“From Now On” with Malachi Ward

Malachi Ward is the creator of Ritual, a series published by Revival House Press, and the author of From Now On, a collection of short stories which is coming in June from Alternative Comics. He also collaborated with Matt Sheean at the series Expansion and at some issues of Brandon Graham’s Prophet. The interview that follows took place at the end of May via e-mail.

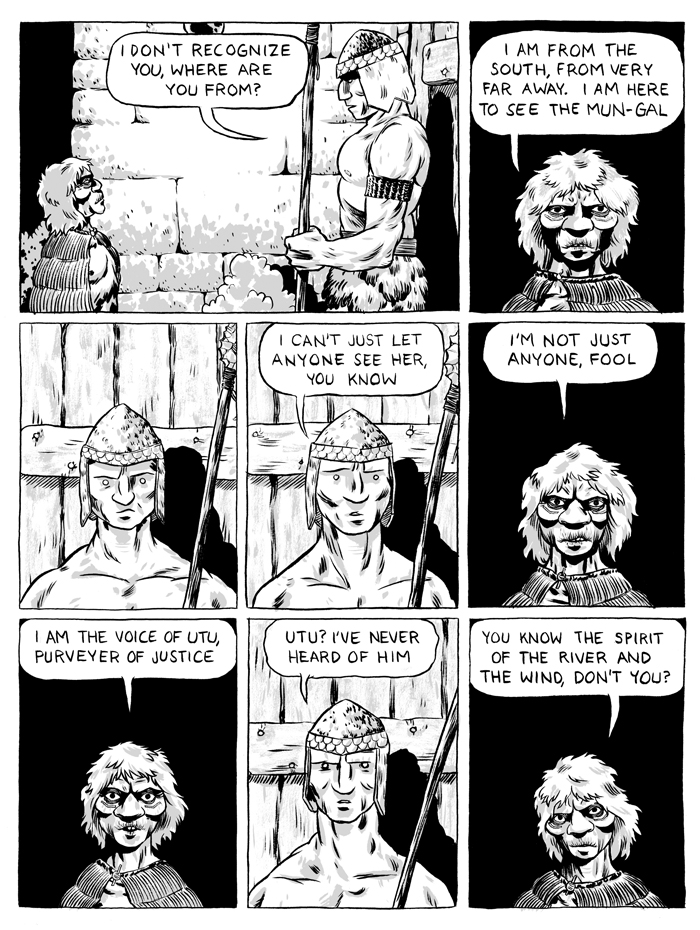

Since you talked about your formation as a comic artist and your inspirations in this interview with Dave Nuss, I’d like to begin this chat with some questions about From Now On. This is your first “book” and I think it would be nice to introduce it to the readers. I saw the summary and the very first story will be Utu, a sort of classic in your production, in fact it’s one of the first comics or exactly the first comic you printed. Do you think that self-publishing Utu in 2009 could be considered as a key moment in your career?

After college I was reading a lot more comics, and flirting with the idea of making them. Of course, “comics” can be almost anything, and I didn’t have much of an idea about what I wanted to do. My art at the time was kind of… whimsical I suppose? Anyway, throughout 2007-09 I kind of honed in on what I wanted to do. I started Utu in 2009, and traded off working on that and The Scout, for Jordan Shiveley’s Hive anthology. I finished them both in time for APE 2009. So both were a big breakthrough for me. It was the first work that I finished and was ok printing up and presenting to the world. I still kinda like those stories too.

I think Utu is a really original story, because it starts in a way and then moves in a completely different direction. And it has a lot of different registers, in the beginning it seems a sort of mythological tale, then it becomes funny and in the end it’s also sad in some way. I’d like to know if you started it with the intention to use different atmospheres and genres, or if the plot came out as a natural process.

One of the appeals to me of Utu was that bifurcation in the plot – that it feels like it’s one kind of story and then quickly becomes a totally different one. I’m not really into plot “twists”, but who doesn’t like a story surprising them, so long as it all fits? I’m drawn to that narrative device a lot… It’s something I often try to insert into a story, even if it doesn’t work! Each of the Ritual stories kind of has an element of that to varying degrees.

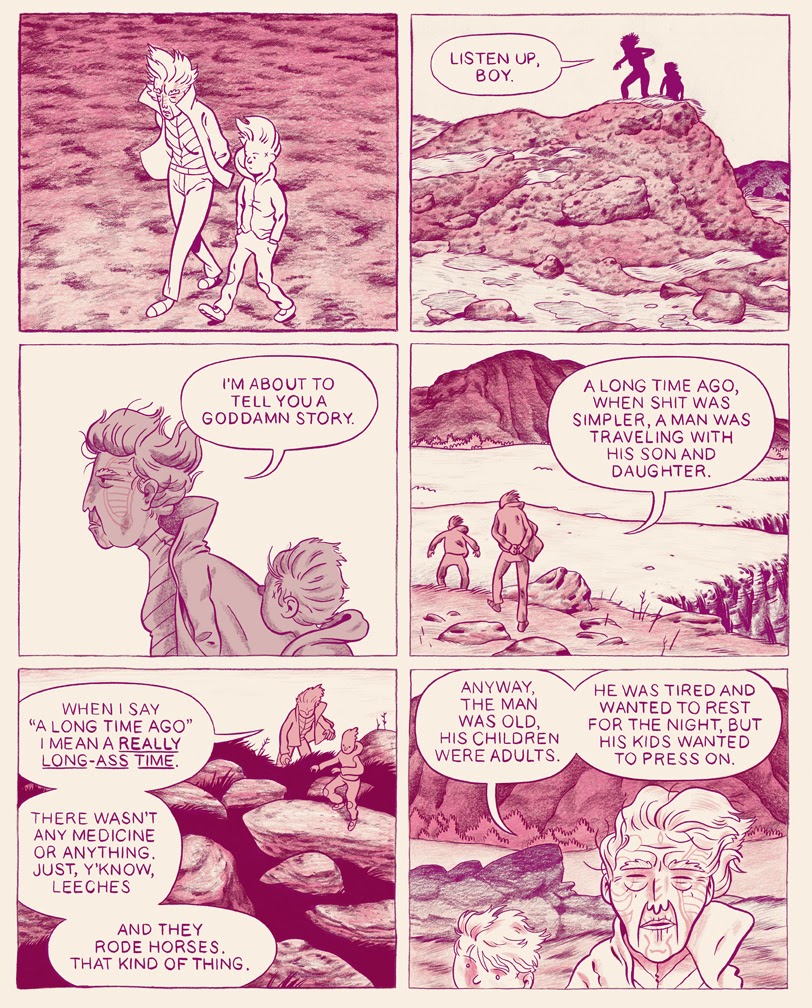

Before you mentioned The Scout, another story from 2009 that will be in From Now On, where you examined the concepts of time and repetition. This comic is based on a fixed grid of six panels per page and, watching your old things, you used a rigid structure several times. On the other hand, your recent work is based on a less regular layout. Do you think this could reflect your improvements as a cartoonist or it’s only a coincidence?

For The Scout, I was concerned with telling the story in as few pages as possible (since it was for an anthology with limited space) while still making it read naturally and not seem too compressed. I think keeping a regular panel layout like the one in The Scout helps with that. I did the same thing for another story in From Now On called Henix for similar reasons. I also think that the 6-panel layout just works well for a 5.5″x8″ mini-comic. While I certainly think I’ve progressed in my comics skills, I would still return to a rigid panel layout like that if it suited the comic. Even when my comics have a lot of varying panel sizes and arrangements, they usually follow regular tier breakdowns that I don’t deviate from.

Another comic in From Now On is Top Five, a sort of metanarrative sci-fi story about Star Trek, definitely an inspiration for you. Sweet Dreams and The Oviraptor are also reinterpretations of some science fiction stereotypes. I think this is what makes your comics fresh and original, that you use some ideas taken from sci-fi movies and tv series but you treat them in your own way, creating a mix that isn’t so widespread in the world of alternative comics at the moment…

Sometimes, for me, a story starts with me thinking about how I might handle a genre trope. I think the goal is to find the core of whatever that idea is, the emotional element that clicks, the thematic or atmospheric qualities that could register with the reader, and then to work out from there while avoiding all the typical pratfalls a science fiction/fantasy/horror story can fall into.

Besides the ones we talked until now, I haven’t read the other stories in From Now On. Can you introduce them or some of them to the readers?

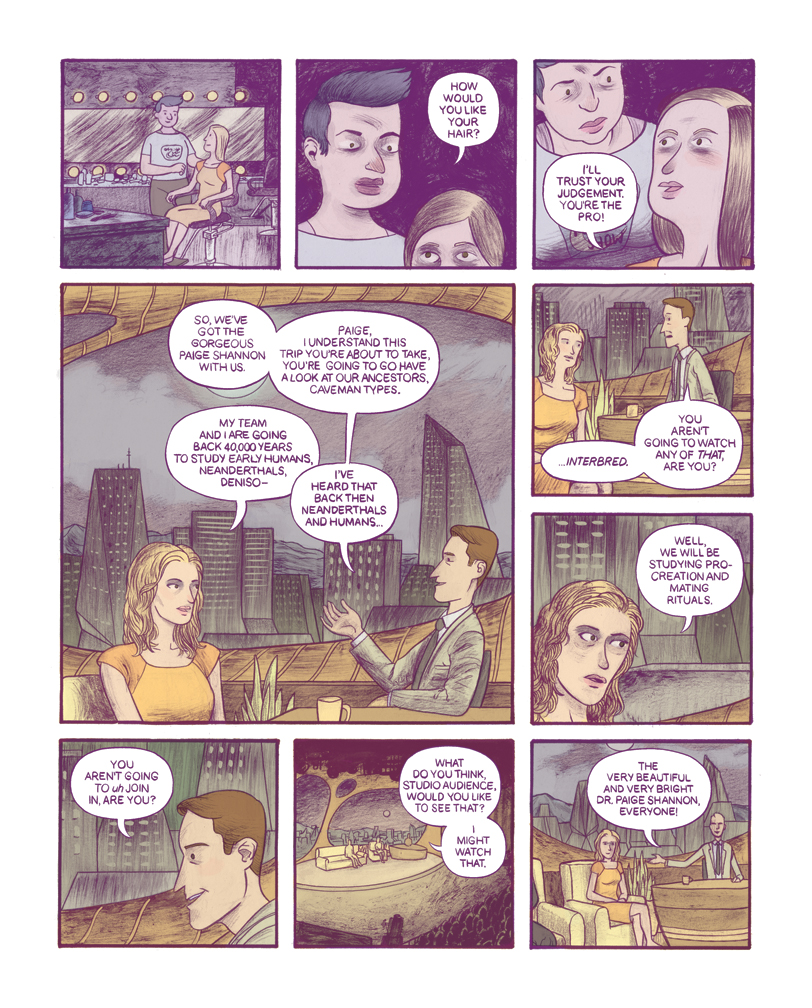

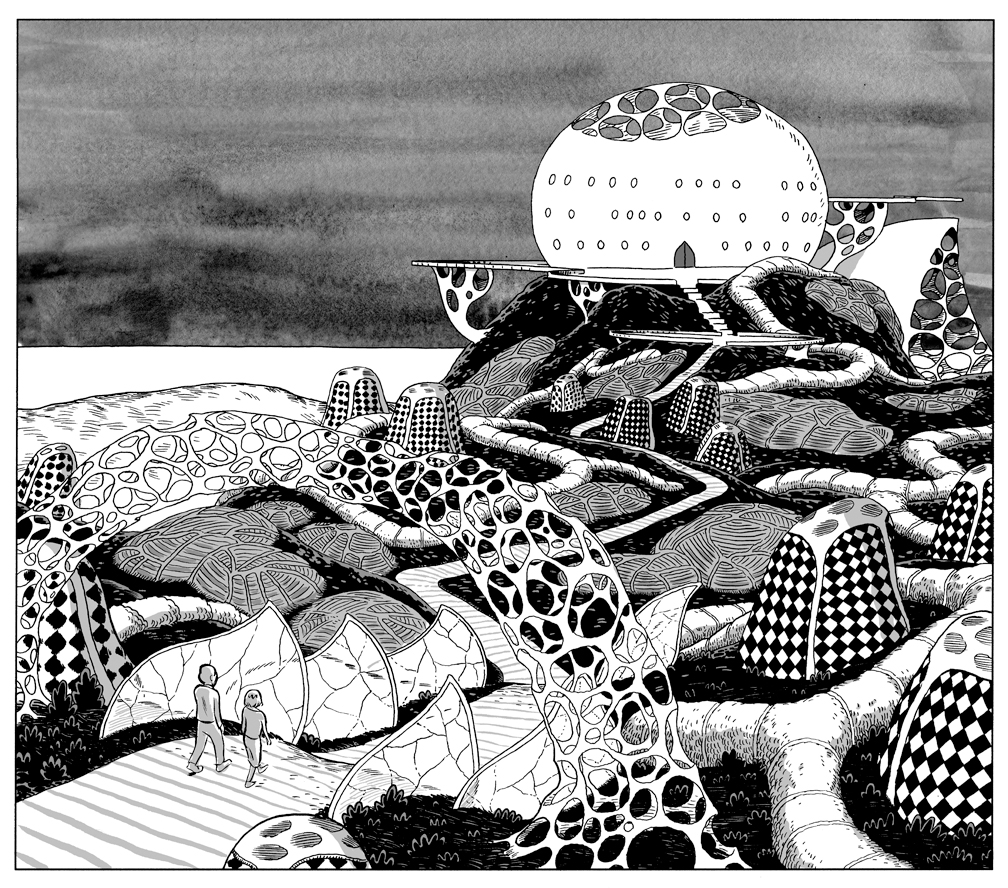

There’s a new full color comic called Disconnect (a preview page below, editor’s note), which takes place in the same world as Top Five, The Oviraptor, and Hero of Science. It follows one of the other characters that disappeared when the team jumped back in time. Some other stories include Beasts of Kay-7, which is sort of my take on a Star Trek type of a team that is exploring a new planet inhabited by mysterious monsters. Henix, which I mentioned earlier, is a high-fantasy kind of a story about a deformed (to the eyes of the main characters) prisoner with secrets about the royal family.

Let’s talk about Ritual now, the series published by Revival House Press, where every issue is a stand-alone story of 20-30 pages. Before picking up Ritual #2 – The Reverie, I had seen your work only online and when I read that story I was shocked… It was fucking good! Then I read others of your comics and I noticed that The Reverie is probably the most “serious” and touching comic you’ve made until now. And unlike the other issues of Ritual, this one follows a very linear narrative. I’d like to know how you came to tell this story, if it moves from your fears or from some nightmare you had.

Because The Reverie centers around a family death, it certainly contains a lot more emotionally potent situations than in my other work. Something like the death of a family member is frequently used as a cheap motivation for a main character, so I tried to be careful to imbue the build up and fallout from that event with as much empathy as possible. The idea for the story came from my fascination with the range of behavior a single person is capable of, and how opportunity shapes our ability to act in a moral way. It also deals with some notions of regret – I’ve heard people talk about what they should’ve done with their lives, or how they think things should’ve gone. It’s always been a profoundly alien feeling to me, something I have trouble understanding. It’s an idea that I’ll very likely explore with more depth in the future.

In The Reverie your drawing style seems less controlled and defined than usual. This is not a bad thing to me, because I think in some sequences you did a beautiful work depicting the landscapes or the rage of the main character. I think maybe you were doing some experimentation…

The first half of that comic, I think, is still pretty controlled. Everything that takes place outside of the titular dimension is inked with a brush and pretty carefully drawn. I actually didn’t have much time while I was working on the book, and most of the second half was drawn over the course of a couple weeks. I knew that I wanted to change the style a bit inside the wish dimension, like inking with a pen instead of a brush, but because of the limited time that part of the story also took on a much looser quality.

Ritual #1 – Real Life and Ritual #3 – Vile Decay are quite similar in the structure, while for the contents Real Life is – as the title tells itself – a true life story turning out in a very frightful way and Vile Decay is about future and how people are fucking up the world. As a whole this series talks about a lot of big themes, as family, relationships, death and – in issue three – also politics and ecology. But I think all three issues of Ritual so far are mostly talking about your fears. Or this is the way I see it…

My starting point for the Ritual series is that it’s a horror anthology. Really, I only think Real Life ended up feeling anything like something one would identify as part of the horror genre, but every entry is certainly related to fear in a fundamental way. Real Life is inspired by actual nightmares: my wife hatefully abandoning me, and me turning “evil”. The Reverie kind of spins out from that, I was thinking about how easily I could succumb to being a pretty scummy person if the right situations presented themselves. Vile Decay, while ostensibly about the degradation of society, was more about my fear that I’ll completely disconnect from the world as I grow older and it becomes easier to do so.

Another way to read Ritual #1 and #3 is as pilots of a tv series, but your comics will never have a follow-up, so the reader has to imagine it or try to interpret the stories browsing through the pages…

Ritual #3 has an especially elusive narrative quality to it… it could be a very unsatisfying read for a lot of people. I think there’s enough in that one that a person can unpack if they think it’s worth it, so hopefully the comics invite the ready to do that. In the next group of comics I’m making I’m kind of reacting to that (something I tend to do for whatever reason) and creating stories that have much more definitive resolutions.

In this group of comics there is also Ritual #4?

I’ve got a pretty detailed outline that I’m really excited about. Right now it’s just about finding time in my schedule to actually draw it. Ritual #4 is tentatively titled The Left Hand Path.

So it could be about your fear of becoming left-handed…

How’d you know??? That’s my real deepest fear.

Do you think the new issue will use two colors as the previous? I loved the pinks and the oranges of Vile Decay, they contributed to create a nebulous and unreal setting.

I think Dave Nuss and I are planning for Ritual #4 to be printed in full color, but it will retain a limited palette.

I know you are working on a couple of new projects with your friend Matt Sheean, with whom you already collaborated for Expansion and for Brandon Graham’s Prophet. I know you and Matt are totally sharing the different tasks of the creative process and I’m curious how you’re doing this.

For the project we’re currently working on (Ancestor, which’ll be part of the Island anthology for Image) Matt and I break the work down like this: We both talk through the plot of each issue and come up with an outline, usually together. If the outline calls for any important chunks of dialogue, we each take a sequence and write it out. Then, over the course of a couple intense days, we do thumbnails for the whole issue. From there Matt pencils, I ink and do flat colors, and Matt adds lighting effects to the colors. I then letter the final page.

This is a very interesting way to develop a collaboration… Ancestor will be a long story?

Ancestor will end up being longer than anything I’ve done in awhile, probably about 120 pages when it’s done.

Besides Ancestor are you working on other long stories or you’ll going on with short ones?

Currently I’m thumbnailing a full color comic that’ll be around 80 pages. I’m planning to do mostly longer stories from this point forward.

I’d like to conclude talking about what is exciting you at the moment, if you’re listening to some music in particular, or if there is a comic or a novel or a movie you enjoyed a lot recently…

I just reread the Lawrence Wright book Going Clear and I’m pretty obsessed with it. I’m doing some research about Indo-European culture that’s really interesting. In the comics world I thought Jillian Tamaki’s Sex Coven story for Frontier was really inspiring and fantastic. Same goes for the newest issue of Crickets by Sammy Harkham. I haven’t seen many movies I really loved this year, but I really liked Ex Machina, and I thought Mad Max: Fury Road was a lot of fun. I’ve been listening to the 1988 album Encounter by Michael Stearns while I write, as well as a lot of Jean-Michel Jarre.

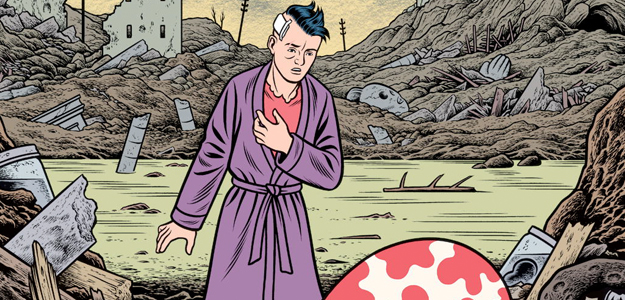

Dylan Horrocks e la penna ritrovata

A breve distanza dall’incontro con Charles Burns, di cui potete leggere qui, la Libreria Giufà di Roma ha ospitato lo scorso venerdì 22 maggio un altro fumettista di fama internazionale, il neozelandese Dylan Horrocks, che i più ricorderanno come l’autore dell’indimenticabile Hicksville. La tappa romana ha concluso una serie di quattro incontri in cui Horrocks ha presentato in Italia la sua nuova fatica, Sam Zabel e la penna magica, uscito da qualche mese per i tipi di Bao Publishing, dialogando con fumettisti italiani come Zerocalcare, Vanna Vinci e, proprio nell’occasione di venerdì 22, Roberto Recchioni. A presentare i diversi appuntamenti Michele Foschini di Bao, che faceva anche da interprete. Di seguito la trascrizione integrale della chiacchierata. Buona lettura.

Michele Foschini: Questo libro esce dopo diciassette anni dal precedente lavoro lungo di Dylan, Hicksville, che alcuni avranno letto nell’edizione Black Velvet e che un giorno Bao ripubblicherà. Lascio subito la parola a Roberto per le domande.

Roberto Recchioni: Partiamo subito con un argomento che hai appena toccato, la lunga pausa tra Hicksville e il nuovo libro. Diciassette anni sono tanti anche per gli standard di Axl Rose quando fa Chinese Democracy… Che cosa è successo in mezzo?

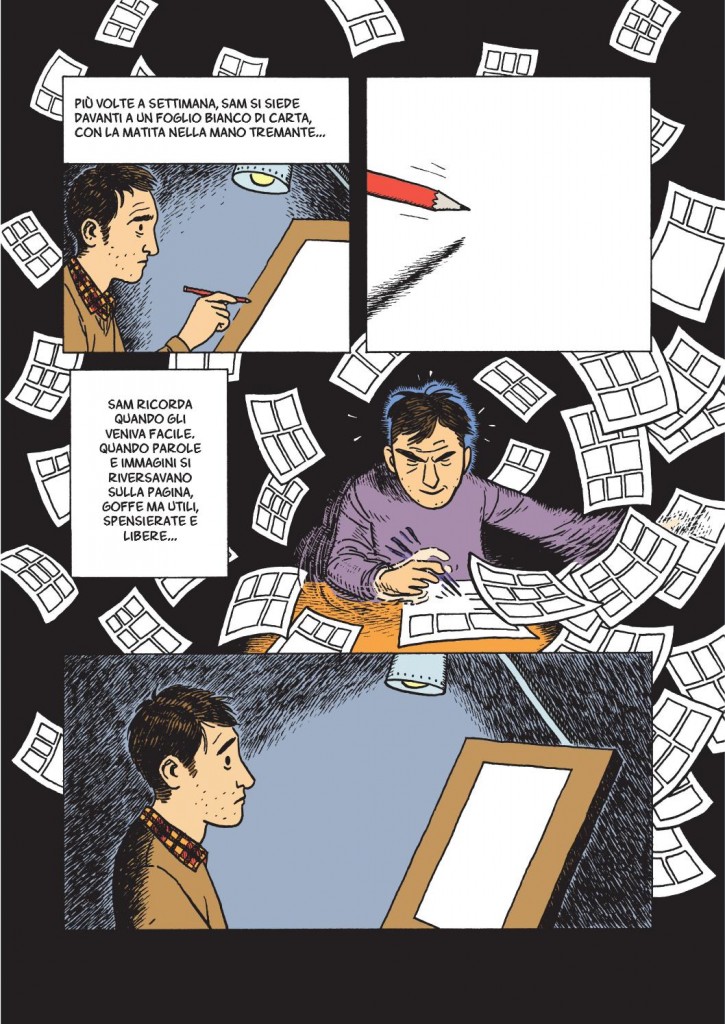

Dylan Horrocks: Ho perso le mie penne… Non sapevo dove erano finite e ci ho messo un sacco di tempo a ritrovarle… Beh, seriamente quello che è successo è che ho perso la mia fede nelle storie e nei fumetti. Quando uscì Hicksville ebbe più successo di quello che mi aspettavo, non economicamente perché non mi ha fatto fare molti soldi, ma di critica, perché ha avuto delle recensioni veramente buone ed è stato oggetto di tesi di laurea. In qualche modo l’idea di iniziare un nuovo libro dopo Hicksville mi intimidiva. Inoltre mi sono posto alcuni problemi, perché innanzitutto volevo imparare a disegnare meglio, cosa che mi ha portato a guardare agli autori che mi piacevano, e poi volevo cercare di scrivere una storia che fosse artisticamente e contenutisticamente più profonda di Hicksville. Tutto ciò mi ha in qualche modo prosciugato, al punto che mi sono bloccato completamente. La salvezza è arrivata sotto forma di un lavoro per la Dc Comics e così per quattro anni ho scritto dei comic-book mensili per la Dc (Batgirl e Hunter: The Age of Magic, ndr), una cosa positiva perché mi ha salvato dalla bancarotta totale, anche se in realtà scrivevo delle storie in cui non credevo, che non erano il mio genere. Da quel momento ho cominciato a interrogarmi sul significato delle storie, mi chiedevo cioè se le storie potessero essere utili o se fossero soltanto delle bugie, che distorcevano la realtà e il nostro modo di essere. A quel punto non riuscivo più non solo a disegnare i fumetti, ma non avevo neanche più la forza di leggerli, come non riuscivo nemmeno a leggere i romanzi e a vedere i film. Era come se avessi perso la mia fede nelle storie.

Recchioni: Leggendo il romanzo, la prima parte sembra quasi la riproduzione letterale di ciò che ti è successo. Il protagonista è un fumettista che ha scritto un primo romanzo di successo, è molti anni che non ne fa un secondo e sta scrivendo una brutta serie di supereroi con una supereroina che mena alla gente ma che ha alle spalle un passato glorioso. Il libro è un esercizio di cura o un esercizio di analisi? Hai cercato di capire la situazione o hai cercato di curarti da quello che ti stava succedendo?

Horrocks: Beh, quando ho iniziato il libro stavo cercando di trovare un’uscita dalla trappola in cui ero caduto ma non sapevo come fare. Penso che il libro sia tutte e due le cose, perché mi volevo curare ma non sapevo qual era la medicina, di cosa avessi veramente bisogno. Sapevo qual era il problema e così ho creato una situazione per il mio personaggio simile al problema che stavo vivendo e l’ho esplorata, in un certo senso ho cercato di capire cosa avrebbe fatto il personaggio. E penso che questo mi abbia aiutato a trovare una via d’uscita. Alla fine ha funzionato…

Recchioni: Una cosa che ho notato nel libro, e l’ho notata in un senso un po’ critico, è che alla fine il tuo personaggio trova una via d’uscita ma la trova guardando a un passato che è molto dorato, i fumetti precedenti al sistema, quelli della golden age, una realtà diversa da quella attuale. E’ tutto molto incantato e attraverso questa visione più pura e più ingenua del mondo dei fumetti e delle storie ritrova la sua vena, ritrova se stesso. E’ davvero così, dobbiamo così tanto guardare a un passato che forse nemmeno esiste realmente?

Horrocks: Nel mio primo libro, Hicksville, una delle cose che ho fatto è stata immaginare nuove strade per il fumetto immaginando un nuovo passato. Hicksville presenta una storia immaginaria del fumetto, una serie di eventi che in realtà non sono mai successi ma che in qualche modo io volevo che fossero successi. Pensavo, se quello fosse il nostro passato, immagina i fumetti che potremmo creare ora… Con La penna magica mi sono sentito abbastanza intrappolato dal passato dei fumetti e anche dal presente. Il libro esplora la storia del fumetto ma introduce anche un personaggio, Alice, che è realmente il futuro dei fumetti, lei è quella che salva la situazione ogni volta, che ogni volta è così coraggiosa da tentare qualcosa di nuovo. La penna magica parla in realtà del futuro del fumetto e questo è piuttosto chiaro sin dall’inizio della storia… Ma non voglio anticipare troppo… Comunque ho un profondo rispetto per la storia del fumetto, anche per quei fumetti con cui ho dei problemi, che riflettono una visione del mondo sessista o in genere molto ristretta. Anche lì c’è qualcosa di magico da cui possiamo attingere e spero che questo filtri dalla mia storia.

Recchioni: Oltre che di magia io parlerei proprio di ingenuità, di una purezza che sembra il cuore portante della storia…

Horrocks: Sì, al cuore del libro c’è una domanda, che mi stava tormentando quando l’ho iniziato… Siamo moralmente responsabili per le nostre fantasie? E’ importante ciò su cui fantastichiamo? E penso di non avere una risposta a questa domanda ma la conclusione a cui sono giunto è che abbiamo la responsabilità di essere onesti, onesti a proposito delle nostre fantasie, dei nostri desideri, delle nostre paure e anche delle cose che ci danno semplicemente piacere… Mi rendo conto che da lettore le storie che amo veramente sono quelle che danno la sensazione di provenire da un luogo interiore, non quelle che vengono create perché la gente pagherà per leggerle o perché la gente si aspetta di leggerle o quelle che semplicemente ci eviteranno di finire nei guai, ma quelle di cui ci importa veramente.

Recchioni: Da italiano leggendo il libro ho sentito forte il tema del senso di colpa, della responsabilità rispetto alle nostre fantasie. Il libro è molto solare ma ha anche un forte conflitto all’interno del personaggio, che vive un costante dilemma morale a proposito delle sue fantasie, quelle che vorrebbe vivere come uomo, le fantasie sessuali… Vorrei chiederti qual è stata la tua formazione religiosa perché sembri quasi un cristiano per il senso di colpa che si percepisce…

Horrocks: A dire il vero sono stato cresciuto da degli hippy intellettuali che negli anni ’60 facevano parte di una cellula trotskista rivoluzionaria americana… (risate) Erano anche poeti, che hanno scelto il mio nome sia per Bob Dylan che per Dylan Thomas e che hanno chiamato mia sorella ispirandosi a Simone de Beauvoir. Così sono cresciuto senza alcuna educazione religiosa ma con un fortissimo senso di responsabilità personale, politica ed etica. Mio padre era un grande appassionato di fumetti e insegnava cinema, così ho potuto leggere Robert Crumb quando avevo solo dieci anni e più o meno alla stessa età ho visto Ultimo tango a Parigi, perché mio padre ne doveva parlare a scuola e lo ha portato a casa proiettandolo su una parete la sera prima della lezione per prendere appunti… Mi ricordo che lo vidi e pensai “ma cosa starà facendo con quel burro?”. Quindi sono cresciuto in un contesto molto liberale ma è anche vero che sono stato adolescente negli anni ’80, un periodo in cui la gente era molto coinvolta nella politica e si discuteva di argomenti importanti, come la pornografia… Io avevo sedici anni e ovviamente mi piaceva abbastanza la pornografia ma mi sentivo anche in colpa per questo e non a causa della morale cristiana ma per le politiche femministe. Sono cresciuto con dei genitori femministi e sembra strano definirmi femminista da uomo ma era come mi consideravo io e la discussione sulla pornografia mi metteva seriamente in difficoltà… Avevo volumi di Milo Manara nella mia libreria… E mi piacevano non poco…

Foschini: Sì, ne abbiamo parlato anche troppo l’altra notte… (risate)

Horrocks: Personalmente mi sono interrogato su questi argomenti per trent’anni ma di recente il dibattito su come vengono trattati i temi di genere è tornato di estrema attualità nel mondo dei fumetti anglofono. La penna magica inizia con due citazioni, una del poeta Yeats che dice “Nei sogni iniziano le responsabilità”, l’altra di Nina Hartley – una performer americana, produttrice di porno, che riesce a parlare con intelligenza di pornografia – che dice “Il desiderio non ha morale”… Ho voluto che il libro iniziasse con queste due citazioni, perché penso che siano vere entrambe anche se sono completamente contraddittorie. E mi interessava esplorare lo spazio tra le due affermazioni, per cercare di comprendere perché io le ritengo entrambe vere…

Recchioni: Rimango sulla sessualità perché secondo me è un tema molto importante nel libro… Abbiamo due situazioni in particolare, una che riguarda delle donne che vengono violentate dai cattivi e si ribellano, ma poi decidono che tutto sommato gli piaceva e quindi fanno la pace, così che iniziano a farlo in modo consenziente e ricomincia una sorta di gioco… Quel tipo di fantasia delle donne inseguite dagli alieni, tipica degli anni ’50, viene alla fine vista con uno sguardo gentile, mentre dall’altro lato il cattivo è l’hentai, il fumetto porno giapponese, che invece è visto sotto un aspetto prettamente negativo.

Horrocks: Una delle cose che mi interessano è come possiamo utilizzare e interpretare in modi diversi anche le fantasie che troviamo moralmente problematiche. Mi è capitato di sentirmi attratto da arte che esprimeva idee veramente orribili, ma magari stava esprimendo un’ossessione o una fantasia che è potente, che ha un valore… Uno degli elementi centrali del mio libro è che alcuni fumetti presenti all’interno della storia sono reali, il personaggio li disegna con una speciale penna magica e quindi quando i personaggi ci entrano trovano altri personaggi reali, che stanno compiendo delle azioni vere e proprie. Uno dei personaggi del fumetto viene da una di queste storie che vengono visitate e non le piace per niente dove sta andando la trama, anche perché riesce a vedere cosa sta per succedere. Una delle mie intenzioni con il libro era anche quella di esplorare la relazione tra i personaggi e l’autore, perché io certe volte mi sento in qualche modo responsabile per i miei personaggi e così ho cercato di salvare questa ragazza da quella situazione che riecheggia certi manga, perché lei non è assolutamente contenta di ciò che gli sta capitando. Ogni volta che nel libro sta arrivando a una risposta semplice, a dire “questo è giusto” o “questo è sbagliato”, qualcosa sconvolge questa convinzione. Nello stesso modo, anche nella storia di ispirazione manga, ci sono scene che mi dava fastidio immaginare, ma le ho disegnate comunque perché volevo esplorare non solo i turbamenti morali ma anche i piaceri che possono derivare dalle fantasie. E in generale credo che quando si parla di fantasie erotiche ed etica, non si può avere una conversazione seria e onesta se non si parla anche della gioia e dei piaceri legati all’erotismo. E anche quel personaggio che non vuole essere la vittima della fantasia manga mostra un comportamento ambivalente… Conosco parecchie persone che hanno delle forti fantasie ma che non vorrebbero averle, e io volevo parlare proprio di cosa facciamo delle nostre fantasie, se le abbracciamo o se cerchiamo di sopprimerle…

Recchioni: Oppure le possiamo vivere…

Horrocks: Beh… (risate). Credo che la differenza tra disegnare una fantasia e viverla nella vita reale sia enorme. Negli ultimi mesi, da gennaio in poi, dopo gli eventi di Charlie Hebdo, c’è stato un intenso dibattito a proposito del potere dei disegni, e la domanda che ci si è posti è se certe cose debbano essere disegnate o meno… E durante questa discussione ci sono delle frasi che ho sentito spesso da persone diverse, “questi disegni fanno del male alla gente”, “questi disegni sono violenti”. E la cosa che mi ha disturbato è che molte persone stanno perdendo la distinzione tra le sensazioni che provi quando guardi un disegno e la vera violenza fisica. E questo è veramente fastidioso, è una cosa che non riesco a concepire e che mi fa pensare che ci stiamo muovendo in un territorio molto pericoloso…

Foschini: A questo punto il tempo è quasi finito, quindi lascerei spazio alle domande dal pubblico.

Recchioni: Ne vorrei prima fare un’ultima io, per concludere… Alla fine del libro sembra che ti sei riconciliato con te stesso, che hai trovato le tue penne…

Horrocks: Sì, erano sotto alla scrivania, prima o poi dovevo guardarci, no?! (risate) Più o meno a metà del libro mi sono reso conto che mi stavo divertendo disegnando un fumetto più di quanto avessi mai fatto in vita mia… Quindi sotto questo punto di vista l’atto di guarigione sicuramente ha funzionato.

Recchioni: Infatti il libro a un certo punto sembra proprio un atto di piacere, è un libro fatto con piacere e questo piacere traspare…

Horrocks: Beh, grazie! Per me è stato un viaggio di esplorazione, di scoperta, perché non sapevo quale fosse la medicina o la cura ma ne avevo bisogno. E hai ragione, parte di quello che ho trovato è stato il piacere, il piacere di raccontare una storia, il piacere di disegnare, il piacere della fantasia erotica… Ho riscoperto tutte queste cose e sono riuscito a metterle al centro di ciò che stavo facendo e penso che questo sia stato importante, significativo e profondo… E cazzo, è stato veramente divertente!

Dal pubblico: Non so quanto sarà contento della domanda, ma io volevo chiedere se questo processo di guarigione lo porterà a proseguire Atlas, che è il lavoro che ha interrotto da qualche anno a questa parte…

Horrocks: Vuole sapere di Atlas, vero? (risate) Mi piace la tua t-shirt degli Yo La Tengo… Beh, Atlas era una serie che ho iniziato dopo Hicksville, veniva pubblicata nell’omonima rivista formato comic-book (l’antologico interamente realizzato da Horrocks per la Drawn and Quarterly, tre numeri pubblicati dal 2001 al 2006, ndr) e doveva essere la mia successiva graphic novel. Ma nel secondo numero cominciai a serializzare anche La penna magica, che iniziò come una storia secondaria e non doveva diventare una storia lunga, ma poi prese il sopravvento, divenne la storia che volevo veramente raccontare e così Atlas venne messa da parte… La stessa cosa successe con Hicksville, che iniziò come una storia secondaria in un mio magazine (Pickle, di cui sono usciti dieci numeri dal 1993 al 1997 per Black Eye Books, ndr) in cui serializzavo una graphic novel molto più seria che si chiamava Café Underground… E non ho mai completato nemmeno Café Underground, Hicksville ha preso il sopravvento, ha cominciato a ossessionarmi e l’ho dovuto finire…

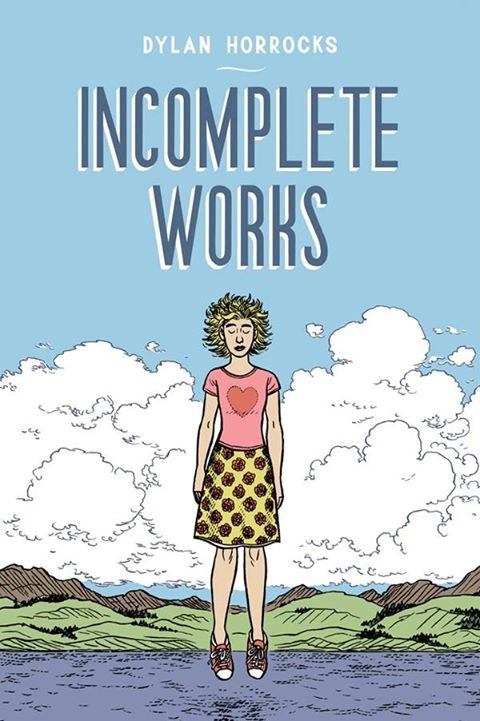

Foschini: A questo punto io dovrei tradurre il volume Incomplete Works (uscito l’anno scorso per la neozelandese Victoria University Press, ndr), così potete avere tutti questi pezzettini…

Horrocks: Ci sono un sacco di storie che ho iniziato ma non ho mai finito… Vorrei finire Atlas un giorno, ma non so quando succederà perché continuo a cambiare idea su dove deve andare la storia e altri progetti stanno prendendo la precedenza…

Dal pubblico: Potresti mettere Atlas come storia secondaria in una rivista, così la finirai sicuramente…

Horrocks: (risate) Questa è veramente una bella idea…

Dal pubblico: Io vorrei chiedere invece, partendo dal ruolo della web artist presente in questo libro, cosa ne pensa lui del fumetto web e come ritiene che il fumetto digitale influenzerà l’editoria…

Horrocks: Amo l’idea dei web comics, penso che sia veramente eccitante. Negli anni ’80, quando iniziai a disegnare seriamente fumetti, c’erano le macchine fotocopiatrici, erano economiche e ti permettevano di fare i tuoi fumetti in economia… Il mio primo fumetto è stato stampato negli uffici della scuola, ero veramente gentile con le segretarie e loro mi facevano usare la fotocopiatrice… Ed è così che ho iniziato a pubblicare i miei fumetti.

Recchioni: Anche io, stessa storia…

Horrocks: A scuola? Con le segretarie? (risate) Le segretarie sono gli eroi mai celebrati del fumetto! Comunque questo ha portato a una rivoluzione del fumetto, perché la gran parte dei cartoonist che sono emersi negli anni ’80 a Sydney, in Nuova Zelanda, oppure negli Stati Uniti, in Canada o in Inghilterra, vengono dalle fanzine fotocopiate… La rivoluzione non era soltanto avere tanta gente che faceva fumetti, ma avere nuove persone che facevano fumetti e tanti tipi di persone diverse che facevano i fumetti, c’è stata un’esplosione di diversità nelle voci che producevano fumetti… Internet è come questa rivoluzione ma mille volte più potente, è straordinario quello che sta succedendo, ci sono cartoonist da tutto il mondo, ognuno con il suo background, ognuno che fa un fumetto diverso dall’altro, un sacco di donne, cartoonist transgender, omosessuali, asessuali, di tutto… E per me questo è fantastico… Anche io ho iniziato a pubblicare Sam Zabel e la penna magica come un web comic, soprattutto perché volevo vedere cosa si provava…

Everything is ending “Here”

“Di tanto in tanto arriva un artista che prende il potenziale accumulato dalla sua disciplina e lo rielabora in nuovi modi di vedere e sentire. Cézanne ci è riuscito nella pittura, Stravinskij nella musica, Joyce nella scrittura – e penso che Richard McGuire lo abbia fatto con i fumetti”.

“Di tanto in tanto arriva un artista che prende il potenziale accumulato dalla sua disciplina e lo rielabora in nuovi modi di vedere e sentire. Cézanne ci è riuscito nella pittura, Stravinskij nella musica, Joyce nella scrittura – e penso che Richard McGuire lo abbia fatto con i fumetti”.

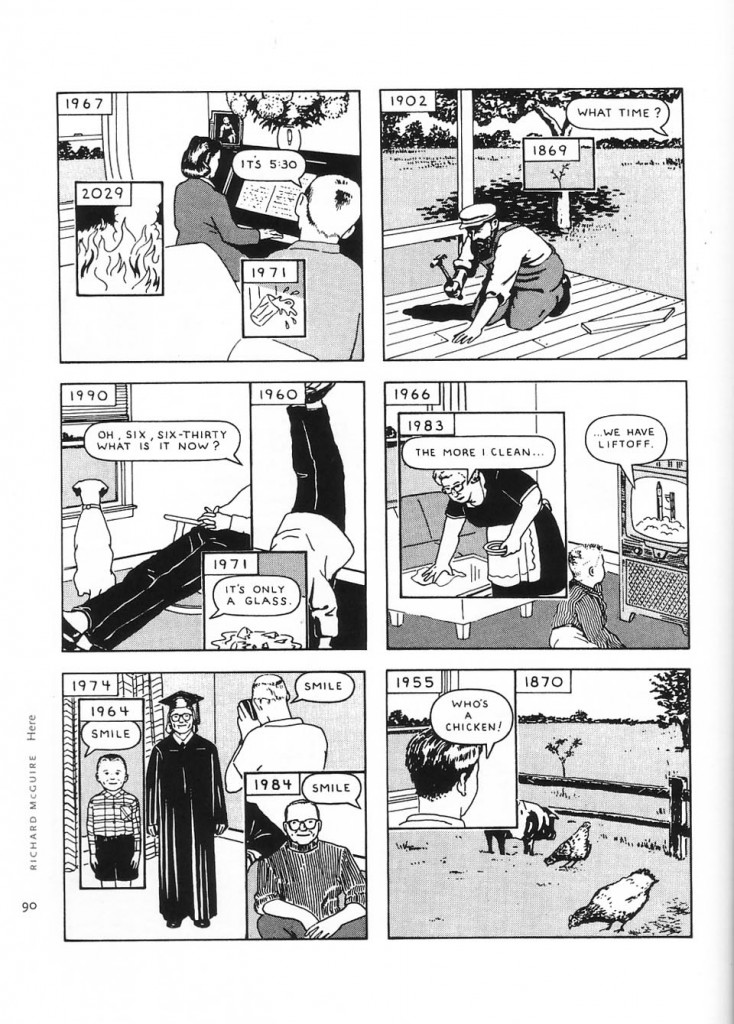

Basterebbe questa frase di Chris Ware per capire l’importanza della prima incarnazione di Here di Richard McGuire, una storia di 6 pagine apparsa nel 1989 in Raw vol. 2 #1 e che è possibile leggere qui. Era quello il famoso fumetto – rivoluzionario, stracitato, oggetto di saggi, convegni e persino di un cortometraggio – in cui l’artista statunitense – copertinista del New Yorker, bassista della band Liquid Liquid, autore di libri per bambini e film d’animazione, grafico e altro ancora – raccontava con un approccio estetico essenziale la storia di un angolo di mondo in diversi momenti storici, definiti di volta in volta da una data. Ma la caratteristica principale di Here erano le finestre che apparivano e si affastellavano creando il caos nelle sei ordinate vignette di ogni pagina, dando vita a passaggi temporali repentini che portavano il lettore a spostarsi in meno di un batter d’occhio dalla preistoria al futuro, mostrandoci per lo più l’angolo di una stanza ma a volte anche cosa c’era e cosa ci sarà in quell’angolo, come uno scenario lavico nel 500.957.406-073 a.C., l’edificio ancora in costruzione nel 1902, pompieri che spengono un incendio nel 2029, una cerimonia all’aperto nel 2033.

“Avevo realizzato due strisce che erano state pubblicate poco prima di Here – ha raccontato McGuire in un’intervista a Thierry Smolderen pubblicata sull’ottavo numero di Comic Art del 2006, dove è stato ristampato anche il fumetto originale e dove è apparso il saggio di Ware citato in apertura – in un piccolo magazine chiamato Bad News, curato da Mark Newgarden e Paul Karasik. L’idea iniziale mi venne dall’appartamento in cui mi ero appena trasferito. Pensavo a chi aveva vissuto lì prima di me. Feci alcuni sketch di una pagina divisa in due parti verticali, dove sulla sinistra il tempo si muoveva avanti, mentre sulla destra si muoveva all’indietro. All’epoca, stavo frequentando delle lezioni tenute da Newgarden e Karasik sul fumetto (dopo una serie di conferenze di Spiegelman che avevo già seguito poco prima), e loro mi incoraggiarono ad andare oltre i semplici sketch per svilupparli in una storia. Un giorno ero in giro con un mio amico, Ken Claderia – con cui andavo a scuola e che adesso è uno scienziato che lavora per la Stanford University – e fu un suo commento che fece a proposito di Windows che mi portò a pensare che poteva trattarsi di una vista multipla piuttosto che di uno split screen. Fu quello il momento “eureka”. L’idea è basata su una concezione multi-dimensionale del tempo – nel pensare il tempo non come lineare, ma come se tutto il tempo esistesse simultaneamente. Volevo che lo spettatore pensasse all’immagine più ampia, al fatto che noi entriamo in contatto soltanto con una parte della realtà. I dinosauri stanno ancora camminando da qualche parte in questo spazio ma in un altro tempo”.

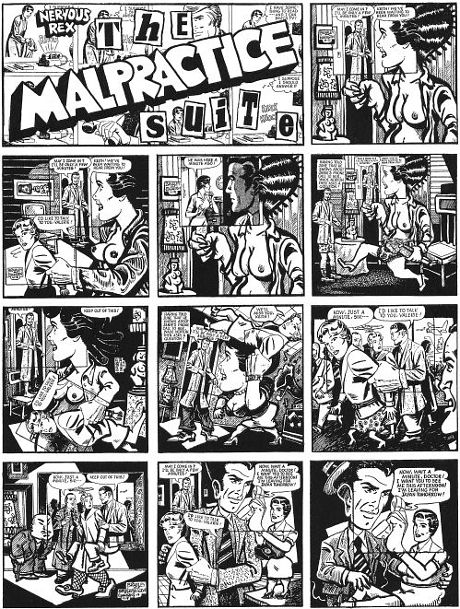

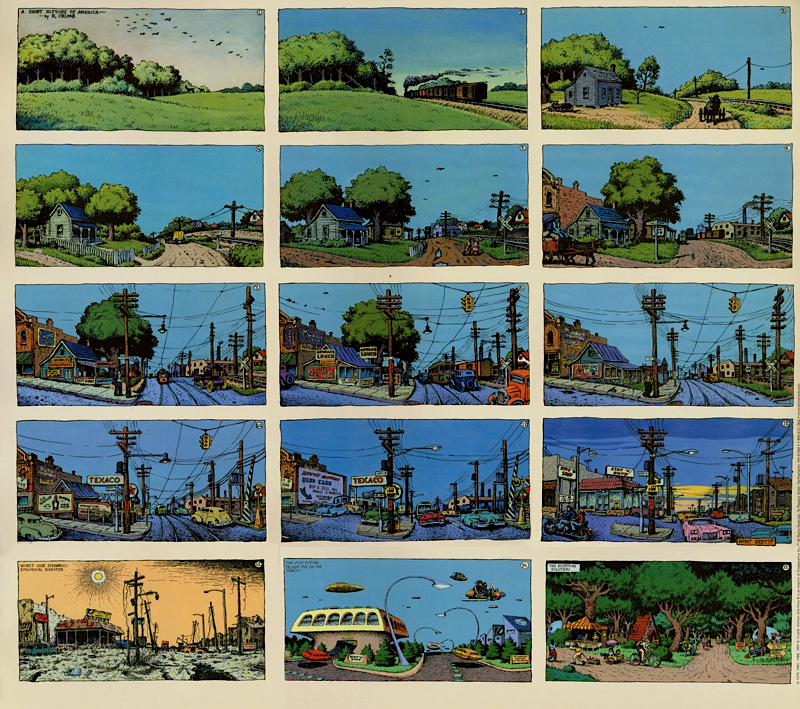

Da allora il fumetto di McGuire è stato paragonato a tante opere che hanno rivoluzionato la forma delle arti, ognuna ovviamente a suo modo. Ware lo paragona all’Ulisse di Joyce o anche a Fuoco pallido di Nabokov, citato per l’uso delle note a pié pagina, soluzione poi portata alle estreme conseguenze da David Foster Wallace. Matt Seneca in una bellissima recensione per The Comics Journal del nuovo Here utilizzava Il pasto nudo di William Burroughs e Viaggio nella luna di Méliès come opere altrettanto fondamentali per la loro ambizione formale. L’uso dello split screen nel cinema ha avuto sicuramente un ruolo importante nello sviluppo dell’idea iniziale di Here: esempi celebri sono Lo strangolatore di Boston, Il caso Thomas Crown, Carrie – Lo sguardo di Satana, probabilmente ben noti a McGuire. Per rimanere ai fumetti, invece, lo stesso Ware citava come possibili ispirazioni di McGuire The Malpractice Suite di Art Spiegelman e A Short History of America di Robert Crumb, il primo per la scomposizione quasi cubista della vignetta, il secondo per il modo in cui mostra l’evoluzione di uno stesso punto dello spazio nel corso del tempo. Di seguito le due opere citate (quella di Crumb è nella sua versione più recente, con l’aggiunta delle ultime tre vignette).

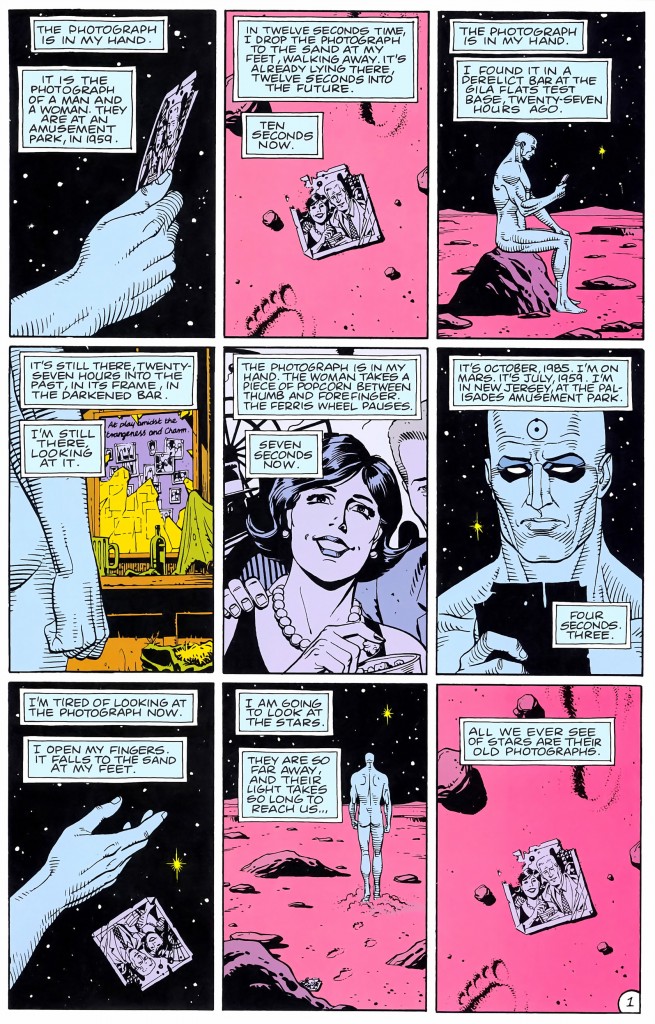

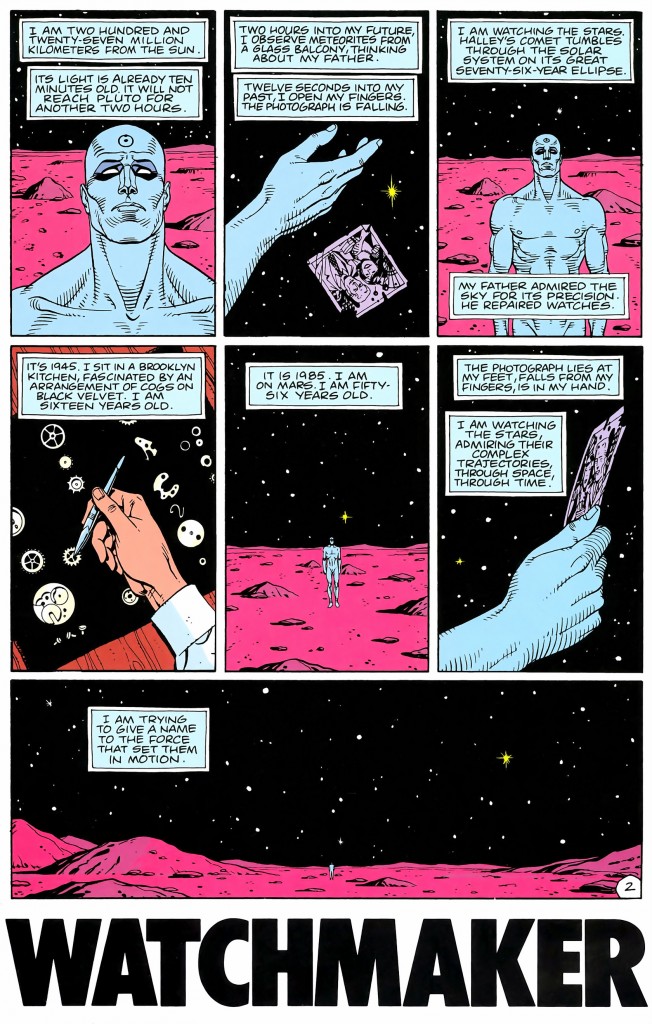

A me, innanzitutto appassionato dei comics nella loro declinazione anglo-americana, quando per la prima volta lessi Here venne banalmente in mente il quarto capitolo di Watchmen di Alan Moore e Dave Gibbons, non solo per il modo in cui la memoria del Dottor Manhattan salta da un anno all’altro, ma anche per come Moore dava veste divulgativa a quel concetto di simultaneità poi diffusissimo nella cultura popolare degli ultimi vent’anni, dal cinema al fumetto alle serie tv. Sicuramente le conoscerete già a memoria, ma queste sono le due pagine iniziali di Watchmen #4.

Subito dopo assistiamo alla scena del 7 agosto 1945 in cui il padre del Dottor Manhattan, dopo aver mostrato al protagonista la prima pagina del New York Times con la notizia della bomba atomica su Hiroshima, prende gli ingranaggi di un orologio e li butta dalla finestra. “Questo cambierà tutto. Ci saranno altre bombe. Sono loro il futuro. E mio figlio dovrà proseguire il mio lavoro obsoleto? (…) La scienza atomica… E’ di questo che il mondo ha bisogno! Basta con gli orologi! Il professor Einstein dice che il tempo varia da luogo a luogo. Hai idea? Se il tempo non è reale, a che servono gli orologiai, eh?”. Se il tempo è obsoleto nella realtà, figuriamoci nel fumetto, dove poco ci vuole a rompere il concetto tradizionale secondo cui i fatti raccontati in una vignetta siano precedenti a quelli che si vedranno nella successiva. E lo stesso vale nella letteratura, dove ci vuole ancor meno ad abbandonare l’idea di romanzo come successione di eventi per raccontare la storia di un luogo, come tra gli altri ha fatto lo stesso Alan Moore con la sua bellissima e sghemba storia di Northampton contenuta in La voce del fuoco.

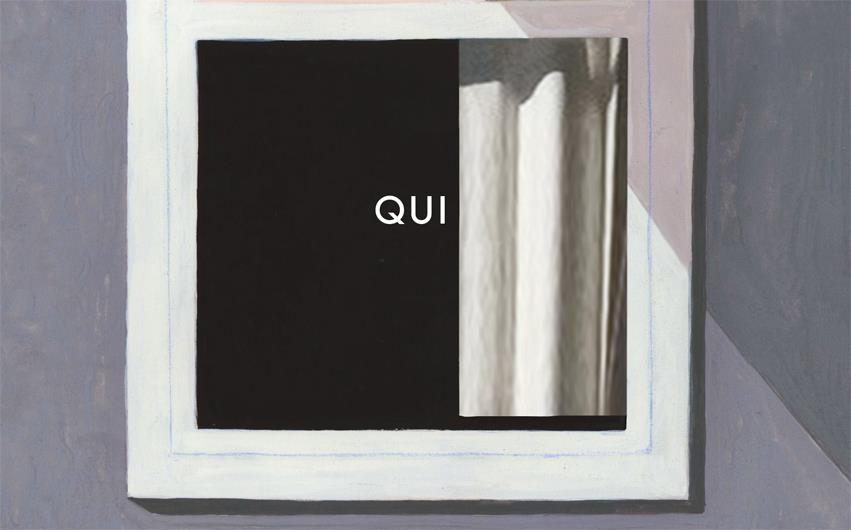

Prima ho usato in modo un po’ criptico l’aggettivo “nuovo” riferendomi a Here. Ma d’altronde ormai ben saprete che McGuire ha rivisitato il concept originale in una nuova edizione, che dopo una lunga gestazione è uscita lo scorso anno sotto forma di un libro a colori di oltre 300 pagine pubblicato da Pantheon Books e arrivato anche in Italia da qualche settimana grazie a Rizzoli Lizard con il prevedibile titolo di Qui. Se qualche fedele lettore di queste pagine si fosse chiesto perché non avevo incluso il volume nella lista dei migliori fumetti del 2014, è perché all’epoca ancora non avevo letto il nuovo Here, dato che una copia spedita in anteprima grazie a qualche aggancio oltreoceano si era perduta nei meandri del sistema postale mondiale e si era infine palesata dopo mesi di attesa, quando il libro era già da un bel po’ di tempo nelle librerie.

Here parla dell’essere umano, sia nel senso di “umanità” che in quello di “uomo” e l’opposizione o meglio la giustapposizione di questi due concetti è ancora più evidente nella versione graphic novel. Se le sei pagine originali sfoggiavano una narrazione convulsa, veloce, dinamica, rappresentando come nessun fumetto aveva mai fatto prima le dinamiche del pensiero, le 300 pagine della versione 2014 sono lente, pacate, a tratti malinconiche nel modo di accostare l’inesorabilità del Tempo e della Storia alle piccole vicende quotidiane delle persone comuni, a ricordarci, come diceva McGuire, che noi sperimentiamo soltanto una parte delle possibilità di questo mondo, che quello che accade nel nostro piccolo è niente rispetto alle ere geologiche, all’estinzione delle specie, a un futuro che – almeno secondo quanto dicono queste pagine – riporterà la Terra indietro, verso le sue origini. Il tutto è ovviamente riportato secondo la sensibilità di un uomo occidentale che ha vissuto e vive tra il XX e il XXI secolo, ma non potrebbe essere altrimenti, dato che pur trattando di temi universali si tratta sempre di un’opera personale, in cui l’autore ci ha inevitabilmente messo del suo.

Il solito Chris Ware è tornato su Here per parlare delle sua nuova incarnazione, dicendo che “con quelle prime sei pagine nel 1989, McGuire ha introdotto un modo nuovo di fare una striscia a fumetti, ma con questo volume, nel 2014, ha introdotto un nuovo modo di fare un libro”. Ma cosa c’è, dunque, dentro queste 300 pagine? Innanzitutto c’è una visione più ampia di quel famoso spicchio di realtà. Se nella striscia infatti l’unità narrativa era rappresentata dalla vignetta, qui è costituita dalla doppia pagina, cosa che permette all’autore di allargare la prospettiva mostrandoci non solo quell’angolo in alto a sinistra (secondo la nostra percezione) ma anche altre porzioni delle stanza. Per esempio guardando la prima versione non avevamo mai visto il camino, lo specchio, quel tavolino, quell’abat-jour. Inoltre non avevamo mai visto i colori, realizzati grazie all’aiuto di Min Choi, Maëlle Doliveux, Keren Katz, definiti come “Team Here” perché hanno aiutato l’autore negli aspetti più tecnici del processo creativo, portando alla realizzazione di un affascinante ibrido tra matite, computer grafica, colori digitali e splendidi acquerelli. L’uso del colore cambia l’estetica della storia e anche se la tavolozza cromatica è molto ampia, a prevalere sono i temi tenui del giallo/marrone/ocra, che ricreano un mood simile a quello dei quadri di Edward Hopper. E spesso, vedendo quel salotto e le sue evoluzioni nel corso del Novecento, sembra di stare in un libro di qualche maestro del racconto americano come Richard Yates o Raymond Carver.

D’altronde Here è a suo modo un libro di racconti, in cui brevi storie si accumulano, si sviluppano e a volte si intrecciano. Ma è anche un susseguirsi di associazioni di idee, di temi che vengono trattati per qualche pagina per poi lasciare spazio ad altri, mentre le finestre si aprono e si incastrano tra loro e gli anni vanno avanti, indietro, avanti e ancora indietro. Dentro c’è la rappresentazione di panorami astratti dai colori vivacissimi nel 3.000.500.000 a.C., di animali preistorici nel 10.000 a.C., di splendidi e incontaminati scenari lacustri nell’8000 a.C. come nel 1203 e nel 1307, di due indigeni che fanno l’amore nel 1609, di Benjamin Franklin che discute di politica con il figlio nel 1775, di case che vengono costruite nel 1907, della vita secondo le forme ben conosciute del XX secolo (poi raccontata da una guida turistica nel 2213), del mondo dopo un non meglio identificato evento catastrofico nel 2313, di animali a noi sconosciuti che vagano nell’oscurità del 10175, di forme di vita nuove e colorate che appaiono nel 22175. Ci sono foto di famiglia fatte in anni diversi sullo stesso divano, madri che tengono in braccio i loro figli nel 1924 come nel 1945, nel 1949 e nel 1988, feste di carnevale, party, bambine che ballano. C’è una bellissima pagina ambientata nel 1949 in cui lo specchio sopra al camino cade e mentre una vignetta più grande ci mostra l’acqua che entra in casa dalla finestra in una notte del 2111, ci sono tantissime finestrelle che ci mostrano piatti e bicchieri che si rompono e insulti che volano letteralmente in aria, neanche fossimo in un trattato sociologico sull’evoluzione del linguaggio. E poi c’è la storia della stanza, con la carta da parati che viene sostituita nel 1949 per poi essere coperta dalla pittura nel 1960, lo specchio sopra al camino che lascia spazio a un quadro, poi sostituito da un altro specchio, quindi da un televisore da parete che diventerà obsoleto nel 2050 davanti alle nuove tecnologie da salotto. C’è anche il dramma in Here, dato che nelle prime pagine siamo nel 1989 e un uomo dopo aver ascoltato una barzelletta inizia a ridere, quindi a tossire e infine cade a terra, anche se per vedere la reazione dei familiari dovremo aspettare di arrivare quasi a metà volume, in una pagina ambientata sempre nel 1989 ma in cui c’è anche una donna che nel 1960 dice “Did you lose something?”, collegandosi alla morte dell’uomo e contemporaneamente dando il via a una sequenza di diverse pagine con personaggi che perdono oggetti personali oppure la testa, la vista, l’udito.

Capita raramente di trovare delle opere formalmente innovative che siano in grado al tempo stesso di parlare al cuore del lettore. Here è una di queste e l’effetto ottenuto da McGuire è ancora più straordinario se pensiamo che riesce a pungolare, a emozionare, a stupire senza fare uso di trame né di protagonisti, ma semplicemente raccontando la Storia e le storie, il grande e il piccolo, il grave e l’irrilevante, il serio e il faceto. La metafora più efficace di tutto ciò è nelle pagine iniziali, quando nel 1957, l’anno da cui partiva la versione originale di Here, una donna entra nella stanza e si chiede “Hmm… Now why did I come in here again?”. La domanda – autobiografica e metanarrativa – rimane in sospeso mentre leggiamo e la risposta arriva soltanto alla fine: la donna è entrata per prendere un libro. E – come cantavano i Pavement – tutto finisce qui.

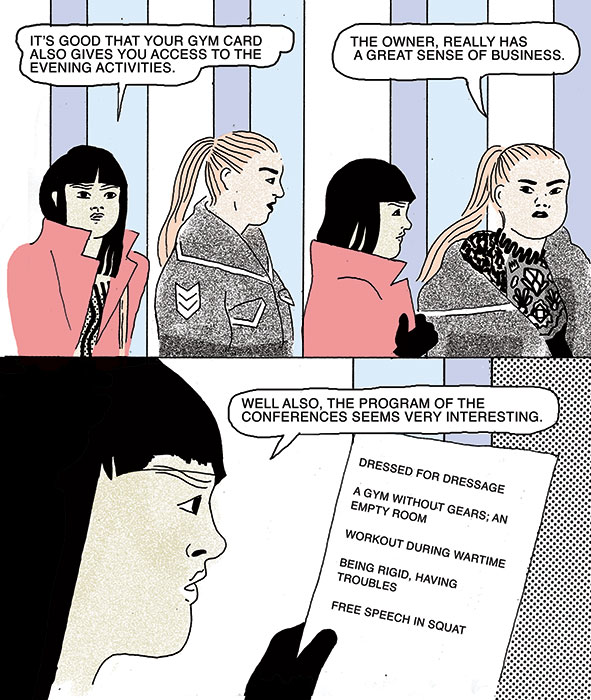

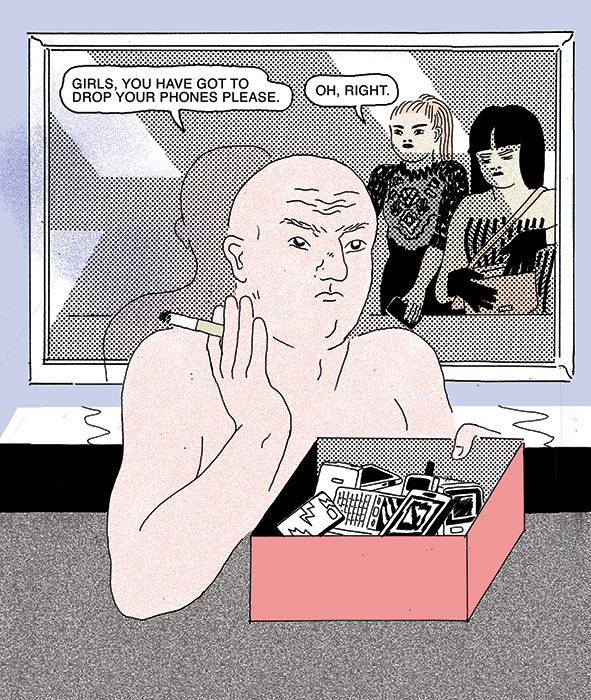

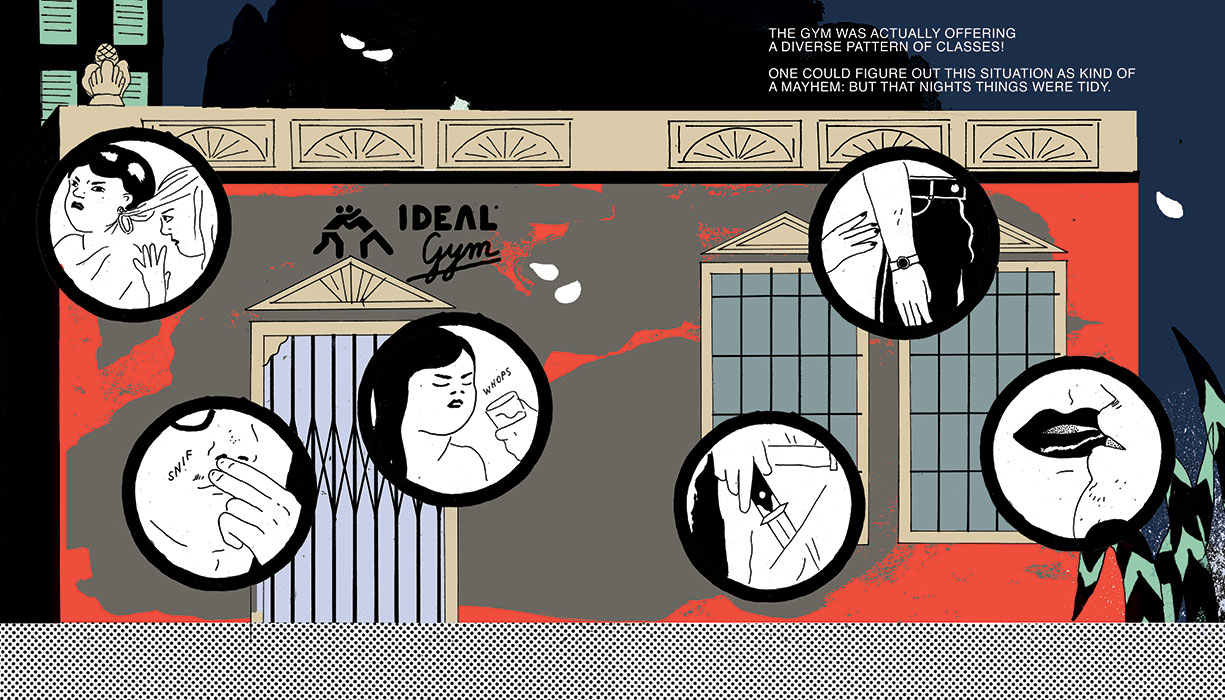

Le prime pagine di “Frontier” #8 di Anna Deflorian

Ha esordito lo scorso fine settimana al Toronto Comic Arts Festival l’ottavo numero di Frontier, l’antologia monografica pubblicata dalla Youth In Decline di San Francisco, realizzato dalla nostra Anna Deflorian. Ryan Sands, patron della casa editrice, aveva conosciuto la Deflorian grazie al contributo dell’illustratrice trentina al nono numero dell’antologia baltica š!. Le tematiche di quel breve racconto e le inquietudini, le pulsioni, le emozioni nascoste delle protagoniste di Roghi, volume del 2013 targato Canicola Edizioni, tornano in queste pagine. Due donne, un uomo incontrato in palestra, un cellulare smarrito con qualche foto osé sono gli elementi di una narrazione scandita attraverso tavole finemente decorate e dalle geometrie inusuali. Di seguito le prime pagine di Faith in Strangers.

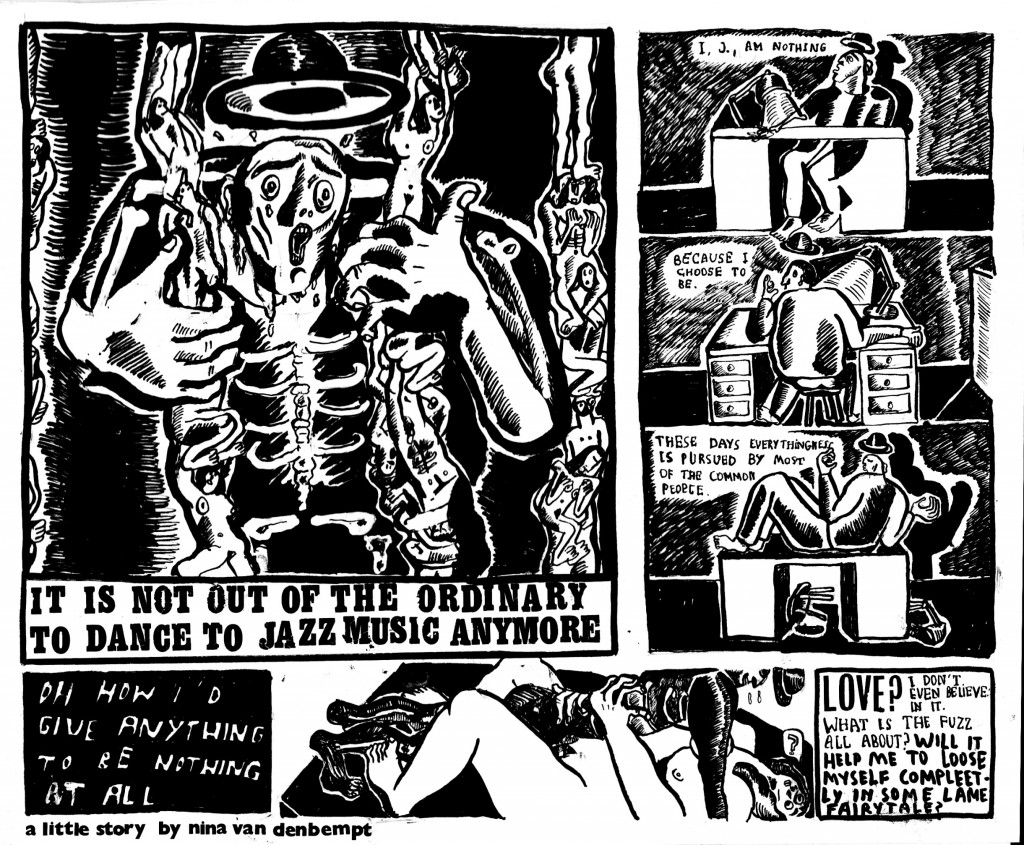

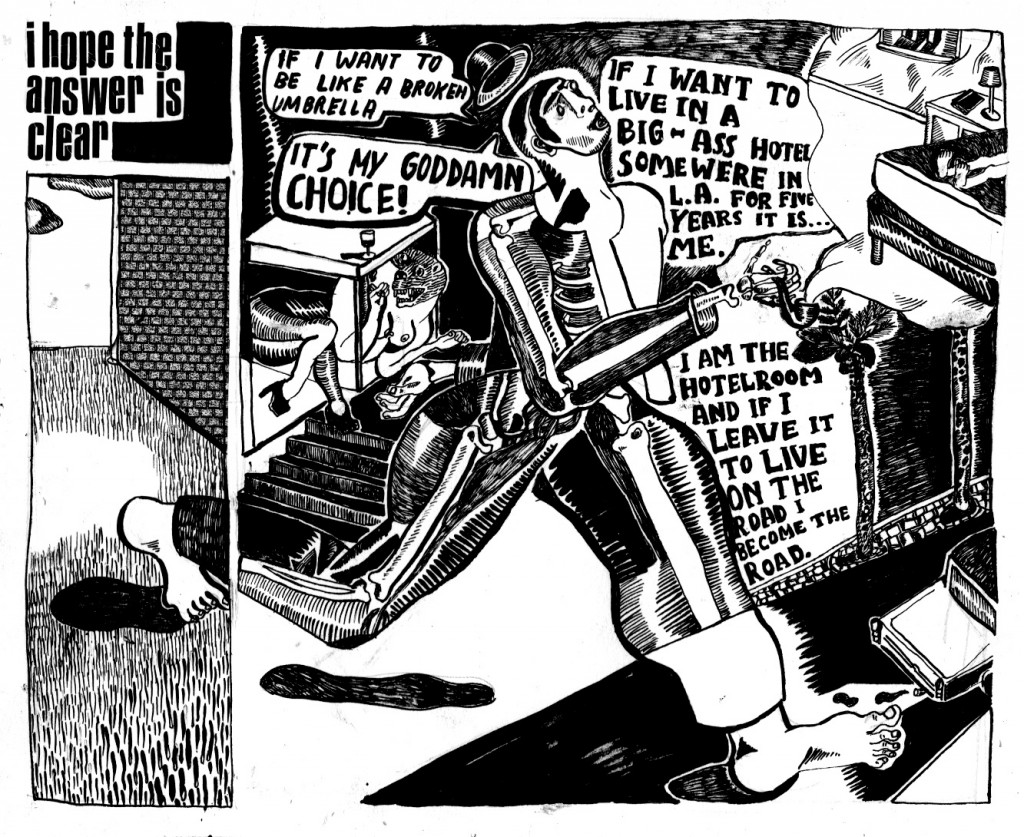

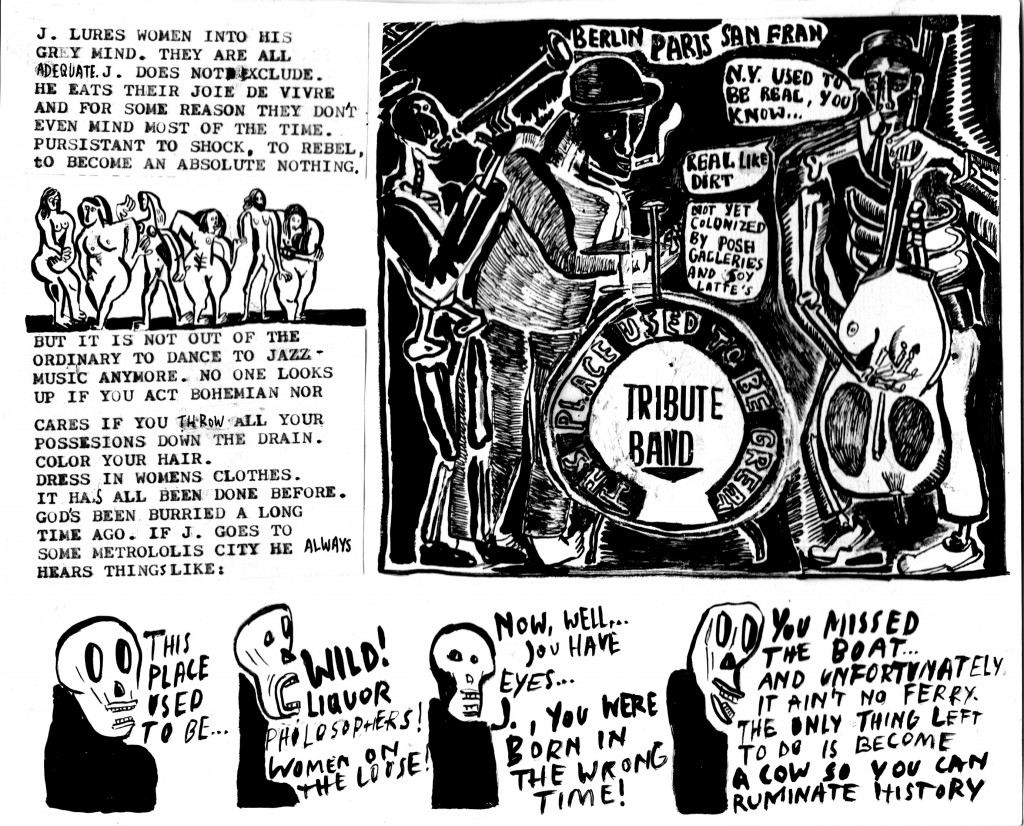

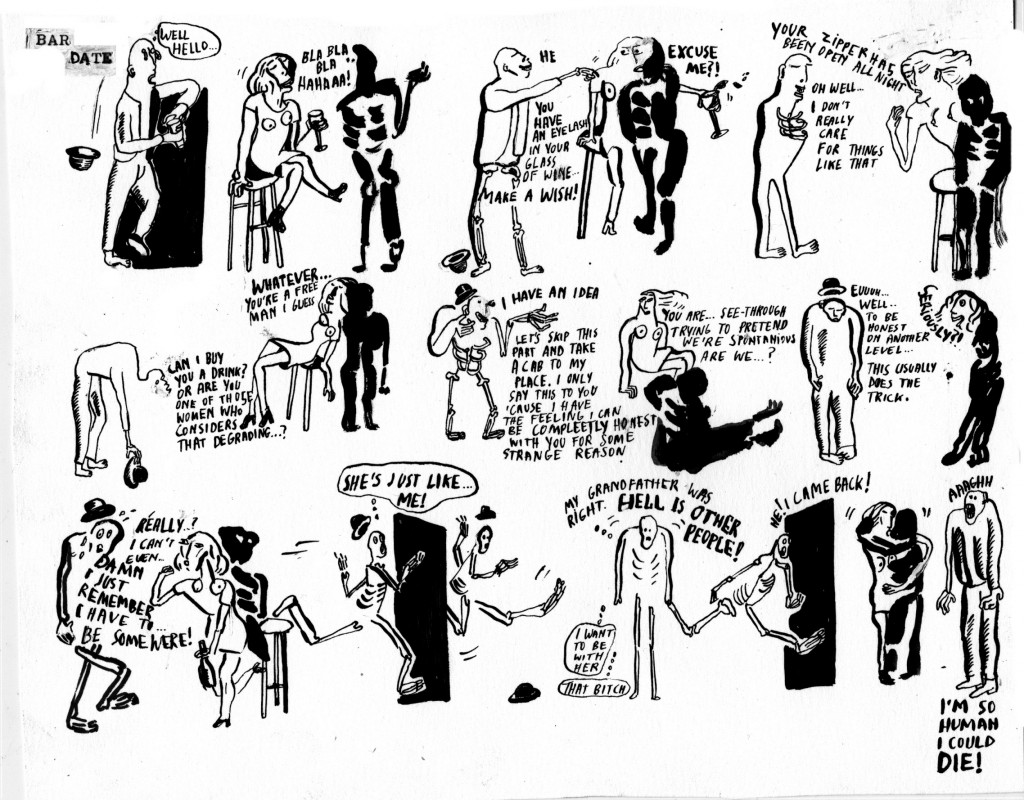

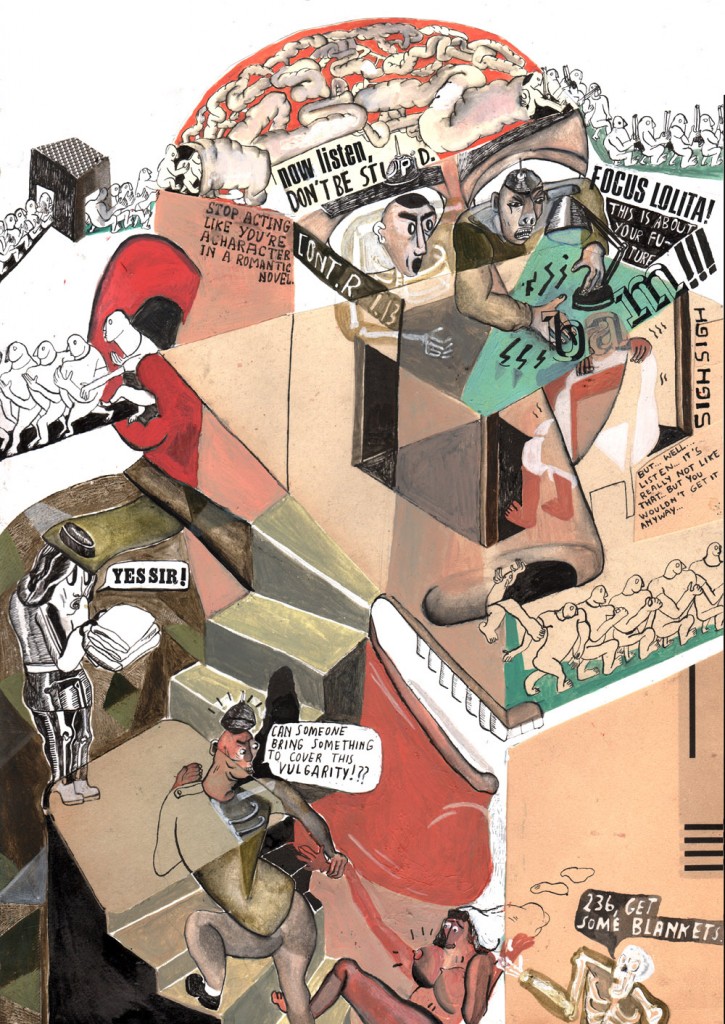

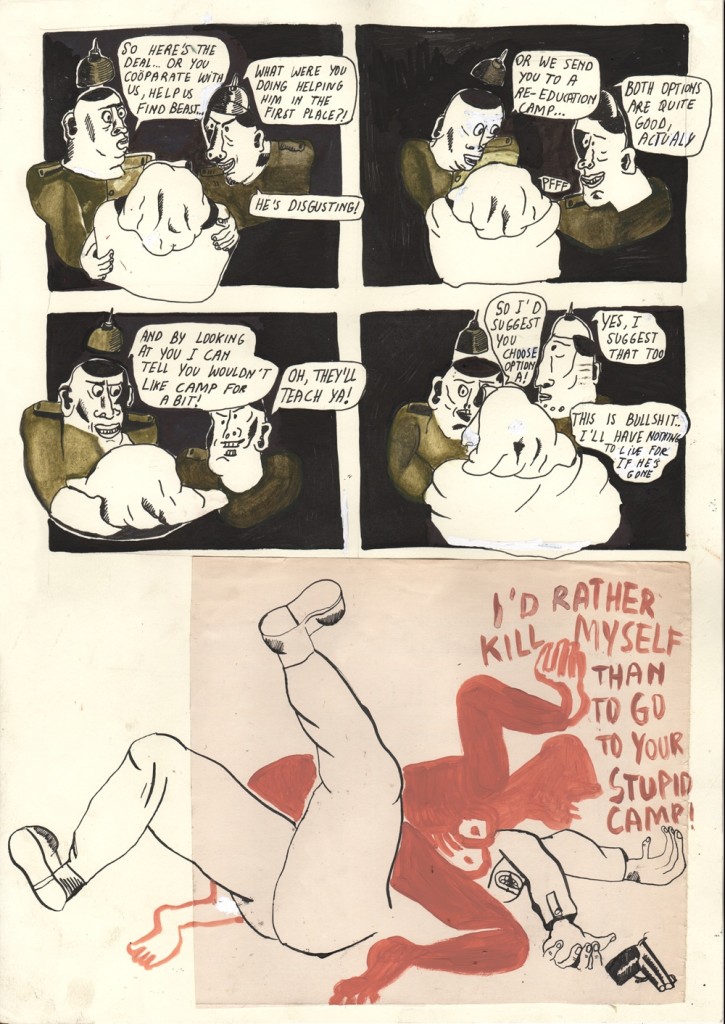

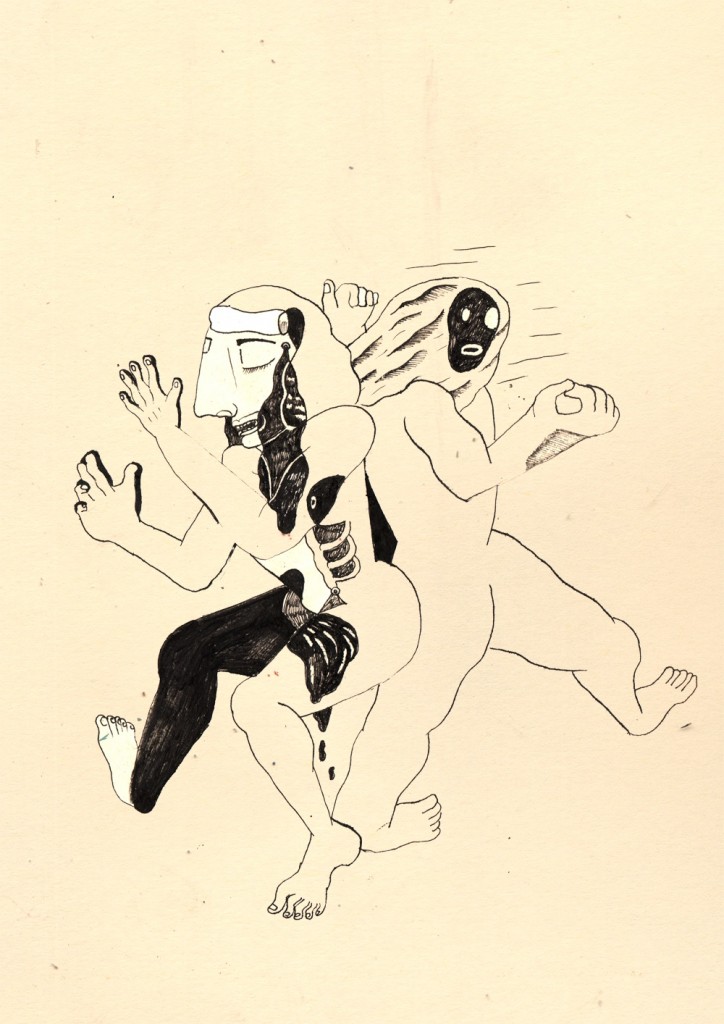

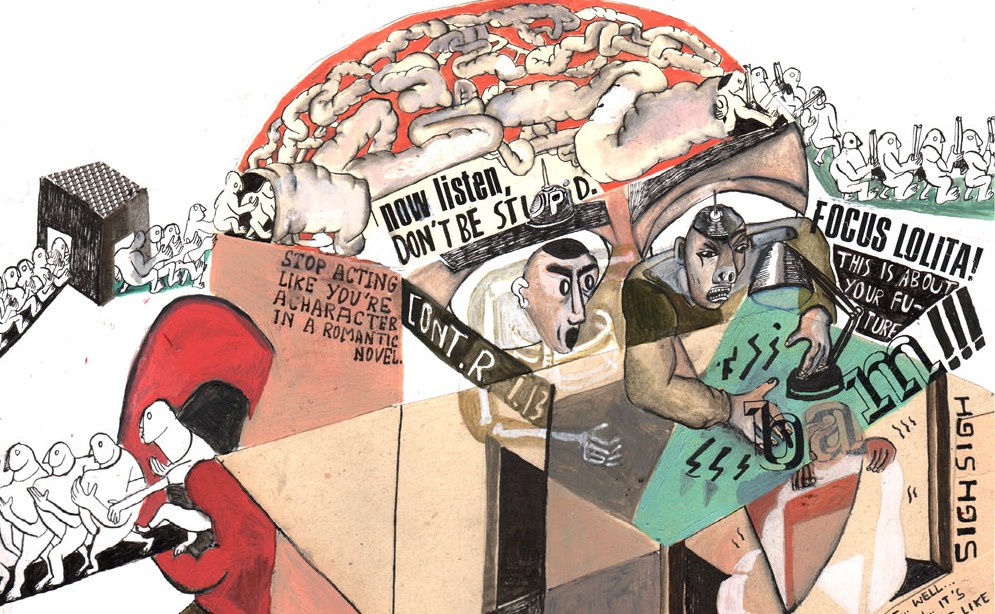

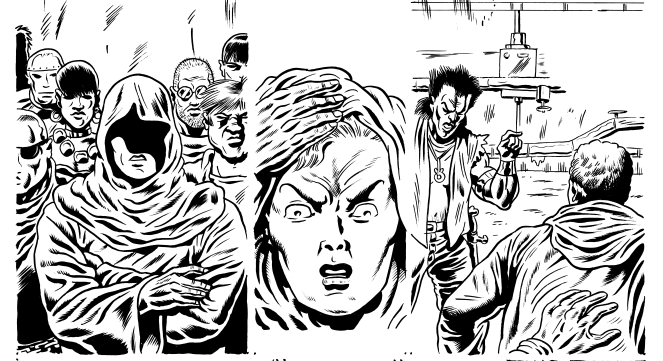

Due fumetti di Nina Van Denbempt

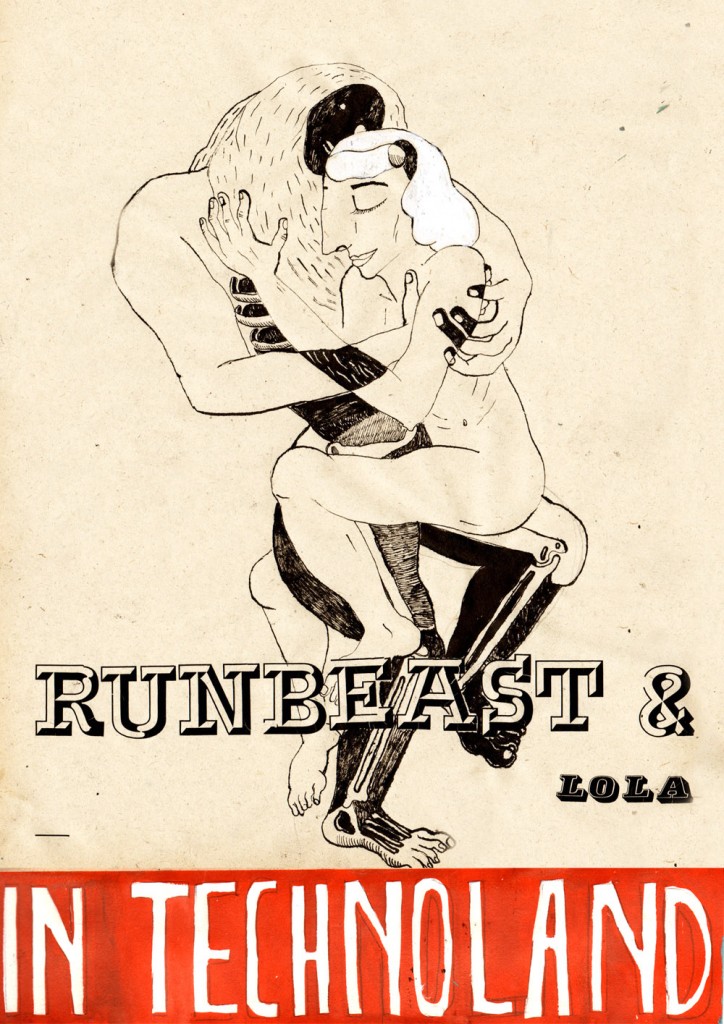

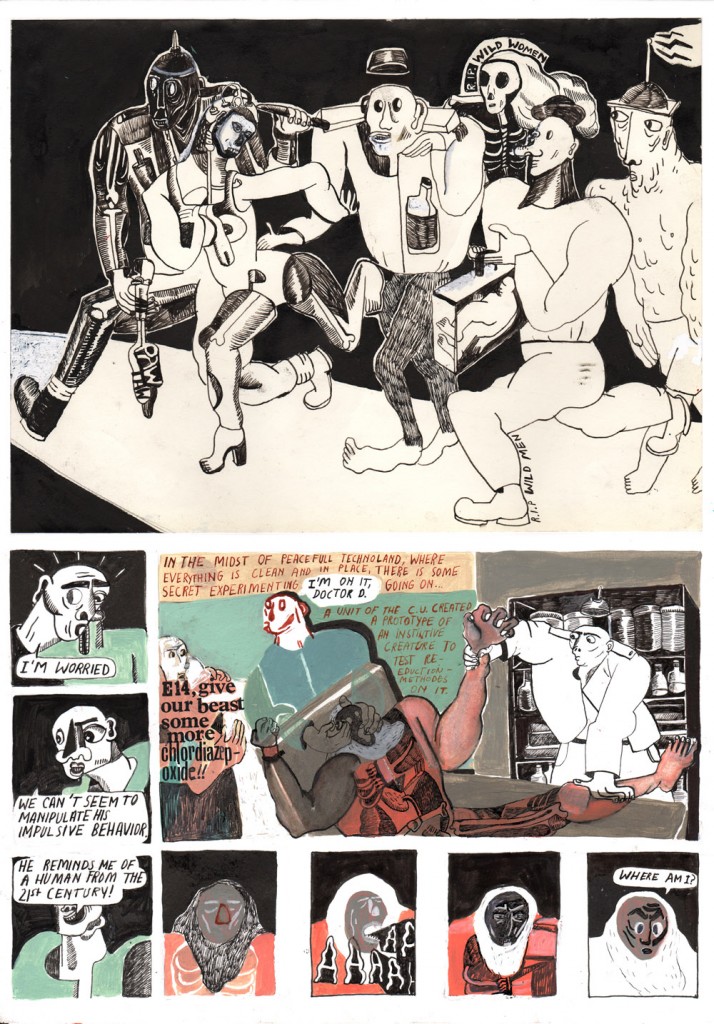

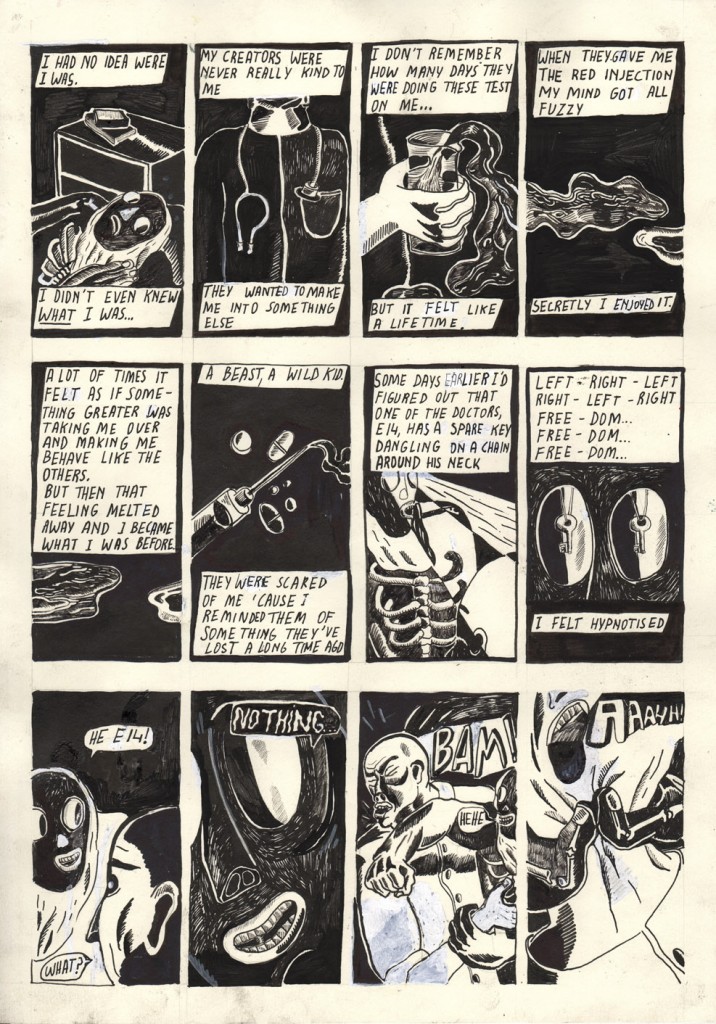

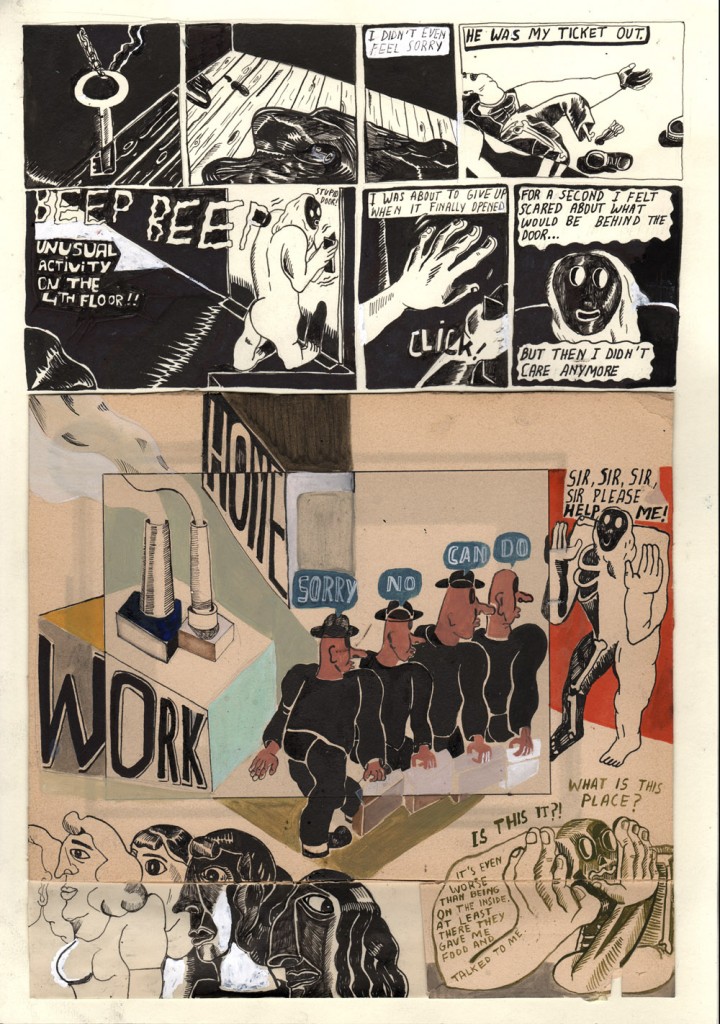

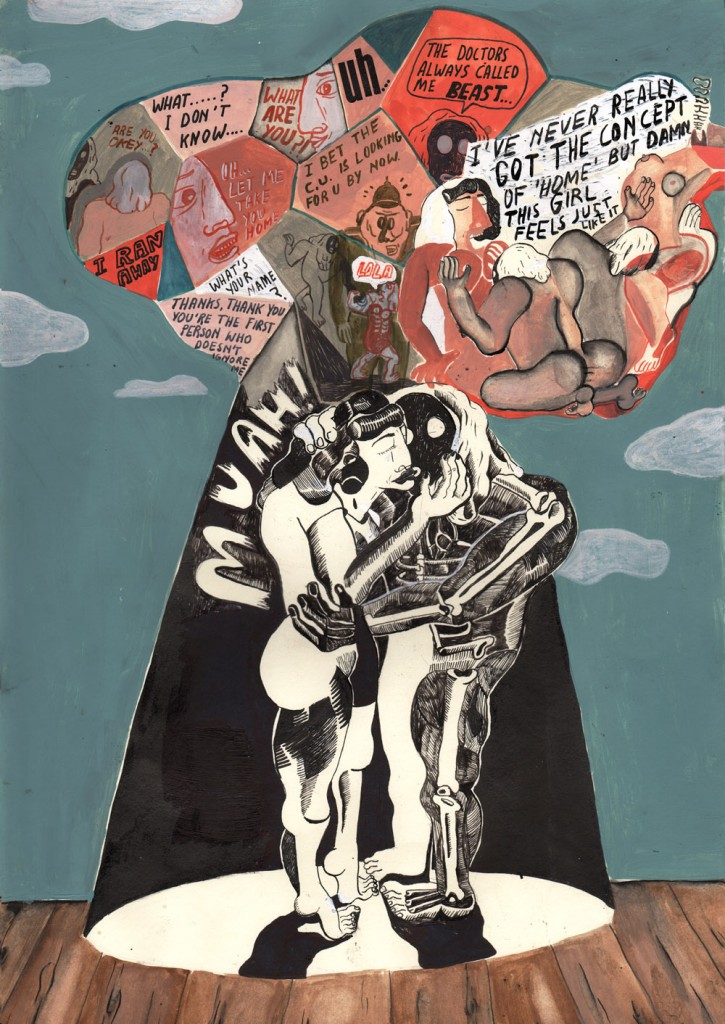

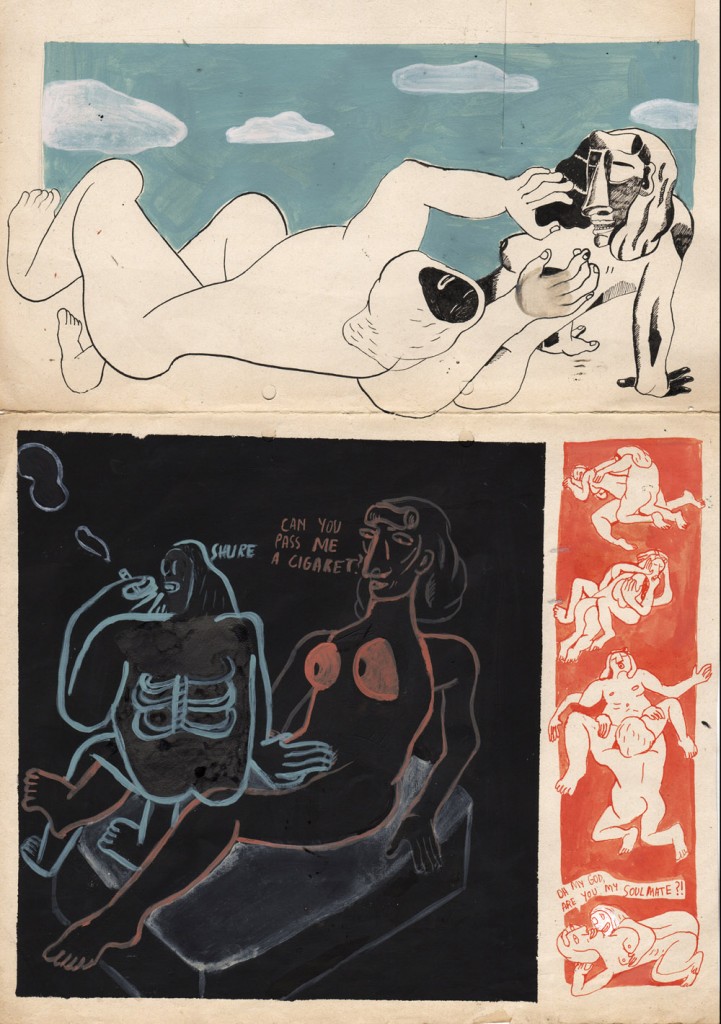

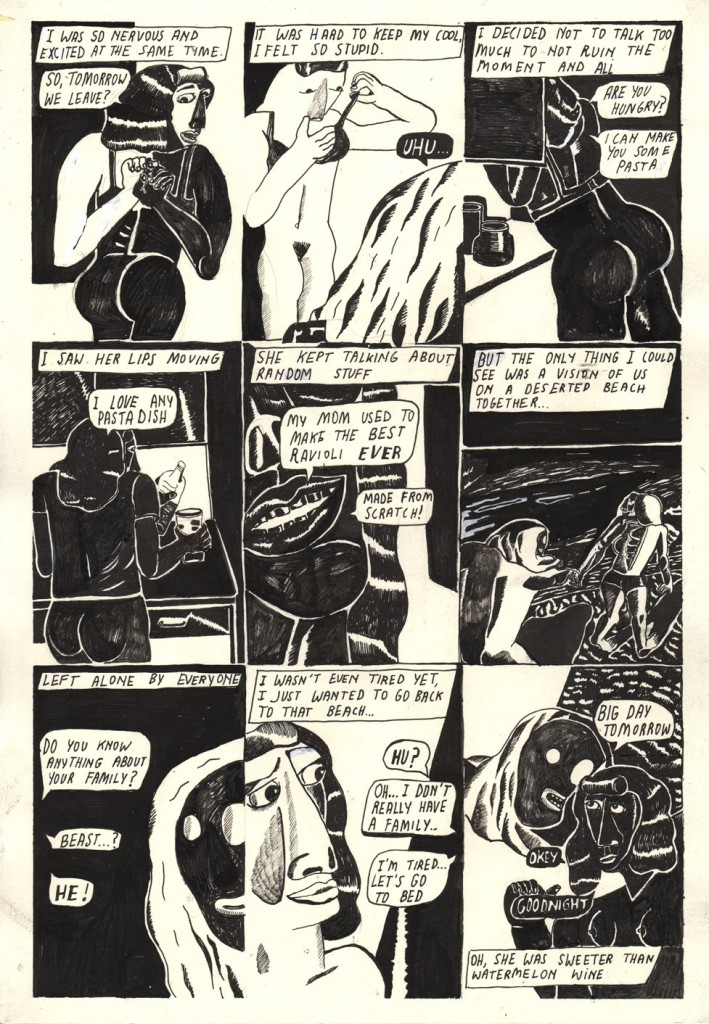

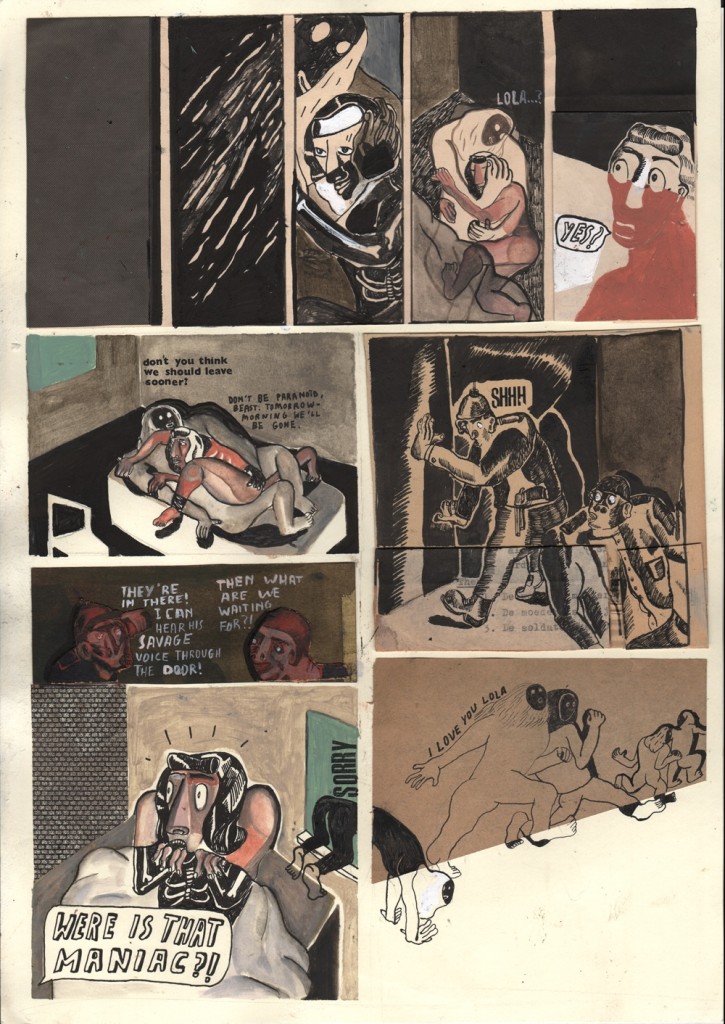

Nina Van Denbempt è un’autrice belga classe ’89, cresciuta artisticamente a Gent, splendida cittadina delle Fiandre che di recente ha sfornato i talenti di Brecht Evens e Brecht Vandenbroucke. Insieme ad alcune compagne della scuola d’arte Sint-Lucas, dove si è diplomata in illustrazione, Nina ha formato il collettivo Tieten Met Haar ed è nel quarto numero del’omonima antologia che ho visto per la prima volta il suo lavoro, in cui i corpi deformati, il lettering irregolare, la giustapposizione di tecniche diverse danno vita a pagine coraggiose e mai banali, come potete vedere dai due fumetti in basso. Il primo è It is not out of the ordinary to dance to jazz music anymore, una storia di quattro pagine vista sia sull’antologia Tieten Met Haar che sulla zine autoprodotta Captain Foggy Brain, caratterizzata da un lirismo stemperato dalla giusta dose di ironia. Uno dei leitmotiv dell’opera della cartoonist belga sembra la banalità del quotidiano e dei suoi rituali e si trova anche nella seconda proposta, Runbeast & Lola in Technoland, dalla trama più strutturata e ambientata in un futuro regime repressivo, con un uso originale del colore. Nina è attualmente a lavoro sulla sua prima opera lunga, Barbarians, una storia d’amore sullo sfondo di un’Europa post-apocalittica.

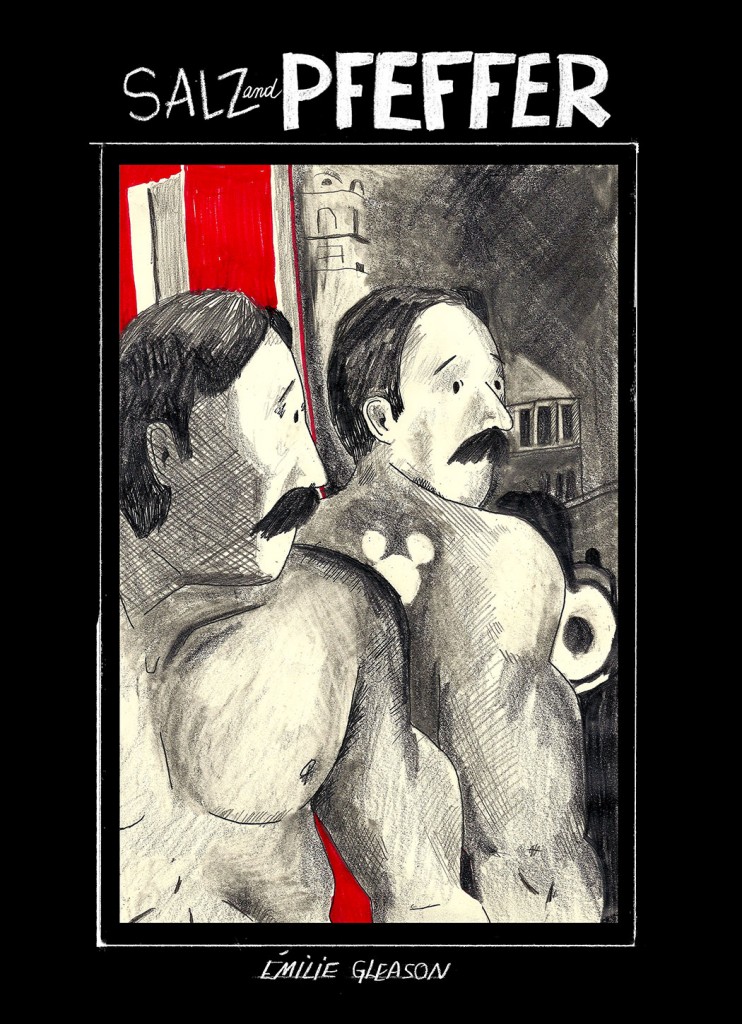

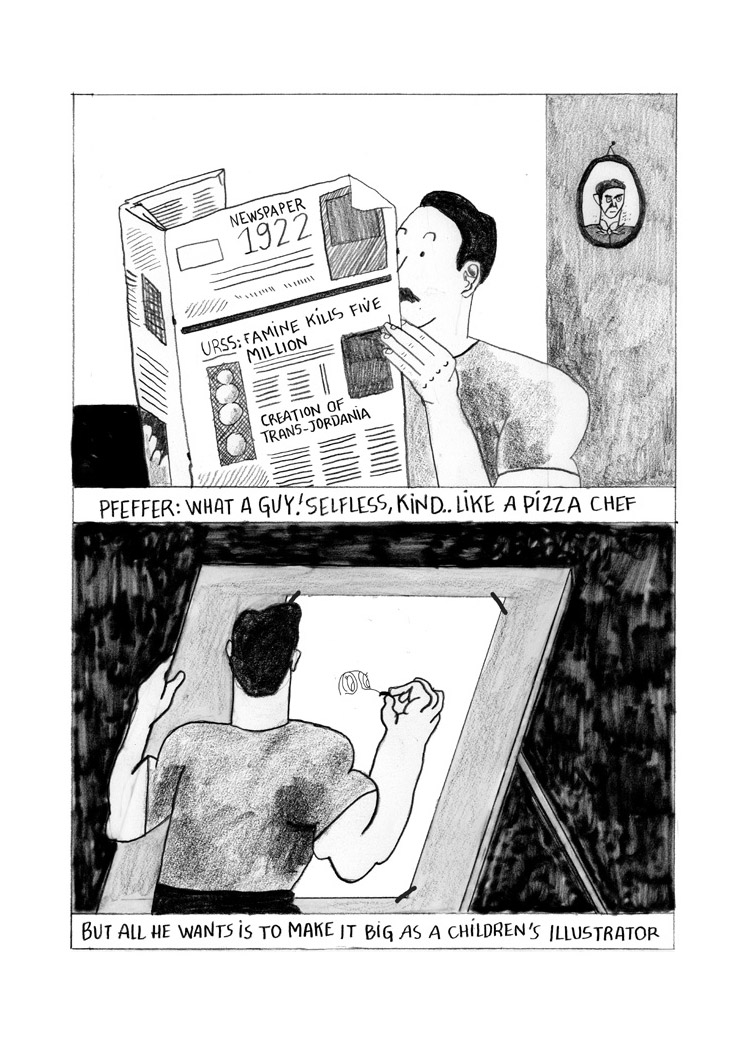

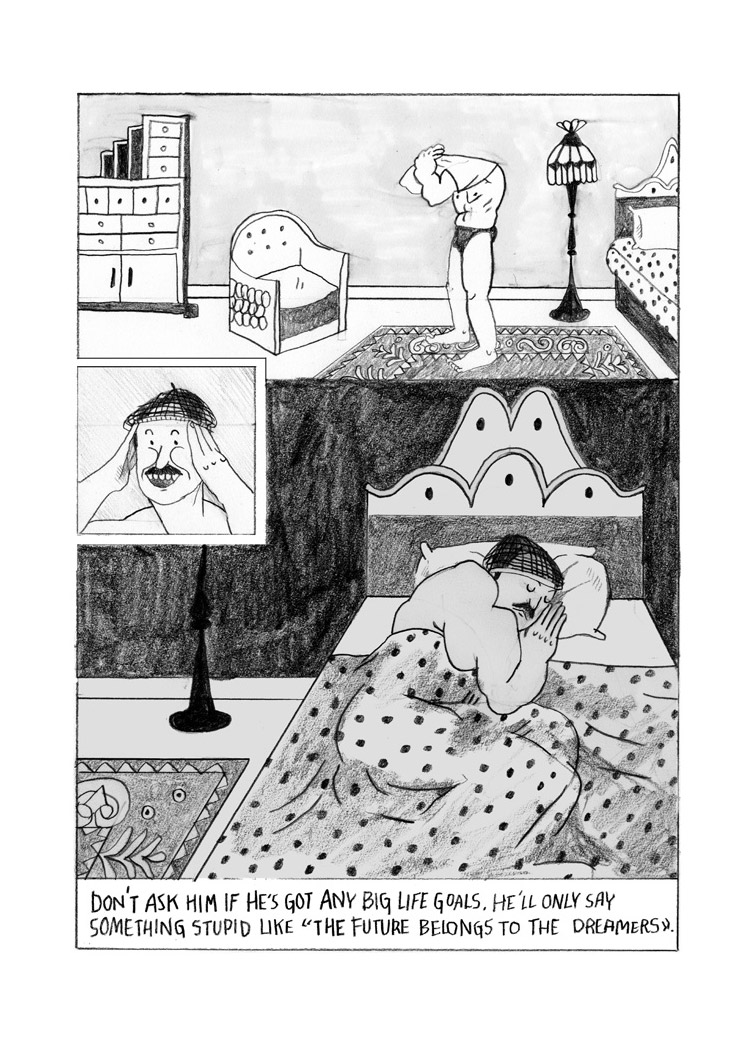

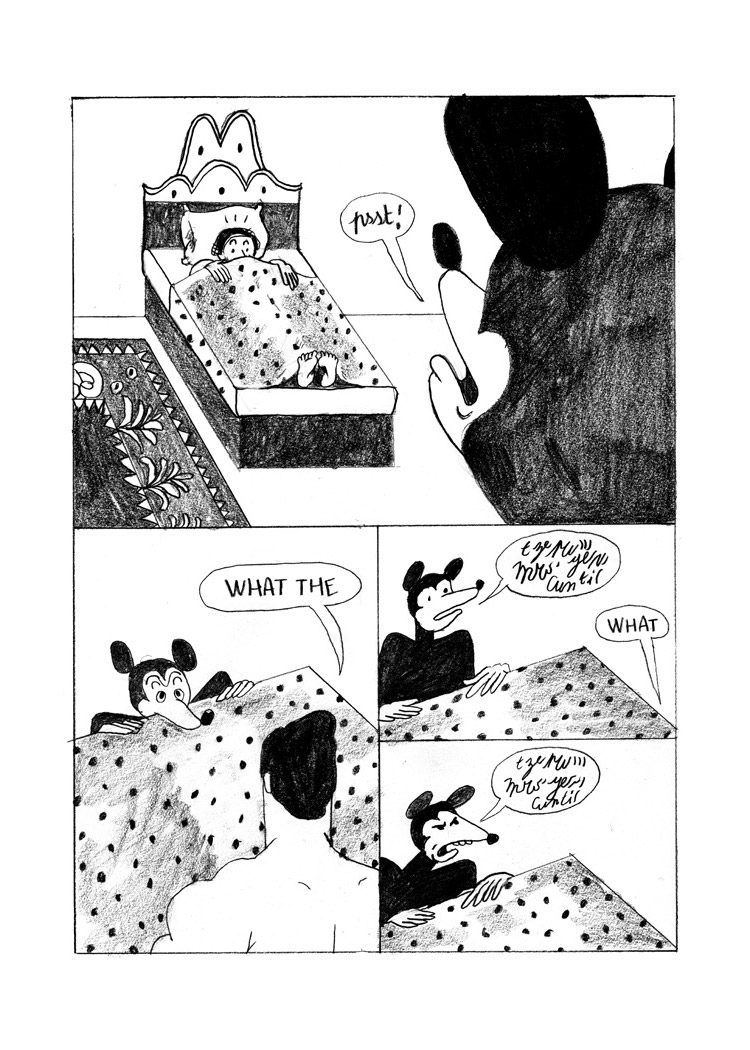

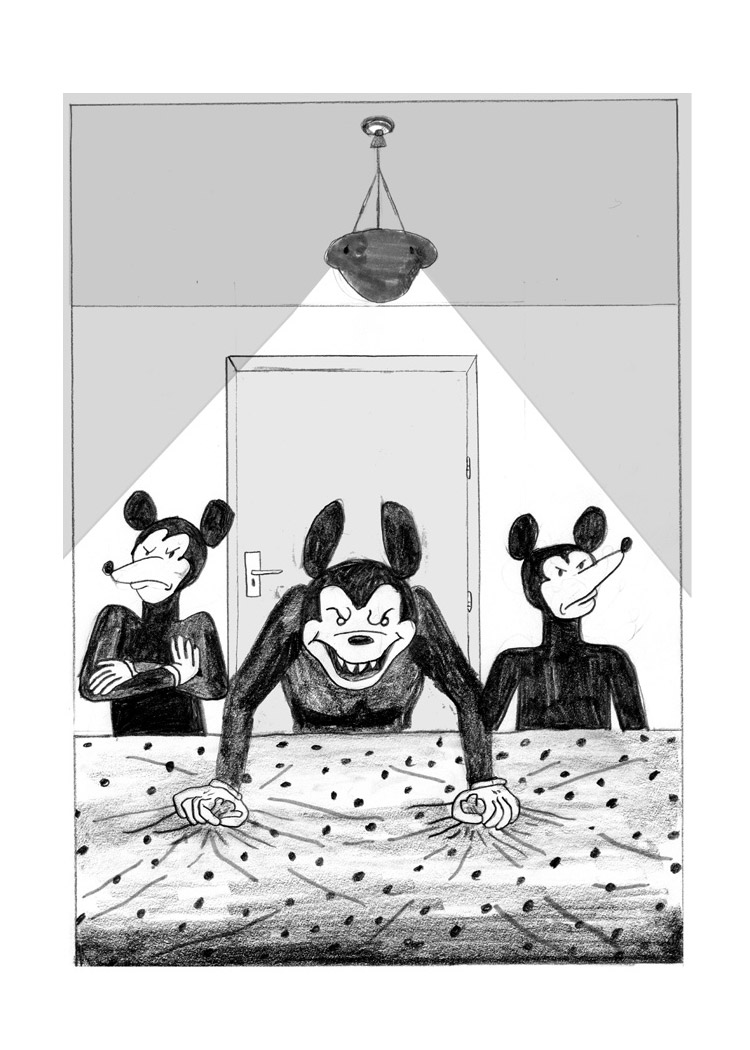

“Salz and Pfeffer” di Émilie Gleason, un’anteprima

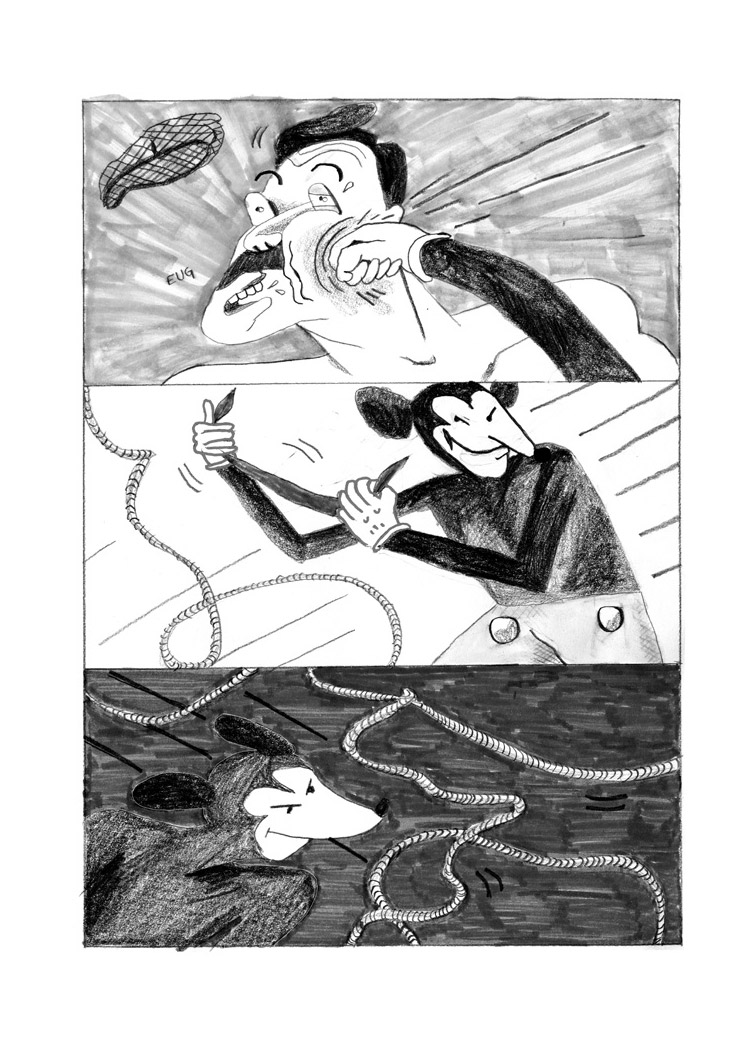

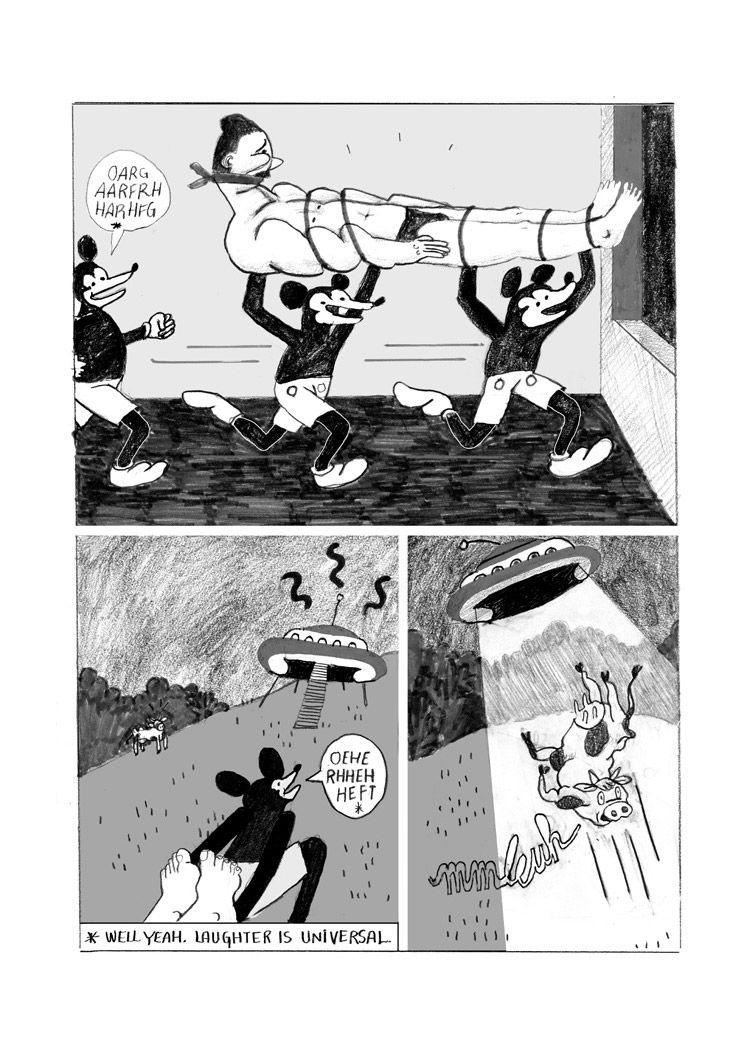

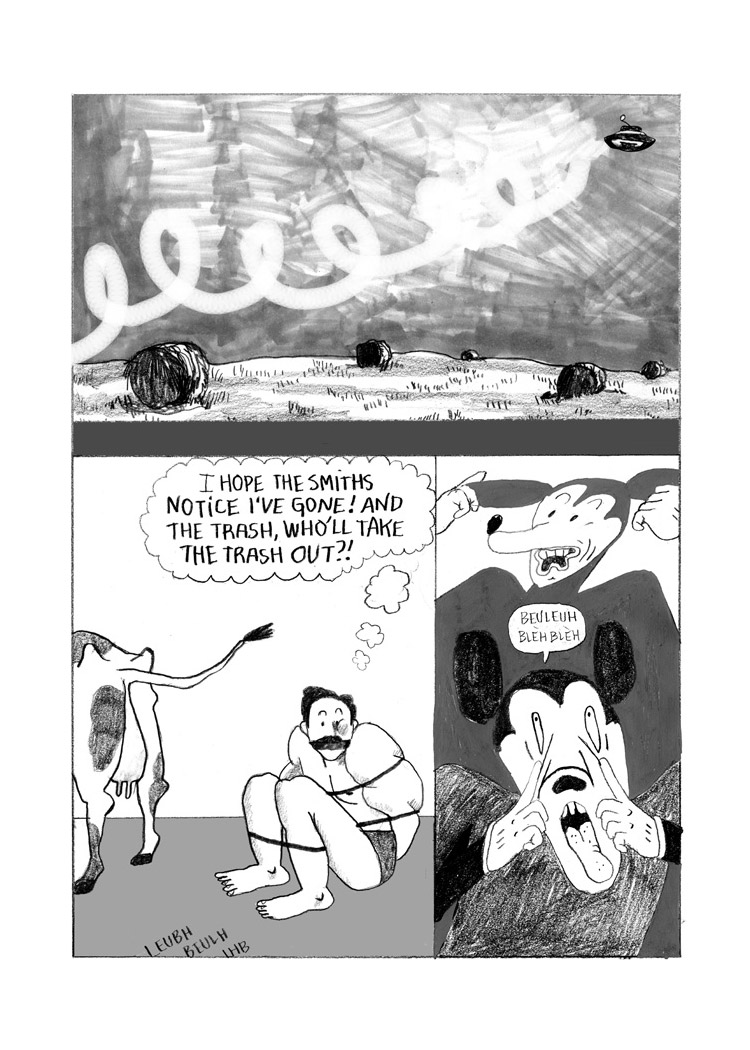

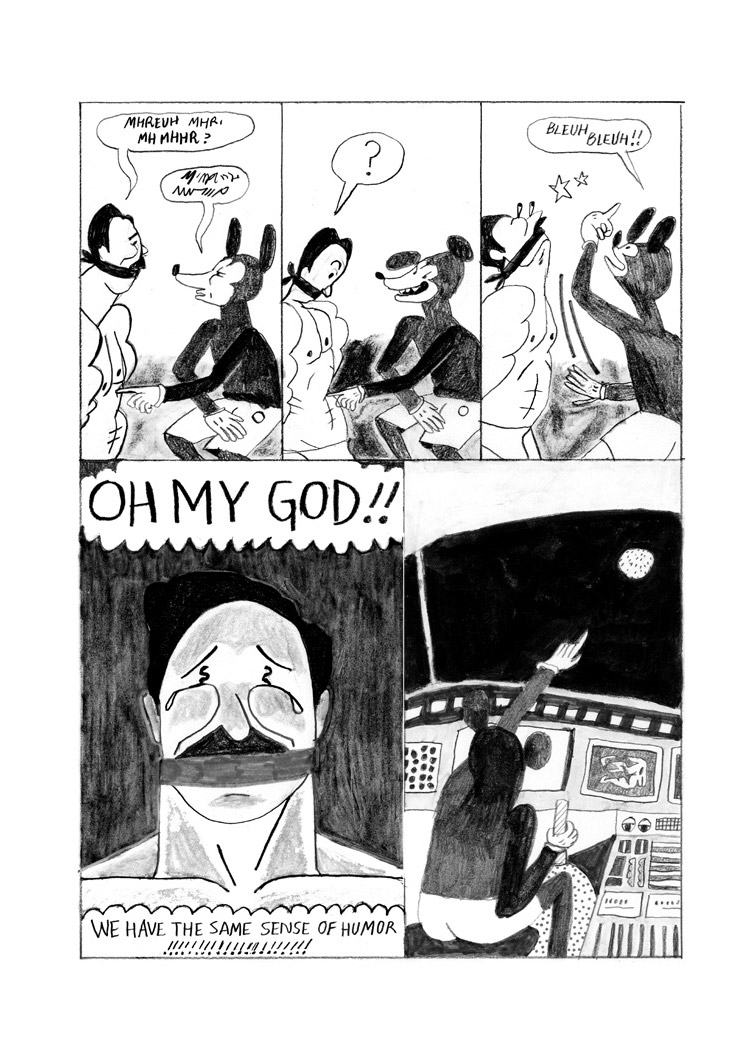

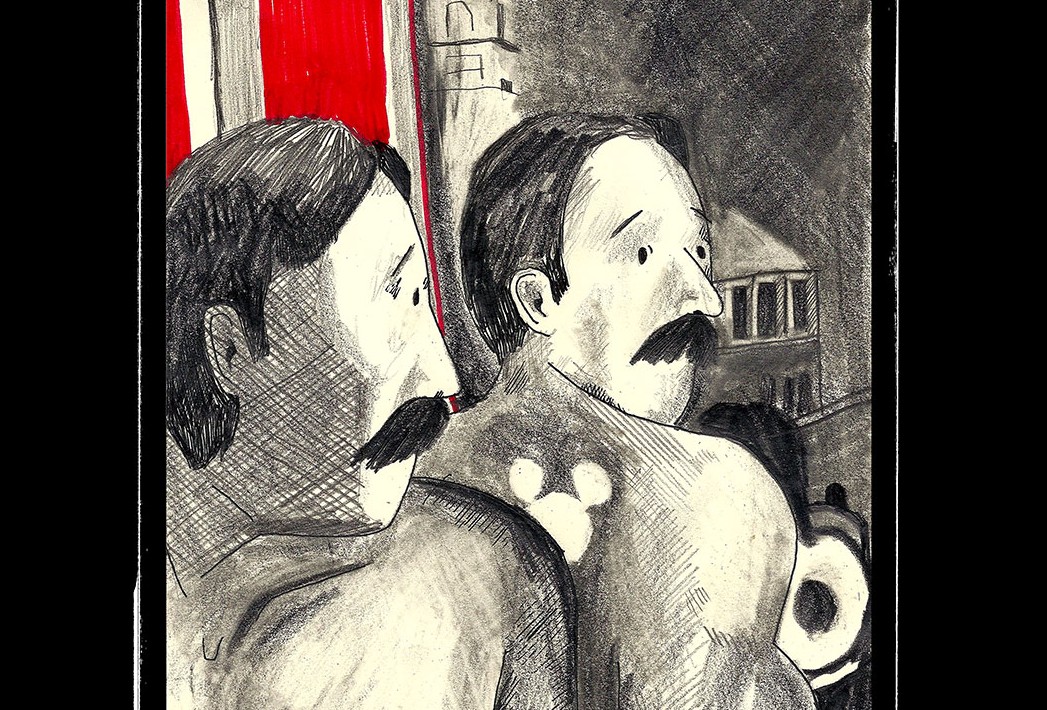

Nata in Messico, Émilie Gleason ha vissuto tra Belgio e Francia e sbarca ora negli Stati Uniti con il suo primo libro per il mercato nord-americano, pubblicato dalla 2D Cloud di Minneapolis e presentato lo scorso fine settimana al Toronto Comic Arts Festival alla presenza dell’autrice. Un uomo baffuto, ordinato, rispettabile, Pfeffer sogna di fare il disegnatore per bambini ma una notte viene rapito dagli alieni, in realtà tre versioni oblunghe e cattive di Mickey Mouse. Salz and Pfeffer è un libro divertente, disegnato con uno stile a matita d’altri tempi e dotato di un forte senso della dinamicità. Il lavoro della Gleason rilegge in chiave cartoon quello di autori come C.F. e Gabriel Corbera e questo viaggio di 76 pagine violento, ironico, surreale merita la vostra attenzione, come d’altronde i lavori autoprodotti dall’autrice, disponibili nel suo negozio online. Di seguito le prime pagine del volume.

Il meglio del Web – 7/5/2015

Secondo appuntamento con questa rassegna di notizie, link e segnalazioni varie. Iniziamo dalle novità in casa Youth In Decline. La casa editrice di San Francisco ha da poco pubblicato il settimo numero della serie monografica Frontier, a firma Jillian Tamaki, autrice insieme alla cugina Mariko della pluripremiata graphic novel This One Summer, tradotta da Bao Publishing con il titolo E la chiamano estate. Ancora non ho potuto vederlo di persona, ma la recensione di Alex Hoffman su The Sequential State non fa che incuriosirmi ulteriormente. SexCoven, questo il titolo della storia, è ambientata all’inizio dell’epoca del file sharing e parla di un culto legato a un misterioso file mp3. Intanto sono disponibili le prime immagini dell’ottavo albo di Frontier, firmato dall’italiana Anna Deflorian. E sul blog della casa editrice di Ryan Sands vengono riproposte le interviste agli autori dei precedenti numeri della serie.

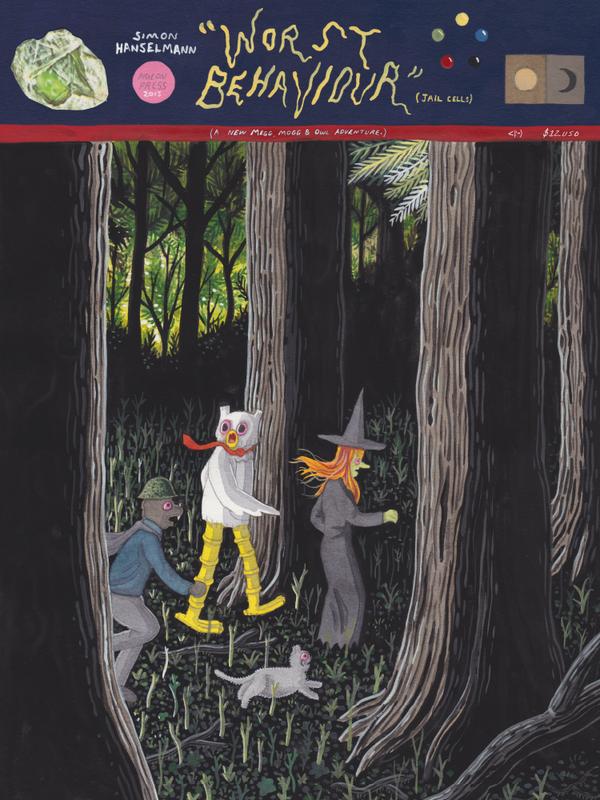

A proposito di novità editoriali, diventa sempre più ricca (ed è anche parziale, dato che mancano gran parte dei mini-comics) la lista dei fumetti che debutteranno al Toronto Comic Arts Festival del 9 e 10 maggio. Tra questi Worst Behaviour di Simon Hanselmann, una nuova avventura di circa 50 pagine di Megg, Mogg e Owl, in uscita per la Pigeon Press di Alvin Buenaventura, già editore di In the Garden of Evil di Burns e Killoffer. Intanto Fantagraphics annuncia per l’autunno il seguito del fortunato Megahex. Il nuovo volume si intitola Megg & Mogg in Amsterdam e raccoglie le storie pubblicate su Vice.com. Hanselmann ha parlato di recente dei suoi progetti futuri e del suo processo creativo in un’intervista al magazine Darling Sleeper.

Rimanendo in tema, arrivano finalmente sul canale You Tube della Small Press Expo i video dell’edizione 2014 del festival statunitense, tra cui potete trovare anche quello che riproduce il divertente incontro con Hanselmann, Michael DeForge e Patrick Kyle. Tra gli altri vi segnalo quello con Charles Burns, che parla della sua infanzia e legge alcuni passaggi da Sugar Skull, di prossima uscita per Rizzoli Lizard.

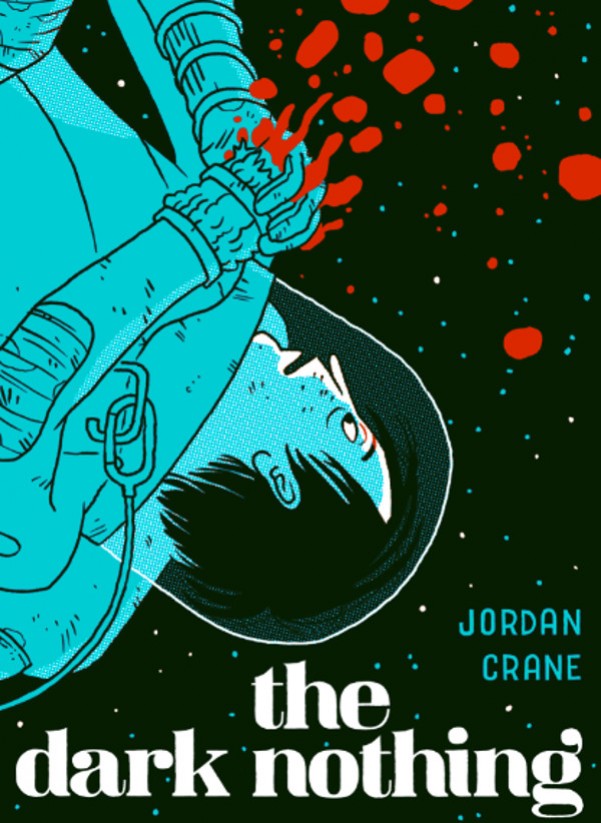

Il nuovo fumetto di Jordan Crane si intitola The Dark Nothing e sarà pubblicato in un’edizione limitata di 200 copie. La storia verrà poi ristampata, in una versione leggermente diversa, sul quinto e voluminoso numero di Uptight, in uscita per Fantagraphics. Per chi non conoscesse Crane, sul sito What Things Do potete leggere alcuni dei suoi fumetti.

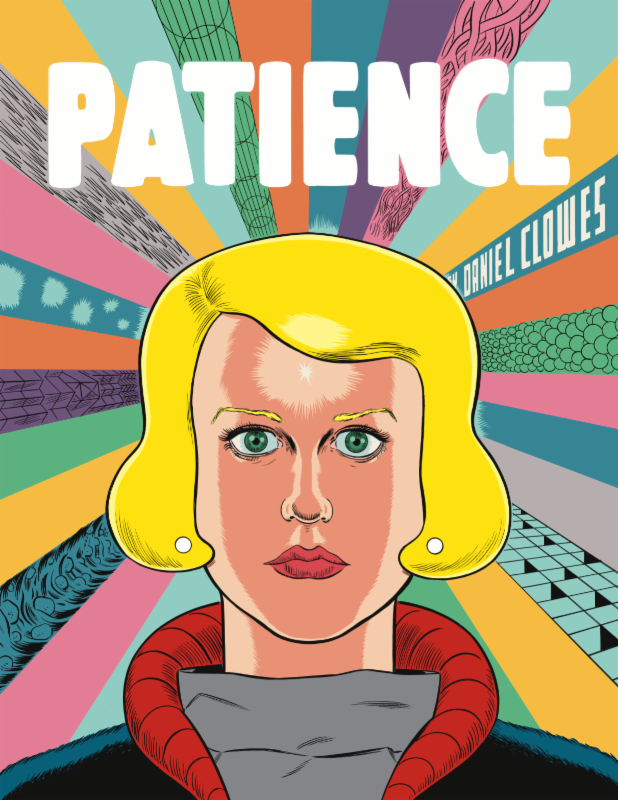

Nel post su Daniel Clowes di qualche giorno fa, dicevo che la scritta “Patience” diffusa come prima immagine del suo nuovo fumetto, in uscita a marzo 2016, sembrava più un invito ai lettori che il titolo del libro. E invece il titolo di questa storia di 180 pagine che avrà come tema il viaggio nel tempo sarà proprio Patience, come ha anticipato lo stesso autore in questa intervista al New York Times. Ieri è arrivato anche l’annuncio ufficiale di Fantagraphics, che ha definito Patience “an indescribable psychedelic science-fiction love story”. Intanto l’autore continua a rilasciare interviste, tra cui vi segnalo quella realizzata da Ray Pride per il sito Newcity Lit, che si differenzia dalle altre dato che verte sul rapporto tra l’autore e la sua città di origine, Chicago.

Il sito internet Broken Frontier ha lanciato una campagna Kickstarter per la pubblicazione di una lussuosa antologia di 250 pagine a colori, in formato gigante e copertina rigida. Oltre 40 gli artisti coinvolti, dagli stili più disparati. Tra questi Noah Van Sciver, autore di una storia di 10 pagine su un clown con problemi di rabbia che diventa schiavo degli uomini talpa.

Lo stesso Van Sciver è uno degli autori chiamati da Vice a rileggere i Blobby Boys di Alex Schubert. Tra gli altri Ron Regé Jr., Antoine Cossé, Hellen Jo.

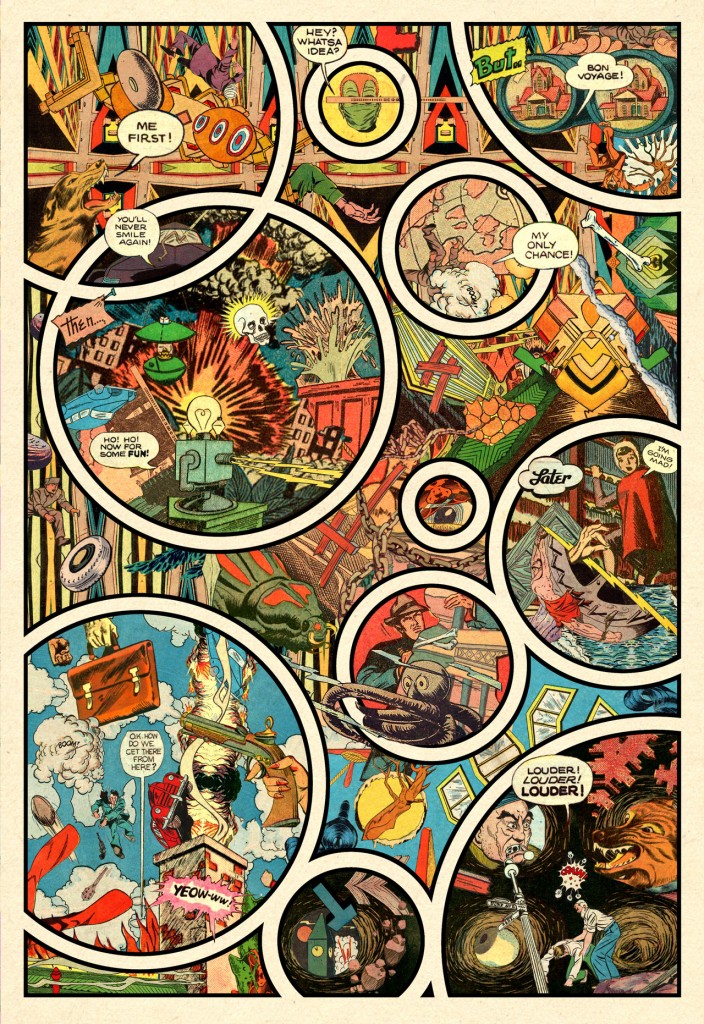

Un Tumblr assolutamente da vedere è quello di Samplerman, di cui potete ammirare un’immagine qui sotto. Per approfondire vi rimando all’intervista su It’s Nice That.

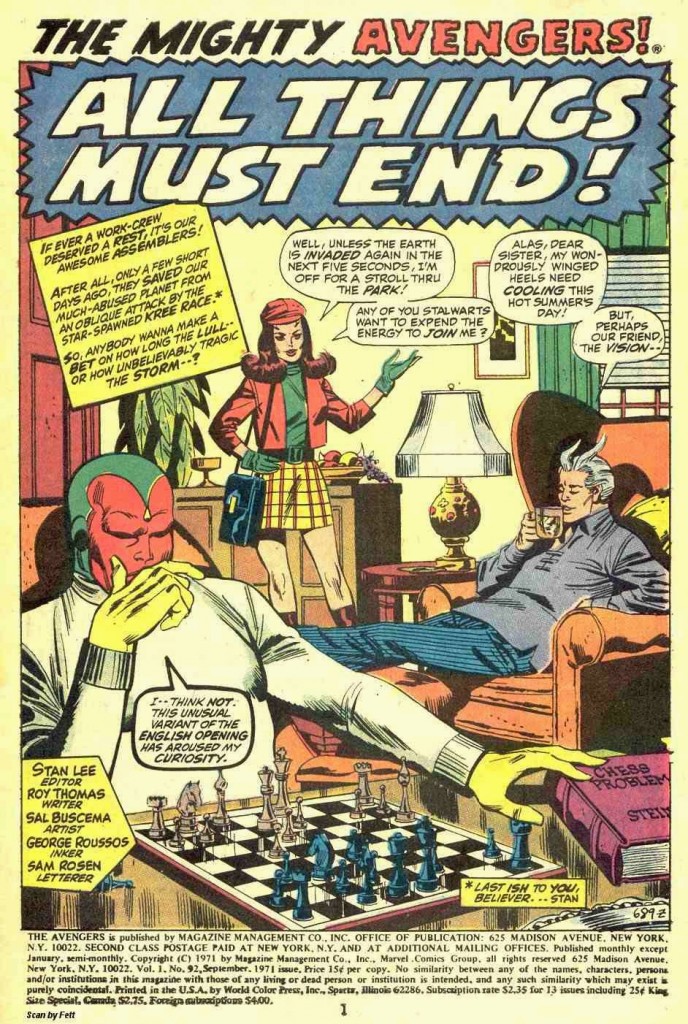

Con l’uscita di Avengers: Age of Ultron, fioccano articoli, immagini e quant’altro in qualche modo legati ai contenuti del film. Una delle proposte migliori è del sempre interessante blog Diversion of the Groovy Kind, che porta con orgoglio il sottotitolo “1970’s Comic Books Nostalgia”. Sembrerà fuori tono su un sito che si chiama Just Indie Comics, ma non posso fare a meno di consigliarvi questa sequenza di splash page con protagonisti Scarlet, Quicksilver e Visione a firma John e Sal Buscema, Don Heck, Barry Windsor-Smith, Rich Buckler, John Byrne e altri ancora.

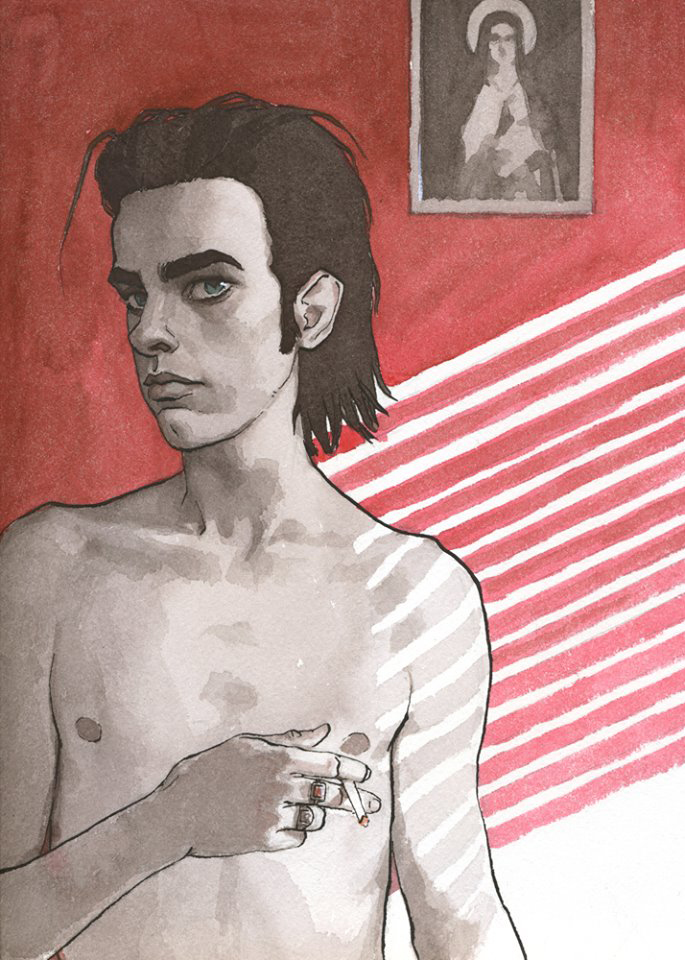

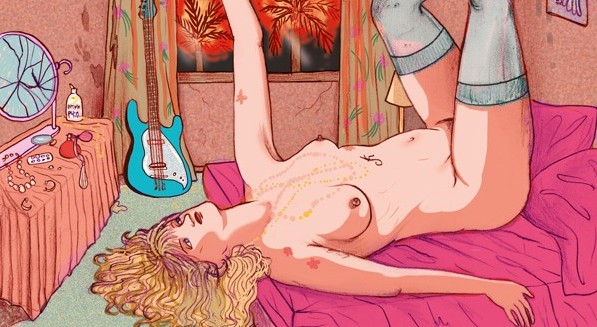

Le notti del Rock Motel

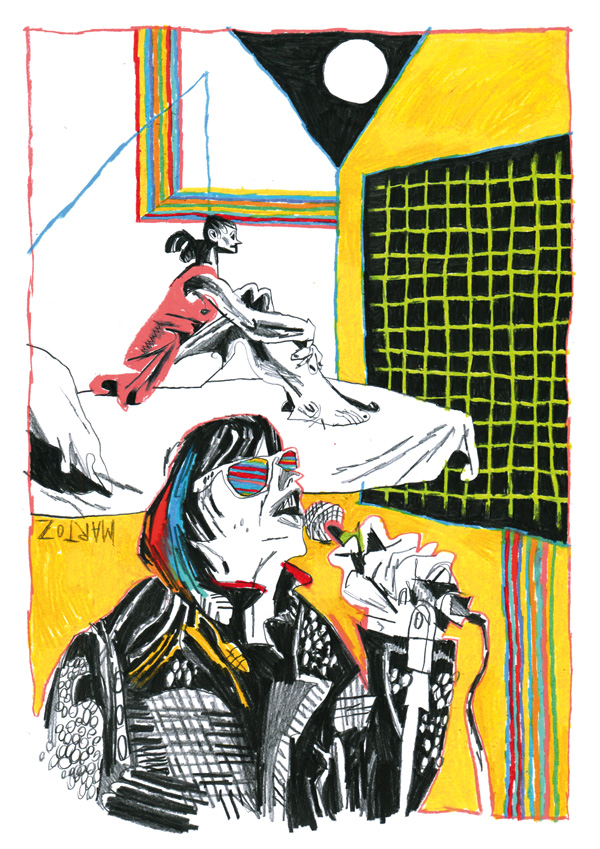

Dopo l’art book 64 Kamasutra, l’associazione culturale Squame torna con un nuovo libro illustrato da oltre 60 giovani artisti internazionali. Il tema questa volta è rappresentato dalle stanze di motel delle rock star, ricostruite a partire dall’immaginario artistico ed estetico dei musicisti, come potete ben vedere dal disegno di apertura, una Courtney Love colta in un momento di relax da Cristina Portolano. Rock Motel uscirà a giugno ma la campagna di crowdfunding è in corso soltanto fino al 15 maggio su Ulule. Il pacchetto base, che include libro di 144 pagine e tre cartoline, costa 17 euro ma si può sostenere la campagna anche con soli 5 euro. Con cifre più sostanziose si avrà diritto ad accessori, gadget e oggetti da collezione, come un vinile illustrato. Tanti i nomi coinvolti, tra cui cito brevemente Manuele Fior, Giacomo Nanni, Marino Neri, Anna Deflorian, Alessandro Ripane. La direzione artistica è come sempre di Francesca Protopapa, fondatrice della fanzine Squame, mentre la consulenza musicale è di Luc Frelon, dj e cultore del vinile.

Per approfondire i dettagli del crowdfunding e contribuire alla pubblicazione del volume potete andare qui. Per sbirciare nel Rock Motel e leggere le interviste agli artisti vi rimando al Tumblr del progetto. A seguire alcune illustrazioni in anteprima. Buona visione e… buon ascolto.

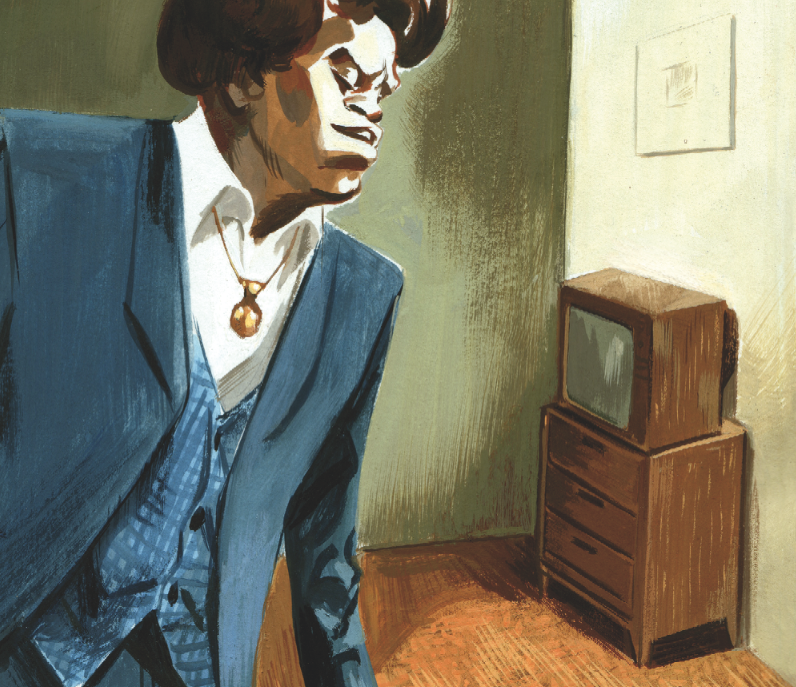

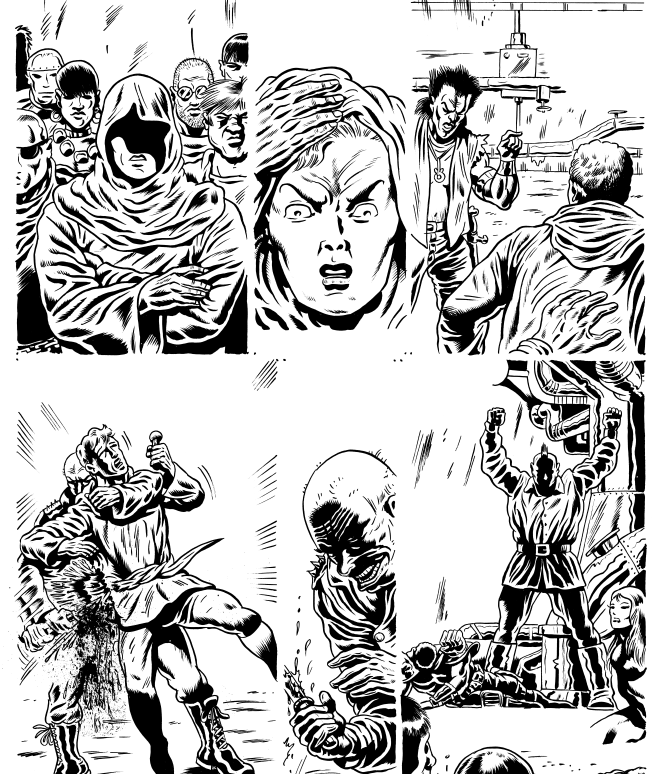

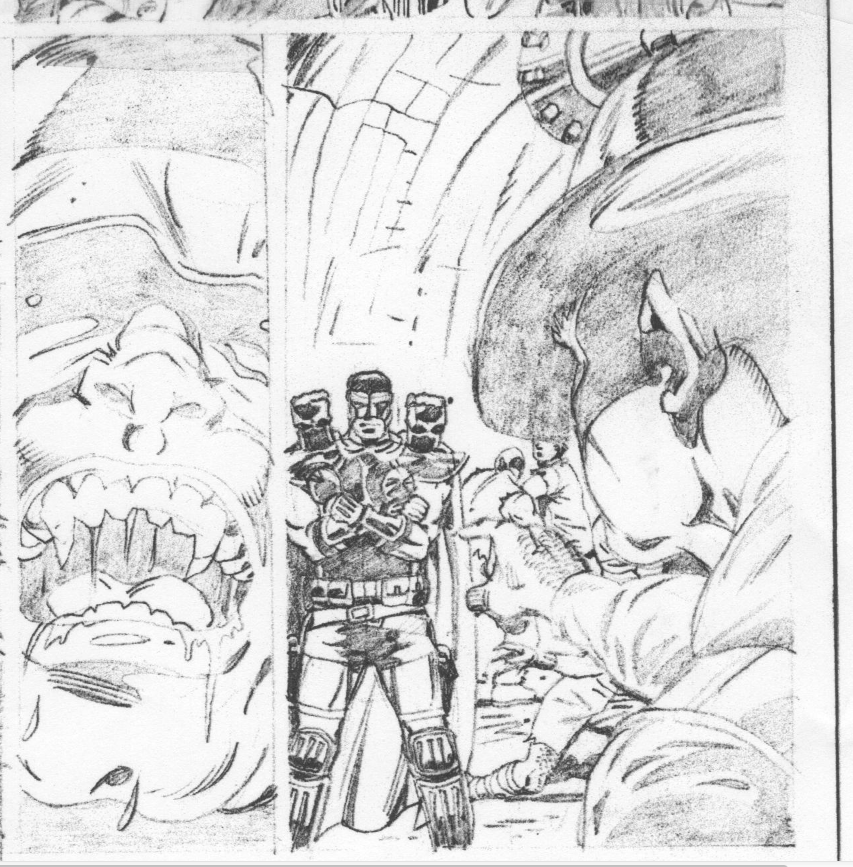

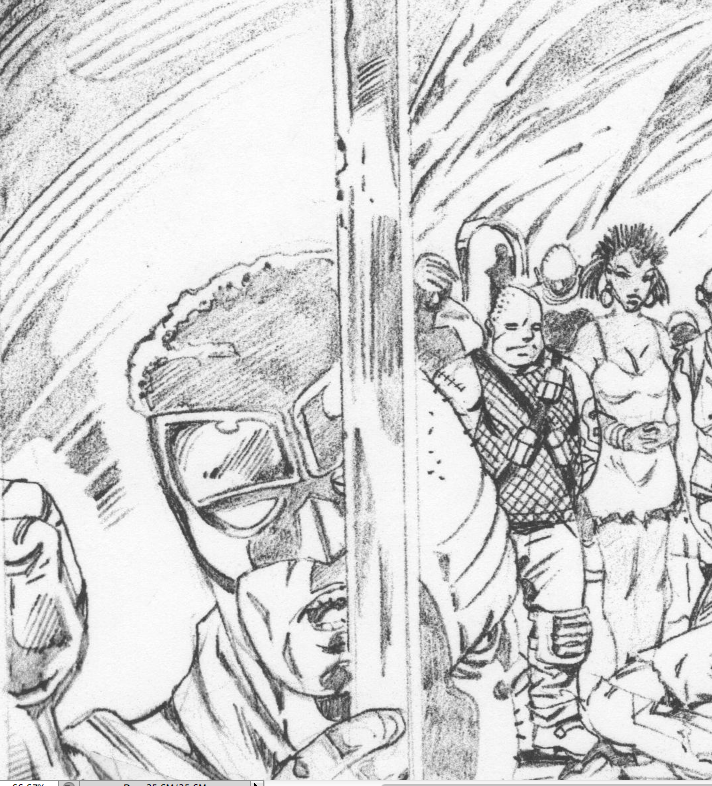

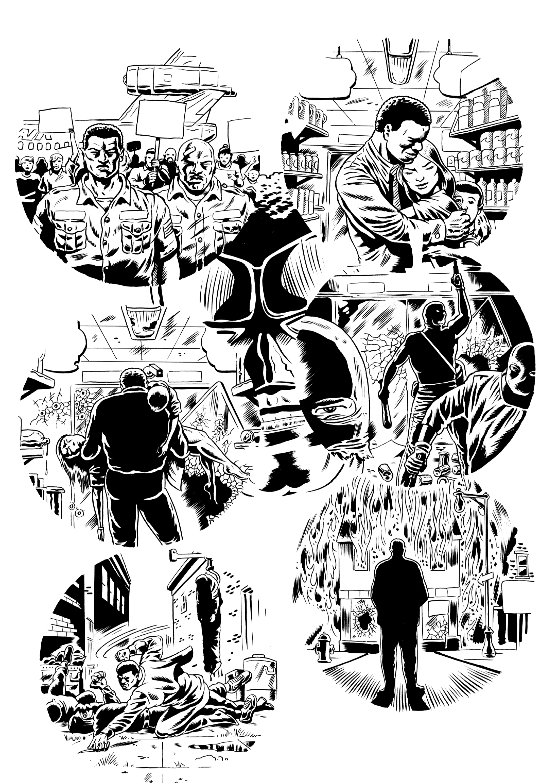

L’ultimo lavoro del grande Herb Trimpe

Herb Trimpe è stato uno dei disegnatori più importanti della Marvel degli anni ’70, famoso soprattutto per la sua lunga run su The Incredible Hulk. Trimpe ci ha lasciato lo scorso 13 aprile, mentre stava ultimando le matite di una storia per una nuova linea di fumetti chiamata All Time Comics, ideata dal newyorkese Josh Bayer, editor dell’antologia autoprodotta Suspect Device e autore di fumetti underground come Raw Power e Theth. Bayer è un grande fan dei fumetti Marvel di trenta o quaranta anni fa e ha ideato tra le altre cose numerosi bootleg di Rom, personaggio che in Italia ben conosciamo per la sua pubblicazione sulla storica antologia All American Comics edita dalla Comic Art. Le sue storie con protagonisti i cartoonist del Marvel Bullpen sono state spesso un’occasione per farci vedere l’uomo dietro l’artista, oltreché per denunciare il modus operandi della Marvel nei confronti di autori come Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko e Steve Gerber. Alcune scene dei suoi fumetti vedono Steve Ditko urlare “La Marvel e la Disney… sono il governo!” e una ragazza circondata da Deathlok, U.S. Agent, Howard The Duck e altri personaggi Marvel minori che dice “Facciamocene una ragione, qui siamo superflue come i disegnatori, gli inchiostratori e gli scrittori che hanno dato vita all’industria della Marvel Comics”.

Bayer di recente ha ricordato così Herb Trimpe sulla sua pagina Tumblr:

“L’anno scorso ho contattato Herb Trimpe e gli ho chiesto di disegnare una storia per una linea di fumetti che sto scrivendo ed editando. Eravamo in grado di offrirgli una tariffa decente e incredibilmente ha detto di sì, così che tra qualche mese pubblicherò quello che, a quanto ne so, è il suo ultimo fumetto. Il lavoro di Trimpe era dappertutto quando ero ragazzo, nei comic-book che uscivano e nelle ristampe, e i suoi personaggi fumettosi, spavaldi, monolitici, fluidi ma anche un po’ traballanti rappresentavano in pieno quella che era la mia idea di fumetto. […] Mentre mi arrivavano le mail con i suoi disegni l’anno scorso, ero rincuorato che a settant’anni stesse facendo uno dei suoi migliori lavori di sempre, pieno dei passaggi, delle luci e dello storytelling per cui era conosciuto. “Te lo devo dire, me la sto spassando… Era da parecchio tempo a questa parte che non facevo qualcosa di così divertente”, mi ha scritto, e io ne ero felicissimo. Ero contento per giorni ogni volta che lo sentivo. Continuavo a guardare il suo lavoro. Le linee erano sicure e potenti, il suo storytelling era ricco di quel tipo di inventiva che è il risultato delle migliaia e migliaia di pagine che aveva disegnato prima che entrassimo in contatto. Per me, avere l’approvazione sua o di altri professionisti come Rick Parker e Al Milgrom, ha significato avere tutto ciò che volevo dai fumetti, un cerchio senza fine tra passato e futuro. Soltanto in un’industria strana come questa qualcuno nella mia posizione, al livello più basso della piramide, può coinvolgere in un suo progetto artisti con anni e anni di esperienza e riconoscimenti alle spalle”.

Per il testo completo vi rimando alla versione inglese di questo post. Tutte le immagini sono tratte da Crime Destroyer Giant Size di Josh Bayer, Herb Trimpe e Benjamin Marra, in uscita a ottobre 2015.

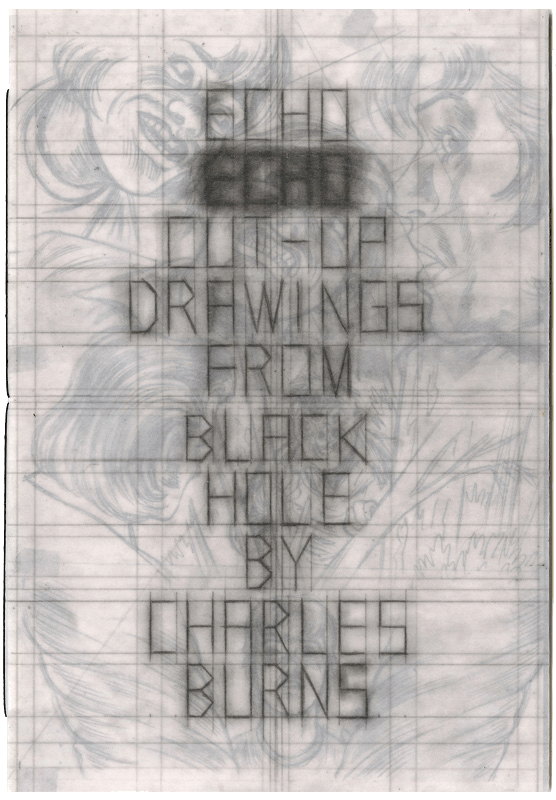

Una serata con Charles Burns

Giovedì 19 marzo la Libreria Giufà di Roma ha ospitato un incontro con Charles Burns, cartoonist statunitense che non ha bisogno di presentazioni. Burns, che i più conosceranno per la serie Black Hole, è arrivato a Roma per accompagnare la moglie Susan Moore, artista e insegnante di pittura, proprio come successe negli anni Ottanta, quando la coppia passò un paio di anni in Italia e Burns si unì al gruppo Valvoline. Più che un amarcord, la serata è stata l’occasione per far conoscere l’artista al pubblico romano, approfondendo il suo processo creativo e i temi dei suoi fumetti. A condurre la chiacchierata lo scrittore Francesco Pacifico, che fungeva anche da traduttore, mentre a occuparsi delle domande e delle digressioni sull’arte di Burns erano il critico di fumetti ed editor di Castelvecchi Alessio Trabacchini e il ben noto fumettista italiano Ratigher. Alla fine dell’incontro Burns si è trattenuto per ore a parlare con i lettori firmando dediche e soprattutto disegnando sketch, mostrando una disponibilità e una cordialità esemplari.

Alessio Trabacchini: Charles Burns è importante perché è un autore che sa raccontare la complessità. Ha trovato una forma narrativa e un segno per raccontare le ambivalenze, dei sentimenti, delle cose, del mondo. Vorrei chiedergli come è riuscito a raccontare un aspetto che nei fumetti è molto difficile da rendere, che è quello relativo al sesso, alla sessualità, alla bellezza e al desiderio. Penso che qui quasi tutti conosciamo le opere di Burns e lo associamo a qualcosa di molto estremo, o all’abiezione o a qualcosa di perverso: è vero a metà, perché in realtà Burns ha saputo raccontare benissimo la parte migliore dei sentimenti. Nelle opere di Burns e in particolare in Black Hole ci sono alcune delle rappresentazioni migliori del sesso che si possono trovare nei fumetti. E quindi vorrei domandargli qual è il suo approccio a questo aspetto della vita umana e alla sua rappresentazione.

Charles Burns: Quando sono riuscito a sentirmi a mio agio nell’esprimere qualcosa di veramente personale, ho voluto farlo cercando di essere il più possibile libero e aperto. La sessualità è nella vita di tutti, ma io non volevo fare qualcosa di totalmente gratuito o pornografico. Volevo che il sesso fosse una parte naturale della storia. In Black Hole per esempio ci sono delle scene molto forti ma la storia nel complesso non è gratuita, non è fatta per provocare o titillare il lettore. Mi piace l’idea di mettere in una storia di tre-quattrocento pagine dieci pagine focalizzate su qualcosa di molto forte, ma non di più. Ci sono stati dei momenti, mentre scrivevo, in cui pensavo “non so se la gente vuole vedere questo”. Pensavo che la mia visione delle cose fosse troppo cupa ma volevo allo stesso tempo essere più onesto e aperto possibile. All’inizio non ne ero molto consapevole, ma nelle mie prime opere mi sono abbastanza censurato, avevo delle idee che erano molto forti e forse disturbanti ma mi trattenevo dall’esprimerle. Ho cercato in tutti i modi di superare quel blocco, di fare qualcosa di forte e onesto… Comunque non ho mai incontrato una donna con la coda…

Ratigher: La mia prima domanda è simile ma su un altro aspetto. Io considero Burns il fumettista che più ha saputo raccontare l’occulto, il bizzarro. Se nel cinema c’è Lynch, nel fumetto c’è Burns, sono loro i custodi del mistero, dell’incubo, di tutto un mondo onirico e oscuro. Io immagino che lui abbia iniziato perché era attratto probabilmente dalle storiacce, dalle situazioni malsane, però visto il livello che ha raggiunto gli voglio chiedere se c’è stata una sorta di evoluzione tipo quella dei giochi di ruolo, cioè se da occultista, da amante delle cose bizzarre e oscure, senta di avere il potere di uno stregone, di poter far paura alle persone, di poter fare dei libri che abbiano delle forze oscure dentro.

Burns: Per qualche ragione le mie storie si muovono verso l’oscurità, ma io non voglio spaventare intenzionalmente qualcuno. Sin da piccolo sono stato attratto da un lato oscuro dell’America, un lato nascosto della cultura americana. C’è una facciata in cui tutto sembra a posto, ma sotto a questa c’è a volte un lato oscuro e nascosto. Sono stato sempre interessato a questa facciata e a ciò che rappresenta. Ed ero interessato anche alla realtà, la realtà in cui sono cresciuto, la realtà che sentivo mia e che non aveva niente a che fare con lo status quo e con la visione normale di una famiglia sicura e felice. Nessuna delle mie storie è molto felice.

Trabacchini: Un’altra cosa che volevo chiedere riguardava la linea. Ovviamente questo c’entra con il modo di raccontare che dicevo prima, perché per un autore di fumetti la prima scelta di stile per decidere come vuole raccontare è decidere il tipo di segno che utilizzerà. Il segno di Burns che conosciamo è netto, molto netto, con contrasti molto forti di bianco e nero, lo è diventato sempre di più nel corso degli anni ma era già abbastanza definito sin dall’inizio. Nonostante ci siano le ombre, questa è in qualche maniera una sua versione della linea chiara francese, un richiamo che nell’ultima trilogia diventa esplicito, perché c’è un mondo onirico in questi tre libri che è una sorta di mash-up fra la Tangeri di William Burroughs e Il Cairo che Hergé racconta ne Il granchio d’oro come scenario delle avventure di Tin Tin. Stavo riguardando poi questa cosa qua (mostra Echo Echo, una raccolta degli schizzi preliminari di Black Hole, ndr), che è interessante perché si capisce qual è il modo di arrivare alla linea chiara, cioè a partire da disegni che sono comunque un groviglio di segni, di incroci di linee, dove tutto è molto forte, molto istintivo, e questi disegni diventano quel segno di Black Hole che è così controllato da rimanere coerente, omogeneo per un’opera che è durata dieci anni. In realtà guardando le matite di Tin Tin sono molto simili, sono piene di segni, di linee incrociate, per arrivare a qualcosa di chiaro e preciso. E quindi è così che penso che la linea riesce a trattenere tante inquietudini, tante tensioni. Mi piacerebbe che ci parlasse di come si arriva a quel segno.

Burns: Credo che lo stile del mio lavoro emuli lo stile americano degli anni Cinquanta e Sessanta. Sin dall’inizio mi sono ispirato a Harvey Kurtzman, a Mad Magazine e a quelle meravigliose linee molto scure che si vedevano all’epoca. D’altro canto mi piacevano le splendide linee chiare di Hergé, il che è piuttosto insolito per un americano della mia generazione. Comunque rispetto alla linea chiara francese, il mio stile è più per una linea scura e spessa ottenuta con l’uso del pennello. Mi è stato fatto notare che anche Hergé quando disegnava aveva una linea molto grezza, molto aperta, che poi veniva distillata e distillata fino a diventare questa linea più specifica. Il libro che hai mostrato è una collezione di disegni preliminari, alcuni sono più puliti, altri più grezzi, molto gestuali. Partono da un’idea molto legata al gesto di disegnare e poi si raffinano via via che lavoro.

Ratigher: Anche io rimango su una domanda tecnica, ma che poi tecnica non sarà. Da fumettista in erba la cosa del lavoro di Burns che mi ha cambiato il modo di vedere i fumetti è stato il fatto che il suo disegno molto tecnico, che piace tanto e lo fa amare da un gran numero di persone, sia sempre un disegno in ogni vignetta narrativo. Anche nelle illustrazioni, quando disegna il volto di una persona, tu ti immagini la vita di quella persona, non è mai un disegno fermo e non è mai un disegno fatto per dare sfoggio della sua tecnica. Ogni pagina è molto studiata, con i bianchi e i neri perfetti, però ogni vignetta racconta sempre un pezzo di storia, non c’è un piacere fine a se stesso nel disegno. Quindi volevo chiedere se questa cosa è vera, se lo rispecchia e come ci ha lavorato.

Ratigher: Anche io rimango su una domanda tecnica, ma che poi tecnica non sarà. Da fumettista in erba la cosa del lavoro di Burns che mi ha cambiato il modo di vedere i fumetti è stato il fatto che il suo disegno molto tecnico, che piace tanto e lo fa amare da un gran numero di persone, sia sempre un disegno in ogni vignetta narrativo. Anche nelle illustrazioni, quando disegna il volto di una persona, tu ti immagini la vita di quella persona, non è mai un disegno fermo e non è mai un disegno fatto per dare sfoggio della sua tecnica. Ogni pagina è molto studiata, con i bianchi e i neri perfetti, però ogni vignetta racconta sempre un pezzo di storia, non c’è un piacere fine a se stesso nel disegno. Quindi volevo chiedere se questa cosa è vera, se lo rispecchia e come ci ha lavorato.

Burns: Per me il fumetto è tutto incentrato sulla storia. So che la gente guarda il mio lavoro e dice “guarda questa linea”, “guarda quanto è bravo a disegnare”, ma dal mio punto di vista la storia è sempre l’elemento più importante. Raccontare la storia è un processo di distillazione continua, si inizia da una bozza e poi le idee e il lavoro vengono pian piano rifiniti. Ci sono momenti in cui voglio disegnare una bella immagine, ma se non è parte della storia non ci entra.

Ratigher: Ma è una cosa innata? Perché vista da fuori, ogni vignetta è disegnata in maniera eccelsa, però continua a essere narrativa, anche nelle sue storie vecchie. Voglio sapere se lui ci ha ragionato, perché l’alchimia è quasi solo sua, qui ci sono un sacco di lettori di fumetti e chiedo anche a loro se ci sono disegnatori così tecnici e al tempo stesso narrativi, a me viene in mente tra i grandi americani soltanto Robert Crumb, che ha un controllo del disegno sempre bello, sempre ricco ma sempre devoto alla storia. Quindi voglio sapere se per lui è stato uno sforzo oppure se ha culo e gli è venuto da quando è nato.

Burns: Io sono nato con… niente (in italiano, ndr). Credo che si siano dei cartoonist che partono da un aspetto visuale e altri che partono dall’aspetto letterario. Io ho cominciato dall’aspetto visuale e poi ho dovuto insegnare a me stesso il linguaggio dei fumetti per poter raccontare una storia. Quest’anno compirò sessant’anni e non ho ancora ben capito come si fa, ma comunque ci provo. Quando le parole e le immagini si combinano perfettamente, le immagini diventano invisibili. Il lettore si trova nel mondo della storia e non pensa più alla tecnica con cui è stata realizzata, non pensa “oh, che splendido disegno”… E’ immerso. E’ la stessa cosa che succede con i bei film o con i bei romanzi, con qualsiasi cosa. La tecnica diventa invisibile.

Pacifico: A questo punto ti chiedo se puoi darci degli esempi di film e romanzi in cui la tecnica è diventata invisibile. A me per esempio viene in mente l’ultimo film di Paul Thomas Anderson, Inherent Vice, in cui sembra che lui abbia cercato di proposito di cancellare tutta l’idea di un regista che fa le grandi scene per farci sentire solo la storia.

Burns: Per me è sempre impossibile indicare con precisione le cose che mi hanno influenzato. Potrei citare dei fumetti in particolare di cui mi piacciono la tecnica, la linea, l’aspetto, ma in realtà sono stato influenzato un po’ da tutto. Io cerco di fare del mio meglio per raccontare la mia storia, non la storia di Ernest Hemingway o di Nabokov o di Murakami.

Ratigher: Quello che volevo sapere io, riallacciandomi alla domanda di prima, è sapere se Burns a volte si siede e fa un disegno che non sia un fumetto, che non sia narrativo. Se gli capita mai che magari gli piace un fiore e decide di disegnarlo.

Burns: Mi piacerebbe farlo, ma no. Sfortunatamente il mio è un processo lentissimo. Per esempio, il mio amico Chris Ware mi ha raccontato che lui ha questo grande foglio di carta bianca, si mette seduto e inizia a disegnare. Questo per me è impossibile, io ho appunti su appunti e foglietti con piccoli disegni, schizzi, bozze. Il mio processo non è assolutamente naturale, è lento ed elaborato. Penso che la mia vita sarebbe molto più semplice se avessi un approccio più diretto ma non è possibile.

Valerio Bindi (fumettista italiano e curatore del Crack! Festival): Stavo già accennando prima a Burns quello che penso del suo lavoro, cioè che lui è profondo nella struttura della storia, che ha sempre molti livelli – il richiamo agli anni Cinquanta e Sessanta, l’adolescenza, il bosco, le metafore, i luoghi oscuri – e poi è invece quasi superficiale nel disegno e questa superficialità dà a questo mondo uno sguardo molto ampio. C’era questa riflessione che faceva Deleuze su Lewis Carroll, in cui diceva che Lewis Carroll è ampio e non è profondo. Burns usa tutte e due le armi e in questo modo ha un segno molto affascinante. Per la mia generazione lui non è il disegnatore dell’inquieto e dell’oscuro ma il disegnatore che ha portato le tematiche anni Cinquanta verso il mondo dell’underground. Io e il mio gruppo di disegnatori che negli anni Novanta cominciavano a fare fumetti, come il Professor Bad Trip, trovavamo in lui una rilettura dei racconti dell’underground in una chiave fredda, sintetica e chiara che era proprio il nostro sentire degli anni Ottanta e Novanta. Adesso però mi sembra che l’underground si sia spostato, mi sembra che il movimento dell’underground nel fumetto in questo momento parli europeo, mi sembra che l’America sia in qualche modo seguendo le nostre cose. Volevo sapere che cosa ne pensa lui, se vede un underground oggi e se sì dove lo vede.

Burns: L’undergound per me significava avere tredici-quattordici anni e scoprire Robert Crumb e i fumetti che guardavano oltre il mondo commerciale, in cui gli autori cercavano di esprimere se stessi. All’inizio i fumetti underground dovevano essere per forza trasgressivi, perché essere underground voleva dire occuparsi di sesso, droga, politica. Adesso è diverso, perché ormai è dato per scontato che chiunque può scrivere qualcosa di veramente personale senza doversi preoccupare di appartenere a un genere predefinito… Non so se il mondo dei fumetti underground è mai esistito realmente. L’underground sembra un qualcosa di difficilmente accessibile, ma da ragazzino mi bastava semplicemente salire su un autobus e andare in un negozio per comprare Zap, i fumetti di Crumb o qualsiasi fumetto hippy e più tardi punk. Mi piace l’idea che qualche ventenne non sappia chi è Robert Crumb o chi sono io e che guardi a qualcosa di nuovo, muovendosi in altre direzioni. Non c’è nessun bisogno di conoscere i classici. Non sono interessato ai giovani artisti che citano continuamente le loro influenze. E’ un piacere quando le cose vanno avanti, progrediscono. Anni fa ricordo che il mio caro amico Art Spiegelman mi disse che noi dovevamo superare Will Eisner, guardare oltre. L’underground è un ragazzo di diciassette, diciotto, diciannove o anche vent’anni che non ha mai sentito parlare di me.