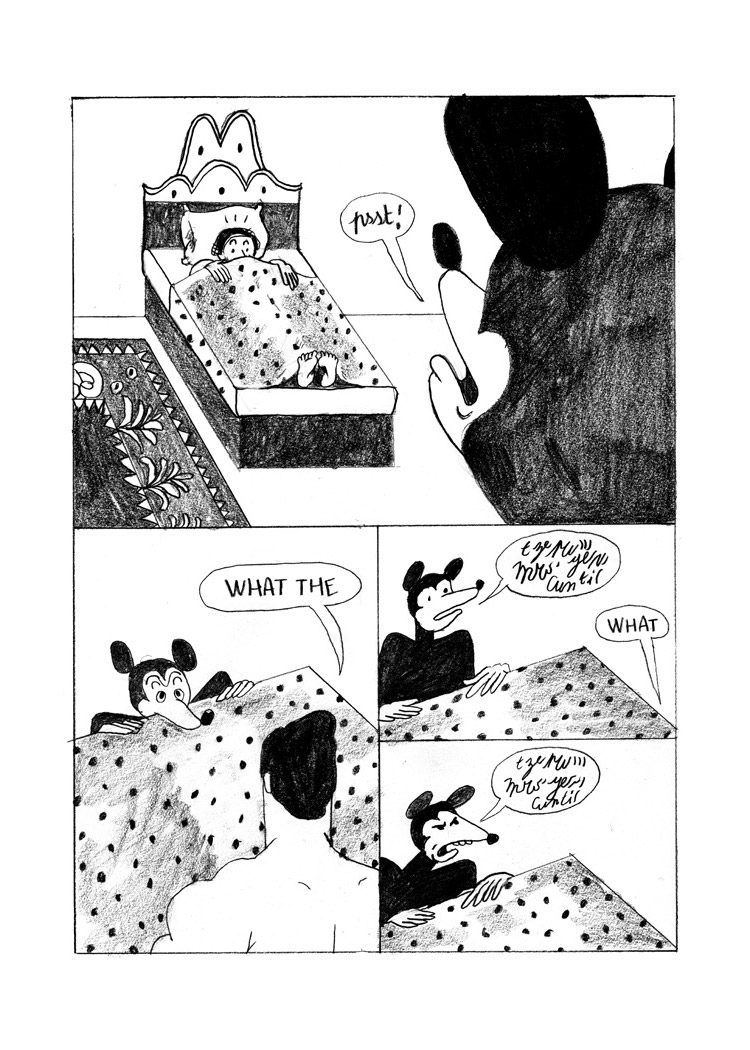

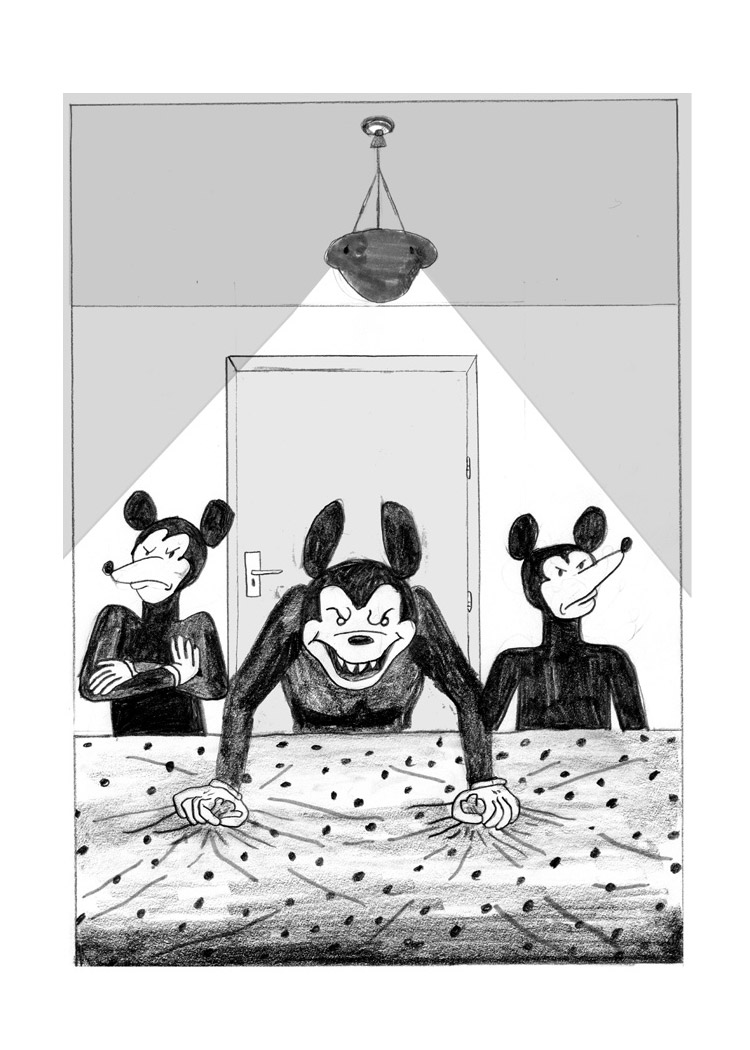

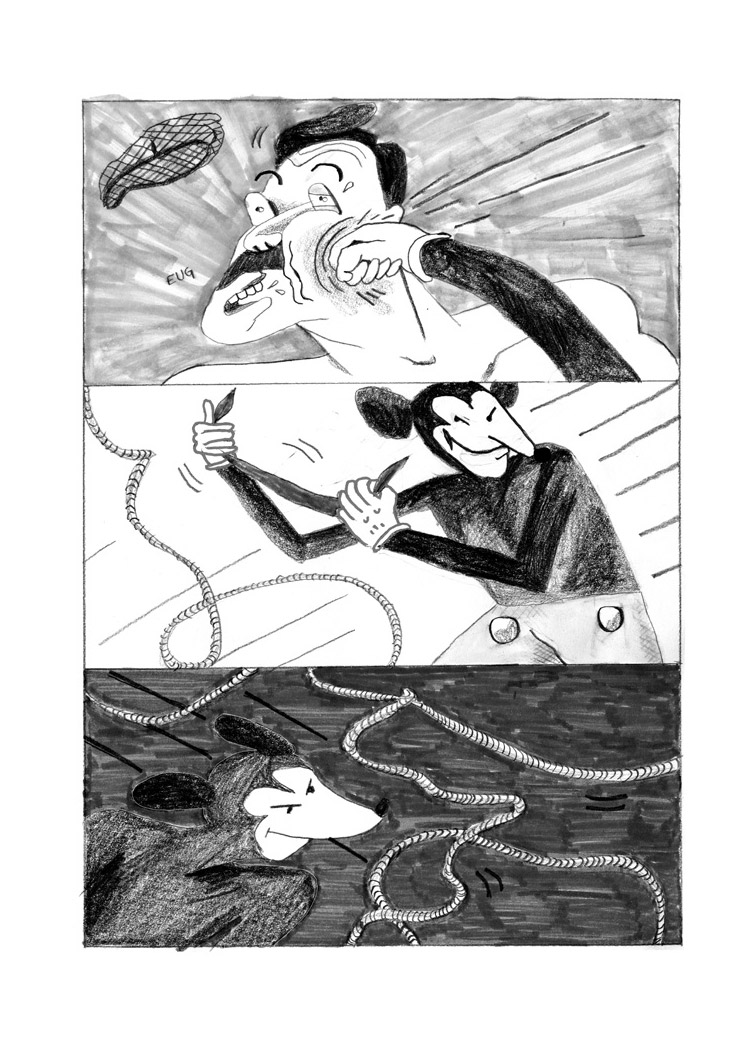

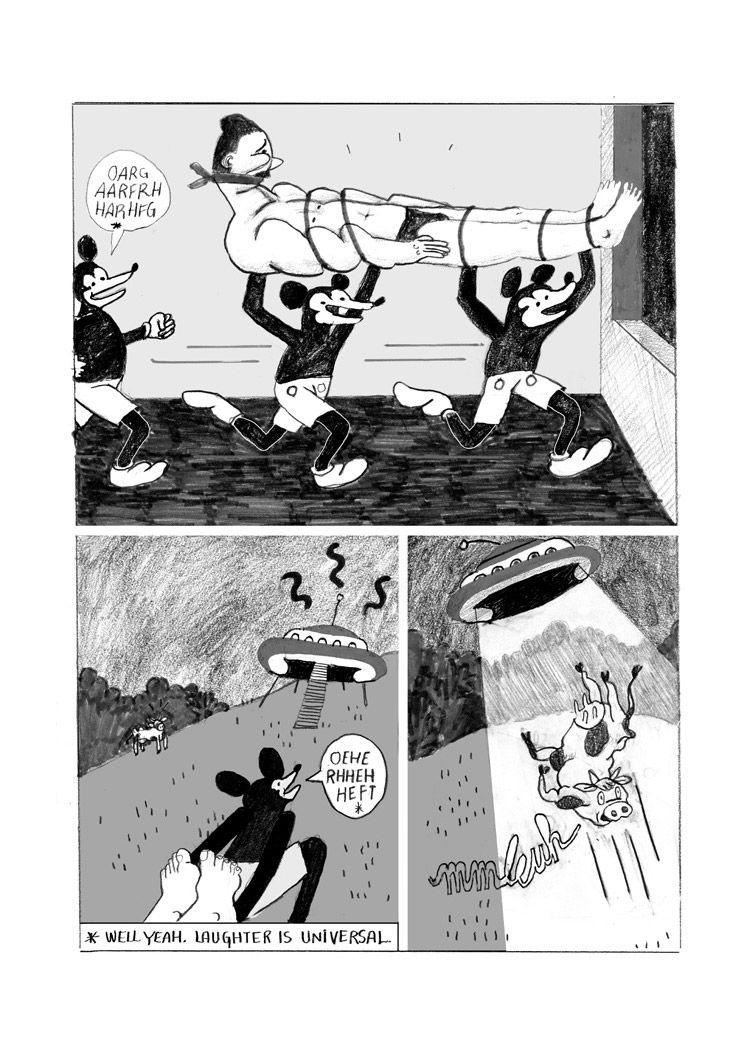

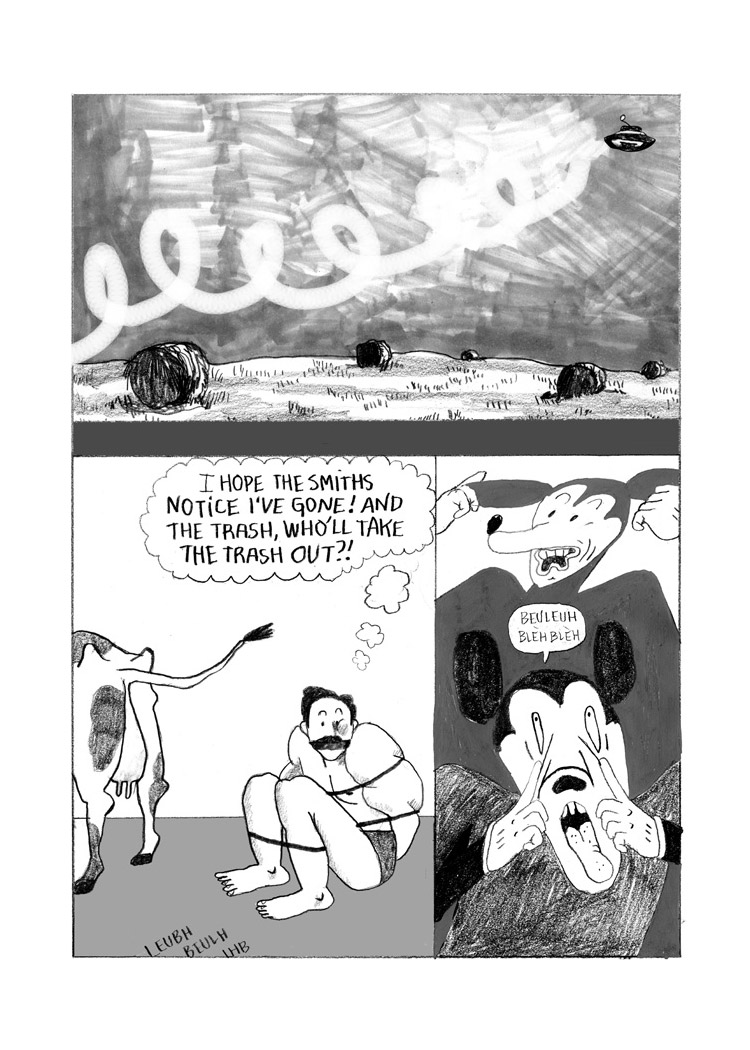

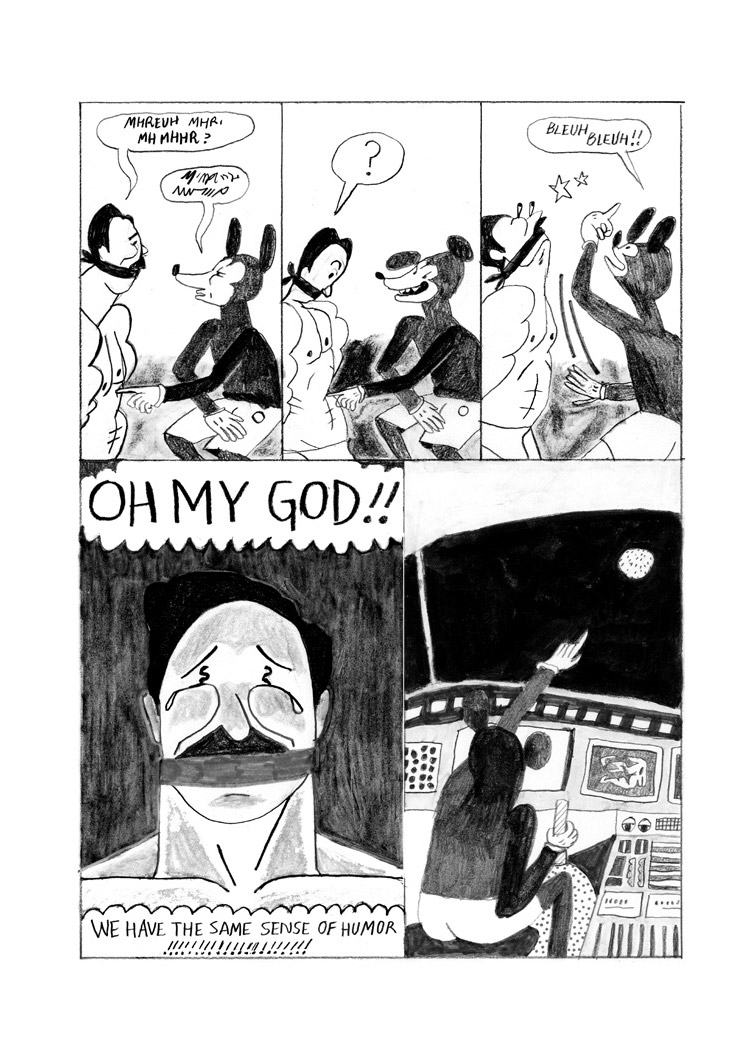

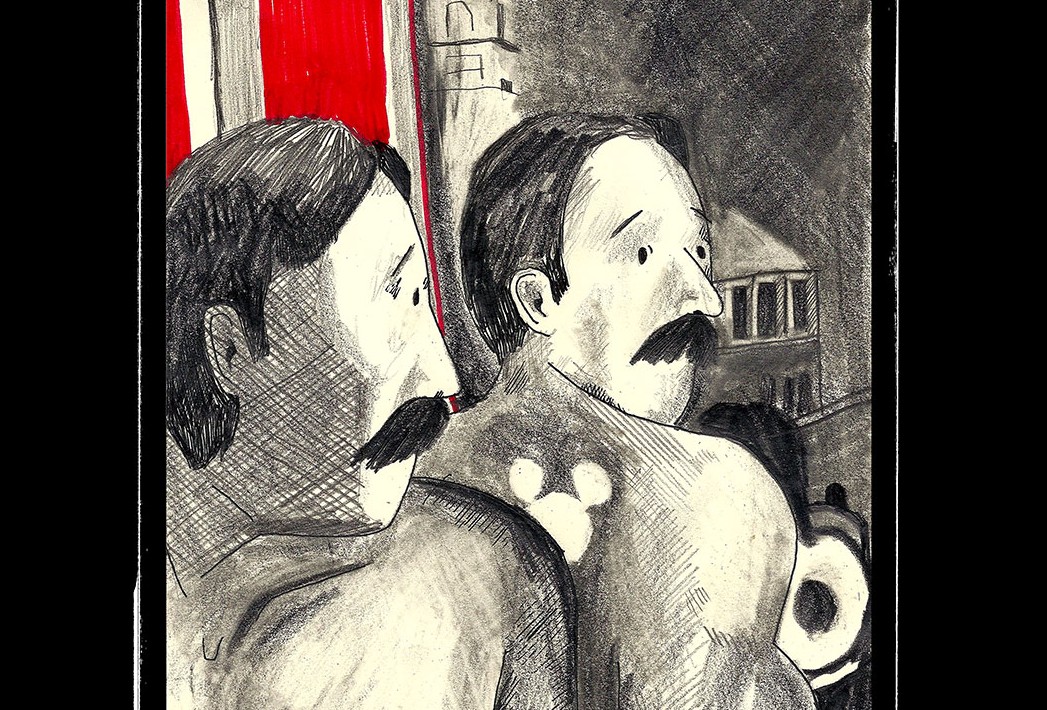

“Salz and Pfeffer” di Émilie Gleason, un’anteprima

Nata in Messico, Émilie Gleason ha vissuto tra Belgio e Francia e sbarca ora negli Stati Uniti con il suo primo libro per il mercato nord-americano, pubblicato dalla 2D Cloud di Minneapolis e presentato lo scorso fine settimana al Toronto Comic Arts Festival alla presenza dell’autrice. Un uomo baffuto, ordinato, rispettabile, Pfeffer sogna di fare il disegnatore per bambini ma una notte viene rapito dagli alieni, in realtà tre versioni oblunghe e cattive di Mickey Mouse. Salz and Pfeffer è un libro divertente, disegnato con uno stile a matita d’altri tempi e dotato di un forte senso della dinamicità. Il lavoro della Gleason rilegge in chiave cartoon quello di autori come C.F. e Gabriel Corbera e questo viaggio di 76 pagine violento, ironico, surreale merita la vostra attenzione, come d’altronde i lavori autoprodotti dall’autrice, disponibili nel suo negozio online. Di seguito le prime pagine del volume.

Il meglio del Web – 7/5/2015

Secondo appuntamento con questa rassegna di notizie, link e segnalazioni varie. Iniziamo dalle novità in casa Youth In Decline. La casa editrice di San Francisco ha da poco pubblicato il settimo numero della serie monografica Frontier, a firma Jillian Tamaki, autrice insieme alla cugina Mariko della pluripremiata graphic novel This One Summer, tradotta da Bao Publishing con il titolo E la chiamano estate. Ancora non ho potuto vederlo di persona, ma la recensione di Alex Hoffman su The Sequential State non fa che incuriosirmi ulteriormente. SexCoven, questo il titolo della storia, è ambientata all’inizio dell’epoca del file sharing e parla di un culto legato a un misterioso file mp3. Intanto sono disponibili le prime immagini dell’ottavo albo di Frontier, firmato dall’italiana Anna Deflorian. E sul blog della casa editrice di Ryan Sands vengono riproposte le interviste agli autori dei precedenti numeri della serie.

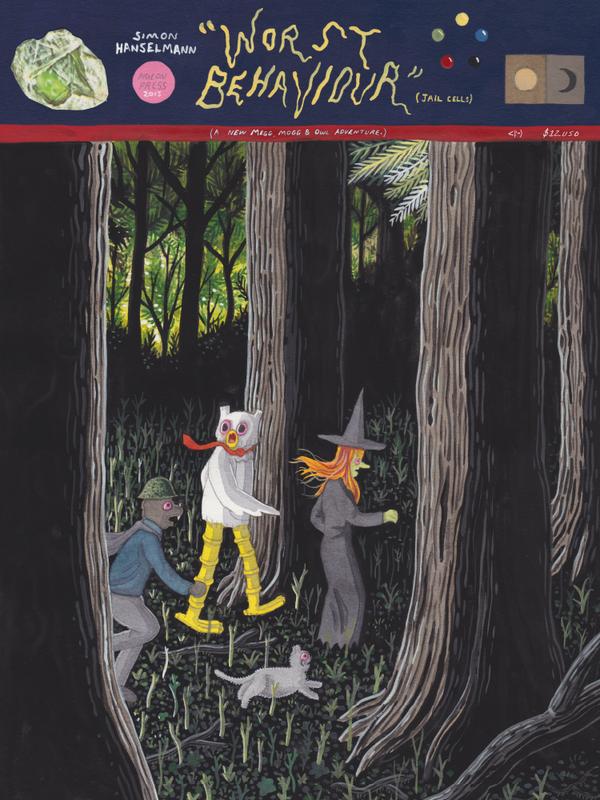

A proposito di novità editoriali, diventa sempre più ricca (ed è anche parziale, dato che mancano gran parte dei mini-comics) la lista dei fumetti che debutteranno al Toronto Comic Arts Festival del 9 e 10 maggio. Tra questi Worst Behaviour di Simon Hanselmann, una nuova avventura di circa 50 pagine di Megg, Mogg e Owl, in uscita per la Pigeon Press di Alvin Buenaventura, già editore di In the Garden of Evil di Burns e Killoffer. Intanto Fantagraphics annuncia per l’autunno il seguito del fortunato Megahex. Il nuovo volume si intitola Megg & Mogg in Amsterdam e raccoglie le storie pubblicate su Vice.com. Hanselmann ha parlato di recente dei suoi progetti futuri e del suo processo creativo in un’intervista al magazine Darling Sleeper.

Rimanendo in tema, arrivano finalmente sul canale You Tube della Small Press Expo i video dell’edizione 2014 del festival statunitense, tra cui potete trovare anche quello che riproduce il divertente incontro con Hanselmann, Michael DeForge e Patrick Kyle. Tra gli altri vi segnalo quello con Charles Burns, che parla della sua infanzia e legge alcuni passaggi da Sugar Skull, di prossima uscita per Rizzoli Lizard.

Il nuovo fumetto di Jordan Crane si intitola The Dark Nothing e sarà pubblicato in un’edizione limitata di 200 copie. La storia verrà poi ristampata, in una versione leggermente diversa, sul quinto e voluminoso numero di Uptight, in uscita per Fantagraphics. Per chi non conoscesse Crane, sul sito What Things Do potete leggere alcuni dei suoi fumetti.

Nel post su Daniel Clowes di qualche giorno fa, dicevo che la scritta “Patience” diffusa come prima immagine del suo nuovo fumetto, in uscita a marzo 2016, sembrava più un invito ai lettori che il titolo del libro. E invece il titolo di questa storia di 180 pagine che avrà come tema il viaggio nel tempo sarà proprio Patience, come ha anticipato lo stesso autore in questa intervista al New York Times. Ieri è arrivato anche l’annuncio ufficiale di Fantagraphics, che ha definito Patience “an indescribable psychedelic science-fiction love story”. Intanto l’autore continua a rilasciare interviste, tra cui vi segnalo quella realizzata da Ray Pride per il sito Newcity Lit, che si differenzia dalle altre dato che verte sul rapporto tra l’autore e la sua città di origine, Chicago.

Il sito internet Broken Frontier ha lanciato una campagna Kickstarter per la pubblicazione di una lussuosa antologia di 250 pagine a colori, in formato gigante e copertina rigida. Oltre 40 gli artisti coinvolti, dagli stili più disparati. Tra questi Noah Van Sciver, autore di una storia di 10 pagine su un clown con problemi di rabbia che diventa schiavo degli uomini talpa.

Lo stesso Van Sciver è uno degli autori chiamati da Vice a rileggere i Blobby Boys di Alex Schubert. Tra gli altri Ron Regé Jr., Antoine Cossé, Hellen Jo.

Un Tumblr assolutamente da vedere è quello di Samplerman, di cui potete ammirare un’immagine qui sotto. Per approfondire vi rimando all’intervista su It’s Nice That.

Con l’uscita di Avengers: Age of Ultron, fioccano articoli, immagini e quant’altro in qualche modo legati ai contenuti del film. Una delle proposte migliori è del sempre interessante blog Diversion of the Groovy Kind, che porta con orgoglio il sottotitolo “1970’s Comic Books Nostalgia”. Sembrerà fuori tono su un sito che si chiama Just Indie Comics, ma non posso fare a meno di consigliarvi questa sequenza di splash page con protagonisti Scarlet, Quicksilver e Visione a firma John e Sal Buscema, Don Heck, Barry Windsor-Smith, Rich Buckler, John Byrne e altri ancora.

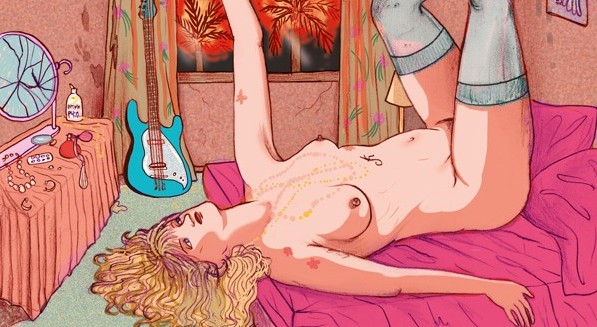

Le notti del Rock Motel

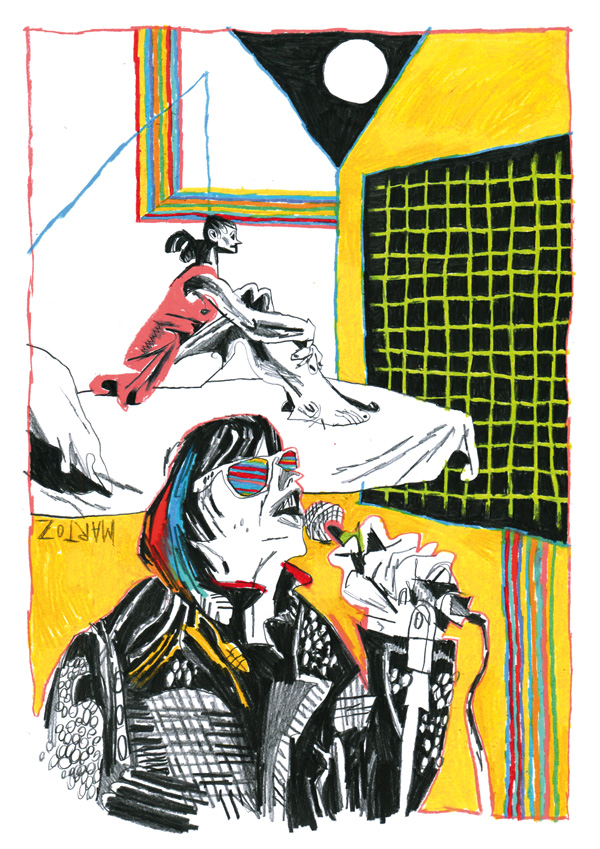

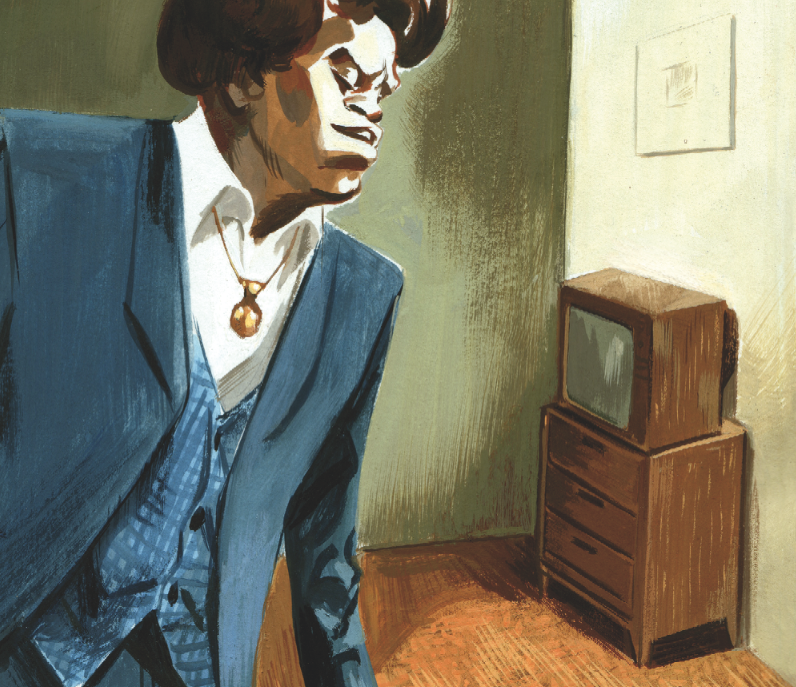

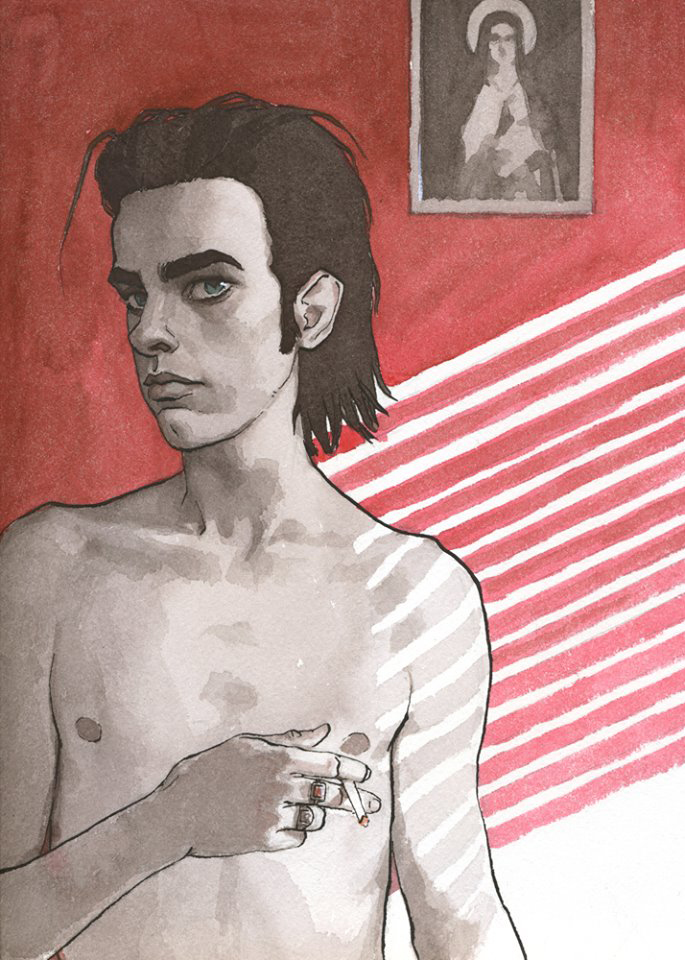

Dopo l’art book 64 Kamasutra, l’associazione culturale Squame torna con un nuovo libro illustrato da oltre 60 giovani artisti internazionali. Il tema questa volta è rappresentato dalle stanze di motel delle rock star, ricostruite a partire dall’immaginario artistico ed estetico dei musicisti, come potete ben vedere dal disegno di apertura, una Courtney Love colta in un momento di relax da Cristina Portolano. Rock Motel uscirà a giugno ma la campagna di crowdfunding è in corso soltanto fino al 15 maggio su Ulule. Il pacchetto base, che include libro di 144 pagine e tre cartoline, costa 17 euro ma si può sostenere la campagna anche con soli 5 euro. Con cifre più sostanziose si avrà diritto ad accessori, gadget e oggetti da collezione, come un vinile illustrato. Tanti i nomi coinvolti, tra cui cito brevemente Manuele Fior, Giacomo Nanni, Marino Neri, Anna Deflorian, Alessandro Ripane. La direzione artistica è come sempre di Francesca Protopapa, fondatrice della fanzine Squame, mentre la consulenza musicale è di Luc Frelon, dj e cultore del vinile.

Per approfondire i dettagli del crowdfunding e contribuire alla pubblicazione del volume potete andare qui. Per sbirciare nel Rock Motel e leggere le interviste agli artisti vi rimando al Tumblr del progetto. A seguire alcune illustrazioni in anteprima. Buona visione e… buon ascolto.

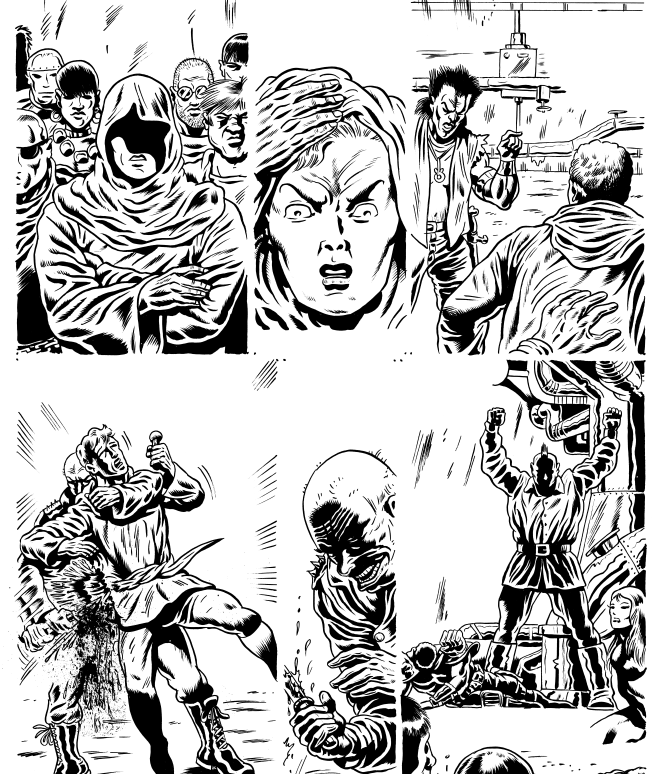

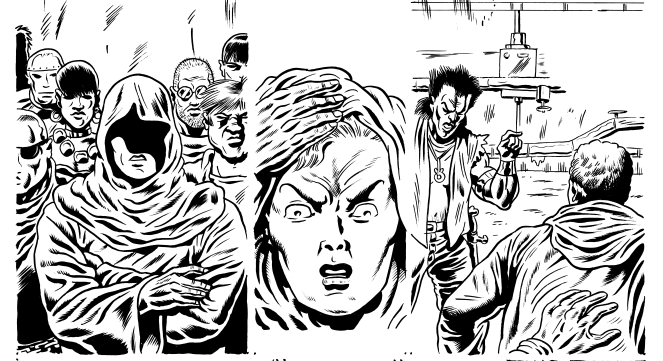

L’ultimo lavoro del grande Herb Trimpe

Herb Trimpe è stato uno dei disegnatori più importanti della Marvel degli anni ’70, famoso soprattutto per la sua lunga run su The Incredible Hulk. Trimpe ci ha lasciato lo scorso 13 aprile, mentre stava ultimando le matite di una storia per una nuova linea di fumetti chiamata All Time Comics, ideata dal newyorkese Josh Bayer, editor dell’antologia autoprodotta Suspect Device e autore di fumetti underground come Raw Power e Theth. Bayer è un grande fan dei fumetti Marvel di trenta o quaranta anni fa e ha ideato tra le altre cose numerosi bootleg di Rom, personaggio che in Italia ben conosciamo per la sua pubblicazione sulla storica antologia All American Comics edita dalla Comic Art. Le sue storie con protagonisti i cartoonist del Marvel Bullpen sono state spesso un’occasione per farci vedere l’uomo dietro l’artista, oltreché per denunciare il modus operandi della Marvel nei confronti di autori come Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko e Steve Gerber. Alcune scene dei suoi fumetti vedono Steve Ditko urlare “La Marvel e la Disney… sono il governo!” e una ragazza circondata da Deathlok, U.S. Agent, Howard The Duck e altri personaggi Marvel minori che dice “Facciamocene una ragione, qui siamo superflue come i disegnatori, gli inchiostratori e gli scrittori che hanno dato vita all’industria della Marvel Comics”.

Bayer di recente ha ricordato così Herb Trimpe sulla sua pagina Tumblr:

“L’anno scorso ho contattato Herb Trimpe e gli ho chiesto di disegnare una storia per una linea di fumetti che sto scrivendo ed editando. Eravamo in grado di offrirgli una tariffa decente e incredibilmente ha detto di sì, così che tra qualche mese pubblicherò quello che, a quanto ne so, è il suo ultimo fumetto. Il lavoro di Trimpe era dappertutto quando ero ragazzo, nei comic-book che uscivano e nelle ristampe, e i suoi personaggi fumettosi, spavaldi, monolitici, fluidi ma anche un po’ traballanti rappresentavano in pieno quella che era la mia idea di fumetto. […] Mentre mi arrivavano le mail con i suoi disegni l’anno scorso, ero rincuorato che a settant’anni stesse facendo uno dei suoi migliori lavori di sempre, pieno dei passaggi, delle luci e dello storytelling per cui era conosciuto. “Te lo devo dire, me la sto spassando… Era da parecchio tempo a questa parte che non facevo qualcosa di così divertente”, mi ha scritto, e io ne ero felicissimo. Ero contento per giorni ogni volta che lo sentivo. Continuavo a guardare il suo lavoro. Le linee erano sicure e potenti, il suo storytelling era ricco di quel tipo di inventiva che è il risultato delle migliaia e migliaia di pagine che aveva disegnato prima che entrassimo in contatto. Per me, avere l’approvazione sua o di altri professionisti come Rick Parker e Al Milgrom, ha significato avere tutto ciò che volevo dai fumetti, un cerchio senza fine tra passato e futuro. Soltanto in un’industria strana come questa qualcuno nella mia posizione, al livello più basso della piramide, può coinvolgere in un suo progetto artisti con anni e anni di esperienza e riconoscimenti alle spalle”.

Per il testo completo vi rimando alla versione inglese di questo post. Tutte le immagini sono tratte da Crime Destroyer Giant Size di Josh Bayer, Herb Trimpe e Benjamin Marra, in uscita a ottobre 2015.

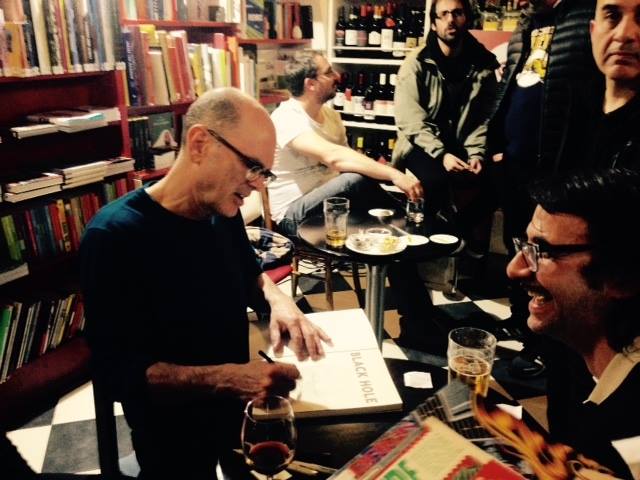

Una serata con Charles Burns

Giovedì 19 marzo la Libreria Giufà di Roma ha ospitato un incontro con Charles Burns, cartoonist statunitense che non ha bisogno di presentazioni. Burns, che i più conosceranno per la serie Black Hole, è arrivato a Roma per accompagnare la moglie Susan Moore, artista e insegnante di pittura, proprio come successe negli anni Ottanta, quando la coppia passò un paio di anni in Italia e Burns si unì al gruppo Valvoline. Più che un amarcord, la serata è stata l’occasione per far conoscere l’artista al pubblico romano, approfondendo il suo processo creativo e i temi dei suoi fumetti. A condurre la chiacchierata lo scrittore Francesco Pacifico, che fungeva anche da traduttore, mentre a occuparsi delle domande e delle digressioni sull’arte di Burns erano il critico di fumetti ed editor di Castelvecchi Alessio Trabacchini e il ben noto fumettista italiano Ratigher. Alla fine dell’incontro Burns si è trattenuto per ore a parlare con i lettori firmando dediche e soprattutto disegnando sketch, mostrando una disponibilità e una cordialità esemplari.

Alessio Trabacchini: Charles Burns è importante perché è un autore che sa raccontare la complessità. Ha trovato una forma narrativa e un segno per raccontare le ambivalenze, dei sentimenti, delle cose, del mondo. Vorrei chiedergli come è riuscito a raccontare un aspetto che nei fumetti è molto difficile da rendere, che è quello relativo al sesso, alla sessualità, alla bellezza e al desiderio. Penso che qui quasi tutti conosciamo le opere di Burns e lo associamo a qualcosa di molto estremo, o all’abiezione o a qualcosa di perverso: è vero a metà, perché in realtà Burns ha saputo raccontare benissimo la parte migliore dei sentimenti. Nelle opere di Burns e in particolare in Black Hole ci sono alcune delle rappresentazioni migliori del sesso che si possono trovare nei fumetti. E quindi vorrei domandargli qual è il suo approccio a questo aspetto della vita umana e alla sua rappresentazione.

Charles Burns: Quando sono riuscito a sentirmi a mio agio nell’esprimere qualcosa di veramente personale, ho voluto farlo cercando di essere il più possibile libero e aperto. La sessualità è nella vita di tutti, ma io non volevo fare qualcosa di totalmente gratuito o pornografico. Volevo che il sesso fosse una parte naturale della storia. In Black Hole per esempio ci sono delle scene molto forti ma la storia nel complesso non è gratuita, non è fatta per provocare o titillare il lettore. Mi piace l’idea di mettere in una storia di tre-quattrocento pagine dieci pagine focalizzate su qualcosa di molto forte, ma non di più. Ci sono stati dei momenti, mentre scrivevo, in cui pensavo “non so se la gente vuole vedere questo”. Pensavo che la mia visione delle cose fosse troppo cupa ma volevo allo stesso tempo essere più onesto e aperto possibile. All’inizio non ne ero molto consapevole, ma nelle mie prime opere mi sono abbastanza censurato, avevo delle idee che erano molto forti e forse disturbanti ma mi trattenevo dall’esprimerle. Ho cercato in tutti i modi di superare quel blocco, di fare qualcosa di forte e onesto… Comunque non ho mai incontrato una donna con la coda…

Ratigher: La mia prima domanda è simile ma su un altro aspetto. Io considero Burns il fumettista che più ha saputo raccontare l’occulto, il bizzarro. Se nel cinema c’è Lynch, nel fumetto c’è Burns, sono loro i custodi del mistero, dell’incubo, di tutto un mondo onirico e oscuro. Io immagino che lui abbia iniziato perché era attratto probabilmente dalle storiacce, dalle situazioni malsane, però visto il livello che ha raggiunto gli voglio chiedere se c’è stata una sorta di evoluzione tipo quella dei giochi di ruolo, cioè se da occultista, da amante delle cose bizzarre e oscure, senta di avere il potere di uno stregone, di poter far paura alle persone, di poter fare dei libri che abbiano delle forze oscure dentro.

Burns: Per qualche ragione le mie storie si muovono verso l’oscurità, ma io non voglio spaventare intenzionalmente qualcuno. Sin da piccolo sono stato attratto da un lato oscuro dell’America, un lato nascosto della cultura americana. C’è una facciata in cui tutto sembra a posto, ma sotto a questa c’è a volte un lato oscuro e nascosto. Sono stato sempre interessato a questa facciata e a ciò che rappresenta. Ed ero interessato anche alla realtà, la realtà in cui sono cresciuto, la realtà che sentivo mia e che non aveva niente a che fare con lo status quo e con la visione normale di una famiglia sicura e felice. Nessuna delle mie storie è molto felice.

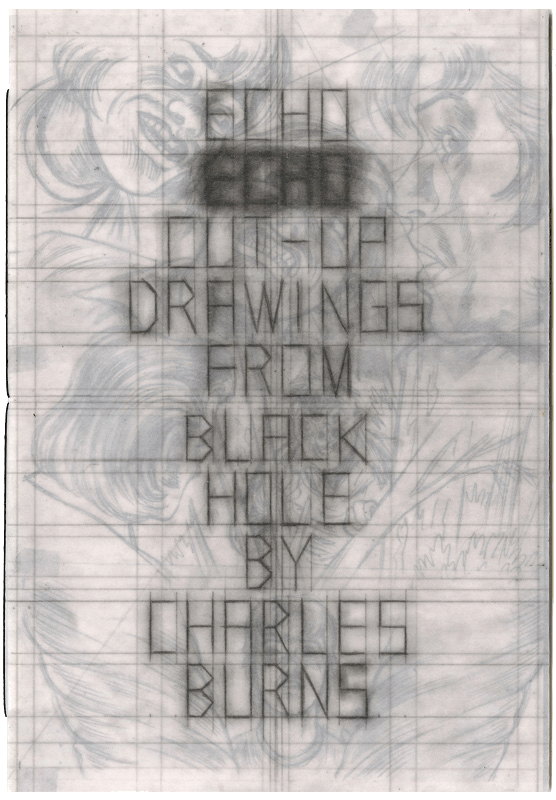

Trabacchini: Un’altra cosa che volevo chiedere riguardava la linea. Ovviamente questo c’entra con il modo di raccontare che dicevo prima, perché per un autore di fumetti la prima scelta di stile per decidere come vuole raccontare è decidere il tipo di segno che utilizzerà. Il segno di Burns che conosciamo è netto, molto netto, con contrasti molto forti di bianco e nero, lo è diventato sempre di più nel corso degli anni ma era già abbastanza definito sin dall’inizio. Nonostante ci siano le ombre, questa è in qualche maniera una sua versione della linea chiara francese, un richiamo che nell’ultima trilogia diventa esplicito, perché c’è un mondo onirico in questi tre libri che è una sorta di mash-up fra la Tangeri di William Burroughs e Il Cairo che Hergé racconta ne Il granchio d’oro come scenario delle avventure di Tin Tin. Stavo riguardando poi questa cosa qua (mostra Echo Echo, una raccolta degli schizzi preliminari di Black Hole, ndr), che è interessante perché si capisce qual è il modo di arrivare alla linea chiara, cioè a partire da disegni che sono comunque un groviglio di segni, di incroci di linee, dove tutto è molto forte, molto istintivo, e questi disegni diventano quel segno di Black Hole che è così controllato da rimanere coerente, omogeneo per un’opera che è durata dieci anni. In realtà guardando le matite di Tin Tin sono molto simili, sono piene di segni, di linee incrociate, per arrivare a qualcosa di chiaro e preciso. E quindi è così che penso che la linea riesce a trattenere tante inquietudini, tante tensioni. Mi piacerebbe che ci parlasse di come si arriva a quel segno.

Burns: Credo che lo stile del mio lavoro emuli lo stile americano degli anni Cinquanta e Sessanta. Sin dall’inizio mi sono ispirato a Harvey Kurtzman, a Mad Magazine e a quelle meravigliose linee molto scure che si vedevano all’epoca. D’altro canto mi piacevano le splendide linee chiare di Hergé, il che è piuttosto insolito per un americano della mia generazione. Comunque rispetto alla linea chiara francese, il mio stile è più per una linea scura e spessa ottenuta con l’uso del pennello. Mi è stato fatto notare che anche Hergé quando disegnava aveva una linea molto grezza, molto aperta, che poi veniva distillata e distillata fino a diventare questa linea più specifica. Il libro che hai mostrato è una collezione di disegni preliminari, alcuni sono più puliti, altri più grezzi, molto gestuali. Partono da un’idea molto legata al gesto di disegnare e poi si raffinano via via che lavoro.

Ratigher: Anche io rimango su una domanda tecnica, ma che poi tecnica non sarà. Da fumettista in erba la cosa del lavoro di Burns che mi ha cambiato il modo di vedere i fumetti è stato il fatto che il suo disegno molto tecnico, che piace tanto e lo fa amare da un gran numero di persone, sia sempre un disegno in ogni vignetta narrativo. Anche nelle illustrazioni, quando disegna il volto di una persona, tu ti immagini la vita di quella persona, non è mai un disegno fermo e non è mai un disegno fatto per dare sfoggio della sua tecnica. Ogni pagina è molto studiata, con i bianchi e i neri perfetti, però ogni vignetta racconta sempre un pezzo di storia, non c’è un piacere fine a se stesso nel disegno. Quindi volevo chiedere se questa cosa è vera, se lo rispecchia e come ci ha lavorato.

Ratigher: Anche io rimango su una domanda tecnica, ma che poi tecnica non sarà. Da fumettista in erba la cosa del lavoro di Burns che mi ha cambiato il modo di vedere i fumetti è stato il fatto che il suo disegno molto tecnico, che piace tanto e lo fa amare da un gran numero di persone, sia sempre un disegno in ogni vignetta narrativo. Anche nelle illustrazioni, quando disegna il volto di una persona, tu ti immagini la vita di quella persona, non è mai un disegno fermo e non è mai un disegno fatto per dare sfoggio della sua tecnica. Ogni pagina è molto studiata, con i bianchi e i neri perfetti, però ogni vignetta racconta sempre un pezzo di storia, non c’è un piacere fine a se stesso nel disegno. Quindi volevo chiedere se questa cosa è vera, se lo rispecchia e come ci ha lavorato.

Burns: Per me il fumetto è tutto incentrato sulla storia. So che la gente guarda il mio lavoro e dice “guarda questa linea”, “guarda quanto è bravo a disegnare”, ma dal mio punto di vista la storia è sempre l’elemento più importante. Raccontare la storia è un processo di distillazione continua, si inizia da una bozza e poi le idee e il lavoro vengono pian piano rifiniti. Ci sono momenti in cui voglio disegnare una bella immagine, ma se non è parte della storia non ci entra.

Ratigher: Ma è una cosa innata? Perché vista da fuori, ogni vignetta è disegnata in maniera eccelsa, però continua a essere narrativa, anche nelle sue storie vecchie. Voglio sapere se lui ci ha ragionato, perché l’alchimia è quasi solo sua, qui ci sono un sacco di lettori di fumetti e chiedo anche a loro se ci sono disegnatori così tecnici e al tempo stesso narrativi, a me viene in mente tra i grandi americani soltanto Robert Crumb, che ha un controllo del disegno sempre bello, sempre ricco ma sempre devoto alla storia. Quindi voglio sapere se per lui è stato uno sforzo oppure se ha culo e gli è venuto da quando è nato.

Burns: Io sono nato con… niente (in italiano, ndr). Credo che si siano dei cartoonist che partono da un aspetto visuale e altri che partono dall’aspetto letterario. Io ho cominciato dall’aspetto visuale e poi ho dovuto insegnare a me stesso il linguaggio dei fumetti per poter raccontare una storia. Quest’anno compirò sessant’anni e non ho ancora ben capito come si fa, ma comunque ci provo. Quando le parole e le immagini si combinano perfettamente, le immagini diventano invisibili. Il lettore si trova nel mondo della storia e non pensa più alla tecnica con cui è stata realizzata, non pensa “oh, che splendido disegno”… E’ immerso. E’ la stessa cosa che succede con i bei film o con i bei romanzi, con qualsiasi cosa. La tecnica diventa invisibile.

Pacifico: A questo punto ti chiedo se puoi darci degli esempi di film e romanzi in cui la tecnica è diventata invisibile. A me per esempio viene in mente l’ultimo film di Paul Thomas Anderson, Inherent Vice, in cui sembra che lui abbia cercato di proposito di cancellare tutta l’idea di un regista che fa le grandi scene per farci sentire solo la storia.

Burns: Per me è sempre impossibile indicare con precisione le cose che mi hanno influenzato. Potrei citare dei fumetti in particolare di cui mi piacciono la tecnica, la linea, l’aspetto, ma in realtà sono stato influenzato un po’ da tutto. Io cerco di fare del mio meglio per raccontare la mia storia, non la storia di Ernest Hemingway o di Nabokov o di Murakami.

Ratigher: Quello che volevo sapere io, riallacciandomi alla domanda di prima, è sapere se Burns a volte si siede e fa un disegno che non sia un fumetto, che non sia narrativo. Se gli capita mai che magari gli piace un fiore e decide di disegnarlo.

Burns: Mi piacerebbe farlo, ma no. Sfortunatamente il mio è un processo lentissimo. Per esempio, il mio amico Chris Ware mi ha raccontato che lui ha questo grande foglio di carta bianca, si mette seduto e inizia a disegnare. Questo per me è impossibile, io ho appunti su appunti e foglietti con piccoli disegni, schizzi, bozze. Il mio processo non è assolutamente naturale, è lento ed elaborato. Penso che la mia vita sarebbe molto più semplice se avessi un approccio più diretto ma non è possibile.

Valerio Bindi (fumettista italiano e curatore del Crack! Festival): Stavo già accennando prima a Burns quello che penso del suo lavoro, cioè che lui è profondo nella struttura della storia, che ha sempre molti livelli – il richiamo agli anni Cinquanta e Sessanta, l’adolescenza, il bosco, le metafore, i luoghi oscuri – e poi è invece quasi superficiale nel disegno e questa superficialità dà a questo mondo uno sguardo molto ampio. C’era questa riflessione che faceva Deleuze su Lewis Carroll, in cui diceva che Lewis Carroll è ampio e non è profondo. Burns usa tutte e due le armi e in questo modo ha un segno molto affascinante. Per la mia generazione lui non è il disegnatore dell’inquieto e dell’oscuro ma il disegnatore che ha portato le tematiche anni Cinquanta verso il mondo dell’underground. Io e il mio gruppo di disegnatori che negli anni Novanta cominciavano a fare fumetti, come il Professor Bad Trip, trovavamo in lui una rilettura dei racconti dell’underground in una chiave fredda, sintetica e chiara che era proprio il nostro sentire degli anni Ottanta e Novanta. Adesso però mi sembra che l’underground si sia spostato, mi sembra che il movimento dell’underground nel fumetto in questo momento parli europeo, mi sembra che l’America sia in qualche modo seguendo le nostre cose. Volevo sapere che cosa ne pensa lui, se vede un underground oggi e se sì dove lo vede.

Burns: L’undergound per me significava avere tredici-quattordici anni e scoprire Robert Crumb e i fumetti che guardavano oltre il mondo commerciale, in cui gli autori cercavano di esprimere se stessi. All’inizio i fumetti underground dovevano essere per forza trasgressivi, perché essere underground voleva dire occuparsi di sesso, droga, politica. Adesso è diverso, perché ormai è dato per scontato che chiunque può scrivere qualcosa di veramente personale senza doversi preoccupare di appartenere a un genere predefinito… Non so se il mondo dei fumetti underground è mai esistito realmente. L’underground sembra un qualcosa di difficilmente accessibile, ma da ragazzino mi bastava semplicemente salire su un autobus e andare in un negozio per comprare Zap, i fumetti di Crumb o qualsiasi fumetto hippy e più tardi punk. Mi piace l’idea che qualche ventenne non sappia chi è Robert Crumb o chi sono io e che guardi a qualcosa di nuovo, muovendosi in altre direzioni. Non c’è nessun bisogno di conoscere i classici. Non sono interessato ai giovani artisti che citano continuamente le loro influenze. E’ un piacere quando le cose vanno avanti, progrediscono. Anni fa ricordo che il mio caro amico Art Spiegelman mi disse che noi dovevamo superare Will Eisner, guardare oltre. L’underground è un ragazzo di diciassette, diciotto, diciannove o anche vent’anni che non ha mai sentito parlare di me.

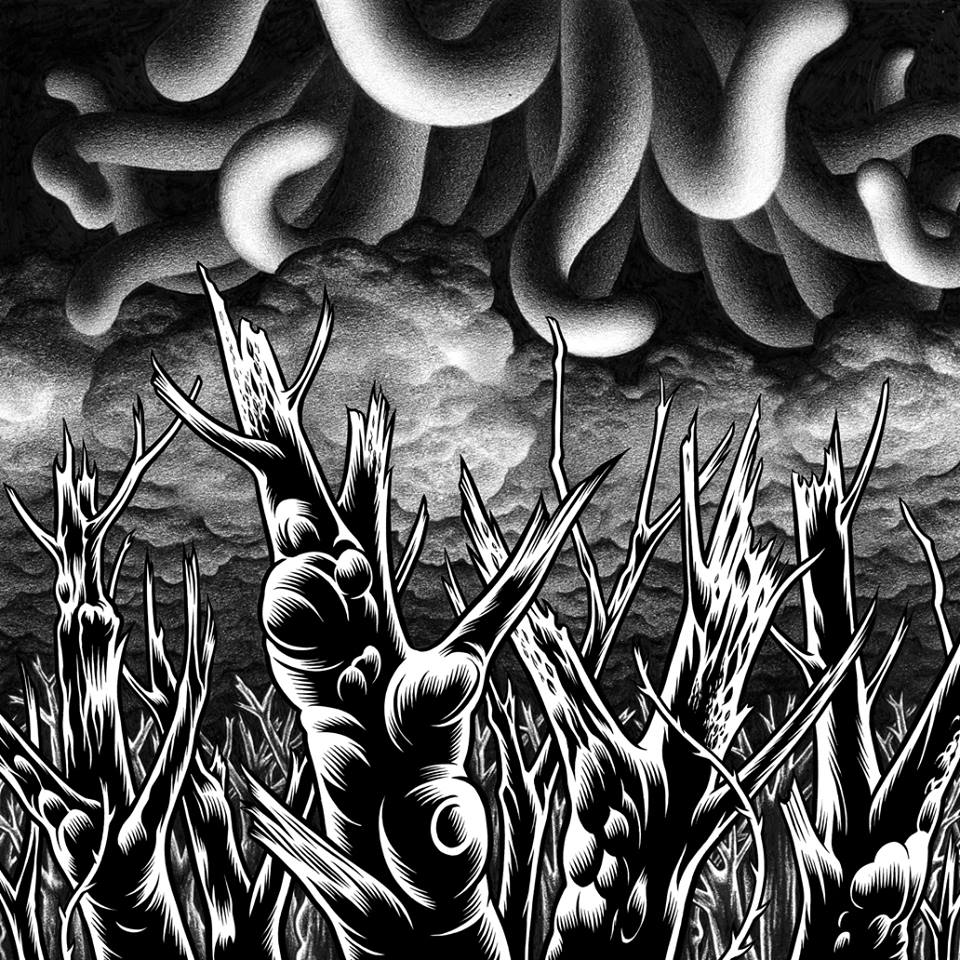

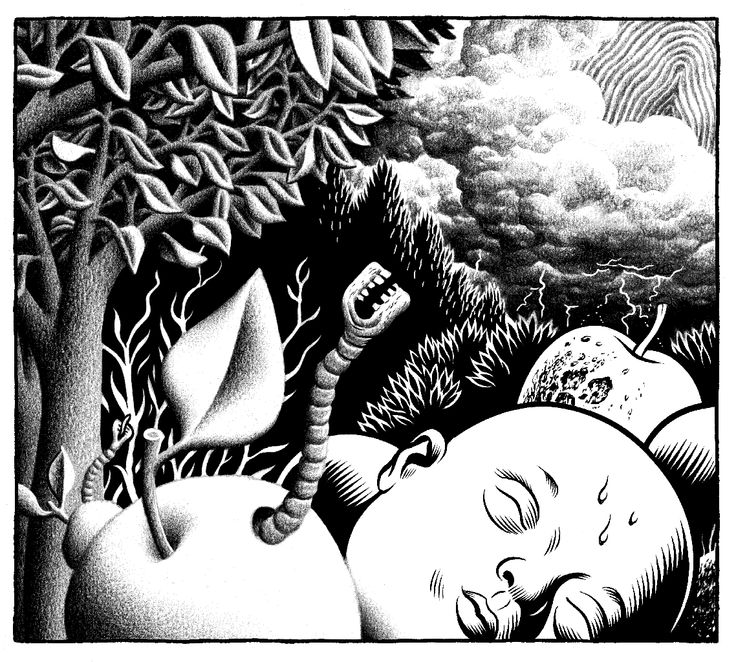

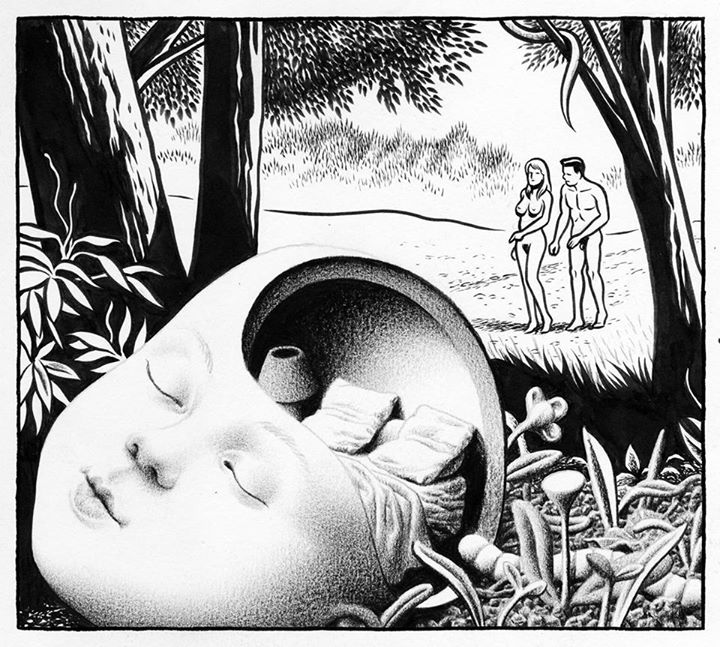

“In the Garden of Evil”: un’anteprima

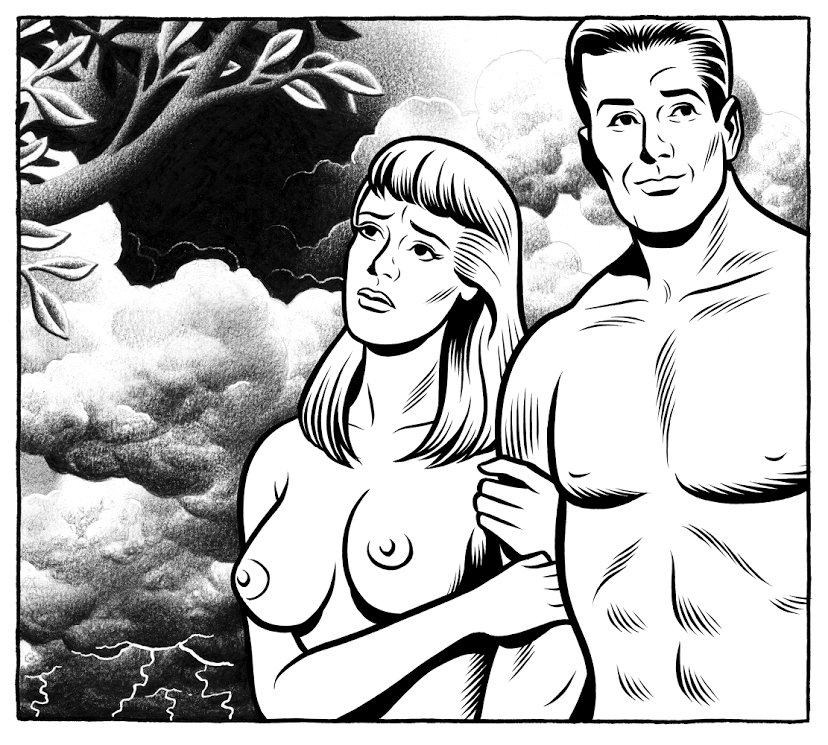

Nell’ottavo numero di Mon Lapin, rivista pubblicata dai francesi de L’Association, Patrice Killoffer chiamava a raccolta fumettisti come Philippe Druillet, Ludovic Debeurme e Lorenzo Mattotti, dando vita a collaborazioni a quattro, sei o anche otto mani poi protagoniste di una mostra presso la Galerie Anne Barrault di Parigi. Tema principale dei lavori di Mon Lapin era il bosco e tra gli artisti coinvolti non poteva dunque mancare Charles Burns, che con Killoffer realizzava una serie di disegni ispirati al tema del Giardino dell’Eden e intitolati In the Garden of Evil. Adesso la Pigeon Press di Alvin Buenaventura raccoglie questa collaborazione tra due maestri del fumetto contemporaneo in un art-book rilegato a mano di 28 pagine in formato quadrato (7.25 x 7.25 pollici, ossia 18.42 centimetri per lato). Stampato in 1000 esemplari numerati e firmati dai due autori, il volume conterrà anche un 7″ flexi-disc con una canzone inedita di Will Oldham, cantautore statunitense conosciuto sotto una vasta schiera di pseudonimi (Palace Brothers e Bonnie Prince Billy i più noti). In the Garden of Evil debutterà al Toronto Comics Art Festival del 9 e 10 maggio prossimi, alla presenza dei due autori. Subito dopo verranno messe in vendita on line 200 copie, a un prezzo ancora da definire.

Per ora l’unica immagine ufficiale rilasciata dalla Pigeon Press è quella di apertura, ma suppongo che nel volume ci saranno tutti i disegni visti su Mon Lapin, come quelli che potete vedere nel reportage dalla mostra alla galleria Barrault di Le Blog de Shige e quelli in basso, trovati qua e là sul web.

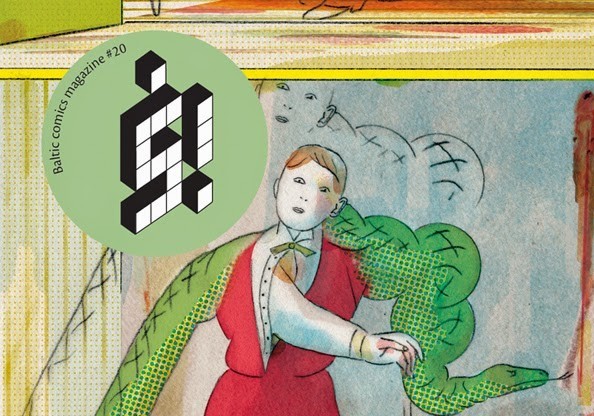

Viaggio nel fumetto portoghese – š! #20

Dopo l’ottavo numero realizzato esclusivamente da cartoonist finlandesi, l’antologia lettone š! torna a dedicare un’intera uscita ad autori di una sola nazione, mettendo insieme con l’aiuto del guest editor Marcos Farrajota del collettivo Chili Come Carne una serie di fumetti realizzati da autori portoghesi e incentrati sul tema dell’inquietudine, ispirato dal Livro do Desassossego di Fernando Pessoa. L’aderenza al tema e il suo sviluppo sono mutevoli ed eterogenee, ma questa non è certo una novità per š!, pubblicazione che numero dopo numero ci ricorda cosa si può fare con il fumetto, mostrando i tanti approcci possibili al medium e al suo linguaggio. Ci sono così artisti come Amanda Baeza, Filipe Abranches e Paulo Monteiro che lavorano su una griglia prefissata di vignette, altri come Rafael Gouveia e Daniel Lima che adattano rispettivamente i testi letterari di Bernardo Soares e Paul Ableman, mentre Cátia Serrão e João Fazenda giocano con spazio, forma, colori e Bruno Borges crea una storia partendo da una serie di scarabocchi.

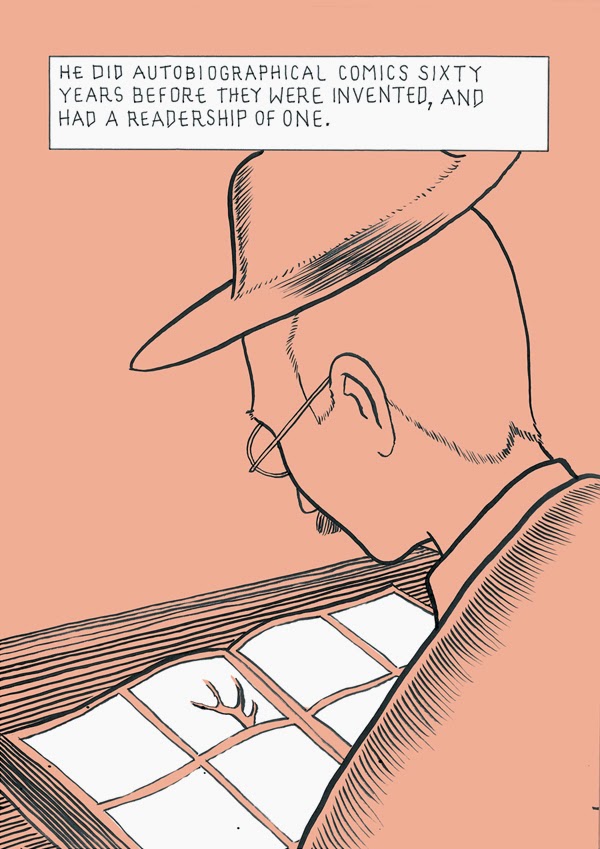

La vignetta non è la regola nelle pagine di š! e infatti troviamo fumetti costruiti con illustrazioni a tutta pagina o anche con fotografie, come nel caso dei contributi di Tiago Casanova e Joana Estrela. In particolare le sei pagine della venticinquenne Estrela sono una delle cose migliori dell’antologia, dato che combinano brillantemente immagini tratte da un film anni Cinquanta con un testo incentrato sull’inquietudine del giovane cartoonist dei nostri tempi, tra ritratto sociologico e parodia. La Estrela è tra gli autori più giovani della raccolta, mentre il titolo di veterano spetta a Tiago Manuel, autore di una serie di notevoli illustrazioni narrative che ricordano stilisticamente vecchi libri di medicina. Manuel è anche un personaggio tipicamente portoghese, in grado con i suoi oltre 25 progetti eteronimi di poter rivaleggiare con lo stesso Pessoa. L’ombra di Pessoa si avverte in parecchi di questi fumetti e soprattutto in quello di Francisco Sousa Lobo. L’autore della graphic novel The Dying Draughtsman delinea la figura di Fausto M. Fernandes, un misterioso pioniere del fumetto lusitano. Probabilmente è questo il miglior contributo del lotto, dato che centra perfettamente il tema dell’inquietudine ritraendo un protagonista problematico, è poetico senza essere retorico, suscita domande sull’autobiografia e la natura stessa dell’arte.

Arrivati alla fine del volumetto abbiamo un’idea più chiara del panorama fumettistico portoghese, o forse non ne abbiamo idea… D’altronde come potrebbero due sorelle cilene che vivono a Lisbona (Amanda e Milena Baeza), una scienziato sociale precario con una linea accattivante (Daniel Lopes), un fotografo (Tiago Casanova) e una studiosa di linguistica (Cátia Serrão) creare uno stile condiviso? Ci sono un sacco di “lupi solitari” da queste parti – come Marcos Farrajota fa notare nel saggio introduttivo – e forse è questa la bellezza dei fumetti portoghesi e del fumetto indie in generale. Così, più che essere una visione d’insieme di una scena, questo numero di š! è la storia dinamica di un medium in una nazione. O è anche, se preferite, il racconto di una lotta, quella fatta dal fumetto per uscire fuori dalle stanze, dalle case e dagli studi degli autori per arrivare faticosamente ma gioiosamente tra le mani dei lettori.